Particularly in the Tarnopol Region

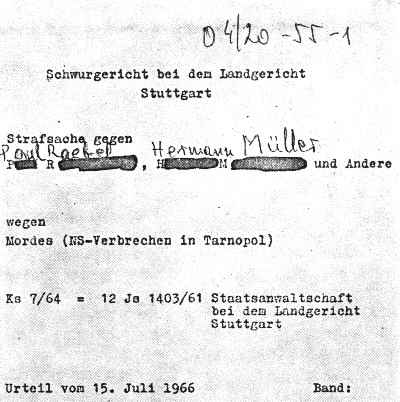

A Segment of the Verdict Against Roebel and Müller

1. First Wave of Extermination

1 In the fall of 1941, the first wave of extermination of the Jews of Tarnopol took place. It was considered relatively light compared to the later waves.

Many Jews were arbitrarily shot to death next to graves prepared in advance, at the command of the KdS and carried out by the men of the Department of Deportation.

The winter of 1941–42 constituted a kind of calm period in which crimes took place mostly against Jewish properties, and not against the Jews themselves. The arbitrary mass murders still did not arouse any suspicions by the Jews of the area concerning a complete genocide against Galician Jewry. Jews were required to hand over all money and precious metals, along with all furs that were in their possession. This came to be known as the ‘Aktion of Fur’ during December 1941. Anyone who refused or attempted to evade this demand was in mortal danger.

2. Second Wave of Extermination

2a. The strike against the Jewish population in Spring, 1942, revealed the methodology for the first time. That occurred when the Belzec extermination camp, in the zone of the conquest of Galicia, was built for the purpose of the mass murder of thousands of Jewish victims. The Germans then moved ahead with the wave of Aktions that inundated the entire region, and slowed only for a brief time through the summer of 1942.

The sign of recognition, in those early Aktions, was the categorization of the victims. Cases of the indigent, elderly, sick, and orphaned, those lacking social backing and lacking value as members of a labor force, were liquidated in the first blow. The Committee of the Community, the Judenrat, was responsible for arranging lists with the names of these victims for the Germans.

The huge number of victims from the city of Lemberg alone, at the time of the Nazi invasion, was about 160,000 Jews. These victims activated the extermination machine at Belzec in a full reception and tempo that made it impossible for the camp to absorb transports of victims from other districts. As a result, extermination and mass killing was perpetrated in those other places by shooting.

[Page 140]

2b. The Aktions in the Tarnopol region were always carried out using the same method. First, they harnessed the Jewish Committees of the Community to draw up lists of names of the victims. Later, when the objectives of the Aktions and their outcomes became clear to everyone and the Jewish population refused to obey, they refused the appeals of the Communal Committee to present themselves at the assembly places. Then the gathering of the victims at the assembly points was accomplished with a cruelty and barbarity that cannot be described.

Equipped with weapons, curses, and whips, the Extermination Services, with the accompaniment of Jewish police, Ukrainian lawmen, German soldiers and Gendarmerie, burst into the houses of the victims and forced them, with cruel blows and shots, to hurry to the gathering places. There, they were ordered to bend to their knees or to crouch on the ground, in their underwear only, for hours or even days, without moving a limb. Then they were taken to shooting places that were euphemistically called, by the S.S., ‘Immigration Points,’ places where mass graves had been dug for the victims in advance. These were dug by men of the Construction Service, which consisted of Ukrainian and Polish staffs, similar to the German Construction Service, which operated in the boundaries of the Reich. The Shooting Commandos, firing squads, mostly composed of men from the Deportation Department of Tarnopol, were located near the mass grave excavations.

|

|

[Page 141]

In exceptional cases, security forces were added, such as policemen, gendarmerie, and Ukrainian militia, which generally served only for guard purposes, and also as Shooting Commandos, even though, with regard to them, different instructions existed.

Under guard, they ordered the victims to form groups, about 30 to 50 meters from the open graves, and to wait in place. In this way, they did not withhold from them the terrifying and protracted scene of mass execution ahead of them until their turn came. They were sent in small groups to the edge of the graves, while opposite them riflemen were positioned according to the number of victims. There was no resistance. Isolated individuals, who dared to try to escape, were killed on the spot by these murderers.

Before their last steps to the edge of the open graves, the victims were ordered to strip completely. In 1943, this was certainly the procedure. It is possible that, even before that, this is how the Germans customarily operated. Then the victims were told to face the corpses already in the graves, and to stand in front of ‘their’ riflemen. At a signal, the riflemen shot into the skulls of their victims and, with a swift kick, threw them into the mass graves.

To victims who were a complete family, they allowed this last stand together. More mature children were ordered to step like adults to the edge of the graves. Infants were left in the arms of their mothers. The mother was shot first, and at the moment she buckled under, they aimed and shot the infant.

There were instances where the shots missed their target and sometimes it was possible to discern limbs moving or to hear groans. Seldom did they redeem such wounded with an additional shot. But, generally, those unfortunates suffocated under the next to be slain, or at the time of covering over the graves – something that was also carried out superficially.

Since the bodies of the victims swelled very much, and their graves usually lifted up a few meters – only later subsiding – it was possible to close the graves, finally, after only a few days.

The men of The Shooting Commandos were subjected to difficult psychological depression. The terrifying human suffering, which occurred before their eyes, was so awful that the internal callousness toward the Jews, which they had adopted for themselves, did not always hold up for them. In order to subdue any weakness or human bonding, and to ease forgetfulness, alcohol began to play a considerable role. The men of the Commandos were given alcoholic beverages to drink, liberally, before, during and after the executions. Toward the end of the Aktions, when most of the riflemen were absolutely drunk, the poorly aimed shots became more frequent, and the cruelty increased even more.

Already at the time of this focused Aktion against the Jews and, later, after the reduction of the Deportation Department, all of the Deportation Department men were tied to the goal of mass exterminations, unless they were mustered for another important activity.

Aside from the place of execution, only a negligible power in the Deportation Department remained. Usually, those were only three female typists.

Before the Aktion, in a choreographed manner, the Commander of the place would convene a session in which the details of carrying it out were decided. The commander of the place would receive his instructions from the KdS in Lemberg that, for its part, received instructions from the SSPF, or the governor of the District, who decided on the time and place of the Aktions and handed it over to the Deportation Department for carrying out.

[Page 142]

The instructions of the KdS, among others, established the staffing of those carrying out the activity, and also the evaluation of the number of victims that were, for the most part, minimal.

The function of the Commander of the Deportation Department, in coordination with the instructions of the KdS, was to execute the maximum number of Jews in the shortest amount of time. There is no evidence that, within the authority of the Commander of the Deportation Department in Tarnopol, there was ever the ability to determine, on his own, the number and place of the victims of the notorious Aktions.

If it happened that Aktions occurred at the very same time in several places, the Commander of the Deportation Department transferred his authority to his appointees, who substituted for him. He was sufficiently mobile and could arrive by automobile at any place he wished to follow up on personally, and with his own eyes, to observe how his subordinates had carried out the extermination orders. There were instances where he personally commanded the Aktions. He did not content himself with following from the side, but participated with his own hands as a rifleman at the mass graves. In doing so, he fulfilled instructions, which said that a Commander was to serve as an example to his subordinates.

3a. Arranging the matter of substituting for Jews who were vital as a labor force when reaching the third wave of extermination:

For the time being, with difficulty, HSSPF Krieger and SSPF Katzmann were able to agree to keep alive those few Jews who were especially valuable for the war economy, such as professionals in the military realm of the arms and weapons industry. For psychological reasons, their families were also temporarily left alive.

As far as they were concerned, the total extermination of the Jewish population, and its removal from the face of the earth, constituted the highest, most exalted command, more important than anything. In this idea, they were of one mindset with the head leadership.

Katzmann did everything to reduce to a minimum the number of Jewish workers in German workplaces and projects. He was alarmed and fought, not only against the contemptible broadmindedness of the civilian labor managers, but also against the frequent readiness of the management, and even the army, to comply with the requests of many Jewish workers, and with the excessive use of labor permits bestowing a certain security upon Jews.

Katzmann, in his appeal to the KdS Supreme Field Command 365, and the Armament Corp in Lemberg, wrote on November 6, 1942, “Concerning the speedy release of Jewish professionals from the labor process, as a supreme mandatory principle.” He demanded the immediate replacement of Jewish professionals with German ones for his projects and labor positions. He accused the German army of “encouraging Jewish parasitism through the issuance of special permits, without any inspections,” as is expressed in his report of June 30, 1943, directed to Krieger HSS.

With extremism and severity, he began personally arranging the replacement of Jewish professionals with Aryans, without encountering any further opposition at all. He reported about this, personally, as follows,

[Page 143]

“Since the management has proved its ineffectiveness and inability to overcome chaos, the matter of the replacement of the Jewish workforce has been transferred to the hands of the S.S. and the commanders of the police.”

The personal and energetic intervention of Katzmann, a sign of his power, possessed a sharp, decisive significance for the Jewish population. These labor permits were the only hope of remaining alive for their Jewish holders, since the Aktions of Spring 1942 left the unemployed Jews with deadly terror and fears.

In the city, in the district of Lemberg, tens of thousands of unemployed or semi–employed Jews were sent to the slaughter. Rumors about this terrible misfortune traveled terrifyingly around the expanses of the country, something that had the effect of making these permits even more coveted and sought after. Many Jews who were unable to obtain employment in German projects or labor jobs attempted to save their lives by forging permits. The matter was revealed in an inspection conducted by the police forces.

“In their thousands” – as Katzmann emphasizes in his report of June 30, 1943, holders of such forged labor permits were sent to ‘Special Handling,’ meaning, to execution. Now there was a probability that the SSPF men and their subordinates would closely scrutinize those individual vital Jews who remained, and separate them from the rest of the Jewish population. Those Jews who lacked utility and who were deprived of rights and protection, would surely be caught up in the mass wave of extermination, which was planned to be carried out during the second half of 1942.

3b. The Third Wave of Exterminations: Mass Extermination in Belzec

In the summer of 1942, the technical forecasts for the extermination of Galician Jewry were published. Already at any early stage, it was clear that with the existing conditions at Belzec, and even with additional help from Lemberg, they would not be up to the task.

The solitary bunk, which stood at their disposal at Belzec, and whose interior was made of tin, was capable of killing only about 150 people at a time with poison gas.

In June 1942 they erected, in place of this bunk, a massive stone building that contained six gas–chambers, with which it was possible to simultaneously gas about 1,500 people. From then on, the absorption of relatively large transports, which were liquidated within a few hours, was made feasible.

The seizure of the Jews, in great numbers, by the men of the Deportation Department of the Armed Security Forces wasn't a problem. The problem was transport. The distance from Tarnopol to Belzec was more than 200 kilometers. The main issue was that the network of railroad tracks of the East was in the middle of the battle area, which constituted an especially difficult problem.

[Page 144]

Himmler, with the help of his assistant, the S.S. Commander Wolf, sought the aid of the Reich Transport Ministry.

His appeals had results. He was promised a free field of action and, on July 19, 1942, he issued an order, in a letter to Krieger, the head of SSPF, that “the transfer of the entire Jewish population under the Administration will be carried out, and they will be liquidated by December 31, 1942. From that date forward, it will be forbidden for a person of Jewish origin to be found in the area, unless he will be found in one of the concentration camps in Warsaw, Krakow or Czestochowa, Radom or Lublin. One should abolish, by that date, all the positions which Jews are still holding, and only in instances in which there is no possibility to abolish a position, should one not transfer its Jewish holders to one of the concentration camps.”

This order was the basis of an extermination of tremendous dimensions, which swept over all of Galicia, and which continued from the beginning of July until the end of December 1942. This horrible wave left an especially small number of Jews in isolated ghettos only. Beginning July 22, 1942, ten thousand Jews per week were murdered in the Belzec extermination camp.

S.S. Commander Wolf, Personal Adjutant to Himmler, wrote a letter on July 28, 1942, on this subject to his colleague, Albert Ganzenmoller, the Under Secretary of State at the Reich Transport Ministry. Wolf wrote that in accordance with the agreement between the management of the Eastern Railroad and the security forces in Krakow that beginning July 22, 1942, a train with 5,000 Jews from Przemysl to Belzec would be instituted twice a week. A short time after, the railroad complex passed from Przemysl through Lemberg on its way to Belzec.

In an August 13, 1942 letter of thanks, Wolf also expressed the satisfaction of the S.S, “Fourteen days from now, from day to day, a train departs carrying 5,000 of the sons of the Chosen People to Treblinka and, with this, we have achieved the acceleration of the process of the transfer of this population. I have been in contact with those concerned with the matter and everything is being carried out without frictions and with maximal security.”

Those logistics concluded the need for the Shooting Commandos, and for a while the activities of the security forces changed. Now the emphasis was placed on packing the transports. The place and times of the Aktions were fixed in accordance with the timetable of the Eastern Railroad. Having established a fixed timetable for the transport trains, it became possible to carry out a number of Aktions at the very same time. The number of victims was determined according to the capacity of the transports.

3c. The Carrying out of the Aktions of Transports by the Deportation Department of Tarnopol

The first order, pertaining to the activities in the framework of the third wave of extermination, reached the Deportation Department in Tarnopol only at the end of August 1943. Until then, the Belzec camp, despite the expansion of its capability, was occupied because of the crowding together of transports from Lemberg and from other places in the region.

The Deportation Department was assigned to ship tremendous transports to Belzec from August 28 to the middle of November. These transports came, this time, from those places, which, because of technical difficulties, they had bypassed in the course of the previous Aktions.

[Page 145]

The transport activities were generally carried out in great haste. The reason for this was not a result of the large number of Aktions carried out within only a few months, and not even a result of the exacting inspection of labor permits, which were signed anew, and known as “The Aktion of the Seals.” Now such particulars were viewed as a waste of time. The principal reason for haste was due to the fact that the current Jewish population had begun to evade the claws of its murderers. The Jews began building countless hiding places to which they disappeared at the first signs of an Aktion. Ones who did not succeed in hiding, but instead lingered in their apartments for as long as possible until found, were forcibly taken to the places of assembly.

It became clear that the Germans had a difficult time gathering victims. Valuable time went to waste – especially in this period – as they were obliged to gather the majority of the Jewish population by the end of the year, packing the capacity of the transports to the maximum. Now the transports were carried out in sudden and energetic Aktions, which gradually became frequent and did not leave the Jews time to hide.

The gathering of the victims therefore became several times more terrifying. From then on, the soldiers of the Deportation Department and their helpers spurred on the terrified Jews with all their means, and with their full staffs, in order not to lose time. Jews now were forbidden the opportunity to take their clothes or any food at all to the places of assembly. Anyone who remained behind, whether he wished to continue to live, or whether he attempted to flee, or whether the reason was illness or old age, was ordered to be shot on the spot.

It became the job of the Committee of the Community, the Judenrat, to gather corpses from the houses and from the streets. At places of assembly, the victims were subjected to terrifying conditions. Lacking everything, they were exposed to awful psychological and physical suffering. For hours, and sometimes for days, they had to kneel or crouch on the ground without moving a limb. While they were subjected to this horrible crowding, they were left to the worst conditions of severe weather. Everyone knew that if he even moved a limb, he would risk lashes or being shot. In instances in which the victims were gathered into enclosed places, they would pack them in with shots until there was no possibility of sitting down.

In addition to the blows and gunshots was added the torture of withholding any food or water from the unfortunate ones, including women and children. The children were the ones who suffered most. When they later pushed the tired and dirty victims, after days of waiting under terrifying conditions, into the railroad cars, their suffering was made many times more severe. Without mercy, they packed the victims into the trains under a hail of blows and shots. It was impossible to sit or to lie down and the transport lasted an entire day. They threw the corpses of those killed into the cars, onto the heads of the victims, and then closed the doors upon them, crushing the limbs and the bodies of the last ones pressed in, without any consideration. They even closed over the especially narrow, few air holes in the train cars with nails. Sometimes, particularly in the burning heat of the severe month of August 1942, the foul condition in the cars caused a situation where most of the victims suffocated during the journey of terror.

The lack of air, the awful suffering before and during the passage, the lack of water or food, regularly caused numerous deaths, which enabled for the victims who remained alive

[Page 146]

a little more room. Sometimes, the corpses served as places to sit. Despite these barbarous terrors, the will to live was not extinguished, especially among the young people.

Though the shaky condition of the cars provided opportunities for escape, the only escape route that remained was jumping from a car during the journey. Very few succeeded. Many breathed their last breath either from being shot by the guards, falling under the wheels of the train, or from wounds that were inflicted on them in the leap from the cars.

Despite this, another opportunity became possible for a small number of men, those whom they had designated for the notorious Zwangsarbeitslager–ZAL–L (ZAL–Lemberg) a slave labor camp, which was on Janowska Street in Lemberg. It continued its operations after Belzec had been abandoned. For this, they were provided death by a different method. The Aktions, which were conducted on the Jews, left their awful imprint upon the non–Jewish residents of each place, even though they apparently knew very little of what occurred.

In the weekly and secret News of the District, which was edited by the Chief Department of Propaganda of the Administration in Krakow, the Germans attempted to allude cautiously to death camps and associated activities in front of the Governor. In the September 24, 1942 weekly report the following was described, “At this hour, Aktions of ‘Transfer’ against the Jews are being conducted, in all the areas of Galicia. On account of the great extent of the Aktions, it is impossible to totally hide these activities from the local population.”

On October 16, 1942, the following announcement in Lemberg was in the Weekly News:The good mood of the residents of the place was muted by the continuation of the conscription of the labor force for the Reich, and also because of the continued transport of Jews. The Aktions of those transports, which are being taken against the Jews, which do not align with the behavior of a cultural nation, surprisingly cause the comparison of these methods of the Gestapo to those of the G.P.U.

The conditions in transport trains are so terrifying that it is impossible to prevent the escape of Jews. As a result of these escapes, the hunt for the escapees is taking place, and cruel shootings echo in the transfer stations. Likewise, it is known that the corpses of Jews who were shot by the Germans are left for days in the streets. In spite of the fact that all the Germans in all expanses of the Reich, including the foreign populations, are convinced of the correctness of the liquidation of the Jews, perhaps it would be better if the matter would be carried out secretly without it arousing such great repugnance.”

This principal and basic extermination was supposed to leave alive, according to the intention of the management, only those Jewish forced laborers on the roads and in concentration camps, and exceptionally vital Jewish professionals for the weapons industry, or those who served the army and who underwent an especially exacting re–education. Temporarily, in accordance with the instructions of the management, members of the Committees of the Community, and policemen, or officials of the administration of the Jews, and members of their families were also left alive.

Unintentionally, and in opposition to the design of the murderers, some Jews were left alive who, for technical reasons, had not yet been located, or those who succeeded in hiding in the Ghetto itself, or outside it, and thus succeeded in evading the Aktions.

These Jews returned to the ghetto with the drop in the wave of exterminations, not only because of their desire to be near the remnants of their relatives and acquaintances, but also because these Jews found themselves more secure

[Page 147]

between the walls of the ghetto than in Aryan areas. There was the great danger that people on the outside would, for a reward, inform on them, thus causing the escapees to be sentenced to death for the misdemeanor of having left the ghetto.

All told, the Jewish population by November 1942 had lost about 255,000 people who had fallen victim in the Aktions, which had occurred in the second half of 1942. To this number was added an unknown number of those killed in concentration camps and in crushing labor. The ghettos had been almost emptied of their inhabitants, due to the mass extermination and to the considerable number of Jews who were taken to forced labor camps, or those who were held separately from the remnant ‘lacking usefulness.’

4.The Pause of the Winter 1942–43: The fate of Jews vital to the war effort

Despite the desire of the S.S. men, the Ukrainians and Poles were not qualified to fill the places of the Jewish professionals in the weapons industry.

Already in the course of the wave of extermination in the second half of 1942, serious disruptions had occurred in the supply of weapons, in the economy, and in the war industries, due to the loss of Jewish professionals. The matter reached the point where the most urgent work no longer operated on the timetable.

On September 18, 1941, the governor of the region warned, while writing to the OKW, “Keeping the Jews away is causing a situation where the potential of the Reich has gone down greatly, and the supply to the front and to the S.S. troops will be forced to cease for a while.” The situation was significant, even to Himmler's Supreme Command, for the course of The Final Solution of the Jews of Galicia by the end of 1942. For Himmler's part, it was necessary to leave the minimal number of the most vital Jews alive while they were operating in few places.

In light of the primary priority, which the S.S. men gave to the extermination of the Jews, the demands of the HSSPF and the SSPF, concerning leaving vital Jews alive, seemed suspicious and not serious. In intense arguments, which they carried on with the men of the Wehrmacht, the S.S. men succeeded in reducing, to a bare minimum, the number of vital Jewish professionals.

By August 29, 1942, at the beginning of the mass destruction at Belzec, the governor of the District of Galicia in the “News of the Week” warned:

The labor force in the District is being exploited to the maximum. The matter stems from the severe shortage of Jewish professionals. It was incumbent upon the District of Galicia to prepare everything within less than a year, while in its possessions was a labor force poor in its professional capacity, as opposed to the rest of the districts. Therefore, the war economy was damaged more than in other places by the Aktions against the Jews.The basic question, whether to give preference to the liquidation of the Jewish People over the war effort, has been solved by preference of the matter of the liquidation of the Jews, for political reasons. Despite this, one should take into consideration the steep decline in the ability of staying–power in the war effort, in the affected areas. I hereby declare that the results of this decision will be clearly felt in Galicia.”

Despite the predicted worsening of the situation, due to the extermination of the Jews in the second half

[Page 148]

of 1942, the Wehrmacht relinquished its demand for the war effort, and thereby submitted to the S.S. ambitions for exterminations.

In conversations which were conducted between its men, the OKW and the leadership of the S.S., it was decided to transfer the Jews who had worked until then under the command of the Wehrmacht, to the HSSPF, and from then on to call them, “Hard Labor Prisoners of the HSSPF.”

Now Katzmann was able to filter out anew, and without anyone disturbing him, those Jews who had remained in the weapons industry against his will (November 1942 Katzmann's Report S.100). Jews who were not connected directly to the weapons industries were fired immediately without even worrying about filling their places.

To the restricted circle of Jews whose talents were impossible to replace, armbands were supplied, on which were printed the letters ‘R’ and ‘W.‘ The R and W Jews were housed in barracks which were built for them by the HSSPF and which were called JULAG, Jewish Labor Camp. In the Tarnopol Ghetto, a special quarter was set aside for JULAG. The management of the place was entrusted to Untersturmführer Richard Rokita, the legal proceedings against whom have not been completed and therefore have been severed from the main trial. From here on, Katzmann ‘separated the straw from the kernel.’

In their multitudes, even the families of the professional Jews who had remained alive until now were sent off for extermination, and all those Jewish officials, Committees of the Community and other workers who had survived in the diminished ghettos, were now proclaimed superfluous and ready for extermination.

A matter of the past, no longer considered, was whether for reasons of propaganda, the Germans would keep the families of the Jewish workers from destruction, so as not to trouble Aryan workers with pain and sorrow. From now on, there was no longer a need to take the matter into consideration, since the end of the few professionals who still remained alive was already visible. There was no longer a need even for the Committees of the Community, since the communities had been almost totally exterminated.

Despite the proceedings, the individual imprisonments, and the murders, the winter of 42/43 constituted a last pause for Tarnopol Jewry. It was caused by the destruction of the Belzec camp, so that there should not be any incriminating traces or evidence. At the end of 1942, all the buildings were demolished. All the installations were removed. All incriminating traces were gathered and burned.

The Jewish Labor Commandos were ordered to exhume the hundreds of thousands of corpses from their mass graves and to incinerate them with the help of huge wooden logs immersed in gasoline.

In the spring of 1943, a young pine forest occupied the place of the notorious Belzec Extermination Camp, in which over 390,000 people were murdered, an especially modest estimate.

The hope, which the remaining Jewish remnant cherished during the relatively quiet winter of 1943, was that the Germans would not adversely affect the most vital workers in favor of German victory. But that hope was absolutely shattered. Already, at the beginning of the winter, Himmler had succeeded in pushing forward his position, that all Jews must be liquidated without any consideration of possible damages. Logic and expediency no longer were in play. In a speech that he gave in April 1943, in Kharkov, in front of the S.S. Commanders, he expressed his outlook in a few words:

As good nationalists, our motto is ‘Purity of Blood,’ and this is the first time that we have turned it into deeds. The question of Purity of Blood is not identical to Anti–Semitism.

[Page 149]

It is the equivalent of searching for fleas. Getting rid of fleas is not a weltanschauung, an outlook, a world view. It is a question of cleanliness. Anti–Semitism, to us, is not a question of outlook, but a matter of cleanliness. The problem has almost come to its solution. Soon, we will be free of fleas.

The army men and commanders of armaments gave up on their demands for leaving a Jewish professional labor force in especially vital places, in the face of Himmler's abysmal and blind hatred. Also contributing to this was the weak and submissive character of their commander in the OKW, the General Field Marshal Keitel, who was a total follower of the authority of the leadership of the NS. He gave his consent to Himmler, early in November 1942, in the matter of the immediate removal of all Jews employed in German positions. Therefore, Himmler's order removed the last serious obstacle to the total destruction of the Jewish population in the region of Galicia.

5. Last Wave of Extermination

A few more months passed until the Deportation Department in Tarnopol received the order to begin the final extermination. After the demolition of the Belzec Camp, there was a need to return to using the Shooting Commandos, and for that reason, they waited until the main part of the winter.

And then the Aktions began, from March through June, and they repeatedly struck in the town, ‘until the last wick was extinguished.’

Everything happened in a similar way to the previous shooting Aktions, except that this time the victims were forced to strip their outer garments at the time of assembling, and then to strip completely near the graves.

The methods of gathering the victims became more barbarous and cruel, since the victims, in the bitterness of their despair, held together their hiding places with their fingernails, and only with great difficulty was it possible to find them.

In page 24 of a report from June 30, 1943 to Katzmann's staff:

At the time of the Aktions, we encountered especially serious problems. The Jews had indeed not escaped from the place, but they hid in every possible hole and corner, in order to evade the decree. They entered sewer pipes, hid in chimneys and privies. They attempted to fortify themselves in subterranean tunnels, in cellars serving as bunkers for them, in the cleverest hiding places, in floors, in grain–heaps and in furniture.

Only in a few places did the number of victims amount to the same number as in the previous Aktions of the fall of 1942, and quickly subsided afterwards.

The immediate victims of the present Aktions were Jews of R and W. After these Jews, the Germans exterminated the Committees of the Community, and policemen, and their families. With the conclusion of the Aktions, the ghettos were cleaned out in a short time, and every Jew who was discovered was shot to death.

6. General Numbers

At the conclusion of this extermination push, there was officially not a living Jewish soul in the region of Tarnopol nor in the expanses of the district of Galicia.

More than 41 Aktions were credited to the Deportation Department in Tarnopol, in which between 34,000 and 40,000 victims were murdered.

A tremendous but unknown number were killed in pogroms, in concentration camps, and in lone individual Aktions,

[Page 1590]

or as a result of the frightening suffering prevailing in the ghettos. Death still waited for 21,156 Jews who were in 21 remaining labor camps.

Katzmann reported that: “For the security men, there still awaited serious ‘ants'– work’ in the attempt to discover Jews, who camouflaged themselves or hid.”

Katzmann's men engaged in their liquidation, during the summer of 1943, by shooting small groups of Jews who were seized. Their number does not appear at all in Katzmann's list of victims. The number of victims from Katzmann and the National Socialists in Galicia's extermination policy, is estimated, up to the date June 27, 1943, at about 434,329 people.

Twenty Five Years Later

By Y.B.P.

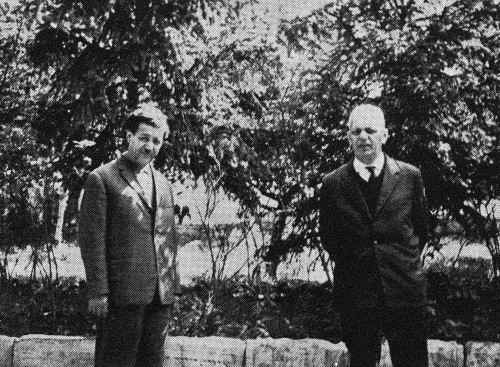

“Mr. Witness,” the Chief Justice began his words. “Is there any family relation at all between you and the Defendant Müller?” This question sounded like a macabre joke, as if it was not of this world, in which the sad and the ridiculous were mixed. The question was one of the least pleasant inscribed in my memory from that trial in which I testified against the heads of the Gestapo of Tarnopol. The Court was in Stuttgart, and the trial took place in February 1966.

After I replied to the Judge's question, with not just a little astonishment, the Chief Justice explained to me, apologetically, that legal procedure obligates him to ask that question, even though it is certainly not pleasant for the witness.

I happened to testify at the Stuttgart trial almost by chance. About two years before the trial, I had submitted testimony with the Israeli police, after I had encountered an advertisement in the newspapers. It did not occur to me that this testimony, which I had submitted in Tel Aviv, would bring me, in days to come, to testify in front of the Court in Germany, a country that I did not rejoice in re–visiting after I had left it in 1947.

Müller had been the head of the Gestapo in Tarnopol, and he bears the responsibility for the liquidation of the Jews of the district of Tarnopol. He had personally supervised most of the Aktions in Skalat.

Before there was a Ghetto in the town, I had worked in the delivery of newspapers. My father was also involved in this work, and I helped him bring the German newspapers principally to unsafe places, which did not usually endanger me, when I was a boy, 11 years old. As a result, I encountered Müller, at least twice before the Great Aktion, when I would bring the newspapers to the Shofo building, which was in the house of Dr. Kron.

At the time of the Great Aktion of October 1942, I was seized, and brought to the Great Synagogue, and there I saw Müller conducting the work of the liquidation of the Skalat Ghetto. I saw Müller shooting into a crowd of people who were gradually being trampled in the synagogue. Since not many were left alive who were able to bear witness against Müller with direct testimony, the Israeli police, who elicited the statement from me, thought that my testimony possessed importance and that it was in my ability to aid in his conviction. The principal problem, which was liable to influence the admissibility of the testimony, stemmed from the fact that I was 11 years old at the time of the Aktion.

About two years passed since I had submitted my statement in Tel Aviv, and the matter had been forgotten from my heart, when suddenly it was reported to me that I was to travel to testify in Germany. Since I was a soldier in regular service, it was not convenient for many reasons, but my commanders related to the matter with much understanding, and my trip was authorized.

[Page 152]

I was scheduled to be a witness the day after I arrived in Stuttgart. I asked to testify in the Hebrew language, for reasons of both convenience and principle. The matter caused a bit of a burden for the legal authorities, since most of the witnesses testified in Yiddish, Polish or German, and they had to engage the rabbi of the city to interpret. He was an Israeli serving in the rabbinate, temporarily, of course.

Ten Germans were standing trial. Of them, I recognized at least three: Müller, Roebel, the commander of the Kamionka and Skalat camps, and his assistant, Meller. Even though their facial appearance was well–etched in my memory, I was not qualified to identify any one of them, considering the 24 years, which had passed since then. And, more than that, they were wearing new, different clothes, not their Nazi uniforms. To my good fortune, I was not asked to identify Müller. I mainly testified against him. During the trial, I was also asked about Roebel.

After I was sworn in, and after the Chief Justice had asked a series of questions, I was asked to repeat before the Court the main points of the testimony, which I had submitted two years earlier in Israel. Immediately, it became clear, as expected, that the focus of my testimony would be in the matter of Müller's shooting into a crowd at the synagogue, on the day of the Great Aktion. These shots were bound to hit people, although I was not able to testify clearly who was hit by them, even though I had seen people wounded and killed inside the synagogue. After I had concluded my testimony, the examination began in which the defense attorney opened.

As expected, the defense counsel began with the weak spot of my testimony, my age, and the time that had elapsed since then. Among the rest, he asked me how I could claim with such confidence that the man who fired was indeed Müller. I replied that, “as of today, I don't know who Müller is,” and it became clear that the scoundrel had absolutely changed, wearing eyeglasses and, he wasn't called Müller at the trial. But I always saw him in uniform and with a hat. I was able to establish that the man I saw shooting was identical to the man I saw in the Schutzpolizei, at the time that I was bringing the newspapers there. This answer invited, on the part of the defense attorney, a question that I expected to be asked. “Mr. Major,” (that was my military rank in which I appeared in court) – the defense attorney turned with quite transparent cynicism – “you claim that you were delivering newspapers. Can you mention to the court the names of the newspapers which you delivered?”

I understand German, and since I had expected this question, I had refreshed my memory about which newspapers I brought to the Germans, before the trial. I had an answer prepared immediately. I allowed the interpreter to translate the question calmly, and after thinking for a few seconds, I began to count a long list of the words of filth, which were used by the Nazi press, beginning with the Völkischer Beobachter and ending with the Stürmer. While I was counting the newspapers, one after the other, I did not take my eyes off the defense attorney. I was impressed that he did not particularly enjoy my answer to his question, which was intended to trip me up. The whispers emanating from the benches of the jurors told me that this had not been a successful question.

The defense attorney's follow up question was also rather foolish. At the time that I testified about the manner in which Müller had shot, I had said that, according to the angle of fire, the bullets were bound to hit people. The defense attorney bore down on the term ‘angle of fire,’ which the interpreter had translated as Schusswinkel. He argued that it was a professional term, and that as a boy, I could not have known either its meaning or its essence, and that as a military man, I was inventing it now, just as I was inventing the entire story, in order to mislead the court.

[Page 153]

I immediately replied that the defense attorney was correct, that ‘angle of fire’ is a professional term, and that I recognize it only now in such a capacity. But in this there is no contradiction to the manner in which Müller had shot, and that when I mentioned ‘angle of fire,’ I intended to concretize for the Court the certainty that Müller's shots had hit people.

After that, I was asked another long series of questions about Müller and Roebel. The defense attorney concluded with a question in which I was asked to describe the Great Synagogue in maximum detail.

I knew the Great Synagogue well, and I remembered with detail and great precision not only its walls, its ceiling and its windows, but also the content of part of the fresco paintings that covered the walls and ceiling. All those details, and even the smallest, I described with specificity.

When the turn of the Prosecutor came, he asked me only two short questions: “When did you last see the Great Synagogue?” I replied “In October 1942.” “Did you also then see the Defendant Müller shoot in the synagogue?” I replied “Yes!” With this, my testimony ended.

The Court session was concluded, and the Prosecutor invited me for a conversation in his office. Among other things, he explained to me that the Defense attorney's question about the description of the synagogue had served the prosecution. He said that my detailed description brought credibility to my testimony about Müller's deeds, especially since the defense would attempt, at the time of the summation, to weaken the effect of the testimony with the argument over my young age, and the amount of time elapsed since then.

On the following day, I left Germany, but with no further thought of revenge. I also doubted the measure of severity that is expected for the defendants in a German court. My doubts grew even greater when I found out that the Chief Justice was a Jewish apostate, a Jew who had converted to Christianity.

I found out that Müller indeed was sentenced to life imprisonment. This Müller had brought destruction upon most of the Jews of Skalat, and upon all the members of my family. Was it made easier for someone that this evil murderer was sentenced to life imprisonment? I doubt it very much. It is probable that one who ascribes the supreme value of justice will come thereby to some small satisfaction, but only partially. It seems to me that the significance of this trial, and its importance, is far beyond the justice that was done for the sake of the ones who were murdered.

from the book Wars of the Ghettos

By Tzipporah Birman

Everything is lost. This is our fate: to atone for the sins of the previous generations.

We have mourned them all, have ached for their loss. The most awful event which was liable to occur in history has come upon us. We have seen. We have heard. We have ached. Now it has been decreed upon us to be mute for eternity. All the bones will not even be brought for a Jewish burial. It is difficult. There is no plan other than to fall with honor, together with the thousands who went to their deaths, without panic, without fear. We know: the Jewish People will not be destroyed. We will arise to resurrection. We will grow and will flourish, and will avenge our spilled blood.

Surely, with this I turn to you, Comrades, wherever you are: you are responsible to avenge. Day and night, I do not keep silent from the command of revenge. Avenge the spilled blood, just as there is no silence for us, face to face with death.

Cursed is the man who will read this, sigh, and return to his day's work.

Cursed is the man who will shed tears, and mourn for our souls, and say “enough!”

Cursed is the man who will read this, sigh, and return to his day's work.

Not this we demand of you! We, too, did not mourn for our parents. Silenced and keeping silent, we saw the corpses of our dear ones, who were shot like dogs, lying there.

We call to you: avenge, avenge without mercy, without sentiments, without ‘good’ Germans. The ‘good’ German – for him, an easy death, but with death, may he be killed eventually. They, also, promised the Jews right to their eyes: “You will be shot last.”

This is our demand, the demand of all of us. This is the burning demand of people who tomorrow, it's probable, will fall on those falling, will fight with might and fall with honor.

To avenge, we call upon you, you who have not been afflicted in the hell of Hitler. That is our demand, and you are obligated to do it, even with mortal danger.

Our crushed bones will not know rest, scattered in all ends of Europe. There will be no silence for the ashes of our bodies, strewn to the wind, until you take our revenge.

Remember this and do it: it is our request; it is your duty.

[Page 155]

Witness: By Fischel Goldstein

In 1967, I left Poland to visit friends from Skalat who lived in Lvov, Ukraine. A policeman, a friend of the Skalaters, agreed to take us in his automobile for a one–day visit to Skalat.

The journey from Lvov to Skalat took two and a half hours. A paved road, wide in expanse, which branches off eastward to Kiev, crosses the cities and villages: Zlochov, Zaburov, Tarnopol, Borokivilki, and Kolodiovka – until you come to Skalat.

Skalat – a destroyed city. Nothing remains in it from the days of its past. The destruction, which the Germans wrought upon the city remains as is. The Russians did not attempt to rehabilitate the city at all from its ruins. I traveled from Mantiva to Kariba and almost did not see that I was in the midst of a city.

|

|

[Page 157]

From the former 3rd of May Street, in the heart of the city, you can distinguish the train station, which is outside the city. The entire area, which had been highly populated, is newly empty of houses.

Which houses still stand on their foundations? The Starusta Building now serves as a school for kolkhozes, collective farms. A workshop for wheat is now in the house of Kron, the lawyer. The post office is located in its repaired building, so too the hospital. The Sokol Athletic Society is now a municipal culture house.

On 3rd of May Street, a few houses still stand: The Tenenbaum House, the Teller House, the Rosenzwieg House, the Kosovsky House, the Mager House, the Gelbtuch House, the Grobman House. And so too, the huge business house near the City Hall.

|

|

The well–known quarter, Haftzini, was totally destroyed. The marketplace stretches in a portion of the quarter, just as it was in the days of Polish rule in the town.

Not a trace remains of the Catholic Church, which stood not far from here, and glorified the city with its beauty. A number of solitary houses stand out at a distance not too far from here.

In the street leading to Horodnitza, solitary houses stand from their former days – the Katz House, the Muni Pickholz House. Desolation and emptiness are all around.

The railroad station has kept its character and its form. The same very old building. Only freight trains now visit the station. Passenger trains no longer arrive. What was once Yosef Weintraub's house, south of the train station, still stands, complete as it was.

[Page 158]

Gentiles and Russian officials reside in the houses of the Jews who left in order to survive. The population of Skalat is now scanty. In total, there are 1500 people in the entire city.

There are only four stores. A store selling meat and sausages is in the house that Rozya Bernstein lived in. A business selling electrical appliances is in the Rotstein house, opposite the Ukrainian church. In the home of Zolnadzyah, there is a grocery store. And at Grobman's, a restaurant has opened.

The municipal garden near the school is completely destroyed. In it is a collection of memorial stones, which were brought here from the nearby Jewish Cemetery.

The city is poor. The clothing that the people wear is old. Progress lags here by hundreds of years. The city has contracted so much that not even a police station is located here. But there is one movie theatre. The people of the city earn their livelihood from the kolkhozes, the collective farms, in the vicinity, and also from the limited commercial sector.

The memory of the Jews of Skalat who were exterminated comes up in every conversation with the gentiles of the place. They mention the names of Jews who helped them. They express sorrow for everything that happened, and describe the ‘Journey of Caravans’ of Jews to the death pits. For a brief moment, it seems that the disaster, which befell us, pains them. They would want to return to the days of the past. They justify themselves that the fault is not on them for the disaster which befell us. They bring up Dr. Chilkowski as an example of humane behavior of Christians toward Jews in the days of the Holocaust.

They may say what they say. There is now not even one Jew in Skalat. The Holocaust here is absolute. There remained here only poor and paltry signs of the life of the Jews in days past.

They turned the Jewish Cemetery into a stadium. The monuments were removed and sold to gentiles for construction purposes. The fence surrounding the Starusta is built from memorial stones from the cemetery. Even the sidewalks on Pilsudski Street are paved with memorial stones. The soil of the cemetery, with its many graves, moves and shakes without let up. And during a soccer game, one of the players stumbled, and he fell into a gaping grave.

Today the old cemetery fence surrounds the stadium. They straightened the area of the cemetery with the help of tractors. The bones of the dead were collected and buried on the spot. With a huge press, the ground over the graves was flattened. All those details were made known to me by my friend from childhood, Kravitz.

The magnificent synagogue from former days still exists. Its appearance is like a burnt–out ruin. Broken windows are covered with boards. A workshop for frames is located inside. The business is not large. Three people in all work there. A toilet was installed in a corner of the synagogue. The paintings and decorations that once adorned this holy sanctuary are still visible on the ceiling.

The area around the synagogue is empty and deserted. There is no longer any trace of the many synagogues which were here, all around. They have disappeared completely.

At some distance from the city, stretch ‘the pits’ – the mass graves of the Jews of Skalat. The spot is hard to find. All of it is covered with wild growth, trees and grasses. It's impossible to find any sign

[Page 159]

of a grave here. A person passing by the place would not think that a multitude of people is buried here. The Gentiles who accompanied me here stood silent. The sorrow of this place was recognizable even on their faces.

A shocking experience awaits the person who visits Skalat, so many years after the Holocaust. This is the city in which I was born. I knew it in each stone and in every spot, and now I do not recognize it. I stood for a moment at the place where my house once stood. Nothing was left of it. Only the kiosk in which I had worked stands in its place today. In its entrance stood a Russian girl who even found it proper to apologize to me, and to remove from herself any guilt for the changes that had occurred.

There indeed was a town, and its name was Skalat. It no longer exists.

|

|

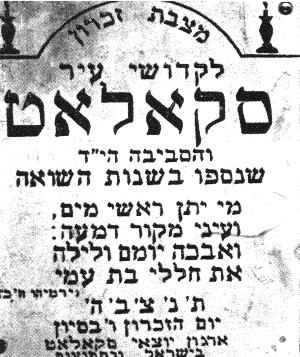

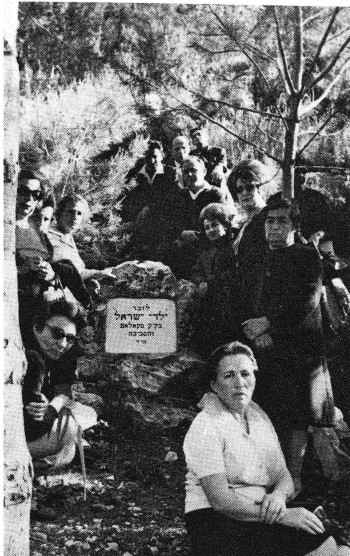

May the Lord Avenge their Blood, who were Swept Away during the Years of the Holocaust |

And my eyes a fountain of tears

That I might weep day and night

For the slain of the daughter of my people

Jeremiah 8:23

May their souls be bound up in the bond of everlasting life

Memorial Day, 6th of Sivan

The Organization of those Originating from Skalat in Israel and the Diaspora

|

|

|

|

fulfilling our mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied, sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Skalat, Ukraine

Skalat, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Jason Hallgarten

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 10 Dec 2020 by JH