(By hovering your mouse cursor over the superscript footnote number in the text,

the wording of the footnote will appear in a pop-up box.)

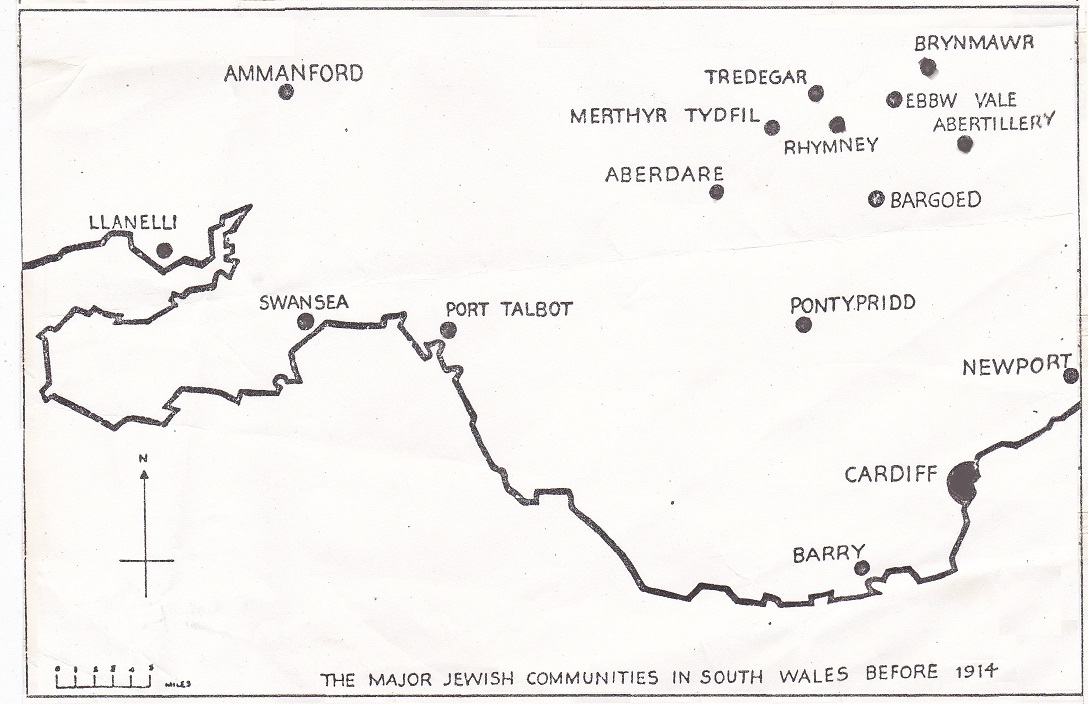

The Jewish communities which developed in South

Wales in the second half of the nineteenth century based

themselves upon the growth of the coal, iron and tin-

plate industries of that region. They were as much

products of industrial South Wales as the mining and

metallurgical industries, and the difficulties which

confronted them can and ought to be seen, in part at

least, as a by-product of problems attendant upon rapid

industrialisation. The history of these communities

down to the First World War does, in fact, provide a

graphic illustration of the role which Jewish

communities traditionally play as scapegoats for economic

ills and industrial unrest.

Historically, the earliest Jewish community to

develop in South Wales after the Readmission was that of

Swansea; according to the Standard Jewish Encyclopedia,

German Jews settled in Swansea in the 1730s, though

there is evidence that they were Lithuanian Jews intending to go to America.1.

In 1740 David Michael, a founder

member of the community, built a wooden synagogue behind

his house in Wind Street, near the docks; it could hold

about 40 people. This structure served until 1789,

when a new building, also of wood, was erected on The

Strand nearby. This was replaced in 1818 by a larger

structure, with a capacity of 60-70, in Waterloo Street,

and this in turn gave way, in 1859, to the Goat Street

synagogue, the one which German bombs destroyed

in 1940.2. When the

Goat Street synagogue was opened, Swansea Jewry

could not have numbered more than about 50

souls.3.

Within the next 40 years, the size of the community

increased six-fold.4.

By far the greater part of this

increase came from immigrant Jews from eastern Europe.

And just as, in London, the immigrants shunned the cold

formalism of the cathedral-like synagogues already

established there, so in Swansea they founded their own

Beth Hamedrash, in Prince of Wales Road, in 1906.

Indeed, until the end of the Second World War, Swansea

Jewry was divided into two religious groupings, And

though, as the years wore on, the difference became more

apparent than real, in the beginning it had a definite

meaning. Goat Street was the spiritual home of the

Jewish 'establishment`; 'Prince of Wales Road was the

abode of the immigrants, Yiddish-speaking, poor (at least

to begin with), but probably more orthodox. The

established Jews, though without doubt the descendants of

peddlars, were themselves by now shopkeepers and

tradesmen; the newcomers tramped the valleys of west

Glamorgan, Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire, learning

the language of the native Welsh, doing business with

the rapidly-developing mining communities, and very

occasionally (as at Ammanford) deciding to live among

them. Often they did not establish separate synagogues,

but met for prayer in a room provided by one of their

number. The Port Talbot community was organised at the

turn of the century by Raphael Levi, a Lithuanian

immigrant, at Aberavon, but a synagogue was not erected

till after the First World

War.5. At Ammanford a

synagogue was never built. Of these very small

communities in south-central and south-west Wales, to

which Swansea ranked as a large Jewish centre, almost no

trace (except descendants) now survives.

The one exception is Llanelli. There is no

record of Jews in Llanelli prior to the 1880s. The

nucleus of the community was provided by Isaac Benjamin

Jeffreys, who arrived in 1887, and his two brothers,

Lewis and Morris: they were all glaziers. Later

arrivals were credit drapers and pawnbrokers; the first

pawnbroker's shop in Llanelli was opened by a Jew in

1897. Religious services were held in the home of Harris

Rubinstein, for the synagogue in Queen Victoria Road was

not opened until

1909.6. By

any standards the community

was minute: 70 Jews, according to the

Jewish Year Book

of 1914, in a gentile population of over 25,000.

Jews were attracted to Swansea, Llanelli and

Ammanford because the growth of the metal and mining

industries in the second half of the nineteenth century

had created new entrepreneurial opportunities in a rapidly

expanding population. The same is true of west Monmouth

and east Glamorgan. Jewish peddlars and tradesmen were

naturally attracted to the Welsh mining centres. The

Merthyr Tydvil community was founded in 1848; the

Aberdare community dates from at least the 1860s, and

that at Pontypridd can be traced back to

18677. The

developing industrial areas situated in the Western

Valleys of Monmouthshire formed a particular area of

Jewish settlement. A synagogue was not opened at

Newport till 1869, but the community there was then

already ten years old.8. Similarly,

the synagogue at Tredegar was founded in 1870 to serve a community which

had been established several years

before.9. Russian

refugees who went to South Wales at first attached themselves to these already-established communities, but

soon spread outwards to Abertillery, Bargoed, Ebbw Vale,

Rhymney, and the surrounding localities as far north as

Brynmawr in Breconshire.

For these Jews of Monmouthshire and East Glamorgan,

Cardiff fulfilled a role similar to that of Swansea in

relation to their co-religionists in the west. Although

there are instances of Jews having lived in Cardiff in

the eighteenth century, a community was not established

there until the 1840s: the land for the Jewish cemetery

in Cardiff was presented by the Marquis of Bute in 1841.

A permanent synagogue was soon established in a room in

Trinity Street, near the market; then it moved to larger

premises in Bute Street. In 1858 a synagogue was opened

in East Terrace to serve a community then numbering

perhaps 150 persons. At the same time the community

acquired its first Minister - Nathan Jacobs.

The Cardiff Jewish community, as it developed

during the Victorian period, was a business one par

excellence: watchmakers, jewellers, 'slop'-sellers, tailors,

pawnbrokers and general dealers.10. It

was prosperous.

tightly-knit and exclusive. Discipline of members, as

revealed in the Congregation Minute Books, was rigorous.

In August 1880 it was decided that a policeman should be

present at East Terrace during the forthcoming high-holydays 'to prevent non-subscribers entering the

Synagogue.11. Discontent

with the high-handed, over-bearing attitude of the anglicised communal leaders

eventually led to open revolt. One source of trouble was

arrears of payments of subscriptions and seat-rentals;

another was criticism of the spiritual leadership. In

1878 the Minister, the Rev. I. Lewis, had been given six

months' notice to quit 'unless he conducts the service

with more devotion'; in 1885 Mr. M. Lewis was appointed

shochet and mohel at £70 per annum, and two years later

the Rev. J.H. Landau was appointed Minister and teacher

at £100

per annum.12. These

appointments did not, however, meet with universal approval. A group of 'seceders'

had established their own chevra in Edward Place some

time between 1889 and 1890, and had enticed to their

side a shochet, the Rev. J.B. Rittenberg. The delegate

Chief Rabbi, Hermann Adler, was prevailed upon to withdraw his endorsement of Rittenberg's

shechita and to tell

the seceders that animals slaughtered by him were trefa.

But reinforced by the adherence of recently-arrived

immigrants, the seceders were not to be put off so

lightly. In March 1889 they made a formal approach to

Adler to appoint for them a chazan and shochet. He

interviewed representatives from both sides, but was

unwilling to press the seceders to withdraw. 'Your

decision', Mr. I. Samuel, of East Terrace, wrote to

him, 'can have but this effect, that instead of Cardiff

having as now one good Congregation with an English

minister and teacher, a school open and free to all poor

children, it must revert to its former state of affairs,

when a foreign Shochet will be the Jewish representative

and the rising generation will be deprived of Jewish

education.13. But

Adler would not apply further

pressure. The Edward Place synagogue came into being,

and in 1897 acquired its own marriage

secretary.14.

Although the breach between the two Cardiff

communities was now complete, the East Terrace synagogue

remained the more prestigious of the two: it was the

synagogue of Cardiff's Jewish establishment. When

Colonel A.E.W. Goldsmid came to Cardiff in 1894 as

Colonel-in-Command, 41st. Regimental District, he

naturally joined East Terrace, and was the prime mover

in the project to build the new synagogue in Cathedral

Road, opened by F.D. Mocatta and consecrated by Chief

Rabbi Adler on 11 May

1897.15. Goldsmid's

presence in

the Welsh capital gave Cardiff Jewry some national

prominence. The founder of the Jewish Lads' Brigade,

he had become a devoted Zionist, was founder of the British Zionist

Federation, and took part in the El Arish Expedition of 1903. When Herzl

visited Cardiff, it was primarily to interview Colonel Goldsmid. He died, like Herzl,

in 1904.16.

By the turn of the century, Cardiff was the undisputed capital of South

Wales Jewry. It had a Jewish population of about 1,500, two synagogues (and

for a time between 1901 and 1904, an immigrant-inspired Beth Hamedresh as

well), a Board of Shechita and, in 1905, a Jewish Naturalisation and

Political Association. It also boasted a Board of Gaurdians, founded in

1900, which in that year alone relieved 230 cases, one-third of whom were

alleged to be 'professional beggars'. The board soon ran into financial

difficulties and by 1904 had been

wound up.17. At

the other end of the

social scale, well to-do Cardiff Jews were making the familiar moves west

and east to newer residential areas, to Grangetown, Riverside, City Road and

Newport Road. Louis Samuel, who died in 1906, provided the city with its

first Jewish J.P., and Lionel Fine, born in Rhymney in 1865, was appointed a

J.P. in 1904. The community, at least as far as its leadership was

concerned, appears to have been as integrated as any section of Anglo-Jewry

at that time.

Around Cardiff, meanwhile, to the north and west, a dozen or more Jewish

communities had established themselves. Foremost among these were Merthyr,

with a literary & Social Society, a Naturalisation Society, and a branch of

the Chovovei Zion and Newport, which had its own Board of

Guardians.18.. At

the turn of the century the Rev. Michaelson, Minister at Newport, was paying

weekly visits to Tredegar and

Brynmawr.19. But

each of these latter

communities had its own shochet who presumably officiated at services in the

synagogues which each

possessed.20. Other

Jewish centers in East Glamorgan

and West Monmouth did not (with the exception of Abadare) possess an

excluive shochet, but all had synagogues (usually converted houses or rooms)

with a cheder attached. Fed by periodic influxes of Russian refugees, South

Wales Jewry spread itself into every major town and many minor villages and

hamlets. Yomim Noraim services were held at Barry Dock for the

first time in 1904.21. The

synagogue at Ebbw Vale was

not formally opened till 1911, when its congregation

numbered about 80 persons.

In numerical terms all these communities were

minute. In 1914 the 135 Jews of Brynmawr represented

2.6 per cent of the town's population. Tredegar Jewry,

160-strong, amounted to approximately three-quarters of

one per cent of Tredegar's inhabitants; in Abertillery

there were 100 Jews, less than half of one per cent of

the population, with Merthyr's 300 Jews representing

roughly the same proportions while at Newport there

were 250 Jews, just over a third of one per cent of the

inhabitants. Swansea's 1,000 Jews amounted to just

over one per cent of Swansea's population. Even the

largest number of Jews in South Wales, the 2,000-strong

Cardiff community, comprised only slightly more than one

per cent of Cardiff's total population. The Jewish

populations of the newer areas of settlement in

Glamorgan and Monmouth were too small even for the Jewish Year Book to bother to mention separately. It

is very doubtful whether, on the eve of the First World

War, South Wales Jewry amounted to 5,000 souls: the

total may well have been nearer 4,500.

That such small, well-ordered communities could

have become the objects of antisemitic outbursts which,

if they were not as long-lasting as those suffered by

London Jewry at the time, were certainly more violent,

seems at first glance difficult to believe. Yet between

the 'Jew Bill' riots of 1753 and the fascist-inspired

outbreaks of the 1930s, the attacks upon South Wales

Jewry in 1911 stand out as the only example of

organised mass antisemitic violence in Great Britain.

I have examined in detail elsewhere these anti-Jewish

riots, which took place in August 1911 in the Western

Valleys of Monmouth.22. Here,

at the risk of repeating

some of my findings, I wish to place these riots in a

somewhat broader context.

Victorian Jewry in South Wales was a mercantile

community which established itself and grew as a result

of the expansion of trade and industry there. But

this industrial revolution, which seemed to offer so

many opportunities for Jewish trading talents, contained

within itself the seeds of subsequent misfortune. The

explosive growth of the coalfields in industrial South

Wales in the late nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries had attracted to Glamorgan and Monmouthshire

thousands of migrants, at first from neighbouring

welsh counties. but later from south-west England and

from even further afield.23. Of

the total population

enumerated in Glamorgan and Monmouthshire in the census

of 1911, 35 per cent and 37 per cent respectively were

returned as having been born outside the county in which

they resided; over 20 per cent in both counties had

been born outside Wales. At first the native Welsh

were able to absorb the newcomers. But the process

of assimilation was unable to keep pace with the

continuing influx of migrants.24. There

was a 'head-on

collision' between different cultural

identities.25.

When this confrontation was reinforced by strong ethnic and/or religious

differences, open conflict was difficult to avoid. To the native Welsh the

Jews, however few in number, however well established, however worthy,

however fluent in the Welsh language (as many of them were), remained

foreigners and interlopers, 'a small and separate class, convenient for

attack'.26. The

Jews in South Wales, unlike the Irish,

did not work longer hours, take lower wages, or accept

inferior living standards, to the detriment of Welsh

miners and factory workers. Indeed, though it is

impossible to say for certain that (prior to 1914)

no

Jew in South Wales was a coal-miner, or a blast-furnaceman, or a tinplate-worker, it is equally impossible

to deny that very few Jews living there in the late

Victorian and Edwardian period belonged to the classic

Marxist proletariat.27. They

were poor, often very

poor, but poverty alone was not sufficient to bind

them to the working-class populations in whose midst

they lived. And when, in the summer of 1911, the

eleven-month-old Cambrian Combine strike collapsed,

to be followed by the first-ever national railway

strike, with its own consequent effect upon the

collieries and blast furnaces, the mining communities

of the Western Valleys erupted into an orgy of violence

in which the Jews were the prime, and generally the sole targets.

Accusations that the Jews were taking advantage of the industrial unrest to

raise rents and food prices were, on investigation, found to be false in almost

every case. Nor were the rioters 'hooligans' and 'roughs'; they were miners and

their wives, members of the 'respectable' working classes. Nor were the riots

spontaneous; at Tredegar, where they began, 'open threats' had been made against

the Jews for some time, a fact to which the Rev. Jerevitch, at Cardiff, bore

witness.28.

Yet if it was the misfortune of the Jews to have

come into South Wales at a time of social upheaval, and

to have received its backlash, they were still more

unfortunate to have entered a land seething with

religious bigotry. Here the Welsh Baptists were well

to the fore. The abduction and conversion of Esther

Lyons, in 1868, which created such a storm of indignation in Jewish circles, and which was compared with the

Mortara case, was carried out by a Cardiff Baptist

Minister, Nathaniel Thomas, and his wife; the

subsequent legal proceedings revealed that Esther Lyons

had not been their first Jewish

victim.29. There is no

evidence to suggest that the Welsh Revival of 1904 was

itself philo- or antisemitic; but it is known that some

converted Jews were brought to Llanelli to preach as part

of the revivalist effort

there,30. and it may not be pure

coincidence that attempts were being made at Llanelli at

about the same time to ban shechita without prior

stunning.31. At

Pontypridd there was an 'incident'

involving Jewish voters, and the Cardiff community took

the precaution of forming a Jewish Vigilance

Society.32.

When the riots of 1911 broke out at Tredegar, they began

with a mob of 200 attacking Jewish shops and singing

several favourite Welsh hymn

tunes.33. And when the

Monmouthshire Welsh Baptist Association, meeting at

Blackwood, near Bargoed, on 6 September 1911, was asked

to pass a resolution expressing sympathy with the Jews,

several ministers and others took exception to the

motion; one delegate argued that 'Resolutions did more

harm than good, and they encouraged the Jews. There

were about 100 Jews at Tredegar now, and if they had

many more resolutions they would have 500

there'.34.

The resolution was not passed.

It would be interesting to know what picture of

the Jews was being painted by Baptist ministers in South

Wales in the late nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries; at all events, it cannot have been a very

favourable one. The Revival, certainly. turned many

Welshmen's minds towards social problems. In this

respect it had a long term effect which can be seen at

work during the Cambrian stoppage of 1910-11 and which

may well have contributed towards the concern with bad

housing which was a marked feature of the 1911 riots.

When those riots began, Jews fled from the Western

Valleys in large numbers to Aberdare, Merthyr, Newport

and Cardiff.35. They

had been the victims of organised

attacks by economically-motivated and religiously-inspired mobs; Welsh as well as English newspapers had

no hesitation in calling their experience a

'pogrom'.36.

They returned to the Valleys in due course, but the

memories of 1911 sank deep, and at the end of the Great

War many of them moved permanently to Cardiff where,

incidentally, they appear to have had a noteworthy

revivifying effect upon orthodox religious observance

there.37.

I am painfully aware that the picture I have

painted of South Wales Jewry in the Victorian and

Edwardian periods is a sombre one. It is in the nature

of Jewish history that its darker periods are more

faithfully and more fully recorded than its happier

moments. In the context of Anglo-Jewry as a whole,

the Jews of South Wales were too small at that time to

make a marked impact or create a decisive image. In

the context of South Wales the newspapers of the

period mentioned them only when their sufferings

merited column-space; Tredegar was more newsworthy

than Kishinev. Were it not for the events of 1911,

the history of the Jews in South Wales before 1914 would

be dominated by Cardiff, as that of Anglo-Jewry as a

whole is dominated by London. As it is, the records

tell us precious little about the daily lives of these

Jewish people, their hopes and fears, their family

circumstances, their economic and social status. It is

easier to ask these questions than to answer them. Why,

for instance, were the western communities - in Llanelli,

Swansea and its environs - apparently unaffected in 1911?

Why were Cardiff and Newport untouched? Had relations

with the gentile communities in these areas been of a

different, more amicable order, or did antisemitic

rabble-rousers find it easier to do their work in small,

isolated towns and villages than in the larger urban

centres? And what was it about life in South Wales which

managed to sustain communities which must have been among

the most orthodox of the Victorian era, and which have

produced a half-dozen or more rabbis and ministers of

religion? Was it simply that the Jews who settled in

South Wales were staunchly orthodox anyway? Or was it

also, as I suspect, that the normal pressures of social

and religious conformity in a small community were, in

this case, reinforced by unspoken fears? Although

Swansea, Cardiff and Newport Jewry were well established

before the 1880s, the Jewish communities of South Wales

owed their growth and development largely to immigrants

arriving in the last two decades of Victoria's reign. It

seems likely that these people saw in the religious

fanaticism of Welsh nonconformity echoes of Russian

Christianity at its worst.

(I should like to express my appreciation of the

advice given to me by Dr. Kenneth Morgan, Fellow

of The Queen's College, Oxford, in the preparation

of this paper, for the contents of which I alone

am responsible.)