|

JewishGen Danzig/Gdańsk Research Division Presents:

Interview with My Father, Gershon Yelin (Jelen) by Amy Yelin 16 Feb 2018 |

|

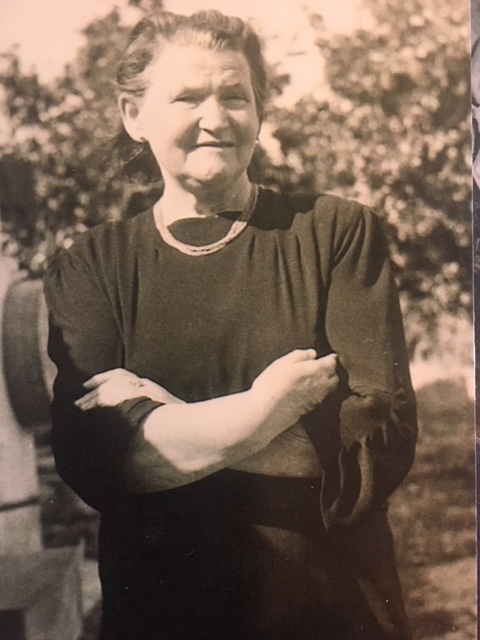

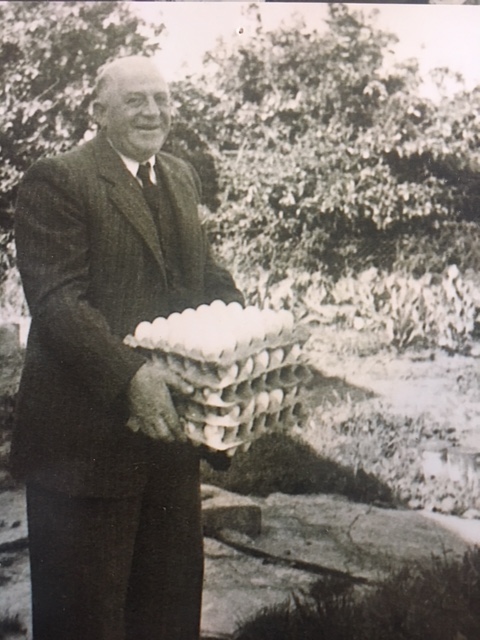

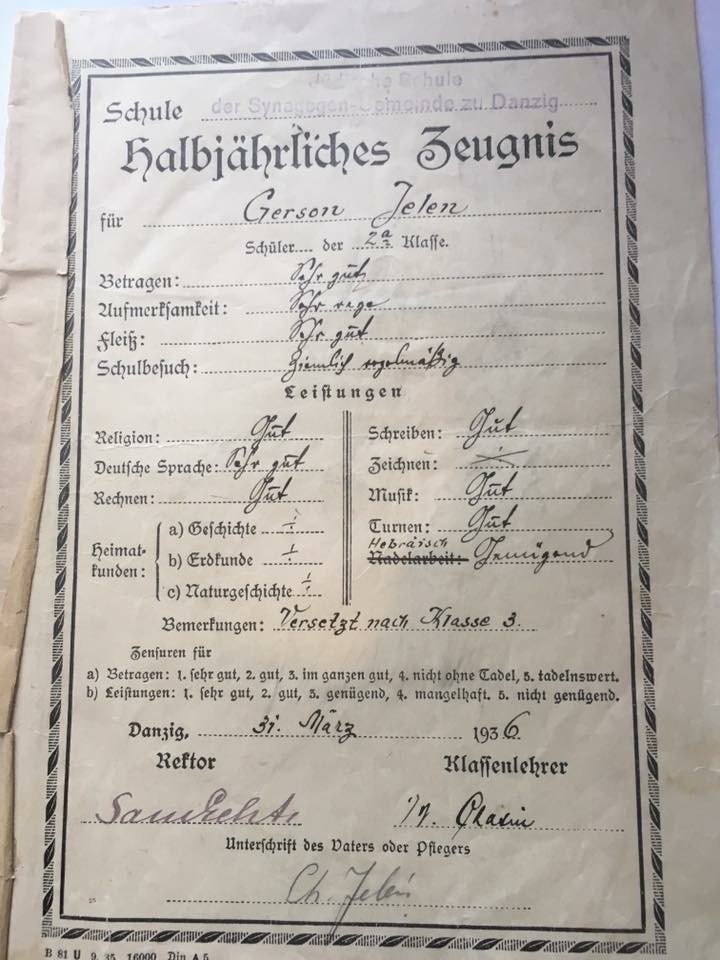

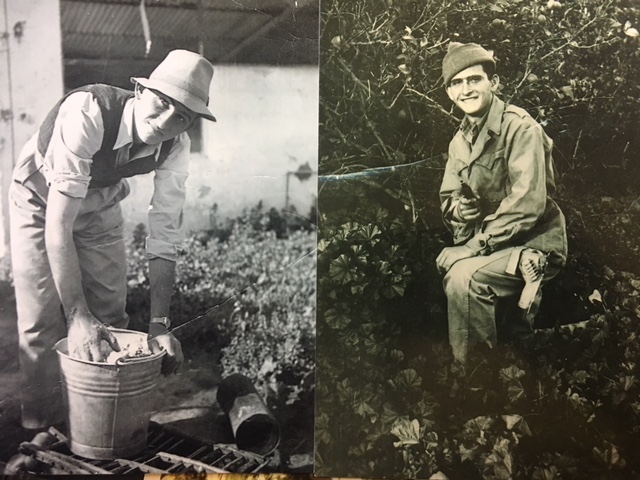

Questions asked by Amy Yelin in bold, answers by Gershon Yelin. Photos courtesy of Amy Yelin. Thanks very much to the Yelin family for sharing their Danzig experience. Were you born in Danzig? No. My mother went to Warsaw to give birth to me, in 1928. Our family lived in Danzig though, until I was about nine. Everything was German there, except for the post office, which was under Polish control. You had your choice when it came to money—you could use German or Polish currency. Can you tell me about your family and life as a child in the Free City? Altogether there were five of us. There was my father, Josef; my mother, Hava or Eva; my two older brothers, Joshua and Moshe; my two sisters, Lea and Luba; and me, the baby. Later on, two cousins came to live with us as well after their mother died—Adek and another Moshe—their last name was Rosenthal. It never felt crowded in our apartment though. I remember the laundry hanging about, and I remember my mother was always shopping and cooking and cleaning. She was always very busy. Sometimes I couldn't sleep because she was chopping away in the kitchen. What did she make? Chicken soup, gefilte fish—not like the American version. She'd bake all kinds of cakes, apple strudel. Oh, that was good. She'd get goose for the Sabbath. And my oldest brother—sometimes she made a big pan of this strudel and he'd almost finish it and then he'd say he didn't. She was always very busy. My mother was also very proud of the fact that she and [former Israeli Prime Minister David] Ben Gurion went to school together. They were both from Plonsk. Her father, my grandfather, was a rabbi, and he went out one day and never came back. I don't know what he died from, but her mother raised her alone. Then her brother died too young, and his name was Gershon, so I got the name. Moses, in the Bible, had a son named Gershom—Ger = alien; Shom = there—to remind him and other Jews who left Egypt in the Exodus. Tell me about your father. My father ran his own wholesale fruit and vegetable business in Danzig [the records say it was at Altstaedtischer Graben 21a from 1928 to 1939]. I remember his business had a cart for deliveries, and sometimes I would go around with the driver, who was very nice. I think the horse's name was Max. My father also traveled around Europe a lot for work. He'd get all dressed up in suits and would take this antique watch with him that he kept on a gold chain. Men used to also have these things that they would put around their ankle too—spats? Like what soldiers had. He had a walking cane too, not because he needed it, but it was because it was part of the wardrobe then. And he smoked cigarettes. But he especially liked snuff, tobacco that you could inhale. He kept it in a fancy antique silver box and he'd pull it out of his pocket and take a little bit to sniff and then he'd sneeze. Do you know how your parents met? I'm not sure. I would bet it was through a matchmaker. What do you remember about your religious life in Danzig? I remember my mother and I used to go to the Great Synagogue every Friday night. And I would see one of my teachers from school there, Samuel Echt. He would be all dressed up in these nice suits and hats—I remember a top hat—and he got to sit in a nice seat, like a seat of honor. My mother would be praying but I would just be staring at him thinking, That's what God must look like. [laughs] But that's all gone now. The synagogue was demolished by the Nazis. Decades later, the most amazing thing happened, though, when I saw Mr. Echt in in the Bronx in New York in the 1970s. We were both so happy to see the other had survived the war; both he and his wife had. It was funny too because I always thought he was such a giant and he was actually very small. I heard that he and his wife were able to get out of Danzig and go to England- that they accompanied 40 or 50 children out of Danzig to safety. What do you remember about Mr. Echt as a teacher? Oh, he was the greatest teacher. I remember one day he asked us all to write something … and I wrote about the trees outside the window—how some leaves which were blooming, and others were not. He got all excited and explained that the ones that were blooming were blooming because they were getting sun. Although he didn't dress as fancy at school as he did at synagogue, he would still be well dressed, wearing a suit. I remember him holding his daughter on his knees at school. She would grow up to be a nurse; and she was the one I ran into first, in the Bronx, and put me in touch with her father. Going back to the Great Synagogue, did your father and your siblings go too? Or just you and your mom? Just us. My father went to a different synagogue in Danzig. A simpler one—he didn't like the fancy synagogue. He just wanted to pray and talk to people. He liked it. My siblings didn't attend; they were interested in other things. Did you get along with your siblings? I was the baby so I had a good relationship with everyone. Sometimes my older brothers fought about political matters. One was right wing, representing the Israeli government; the other was left wing. So they'd have real fights. Sometimes they didn't talk to each other and I would have to deliver messages between them. What language did you speak in Danzig? German was my first language. I spoke a little Yiddish too. I didn't speak Polish … but my older brothers did. They used it when they didn't want me to understand what they were saying. When did you learn English? In school … probably in Israel. English was one of the three official languages there—Hebrew, Arabic, and English. Every sign was in all three languages. Was this a happy time in your life … in Danzig? Well, I think I was too young to understand what was really going on at the time in terms of anti-Semitism. Only later would I understand. In Danzig, my first school was a Christian nursery school. Everyone seemed OK. I even got Christmas presents! Once my mother was late to pick me up and a teacher was holding me on her lap. She was so nice. But then suddenly I had to switch to an all-Jewish school—and I wasn't sure why. I didn't understand anything was wrong about this. I liked that I got to take a tram to school. One thing I'll never forget was when a Jewish teacher, a gym teacher at the new school, suddenly started pounding on his chest while screaming, "I will defend this German Reich with my chest!" over and over. It was strange. But there were many good times as a child. I remember, not long before we left for good, going to see the circus in Danzig, and we got to drive these cars that you could hit the other cars with [bumper cars] and I saw my very first television in Danzig, in a store window. I'll never forget it … maybe it was just for military purposes. And I remember going to Shirley Temple's movies; I just loved her. What else do you recall about anti-Semitism then? Well, I didn't recognize it as that at the time. When I saw the Nazis march in the street as a kid I thought, Oh how beautiful—the music, and marching. They would sing songs about how 'the Jewish blood will drip from knives. …" I just liked the tunes and the thud of their boots as they hit the pavement. They beat up communists, and I remember the police came and they threw the people who had gotten beaten up into what looked these big laundry baskets, and they carried them away. Probably took them to prison. The communists were still trying to stop the Nazis then. But they were helpless. Honestly, for a while, the anti-Semitism didn't really phase me. But then, suddenly, we couldn't go to the beach in the German areas anymore. There were signs up: No Jews Allowed. My mother started to get worried, but my father not as much. My mother started dressing me in lederhosen, so I might blend in better. I remember she used to say, "If you're Jewish, you suffer." One afternoon, a group of Nazi youth followed me home after school. I remember they were calling me names and threatening me. I don't know where I got the courage, but I spit in the leader's face … and then I ran like hell until I made it home! [laughs] I still consider this my life's greatest triumph. I couldn't fight the actual Nazis, but this was like my own little war. What about friends? Oh, I had this little German friend. I used to visit him … he had such toys. He used to tell me that the man who was there, his "so-called" father was not really his father. He would tell me that his real father died on the Titanic. He probably didn't know who his father was. They lived in this little basement apartment. We were good friends. And there were other friends at school. In another memory, I'm running around on somebody's roof playing war—it was fun but then one kid got shot in the eye by a BB gun. He lost his eye. And I remember sledding … with Jewish and non-Jewish friends; it didn't matter then. Also, and this must have been later, I recall running over to a river with some friends to see these big German ships that were there. It may have been pretty close to the war starting. So when did your family finally leave? Well, if it were not for my mother, we might never have left Danzig and we might all be dead. She read a lot of history books, and she was aware that the world wasn't a safe place. That it never was, and that we lived in the middle of this German/Nazi atmosphere in Danzig. My father was in denial though, thinking "they're not going to touch me; I'm a good citizen. I have friends in high places." And I guess, after you build up a business, make a good life, it's hard to give it up. It was '38 when we left. I was in my classroom at the all-Jewish school and my brother Joshua came to take me out of school and he brought me to the train station. He told me my parents would meet me at the end of the train ride, in Warsaw. I didn't know at the time that the Nazis had come to arrest my father, and my mother had sent him a telegram—he'd been traveling on business around Europe—telling him not to come home. She told him she would meet him in Warsaw. I learned later that the Gestapo did come to the apartment and ended up confiscating everything—money, my father's business, everything in the house. Were you scared on the train by yourself? I wasn't scared—the people were nice. They offered me candy. And my mother was there waiting for me when the train arrived. We stayed with relatives in Warsaw. Eventually, maybe six months later, my parents and I left on a ship via Romania to Palestine. We were fortunate because my father had money and he was able to secure immigration certificates from the King of England to get to Palestine. My sister Lea and brother Moshe were already there; both of them had left for Palestine in 1935. Lea went to study in an agricultural school in Nahal, based on a kibbutz. Moshe went to Tel Hai, the kibbutz founded by Trumpledor. My sister Luba would never make it out of Europe—she would only get as far as Warsaw. She was supposed to go to school in Jerusalem to study the humanities, but some official made a decision to revoke her acceptance for someone deemed "in greater need" in Germany. The last time I saw her was when I was waving goodbye to her at the train station in Warsaw, when we were leaving to go with my parents to the ship in Romania. I remember she was crying and I was thinking, Why is she crying? We are going to this beautiful country with sunshine and orange groves. I can still see it like it was yesterday. So that was the last time you saw her? Yes. She died at Auschwitz, which we heard via an old boyfriend of hers from Danzig who had fought for the American army. He found some documents about her deportation to Auschwitz. Why couldn't she go with you on the train to Romania? I think it was because you had to be under age 18. What do you remember about your sister Luba? She was very beautiful. And kind. She had lots of friends. I remember one friend in Danzig who was named Anya. I also remember she was generous. When it was my birthday, she made me a cake. And she I remember she gave my mother a blue vase once—I think for Mother's Day. What happened with your brother Joshua? He would eventually make it to Palestine on a ship, the Parita, in 1939. He came in the middle of the night, after jumping off the boat and swimming to shore, and surprised us by arriving at our door. It was a happy reunion. |