|

|

|

49°05' N 19°37'

Translation of the

“Liptovsky Svaty Mikulas” chapter from

Pinkas Hakehillot Slovakia

Edited by Yehoshua Robert Buchler and Ruth Shashak

Published by Yad Vashem

Published in Jerusalem, 2003

Acknowledgments

Project Coordinator

Our sincere appreciation to Yad Vashem

This is a translation from: Pinkas Hakehillot Slovakia: Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, Slovakia,

Edited by Yehoshua Robert Buchler and Ruth Shashak, published by Yad Vashem, Jerusalem.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

[Page 302]

Translated by Madeleine Isenberg

Hungarian: Liptószentmiklós; In Jewish sources: Mikulas.

District Capital of Liptov and economic center in northern Slovakia

| Year | Number of Residents |

Jews | By Percent |

| 1727 | -- | 45 | -- |

| 1746 | -- | 131 | -- |

| 1784 | 952- | 77 families | -- |

| 1828 | 1,708 | 801 | 46.9 |

| 1880 | 2,811 | 1,115 | 39.7 |

| 1900 | 2,993 | 983 | 32.8 |

| 1919 | 5,400 | 1.033 | 19.1 |

| 1930 | 6,855 | 902 | 13.2 |

| 1940 | 6.402 | 957 | 15.0 |

| 1948 | 5,872 | 336 | 5.7 |

Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš was mentioned in documents dating from 1286 as the property of the Pongrac Counts. In the 14th century it received the status of a town and permission to hold market days and fairs. In time it became the economic center of a large area, with lively trade and workshops whose products captured the provincial markets. Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš excelled especially from its tanning industry, renowned throughout the kingdom[1]. In 1677 Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš became the district capital of Liptov, administration and government offices were opened, and manufacturing developed. Most of the residents at that time were Slovaks, a few Czechs, and they belonged to the Evangelical and Catholic churches. Many of them made their living from supplying goods and services to the people in that locale.

In the 19th century Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš was one of the centers of National Slovak movement and the location of several associations for the dissemination of Slovak culture. At the same time many schools were opened, books and journals were published on various subjects written in the Slovak language. The educational structure and the town's cultural life were influenced greatly by Slovakian intellectuals and from some of the leaders of the National Slovak movement who were born in Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš and continued to be active there. Among these people were M. M. Hodža[i], the Stodola brothers, the Bella brothers, the great writer Jesenský, and others.

In the 1870s Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš was connected to the important railway system leading to an industrialization process that resulted in rapid demographic growth. Alongside the tanning workshops that brought prosperity and renown, a chemical plant was built, a distillery, a textile factory and a few small enterprises.

During the period of the Czechoslovak Republic, Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš kept its position as an economic, cultural and administrative center for the Liptov area. During the period of the Slovakian State during World War II, pockets of resistance crystallized against the pro-Nazi rule. On August 28, 1944, partisans entered Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš and held it for a few weeks and set up their regional headquarters there. After the town fell into the hands of the Nazis, the rebels retreated to the forests that surrounded the town and continued to fight the Germans. On April 4, 1945, the Soviet and Czechoslovak armies liberated Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš.

About the History of the Community

The first Jews settled in Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš at the beginning of the 18th century. Most of them were merchants from the Holešov community in Moravia, who maintained commercial relations with the owners of the town, Count Pongrac. Count Pongrac granted his sponsorship to the Jews, and for a tidy sum rented them houses and businesses in the town center. In the first census of Jews in the area in 1727, 13…

[Page 303]

…Jewish families were counted (38 people) who were residents of Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš. Jewish merchants and peddlers flocked to the markets and big fairs that were held in the town and many of them eventually settled there.

The local nobility that benefitted from the sponsorship fees paid by the Jews, regarded their settlement there favorably. Even the population of Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš willingly opened the gates of the town to them, since the Jews filled an important role in the cultural growth of the town. They merited the freedom to participate in widespread economic activities and saw reward in their efforts and the kehila (community) grew and flourished. Among the Jews were some great merchants who developed trade relations that branched out throughout the kingdom, and exported leather and fine leather goods.

In the beginning, the Jews of Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš belonged to the kehila of Hološev and paid their dues to it. In 1728, Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš established its own independent kehila, having a prayer room in a private home and a ritual mikvah (ritual purification bath). It's possible that in that same year the cemetery was opened and the chevra kadisha (burial society) established, although one source indicates that the Jews of Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš acquired the land for the cemetery and synagogue only in 1730. In 1731, and possibly a little before then, the first synagogue was built in the Huštak neighborhood, where most of the Jews lived, built in the style of the old synagogues in Moravia. In the same period the Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš kehila served as the religious and organizational center for the Jews in the Liptov and Turiec districts. By the end of the 1730s, 17 Jewish families were living there and in the 1740s their number grew to 29 families, most of the families having migrated from Moravia. The head of the kehila was the Parnas[ii], Moshe DAVID, who also represented the Jews of the area to the authorities. Rabbi Pinchas LEIBEL served as the prayer leader and instructed the members of community in the subjects of halacha (laws) and religion. The children of the kehila learned in a cheder (religious school) from two “melamdim” (teachers) who were employed by the kehila.

From the middle of the 18th century, a rabbi served as the leader of Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš, Rabbi Moshe the Cohen, who the Jews called “our teacher and rabbi[iii].” In Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš, Rabbi Moshe founded a Talmud Torah (religious school) to which students from all northern Slovakia gathered. After him (1772-1813) the leader was Rabbi Yehuda Leib KUNITZ, who was among the important rabbis of his generation, and who increased the prestige of the Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš community and its reputation. In 1776, Rabbi KUNITZ opened a yeshiva, one of the first on Slovakian soil, in which more than 50 students studied. During his leadership the synagogue was renovated and expanded, a new cemetery was opened and additional community institutions were established. The head of the community at that time, the wealthy merchant, Mr. Mordechai Ber (“Rabbi Mordechai, the Prince”) represented the district's Jews to the authorities and merited great honor.

The Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš kehila reached the apex of its flowering in the years 1820-1830, under the leadership of Rabbi Eliezer LOEW, who was among the luminaries of his generation, and the author of the question and answer book, Shemen Rokeach. At his installation ceremony leading representatives of the towns, district leaders, and many locals attended. Rabbi Eliezer administered a famous and great yeshiva with more than 100 young men, and resulted in scholars of the…

[Page 304]

…first order. During the period of his leadership Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš became one of the important Torah centers in Hungary. In the latter part of the 1820s a dispute arose between the rabbi and the Parnasim of the kehila over the opening of a basic Jewish school. The rabbi opposed the idea completely and after his opinion was not accepted by the kehila, he left Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš. Several of his descendents were well-known rabbis in different places. In the early 1830s, the seat of the rabbinate was taken by Yissachar Bar MIKULAS (d. 1861), author of Minchat Ani, who is named after the town of his birth. He also earned a reputation for his acuteness. In the 1880s, Rabbi Zeev Wolf SINGER was the leading rabbi of Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš.

|

|

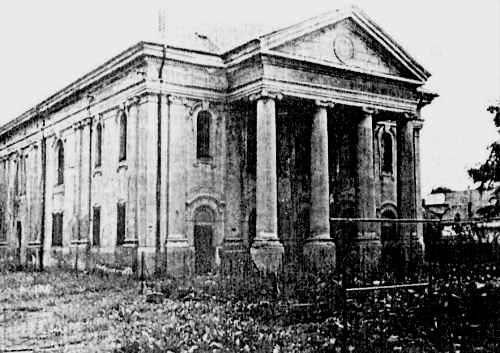

| Figure 1: Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš Synagogue |

In 1843 during the construction of the new synagogue, a controversy arose regarding the location of the bimah[iv]. The episode created waves in Slovakia and three well-known rabbinic arbiters were called upon to settle the dispute: Rabbi S. Y. L. RAPPOPORT[v] of Prague, Rabbi S. D. LUZATTO[vi] of Padua, and Rabbi Nathan ADLER of London. They established that it was appropriate to act according to the majority decision of the kehila. Following their decision, the bimah was moved to the front of the synagogue, the same as the custom of the renovators, despite the warnings and pleadings of Rabbi Bar MIKULAS, and despite the verdict of the orthodox rabbinical court that deemed the synagogue unsuitable. The beautiful new synagogue, the first of its kind on Slovakian soil, was built in the classic style at a cost of 100,000 Florins. At its dedication, representatives of the kingdom, town officials, and a large crowd of Jews and non-Jews participated.

In the 1848-1849 revolution, most of the Jews supported the Hungarian rebels. After the suppression of the revolution, a sum of 20,000 Florins was levied against the Jews of Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš; the sum was collected by the kehila's Parnasim and handed over to the authorities. In 1851, part of this sum was returned to the kehila and used to start a fund to care for education and culture.

The kehila of Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš was well organized in all its institutions. Alongside it, many organizations and groups acted for their welfare and mutual aid – “Bikur Cholim” (visiting the sick; established at the beginning of the 19th century); “Agudat Nashim Yehudiot” (Jewish Women's Association; established in 1845) that supplied a soup kitchen; the societies of “Halanat Orchim” (providing accommodations for travelers) and “Gemilut Chasadim” (free loan). In the second half of the 19th century the following were established: A Jewish hospital, a savings bank, Association of Jewish Young Women, Jewish Socialist Society, Clothing the Poor, Charitable Workers, and the cultural association, “Zion”.

From time to time conflicts and disputes broke out between the orthodox and the many enlightened who favored changes in the way of life and the way services were conducted in the synagogue. Some of the “enlightened” preachers employed by the kehila to side with the rabbi and dayan (judge) instituted revisions to the worship service that were not always accepted by the community. One of the preachers, Rav David LOEWENSTEIN, conducted a marriage in the synagogue that was not according to the traditional practices, a revision that aroused strong opposition from the rabbi and anger from a large part of the community. Dissatisfaction within the orthodox community continued to grow and in 1864, several families broke away from the kehila and established a separate framework for public prayer, headed by Rabbi Dov-Ber BENATH[vii] and the Parnas, Moshe STARK. Sometime later the breakaways set up their own separate community institutions and opened their own basic school that in addition to general studies subjects taught advanced Jewish studies.

In the Jewish Congress held in Budapest (1868-69), Moritz DINAR, head of the Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš kehila, represented the districts of Liptov, Turiec, and Orava. After the split of the kehilot, the Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš kehila joined the Neolog movement. The orthodox established a separate kehila. In 1875, the two factions reunited and joined the organization of Status Quo kehilot. The regulations of the kehila were approved anew in 1870[viii].

In the great fire of 1887, the great synagogue and additional communal buildings were damaged. The synagogue was refurbished and enlarged (its size was 22 x 40 meters), its façade was beautified and became one of the most beautiful synagogues in Slovakia. Near it a spacious community center was built that had offices, an auditorium, library, accommodations for the rabbi and sexton, butcher shops and abattoir. The kehila and Chevra Kadisha partnered in maintaining an old-age home and soup kitchen.

Jews of Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš placed great importance on educating children and the kehila's educational institutions earned a good reputation. In the beginning of the 19th century it became common among the enlightened families to employ private tutors from Czechoslovakia and Moravia. At the beginning of the 1830s a private Jewish school was opened in the town under the administration of Jacob UNGAR, with the language of instruction in German. A while later, an additional school was opened, headed by the teacher Moritz MAUKSCH. The DINAR family, whose son headed the kehila for many years, financially supported these private educational institutions.

In 1845 the kehila opened a four-year Oberschule (a high school), first in German and later also in Hungarian. The widespread fame of its high level of study attracted students from afar and even some non-Jews. Among its administrators were the preacher Rav David LOEWENSTEIN and Dr. KUBAK, who edited and published a Hebrew journal, “Yeshurun.” 10 Years later, in 1885, the Jewish school received official recognition, and in the same year, 351 students (128 of them girls) studied there. In 1869, it had six years of schooling, nine teachers, with 117 boys and 120 girls.

In 1860, a Jewish Reali[2] high school was opened under the administration of Dr. Adolf FRIEDMAN that lasted about 15 years…

[Page 305]

…and was the only one of its kind in northern Slovakia. Non-Jews also studied there. In 1900 the Parnasim of the kehila requested the opening a state-sponsored Jewish high school in the town and the chevra kadisha budgeted 250,000 Florins from its account, but members of the Catholic Church headed by Bishop Andrei Hlinka thwarted the program. Established in the town was a reading club founded by the young people, and later in 1845, a club for self-education.

Relations between Jews and the other inhabitants of the town were good and the Jews were involved in community life even before they were granted the rights of Hungarian citizenship. In 1865, the Parnas Yitzchak DINAR was elected as mayor of the town and was the first Jew in the Hungarian kingdom to carry this role. His service lasted until 1872. After him, Joseph STERN, Moritz RING, and Dr. Emanuel STEINER were elected to this highest office. Another Jew, V. FRIEDMAN, was among the heads of the Firemen's Association in the town. William SCHICK, from among the teachers in the Jewish basic school, was chosen to be the district supervisor of schools. Prior to the First World War, a Jewish drama circle was established in the town, putting on performances for the general audience in German, Slovak, and Hungarian. Many of the Jews in the town were educated and practiced the free professions.

Jews of Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš fulfilled important roles in the town's economy, and a few were among the pioneers of local industry. In 1890, M. STRAUSS set up a textile factory, P. STARK set up an alcohol refinery and a power station that supplied electricity to large sections of the town. Jews also owned several large tanneries, and most of the commercial businesses in the town.

Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš was the birthplace of many well-known Jewish personalities: Benjamin Zeev BACHER (Wilhelm BACHER, 1850-1913), professor of Judaica and administrator of the Rabbinical Seminary in Budapest, who also wrote many books; the poet and translator, Rabbi Simon BACHER (1823-1891) who translated holy writ into German and Hungarian; Rabbi Dov (Bernat) KULBACH (1866-1944), professor of Jewish wisdom and Judaica for the Rabbinical Seminary in Budapest and Rabbi in several important Hungarian kehilot; Journalist Albert STRUM; Judge Simon GOLDSTEIN, who was the first Jewish lawyer in Hungary; and publisher Samuel FISCHER (1859-1934), who lived from 1881 in Berlin and established the important publishing house, Fischer-Verlag, that still exists.

During the First World War, dozens of Jews from Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš served in the Austro-Hungarian army. 22 fell in battle and after the war a memorial was erected in their memory in the Jewish cemetery.

Jews between the Two World Wars

On 25th May 1919 a largely-attended gathering was held in Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš with representatives from many kehilot in Slovakia. At the conference discussion involved the question of the legal status of Slovakian Jewry, in light of the political and territorial changes…

|

|

| Figure 2: Children in Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš's Jewish School in the play “Cinderella.” |

[Page 306]

…having taken place in the country following World War I.

After the war the kehila of Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš had 382 tax-paying heads of households and its yearly budget was 220,000 Kronen. From that amount they budgeted for the upkeep of the synagogue and other communal buildings, for the cultural functions, education, and assistance to the needy. A significant expense comprised the salaries of 10 full-time workers and several temporaries. The head of the kehila was Albert STARK, and in the 1920s this task was filled by Rudolf STEIN, for several successive terms. Rabbi Zeev Wolf SINGER continued as rabbinical leader and was assisted by the dayan (judge) and moreh tsedek (justice teacher), Rabbi Adolf DEUTSCH. The kehila had two

|

|

| Figure 3: Samuel Fischer, native of Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš, one of the great publishers in Germany |

synagogues, a mikvah, a community center with an assembly hall and a library, apartments for “sacred vessels”[3], butcher shops, abattoir, and two cemeteries – old and new. The budget for welfare and relief served primarily to support accommodations for travelers, soup kitchens, and an old-age home. Those who worked within the welfare and relief projects included the chevra kadisha and societies such as the “Jewish Women's Organization” (headed by Rebbitzen SINGER), “Jewish Welfare Society” and others. The kehila supported a Talmud Torah and a basic 5-year school, with its instruction in Slovak. Leopold FISCHER administered the school and the heads of the school council were Rabbi SINGER and Dr. Julius HAKSNER.

In 1928 the Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš kehila joined with the “Yeshurun” liberal kehilot. Rabbi SINGER died in 1930 and after him there were no rabbis in Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš. Dayan Adolf DEUTSCH served in place of a rabbi. In the 1930s a small Orthodox group conducted separate prayers but was not officially recognized as a kehila.

During the Czech Republic Jewish involvement increased in the life of the town and local society and in the 1920s they had six seats in the town council. Jews also worked in public administration, some even at senior levels. Emil NEUMAN served as town treasurer and Rabbi Zeev SINGER was a member of the town's education committee. Dr. Albert KOKAS served as district physician, Dr. Nathan SCHLESINGER served as the main public notary, and engineer Alexander FODOR was the administrator of public works for the Liptov District.

In the 1930 census only 368 out of 902 Jews listed themselves as Jewish for their nationality; the rest defined themselves as Slovaks or Germans. The National Jewish Party had great support in the town. The head of the local branch, Dr. Mati WEINER, was a leading member of the Jewish National Party in Czechoslovakia. In the 1928 municipal elections the Jewish National Party received more than 400 votes (16% of the total), similar to the number of votes for the “Slovak National Party” and both of them were the largest parties in the town. Four representatives of the Jewish National Party sat on the town council. In the 1930s the Jewish National Party retained its numerical strength.

Zionist activity also reached its peak in the same years, and the Zionists also left their mark on the cultural and communal life. The Zionist Association in Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš, headed by Isidor STRAUSS, was among the biggest and most active in Slovakia, and the branch of WIZO[ix] in the town comprised hundreds of women who participated in a variety of social activities. In 1929, Jews of Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš donated 4,000 Kronen to plant a forest in Israel named for T.G. Masaryk[x], President of Czechoslovakia.

The Maccabi Sports Association, founded in Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš in 1919, maintained an exercise hall, tennis courts and football field, and hundreds of young people and adults were members there. Most of the young generation were members in Zionist youth movements. In 1922, a branch of Hashomer Kadima (the Forward Guard) (which later became Hashomer Hatsair the Young Guard) was established, followed by ”Maccabi Hatzair” (Young Maccabi) and “Bnei Akiva” (Sons of Akiva). These youth movements in the town had their own clubs. The “Youth Circle for Self-Education” and “Zionist Association” conducted lively cultural activities in the Zionist spirit.

[Page 307]

Below are the data on the sale of “shekalim”[xi] in Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš toward the Zionist Congresses:

| The Congress | “Shekalim” |

| 15th (1927) | 320 |

| 17th (1931) | 250 |

| 20th (1937) | 585 |

| 21st (1939) | 260 |

During this period the weight of the Jews in the local economy grew especially in business, production, and banking affairs. The economic situation for Jews in Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš was good and most of the businesses in the town were owned by them. Among the Jews, 12 were industrialists, 81 were merchants, 25 tradesmen, four out of seven were doctors, six out of seven were lawyers, a veterinarian, some engineers, and la large number of clerks, in both public and private practice.

Jews were owners of several large and medium-size enterprises: in leather, a fertilizer and chemicals factory, a liquor and strong drinks plant, an alcohol refinery, a cheese factory, and a “lending bank for the Liptov district” under the management of Philip STARK.

The licenses issued by the local business office in 1921 demonstrate the distribution and variety of Jewish owned businesses in the town:

| Type of Business | Number of Businesses |

Jewish- owned Businesses |

| Taverns & Restaurants | 22 | 19 |

| Grocery | 21 | 17 |

| Fabric and Clothing | 16 | 14 |

| Leather and Shoes | 14 | 9 |

| General and Haberdashery shops | 9 | 7 |

| Agencies | 9 | 9 |

| Strong Liquors | 6 | 4 |

| Wood, Heating & Building Materials | 5 | 5 |

| Freight (or transport) | 4 | 4 |

| Building Contractors | 4 | 2 |

| Watches and Jewelry | 3 | 1 |

| Agricultural Products | 3 | 2 |

| Small Enterprises | 3 | 2 |

| Other | 11 | 8 |

The Holocaust Period

With the establishment of the Slovak Republic on 14 March 1939, the kehila numbered 325 heads of households. The dayan Rabbi Adolf DEUTSCH continued in his position as a substitute for the chief rabbi. Heading the kehila was Dr. Mati WEINER, from among the Jewish community leaders in Slovakia, and from 1940, the head of the “Jewish Center” for the Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš district. On the 12 and 13th of May 1940, the National Conference of World Zionists in Slovakia was opened in Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš, the last before the Holocaust.

During 1940 economic restrictions were imposed on the Jews. Jewish children were rejected from the town's high school. And the kehila opened a Jewish middle school. In 1941, under the instructions of the authorities, dozens of Jewish business establishments with returns of less than 30 million Kronen were closed. About 40 large enterprises and some factories with yearly returns of approximately 45 million Kronen were turned over to the arizators[xii]. In August 1941, dozens of Jews who were discharged from their former businesses were sent to camps for hard labor. In the fall of 1941, 540 Jews who were deported from Bratislava (q.v.) were brought to Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš and the number of Jews in Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš reached its highest with more than 1500 souls. The refugees had nothing with them and they received aid from the kehila and the “Jewish Center.” On November 4, 1941, dozens of villagers broke into the synagogue, broke furniture and destroyed books and holy artifacts. Afterward they broke into Jewish homes and damaged their property.

At the beginning of 1942, on the eve of deportations, there were 1605 Jews in the town and its surroundings. At the end of March 1942, 120 young men and women were rounded up in the town's district government building. The young women were sent to the transit camp in Poprad (q.v.) and from there, at the beginning of April they joined the transport to Auschwitz. The young men were taken to the Zilina (q.v.) collection camp and from there sent to the Majdanek camp near Lublin, Poland. Mass deportations of families began on April 2, 1942, and in its process, 596 Jews from Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš and its surroundings were rounded up and sent with the transport to the Lublin area. After the Nazis performed their selections, able-bodied men were sent to the Majdanek work camp, while women with children and the elderly were sent to the Sobibor extermination camp. On October 11, 1942, some more local families were sent to the Zilina camp, after the authorities rejected their exemption permits. In the wave of deportations of 1942, about half (49%) of the Jews of Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš and the surroundings were sent to extermination camps, a small percentage compared to other places in Slovakia. It would seem that this was due to the satisfactory relations that existed in the past between the Jews and the rest of the town's population.

After the deportations, 76 Jewish families remained in the town – comprising 250 souls – who still held exemption permits and their deportation was deferred. In the whole district 623 Jews remained. The kehila reorganized under the leadership of Mati WEINER, and Martin SCHWARTZ served as the secretary of the kehila. In 1943, after the death of the dayan Rabbi Adolf …

[Page 308]

DEUTSCH, his role as rabbi-substitute was filled by Max GRUENBERG, and Herman LEIBOWITZ served as chazan (cantor). In the Jewish school, under the administration of Armin WEISS, studies continued until the end of June 1944. At the beginning of 1944, about 300 Jews still lived in Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš and in the whole district lived about 690 Jews who had exemption permits.

In May 1944 some dozens of Jewish families settled in Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš who were evacuated from eastern Slovakia and many other Jewish refugees gathered in the town when the Slovak rebellion broke out. On the eve of the German occupation, many succeeded in fleeing to the forests or remote villages, where they found refuge until the end of the war.

Post-War

After liberation, about 350 Jews returned from the forests or Slovak villages. At the initiative of Rabbi Yitzchak ALBOIM the life of the kehila was renewed. The old cemetery had been destroyed during the war, but the synagogue and newer cemetery were cleaned and quickly refurbished and returned to use. Even the Zionist branch returned to work and at its head was Dr. A. TEICHNER. In 1947, Jews of the town donated 115,000 Kronen to the Keren Kayemet fund to plant “Forest for the Czechoslovakian Martyrs” in the hills of Jerusalem. The “Young Maccabi” youth movement also renewed its activities. In 1948, 336 Jews lived in the town, and after 1949, when many Jews either immigrated to Israel or other countries, 242 Jews remained. In the new cemetery, memorial plaques were set in place to the memory of the victims of the Holocaust and to the 12 members of the kehila who fell as fighters during the Slovak rebellion.

The synagogue served the kehila until 1953 and afterward was converted to a warehouse. The kehila continued until the 1980s, and the public prayer was held in an improvised prayer room; the cemetery was in use until then and the school, the mikvah, and community building remained in their places. In the 1990s, a few Jewish families still lived in Liptovský Svätý Mikulaš. Finally, the great synagogue was renovated and it serves for cultural events.

References

Yad Vashem Archives, M48/649-688, 1765; M5/57, 82, 110, 114, JM/11011-11016, 11018-11019, 11026, 11 036Footnotes

ŠÚASR, MV: 1939-1945/550

Greenwald, Toysent Yahr Judisch Leben, pp. 221-222

Cohen, Khakhmei Hungaria (Hungarian Sages), p.36 and on

Bárkány-Dojè, pp. 287-292.

MHJ, vols. III, VII, XVI, XVII

S. Kovaèevièová, Liptovsky Svatý Mikuláš, Liptovský Mikuláš 1992

E. Kupèák, Liptovský Mikuláš 1268 -1968, Bratislava 1974

Lanyi, Bekelfy-Popper, Szlovenskoi zsido, pp. 179-219

Allgemeine Judische Zeitung, 18.2,1938

Haderech, no. 19 (1940)

Selbswehr, no. 53 (1929), 38 (1930)

|

|

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 21 Jul 2022 by LA