|

|

[Page 323]

[Page 324]

|

|

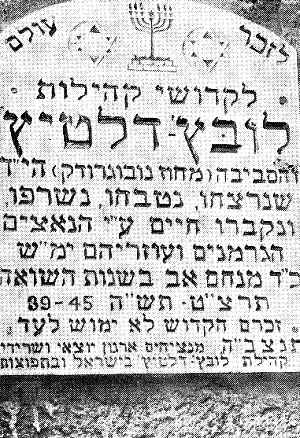

| Translation of the Plaque: In eternal memory of the martyrs of the Lubtch-Delatitch community and the environs (Novogrudek District), may the Lord avenge their blood, who were murdered, slaughtered, burnt and buried alive by the German Nazis and their willing aides, may their names be obliterated. 24 Menachem Av in the years of the Holocaust 5699 - 5705 (1939-45) Their holy memory will never be forgotten. May they rest in peace! Perpetuators of their names: The organization of the Lubtch-Delatitch landsmen and survivors in Israel and the Diaspora |

by Yitzchak Berliner

Translated from the Yiddish by Harvey Spitzer z”l

| And not only Warsaw - the city of martyrs - the bloody crown of Poland. Lublin and Lodz and Grodno, Bialystok and Krakow, Lemberg, Vilna as well. Through every stumbling path and road of our home the slaughterer spread about, fanning his sword in murder and did not cease killing.

The last voices - up on high - knocked

I will not distort my weary face |

From the book, “Shtil Zol Zayn” 1947

|

|

by Natan Yankelevitch, of blessed memory

Translated from the Hebrew by Ann Belinsky

|

|

of blessed memory |

Confusion reigned among the inhabitants of the town when the news went around that the Russians had “liberated” the western districts of occupied Poland and were approaching the town. People hurried to store food for the hard days to come. The Byelarussian representative, Ragola, organized propaganda in favor of the new regime, but he failed in this - when he said that although there was a lack of clothing and shoes in Russia…and thus he was exiled from Lubtch by the occupying forces.

The Russians arrested all those who were suspected of opposition to the Soviet regime. Many were exiled, mainly people of property, all the shops and commercial businesses were nationalized. They organized administrative institutions and an employment bureau where the jobless were registered and were then placed in suitable work.

The Jews worked mainly in clothes and shoe workshops, and whoever was not a craftsman was given clerical work. In the town there was a regional storehouse for agricultural produce, mostly grain and flax. I worked in this storehouse with Mr. Zochobitzky from the town of Mir, the son-in-law of Avraham Rabinovitz. The chief bookkeeper was Moshe Persky.

They learnt Russian language and literature in the school. The synagogues were turned into storehouses, but the Russian Orthodox church was left untouched. The gentiles continued to pray as if there were no change.

The inhabitants of the town elected a council with 24 members to whom people turned with requests and claims, and they negotiated with the authorities.

No hostile relationship was felt towards the Jews, but there was great sensitivity towards the question of loyalty to the regime. When it was found out that I had a brother in the United States, I was immediately fired from my work, received an identity card for a period of only 3 months: this meant that I could be sent away from the area.

The Russians remained in the area for one year and nine months until the Germans betrayed them (1939). When the rumors came that the German army was approaching, the Soviet command began to flee in panic. Despite the news about the German atrocities, the Jewish public of the town didn't believe the rumors, and thus the Jews stayed there and didn't flee.

Akiva Baksht fled - because he was a teacher of the Russian language and was scared of the German authorities. He got as far as Nigorloya , but it was already impossible to cross over the previous border, and he was forced to return as he had come.

In the meanwhile, the German government based itself in the in place with the help of the Christian inhabitants of the town. Akiva was caught and handed over to the Gestapo in the nearby town of Ivye, where he was executed by hanging in the market square.

The Germans permitted the Christian population to loot Jewish property, and there immediately began a pogrom which lasted 24 hours. The gentiles went crazy - they damaged and destroyed and looted everything they could get their hands on. They searched for hiding places where valuables had been hidden, smashed windows, tore down doors, emptied houses of their chattels and foodstuffs. Houses remained open to all, without windows or doors. Houses of Jews in the neighboring settlements were also looted and burgled.

There were Jews who had given their property to the Christians in the area for safekeeping from the peasants, but when they asked for it back, they were not answered and were sent away with blows and threats.

Part of the town was burnt, mainly because of the bombing. Houses were burnt on Fish Street, Kapucheva Street and part of Castle Street. There were Jews who removed their property to the fields for fear of fire, but the gentiles stole it there.

The inhabitants of the town worked for the wealthy landlord in gathering grain and their payment was in grain. Workshops were also opened and people worked there mainly in repairs.

Two weeks after the Germans occupied the place, all the men were ordered to clean the streets of the town. During the time of work, a group of Germans arrived, including a number of local gentiles and said they needed 40 workers. Among those taken were the brothers Yekutiel (Kusha) and Avraham Soltz. Their father, R' Yaakov Soltz, asked the Germans why they had been taken and the answer was that they also needed a translator. R' Yaakov volunteered to work as the translator. The whole group was liquidated and no one knows how.

When I heard that men were being taken to work, I slipped away to a field and hid within the standing grain.

In response to the request of the German commander, twelve people were chosen for the job of “Judenraat” (Jewish Council). Yaakov-Chaim Leibovitch was chosen as chairman of the “Mossad” and his deputy was Chaim Bruk. The “Judenraat” was obligated to carry out all orders of the German commander.

According to the demands of the Germans, groups of Jews were sent to work in the forests and in preparing bricks from peat. For this work, the “Judenraat” received bread and milk, which they distributed amongst all the populace.

An order was issued requiring all Jews to go into the Ghetto and wear the yellow patch on their chest and back- for identification. Anyone disobeying was shot on the spot.

Three hundred Jews were taken to a work camp at Dvoretch: the people left on foot. Those who had difficulty walking were put onto wagons. We arrived at Horodtzena where we slept in the local school building.

Two brothers who complained of stomachaches were shot on the spot. The next day we continued on foot to Dvoretch. In the work camp we worked at quarrying stones which were transferred to the Front for building strongholds. The Germans “paid” the “Judenraat” for their work and the “Judenraat”, in turn, had to provide us with food.

We worked in Dvoretch until the spring. Our “Judenraat” managed to free some of the craftsmen from the camp and return them to the town, as well as some family heads with children - I was included amongst them. Those that remained in Dvoretch were annihilated to the last person.

A report reached us that there had been an “Aktion” in Novogrudek- that it to say that the Jews had been executed. Aharon Brezinsky, together with another Jew whose name I don't remember, went to Novogrudek to verify what had happened. On the way, they went into a flour mill, but the Jewish miller was no longer there: the Germans caught them both and shot them on the spot.

The inhabitants of the towns of Ibynitz, Derbena, Nelybok and Rovzvitch were brought to the Lubtch ghetto. Their children stayed in the village and were murdered. All who were sick or had difficulty walking- were killed.

The decrees multiplied and became worse. Jewish blood became cheaper and cheaper. The Jews were persecuted and destroyed for amusement and from boredom. Many were tortured to death.

A tiny few of the Jews of our town managed to be saved.

The holy community of Lubtch and its Jews are no more…

“Yitgadal veyitkadash” - May His Great Name become exalted and be sanctified.

|

|

by Yisrael-Gershon (Yisrol) Yankelevitch

Translated from the Yiddish by Harvey Spitzer z”l

|

|

Poland, August 1939-Mobilization!

It was a hot summer's day when I received the order to report for duty in the Polish army to defend the “fatherland” against the armies of the Nazis, who decided to swallow up their good partner in anti-Semitism and rule over the whole world.

Two weeks later I was already back in my town among my family. The Polish army suffered a bloody defeat and ceased to exist. The Polish government collapsed and the German murderers were already acting with savageness, sharpening their claws against the defenseless Polish Jews.

Three days after my coming home, the Soviets occupied our region. We breathed a little more freely, thinking that the war was over for us.

There followed twenty months of adjustment to the new regime which, with its “solutions”, impoverished the entire population- the Jews in the towns and the peasants in the village, who were forcibly collectivized in the newly established “kolkhoze” or collectivized farms.

These were also months of clenching one's fist and gnashing one's teeth out of grief and pain, helplessly watching the enormous train convoys which supplied the German armies- continuing their bloody march across Europe- with raw materials and food which were desperately needed by the half starved and raggedly clothed population of the great Soviet country.

There again came a lovely, bright sunny day, June 22, 1941, on which the Germans paid back its Communist supplier of goods with war, death and destruction. Another mobilization and another order to report for military service. That same day, they began to concentrate all those called up for army duty, Jews and Gentiles from the whole region, on the grounds of the castle in Lubtch. We stayed there until Monday, June 23. At 2:00pm, we were ordered to go home and await further instructions. No explanation was needed regarding the situation because all the Soviet officials soon began packing up, burning documents and fleeing in wild panic.

The next morning, Tuesday, at 10:00am, we heard the sound of motors. We noticed new airplanes coming from the direction of Delatitch. They circled around the town a few times, descended and began dropping bombs. The first bombs fell along the riverbank and killed a Gentile woman. A bomb fell on the saw-mill and another one hit the post office. A fire broke out and my house also burned down. I harnessed our horse, threw a few things salvaged from the fire into the wagon, seated my wife and child in the wagon, took along my father and brother, Yeshayahu David, and we went up to the meadow behind the synagogue. Nearly all the Jews in Lubtch had gathered there. There was a great panic: Adults and children were crying and screaming. Mothers hysterically looked for their lost children and fainted from fright. Husbands were looking for their wives and they were all running around together in total confusion, not knowing what to do.

Night fell, but people were afraid to return to their homes. Some of the Jews decided to go to the surrounding villages and hide in the homes of Gentiles they knew. I took my family and we went away towards Atchukevitch. I went up onto a field and decided to spend the night there, planning that at daybreak I would look for a familiar Gentile and hide in his house until the situation of the Jews in the town became clear.

The summery night did not last long. If it hadn't been for the fright and worry, it would have been a pleasant trip in the lap of nature. Everything around us was full of life and fresh juices: the grass and ears of grain covered with dew, various creatures and insects calling to each other in all kinds of voices and sounds. We didn't close an eye either out of worry and fear for the coming day. Only the baby slept peacefully with his small lips open, breathing in the clean air. From time to time he let out a sigh as most babies do in their sleep, but this tore our hearts and my wife would shed tears.

As soon as it got lighter, I noticed a group of Jews from Lubtch in the distance. I went over to them and asked why they weren't going to the Gentiles. They told me that the Gentiles did not let them cross their threshold and drove for fun to the Germans, “who would soon finish off the Jews”.

Moshe Tiktin, who was among the Jews in the group, said:

— Fellow Jews, there's no purpose in sitting any longer in the field. Our fate is sealed anyway. Let's go back and see what's happening in town.

In town, we noticed how the peasants from the entire district were robbing Jewish property, loading up full wagons and hurrying home in order to try to come a second time. Their faces were aflame, their eyes burning with a savage fire of hate and revenge. We immediately understood that Tiktin was right, our fate was sealed for destruction and death.

As my house was burned down, we went to live with Itche Tevies on Novaredke (Novogrudek) Street. Three days later, the Germans came and placed a force of the town's Gentile police all around. Boris Kunitzky was made the commander. His lieutenants were Kola Komornik and Petrik Bedoon who, all their lives, lived close to Jews, benefited from Jewish help, maintained good relations with Jews and during Soviet times were avid supporters of Communism. Now that they were given full authority over us, they exhibited their beastly hatred in the most brutal way.

The next day Kola Komornik came to the house. I was holding the baby in my arms. He came over to me, gave me a terrific smack in the back and ordered: — Bring your things here! I began to beg and plead, reminding him that he was my neighbor and that we always lived in peace and in friendship. He then shouted in German: — Damn Jew! He pulled off my jacket, stamped his feet and left.

A couple of days later, a few Germans came and gave the order for all Jews to come to the marketplace so a few men could be selected for work detail. None of the men wanted to go and hid, but the Germans came into the houses looking for them. I was lying in the attic, hidden in the hay. A German was standing on the ladder and asked my wife whether any Jews needed for work were hiding there. My wife answered that I had gone out to the market place and that no one was hiding and that if he wished, he could go up and look for himself. Apparently, her assured answer convinced him and he left. He then went into Blecher's house and brought out Layzer Shitzgal. In this way, they captured 51 men- the youngest and healthiest who were taken out of the town. One, two, three days went by and we heard and knew nothing as to what had happened to them and where they were. We tried to guess: One person said that they were working somewhere not far from the town and another said that they were taken away to Germany. Then a few weeks later we found out that they were taken to Novogrudek behind the barracks,-where they were all shot.

Four days went by and we were terrified to leave the house. They again took three Jews for work by the railroad tracks and shot them there. The three victims were Kushe Saltz, Simcha Chaimovitich, and Aharon (Ara) Berezinsky.

This was followed by a decree for all Jews to move into the ghetto. The entire Jewish community was squeezed into 27-30 houses, starting from Liova Levin's house as far as Yehoshua Yankel, the tailor's house including the synagogue. Three or four families were put into each house and it was impossible to move due to the tightness.

Every couple of days the Germans would come with the police and take out 40-50 people as if for “work”, and they would disappear without our knowing where. We would go into the synagogue, recite psalms, hold a fast, but nothing helped.

About six months after the Germans came into the town (I, unfortunately, don't remember the exact date), six hundred people were selected and were led away like sheep to a work camp at the Dvoretz station, not far from Novoyelnia. It was just the first night of Chanukah, 5702 (1941).

I spent one night in the camp and ran away the next day. They caught me, however, and the commander beat and warned me that if I ran away again, they would shoot me on the spot. But for me there was no difference between staying in the camp and being murdered or being caught and killed a few months earlier. I ran away, in fact, a second time and was not caught. I ran without stopping to Novoyelnia- a distance of six kilometers, which took me no more than twenty minutes.

In Novoyelnia, I found the “Jewish Council” from Lubtch. They had been in Dvoretz and were going back to Lubtch. These were Gershon Kapushchevsky, Shalom Ziman and Alter Chemes (Shmulevitch). I begged them to take me on their wagon, but they were afraid and advised me to walk separately, six or seven meters away from them.

That is how I reached the ghetto in Novogrudek, but the ghetto police did not let me enter and threatened to report me to the German commander. I hid in a corner on the side and that night I snuck into the ghetto. There I looked for my brother Beryl and wept. He gave me a piece of bread and I went out of the ghetto and headed for Lubtch. I managed to go all the way unnoticed by the Germans and Gentiles and safely reached the Lubtch ghetto to be with my wife and child.

The next day when the “Jewish Council” found out that I had come back to Lubtch, they decided that I had to return to Dvoretz. I declared that I would not go back and that they could do whatever they wanted with me. They explained that I was an extra person, not listed in the official papers and that I had to go back. This was to no avail as I refused to follow their advice. When they also threatened not to give me an allotment of bread, I began to act insolently - did I have another choice?- and said that they would indeed give me a portion of bread if they didn't want any trouble. In short, they fought with me for two full weeks and finally gave in. I don't blame them, God forbid, as I knew very well what would happen to them if the Germans found out about it.

On March 15, 1942, the Germans issued an order that the Jews could not keep cows or goats and that they must bring them to the marketplace and give them to the Gentiles. We remained without a single possession, hungry, torn apart and depressed, living corpses who already had nothing to lose in life.

On April 1, 1942, the “Jewish Council” received an order to supply 125 workers for duty in Novogrudek. I was also included in the group and we were sent on a small train to the ghetto in Novogrudek. We asked the district commissar to allow our wives and children to join us. He granted this request and four days later, they were already together with us. We did very hard work and received a daily allotment of 400 grams of bread. Meanwhile, news reached us that five hundred people were sent from the Lubtch ghetto to Shterben near Vorobievitch, where they were later brutally murdered. Only 150 people remained in the Lubtch ghetto. They were elderly and sick and not capable of working.

On the 24th day of Av 5702 (1942), the Germans carried out a mass slaughter. Thousands of Jews were killed that day including men, women and children from Lubtch, Delatitch, Neyshtot (Niegnievitch), Karelitch (Korelitz), Ivenietz, Zhetel, Derevna, Zholodok, Novoyelnia and Novogrudek. People ran around in panic, looking for a hiding place. Others offered the murderers money and gold which they gladly took and then drove them to their slaughter. My wife called out that if they took the child, she would go with him. I took her with me to the barracks, but we were separated there. That was the last I saw of my wife and child. Later, returning to the ghetto, I found their things, the last remembrance of my blood and flesh.

I also found both my brothers, Beryl and Yoske, in the barracks. Everyone was lined up in two rows surrounded by armed Germans and Estonians with machine guns. An SS officer stood by, holding a list. He called out the names of the people and pointed to the left or right. We didn't know which direction was for life and which for death. When they called out Yankelevitch, our family name, the three of us stepped to the right. A German grabbed hold of Yoske and began pulling him to the left. Yoske resisted and the German shot him on the spot before our very eyes. Fifteen people were similarly shot, including a few boys from Lubtch.

Of the more than 1,000 Jews who were at the barracks, 275 were selected and the others were shot the following day near the village of Litovke, A few days later we found little notes bearing the message: “Brothers and sisters, if you remain alive, avenge our death!” We were kept in a horse stable at the barracks for three days without food or water. At 8:00pm on Friday evening, the doors were opened and three Germans entered shouting “Heil Hitler!” We all got up from our places and remained standing with our heads bowed. They ordered us to leave the stable and stand by fours in a row with our hands raised. Each group of four was accompanied by two Germans with a machine gun. We were then ordered to march along Karelitch Street to the former Polish courthouse building. There about 1500 Jews, the remainder from all the surrounding ghettos, were driven together. They were all bitterly weeping and lamenting the loss of their closest ones. I went around in a daze, without any feeling, unable to speak or weep because my heart had completely turned to stone. The next day I saw Beryl, who had also lost his wife and children. We embraced each other and couldn't hold back our tears.

|

|

of the Jews massacred in Litovke near Novogrudek |

Some Germans entered and drove everyone outside. They then selected 150 men and seated them in trucks and sent them off to Smolensk for work. A couple of hours later, a group of 15 people, including myself, were selected and we were brought back to the town on Slonim Street. There we loaded 10 barrels of chlorine on a truck and we left for Litovka. They led us to a large, deep pit full of murdered Jews and ordered us to pour the chlorine into the pit and then pour sand over the pit. When we finished pouring sand over the pit, they brought us, the 15 men, to the empty ghetto. Entering a house, we heard human voices coming from under the floor. When we asked who was speaking, it suddenly got quiet. We put them at ease and told them they didn't have to be afraid of us because we were also Jews from the ghetto. Just then about 30 people crawled out of their hiding place, dirty, smeared all over and unrecognizable. Among this group were my sister's two children, five and seven years old, as well as Shalom Leibovitz's daughters, Shifra and Sonia. There were also some Jews from Lubtch and Karelitch. We took out two people who were already dead. In this way, a handful of people gathered together in the ghetto and we were again driven back to work. One day we, a group of 12 people including 2 women, did not go out to work. That afternoon, two Germans came and asked why we did not show up for work. I answered that we were sick and couldn't go to work. One German began shouting that he would soon make us healthy. He ordered us to stretch out on the ground and he beat us with a stick all over our bodies. The other German watched the spectacle and laughed. We screamed terribly from the pain until we remained lying there nearly in a faint. For two weeks we lay there unable to move a limb.

I decided to escape into the forest and I consulted with Beryl, Shlomo and his three children and a few more Jews from Karelitch and Derevna. The day we decided to run away from the ghetto, I didn't go out to work. I spent the whole day planning our escape. As the ghetto was guarded by policemen, we bought two liters of strong drink outside the ghetto and at 9:00 pm, one of the girls in our group offered the liqueur to the policemen. At the same time, when they were drunk, we went out of the ghetto through an opening in the fence which we had prepared during the day, and we began running. Some Gentiles noticed us and began shouting that the Jews were escaping from the ghetto. The police started shooting right away, bullets whistled around us, but we managed to run into the woods and out of the range of fire. It immediately became apparent that Shlomo's two daughters, Shifra and Sheine Rachel (Sonia), were not with us. Slonimsky and I went to look for them. We found them sitting on the side of the path, crying that they wanted to go back to the ghetto. I calmed them and said that being in the ghetto could not be worse at this point and that we might be lucky and find safety in the forest. I took them by the hand, like two small children, and brought them into our temporary hiding place.

We rested a little and then started out for Delatitch. We apparently lost our way and walked around the whole night until daybreak. We had to hide in the woods because walking on the roads during the day was a sure death for us. All of a sudden, shooting broke out in the woods. We lay down between thick shrubs so that we wouldn't be seen. That day, which was the Sabbath, was drawn out like a year. Even when the shooting stopped, we were afraid to make the slightest move. Only at nightfall, did we get up and leave. We went to the Neiman River and crossed over in a rowboat which we found on the shore. We were already on the other side of the river, walking a few hundred meters, when they again started shooting at us. We again started running until we got deeper into the woods. After resting for a quarter of an hour, we went to Komarovsky's house in the hamlet. Snow had just fallen and our footprints could be clearly seen in the snow. The peasant was afraid to keep us in his house and advised us to hide in the woods where we would be safer than among the peasants. He gave us some bread, butter and cheese and asked us to come back in the evening well after dark.

When we came back again late at night, he told us that the Germans and a few policemen had been at his house during the day, inquiring whether any Jews or partisans had been at his house. He naturally denied it, and they went away. He again gave us some food and advised us to go to Kluchist, a village near Nalibok.

We didn't have much choice. We set out in the direction he indicated. We got as far as Krasne-Horka and hid there. It was bitingly cold, we had no food and we didn't know any of the peasants in the surrounding hamlets. We stayed there one day, two days and ate up what little food we had. We were oppressed by hunger, and the cold was becoming unbearable. We decided to return closer to Lubtch, to Farbotke's house in the hamlet, a distance of about twenty kilometers.

When we came to the hamlet and knocked on the door, Farbotke asked who was knocking. When we answered that we were Jews from Lubtch, he was afraid to open. However, when he heard that it was Shalom Leibovitz and Yisrael-Gershon Yankelevitch, he opened the door. When he saw the state we were in, the honest peasant began to cry. We told him about our situation and asked for a little food. He gave us a bucket for cooking, bread, flour, salt and told us to go to the potato pit and take as many potatoes as we wanted. Loaded down with food, with a sack of potatoes, we came to our people in Krasne-Horka. We stayed there two weeks and then went closer to the village of Potashne. We dug out a dirt house and remained there six months until we met the partisans from Otriad, attacking the Germans in Stalin's name. I came into Otriad as a partisan and took part in many operations against the Germans, taking revenge for the innocent Jewish blood that was shed.

When the region was liberated in June, 1944, I returned to Lubtch and began to work in the town militia.

I was still fated to experience the good taste of sitting three and a half years in a Soviet prison and then three months in a Polish jail until, after so much suffering, I succeeded in reaching the welcoming shores of the Jewish homeland, the State of Israel.

by Velveke Yanson

(Volodshke The Machinegunner)

Translated from the Yiddish by Harvey Spitzer z”l

|

|

It's a warm day in August, 1939. People are strolling, laughing freely, enjoying the sunshine. That evening, a news report comes through that the Germans are preparing to attack Poland. There's a hubbub in the town. People whisper to one another, run to buy food and buy up whatever is left. The older Jews say that the Germans won't be worse than the Poles. One of them says that in the First World War nothing bad happened on the part of the Germans. A few days later we already hear that the Germans have issued an ultimatum to Poland. The country is frightened and trembles. The army reserves are called up. One annual set of soldiers leaves for the front, then another and so on. The “osadnikes” also get their turn to be sent to fight.

I go back home with a heavy heart as though we've been warned that a terrible storm is moving in our direction. We already hear that the Poles are fighting very heroically on the outskirts of Danzig but, unfortunately, after a short battle, the Germans are victorious. And we already see Polish soldiers running back, wounded. The Germans keep marching on ahead, taking city after city until they reach the Bug River, where they remain in position. The Russians occupy the eastern part of Poland in accordance with the Hitler-Stalin Non-Aggression Pact of 1939.

The Red Army Occupies White Russia

On September 17, 1939, we hear how the Red Army is taking city after city: Stoibtz, Baranovitch, Novogrudek. The Lubtch police force runs away. The Polish eagle is torn off the post office building and is replaced with a red flag.

On September 21, around four o'clock in the afternoon, the small train arrives, the red flag already flapping, but no soldiers are aboard. It's already dark in the town. We're all gathered on Castle Street next to Lipchin's soda shop, expecting the Red Army any minute. Around six o'clock, the town grows speechless, although we're all gathered in the streets, but no one can let out a word. We can hear the galloping of horses, and the wind carries singing in the distance. Everyone calls out: “The Red Army, the Red Army is coming!” The singing gets louder and louder and we notice a Cossack division of the Red Army singing the well-known partisan song: “Over hill and dale”. About 400 Cossacks come riding through and stop near the marketplace at the end of Castle Street. The whole town gathers around them. People ask questions and the soldiers are very polite. The division moves further on and life under the new rulers begins. The priest is arrested and then released. The study halls [synagogues] are closed and later serve as storerooms for crops. I go to see my aunt, Leahke Mendelevitch and my uncle, Baruch-Mordechai Yankelevitch, and we bemoan the situation.

A short time later, I leave for a job in Novogrudek. My mother and sister, Henia and Grunia, with her husband, David Pertchik, remained in Lubtch.

War Again

Time goes by in this way until June 22, 1941. Early in the morning, we hear the terrible news that the Germans have bombed Soviet cities, and it is reported on the radio that the Germans have suddenly attacked Russia and declared war. All cities are being bombed, and the next day Novogrudek is also hit; nearly half the town is destroyed and there are many casualties. The same day I receive an order to report for army duty. Lots of men are called up for military service, and we set out on our way deeper into Russia.

I wear a Russian uniform and hold a gun in my hand for the first time in my life, and the radio carries the news that the Germans are getting closer and closer. We finally reach Mogilev and the officer tells us that as soon as we cross the bridge, we'll join up with the Red Army and there we'll put a fierce resistance. Unfortunately, however, as soon as we crossed the bridge, the Germans, as though growing right out of the ground, began shooting heavily at us from all sides. We get an order to run away, whoever and wherever possible, just so that we can save ourselves, because we are surrounded. I run to a peasant's house, change my clothes and start going back towards Novogrudek. After several days of wandering, hungry and thirsty, I reach Novogrudek, where a ghetto in Pereshinke was awaiting me. All the Jews were already locked up in the ghetto. I was there until the first slaughter. The Germans selected Jews from a part of the ghetto and led them out like sheep to be shot. I am among those chosen. My instinct shouts to me: “Run away!” and I run under a hail of bullets. I manage to escape and run towards Lubtch.

Coming into Lubtch, I saw that all the Jews, here too, were already locked up in a ghetto. My mother, sister and other relatives were living in Moshe Yankelevitch's (Mayshke the Beer Maker's) house. After being there over a month, I was taken, together with other young people, back to Novogrudek. I was in the ghetto a second time. Months go by and the great slaughter takes place. Everyone is led to the barracks, but about one hundred young people are left in the ghetto, including myself. We are taken to the courthouse where we worked very hard for the Germans.

At the end of 1941, a peasant brought me a letter from my sister Grunia. She writes me that that they are being held in a barn in Vorobievitch, about five hundred people, including women and children. Among them are my mother, my sister Grunia, her husband David and their two small children. My younger sister Henia was taken to Dvoretz with all the young people because she was less than fifteen years old. Grunia writes that the Germans say that they will be taken to Baranovitch for work. I sent a letter back to her with the same peasant. Unfortunately, my letter never got to them as that very night the Germans poured gasoline over the barn and everyone was killed. The people were burned alive and their agonizing cries pierced the heavens. But the heavens were closed and bolted as though God Himself had turned away from us. Anyone who managed to get out of the barn alive was shot.

The next day, the same peasant came to me and brought me the “good news”. He wept while telling me what happened, but I stood there as if my heart had turned to stone, unable to cry. Later I began to tremble and jolt, and my shouts were like a lion's roar. Lying at night on the hard bench, a fire was kindled in my heart, a fire of revenge and I swore that my hands would not rest until I avenged the beastly death of those dearest to me, whose innocent lives were stolen from them.

I Escape

Four days go by and I decide to escape. The building in which we were locked up was encircled three ways. The first circle of guards consisted of Estonians, the second of Poles and the third of Germans. The building itself was surrounded by barbed wire. I must confide in someone. I asked him to assume my name after I escaped because ten people are shot as soon as person fails to answer to his name. He begged me not to do it because it meant a sure death - no one had ever escaped from there. There were three of us who wanted to escape. And just at the last minute, we took on a fourth, Chana Ribak's brother-in-law (David). Two nights later we cut through the barbed wire at a certain point. Everything was set and at one o'clock the next morning when the camp was asleep, we quietly went over to the prepared place. I said to them: “You go through. I'll go through last”.

At the same time, we had to time our escape as we had only two to three minutes to get through the fence before the guards passed by on their patrol. This was because the guards would walk towards one another and pass each other without meeting. We had to go quickly through the wire fence just at that time. There was an interval of only two to three minutes when the guards passed each other and were out of sight. I let them all go through and then it was my turn but, unfortunately, I got entangled in the barbed wire. At that very moment I saw the Estonian soldier approaching. I tore myself forcefully from the wire and, in so doing, cut my back and felt that my shoulders were bleeding. I stood up and met the Estonian face to face. There was no other way. Before he could manage to shoot or shout, I came at him with a knife. He threw down his gun out of fear. I hit him over head with a revolver which I smuggled out of the ghetto and dragged him to the spot which we had earlier agreed upon in a grove of trees about 250 meters from the camp. We all met there. We left the Estonian unconscious and went quickly away in order to reach a forest before dawn where we could hide all day. As we were running, we could hear the alarm and shooting in our direction, but it was already too late….

My Revenge as a Partisan

It took us a day and two nights to reach the vicinity of the town of Dvoretz. I wanted to see my sister Henia, who was being held in the camp. We lay hidden in the fields and saw how hard the children were working. Late at night, I made up my mind to go into the camp. I wondered where my sister was and went in. When she saw me, she couldn't stop crying and shaking. People asked me how I got into the camp and were worried that if I were caught, everyone in the camp would be shot. I therefore decided to leave that same night. My sister asked me to take her with me, but I myself didn't know where I was going. I promised that I would come back in about a week and surely take her along. It was hard to say goodbye, but we had no other choice.

We walked all night long and early in the morning reached the partisans of Orlianske's unit in the forests around Zshetel. They stop us, interrogate us and bring us into a dirt house. Jewish partisans question us, but they don't want to take us into their group and order us to go on further. Our question is “where”? So we again drag ourselves through the great forests until we reach the dense woods around Lipitchianska and get to the town of Duzshi-Volia by the Shtara River, not far from Slonim. We come to a group of partisans led by Vanushka (a Christian). This is worth emphasizing because the Jewish partisans sent us away, but the Christians accepted us. After a short period of training, we were placed in “Bulak's unit, consisting of about 320 fighters. I'm given a gun, which renews my strength and re-awakens the desire to take revenge. We fight against the bloody Germans every day.

So we attack the towns of Deretchin, Zshetel and surrounding villages where there were Germans. I take revenge, which gladdens my heart. Knowing, however, that the next bullet which flies in our direction can be the end of my life, I ask the commander to let me go and take my sister Henia out of the camp in Dvoretz. He grants me permission and sends five more partisans with me. We start out on horseback towards Dvoretz, a distance of 120-130 kilometers, but unfortunately, not far from the town, a peasant brings us the bitter news that the whole camp was annihilated just the day before. I become as wild as a lion in my thirst to take revenge against the Germans.

A few days later, the news reaches us that, during the night, Ukrainians and Germans tore into the village of Nakrishok, in the heart of the partisan area, captured the village, digging themselves in for a long stay in deep trenches. An order is received from the staff for all the partisan units to attack the village at daybreak. The village must be re-taken no matter what the cost in casualties. Our force consists of three thousand men, two tanks and three canons. Their force numbers about 1,200 men. We prepare with heavy armament. Around seven o'clock in the evening, we march out to the meeting point, half a kilometer from the village at the edge of the forest. We reach the point at dawn, one hour before the attack, which is due to take place at 6:00am.

We meet up with partisans from the surrounding villages. We are given the order to rest, to prepare the weapons, to be ready and not to move from the place. It is deathly quiet. There are heavy clouds in the sky and it is drizzling. We are told that the first shot of the cannon will be a sign that the attack has begun. The units spread out in three parts so that the village can be attacked from all sides. I'm very tired and fall asleep on the grass. For the first time since my mother was murdered, she comes to me in a dream and says: “My child, you are now going into a bitter fight with the Germans. I will stand by and ask God to protect you. Don't be afraid”.

All of a sudden a loud clap is heard - the attack has begun. With a great, resounding shout of “hurrah”, we run across a little river by the village mill. The enemy's bullets fly by from all sides and my comrades are falling on my right and left, but we keep running and shooting. I take up a position by the village well, set up my machinegun and keep shooting. Suddenly, I notice a German aiming his gun at me. A second later his bullet pierces my cap, burning the hair off my head. I fall down in a faint, but I can hear a nurse shouting to see whether I'm alive. I want to answer but cannot bring forth a word and nearly choke…

The doctor runs over to me. I hear him say: “A lucky person. The bullet only grazed the skin on his head. He will soon stand up.” Ten minutes later, I come to. The nurse is sitting over me, crying. She surely thought I was dead. Standing up, we start running on ahead, chasing after our partisans. The fighting goes on in full intensity. As I'm running, I remember my dream and just at that moment I notice the German who shot at me. I run closer to him and he keeps shooting at me, but my thirst for revenge is stronger and quicker than he is. Now I'm almost right on top of him. I shoot an entire round of 72 bullets at him and take his gun, his things and boots. I come back to my group, throwing myself further into the battle. An hour later, with the arrival of Orlanske's unit, the village is re-taken. Over six hundred dead and seriously wounded are lying about. Eighty partisans have fallen. We return to our bases. I'm called to headquarters and because of services rendered, they appoint me commander of sixty partisans.

End of 1942

We hear that the German forces are concentrating around the dense woods where we are hiding, and people say there will be a great chase. A week goes by until it is reported from headquarters that about 100,000 German soldiers are going to clear out the forests. They encircle the woods on all sides. We take up our position on one side of the Shtare River and the Germans on the other. Only one direction is left free in case we have to retreat. It's already the end of November, 1942. They open fire with great cannons, and a battle ensues. Our forces number about 80,000 partisans. We also have tanks, cannons and mine launchers, but not too many. We've already been fighting for two days and nights. I lie with my group in a trench at the river's edge. We are ordered not to let the Germans get through from our side. It's very early in the morning on the third day. The Germans open up with great fire, using their mine launchers. There are four of us in my little trench: I, a young fellow from Zshetel, who serves by preparing bullets for the machine gun, a Russian partisan and Chayke, the nurse from Deretchin. In the midst of the shooting, when I'm very busy concentrating on the enemy, the Russian shouts out that he's been wounded. I call out to Chayke that she should help him, but there is no answer at all from her. When the shooting subsides a bit, I get up and go over to Chayke who, unfortunately, is lying motionless. It appears that she's been dead for quite a while. Leaning against the dirt wall, she was frozen. She was barely 17 years old….

We fight another day and night until they finally begin their general attack. During the night, the Germans try to cross the river six times, but we push them back with many losses. We let them swim halfway across the river and then open fire with all the weapons in our possession. Around 3:00 AM, they start shooting into the forest from all sides. There is no place to put up a resistance. Everything is burning around us. Just then we hear that Doctor Atlas and many commanders have fallen. We receive an order to run away- whoever can and wherever possible-and to re-group later. The Germans press on further into the forest. We meet up with thousands of partisans who are running in our direction. The ground is actually burning around us. Hundreds of partisans are lying dead or wounded.

I run through deep mud with a small group of six people, but we meet Germans and shooting ensues. We manage to get away and reach the Orlanske units. However, when we meet up with them, they are also running away. There is simply no safe place for us. Itche Levine from Novogrudek says to me: “Let's go to the “family” groups.” This was a group of Jews who were hiding without guns some 25 kilometers from us. Wet, hungry, exhausted, we finally reach them. It was quieter there, but I come down with typhoid fever and they're sure I'm going to die. Several good acquaintances take care of me. They nurse me back to health with boiled water and pieces of dry bread. Russian partisans arrive. They encircle us and say we'll be shot because we're deserters. We plead with them and assure them that we're going straight to our units.

We leave, but I can't stand on my feet any more. With great exertion, we finally reach Orlanske's units. We again join the combat ranks. The Germans are still on the roads but with smaller forces. The whole army has already gone away. The fight against the enemy is renewed in a manner favorable to the partisans. However, anti-Semitism is now rampant. Wherever we go, we see murdered Jews - men, women and children. This is the work of the Russian partisans. It is intolerable to us as Jews and a fire burns in out hearts. Meanwhile, we leave to attack the town of Zshetel, where we fight all day long but fail to achieve our goal and must retreat. Our two cannons get stuck in the mud. More Jews are sent-under a hail of bullets - to pull them out of the mud. We thus lose half of our comrades. We get back to our base tired and depressed. Other Jews are sent to guard the few tanks which are in our possession.

Lying there exhausted, we hear a loud explosion- the tanks with the Jewish boys have blown up by accident. This is already enough for us. We choose a special group of Jewish partisans led by Senke (a young Jewish man from Minsk). We talk about taking the best guns. We ask permission from the head commander, as we want to go for food. He allows us to leave and there are now three different groups. We all go out in various directions, but we speak quietly among ourselves about where to meet. Early the next morning, we meet around the forests near Komink.

Our forces unite with Senke at the head and I as his lieutenant. We're about fifty people, all well armed. We do the same to the Russian partisans that they did to our Jews. We kill every one who wants to come to us. Senke, our commander, who can't speak any Yiddish, says that his grandmother once told him when he was a child that it is written in the Jewish Bible that one must take an eye for an eye. Three months go by in this way. The Gentile partisans speak in fear about Jewish bandits going around killing them in revenge for their acts. They are in pursuit of us. Getting to us, however, is very difficult because we maintain a double watch, each of which is a kilometer apart and besides, we never stay in the same place. We're divided into two groups.

A terrible misfortune, however, occurs. We were once in two houses, I with Senke and other comrades in one house, and the rest in the other house. We were very tired after a hard night. It happened that one of the guards fell asleep and was stabbed to death. The Russian partisans who are searching for us sneak into a house and kill the whole group of eighteen people. They would certainly have put up a fight, but were, unfortunately, all asleep and never woke up.

Everyone is also asleep in our house. Only Senke and I are sitting at the table and eating, and four other comrades are sitting and chatting. Suddenly, about sixteen Gentile partisans break into our house with their guns aimed at us and with grenades in their hands, because they knew that they could never take us alive. Senke throws me my machine gun and, grabbing his own, manages to shout: “Fire!” At that moment, a bullet hits him in the forehead and he falls on me. Shooting breaks out, and our lives are in danger. They thought that our men were shooting at them from outside. A panic breaks out among them. Our comrades who were asleep were all shot and the owner of the house, a Christian, and his daughter are killed. There are only sixteen of us left. Our guns are taken away, and an official reads aloud a written note stating that we are sentenced to death by shooting on account of the criminal acts which we committed. Many Jews have already been killed in this way, but our lives are spared on condition that we leave the district. We request permission to bury our comrades.

Everyone is set free, but the commander goes over to me with another partisan. He orders him to take me into the neighboring woods and shoot me because I was Senke's lieutenant. The commander leaves and nothing less than a miracle occurs at that moment: The partisan, who was supposed to shoot me, gives me a terrible smack. Having nothing to lose, I grab him and lift him up to stab him, but he shouts out to me: in Russian: “Be quiet! I'm also a Jew.” I become confused, knowing that there are no more Jews in Vanke's unit. He leads me into the woods, fires his gun several times, kisses me and says: “Go with God's help. Maybe we'll meet again sometime.” He was the “political manager” of Vanke's unit. To this very day I don't know his name.

After a night of wandering, I meet up with our surviving comrades. But where do we go without guns and food? And we have great wounds in our hearts, having lost so many dead comrades, but there's nothing we can do about it. I muster up my courage. I find an old case from a revolver in my knapsack. I stuff it with straw, so that it will look like a real revolver. We go into the house of the first peasant we encounter and order him to give everyone food and to provide us with a horse and sleigh as well. At the start, he's unwilling to listen and starts laughing, but when I take hold of my straw revolver and give him ten minutes to get everything ready and if he refuses, I'll shoot him and his family and we'll burn down his house, he then furnishes us with everything.

Winter 1943

We reach the thick woods around Lipitchianska. We hope to join up with our units, but we find out that we are being sought all over as deserters and that we'll be shot immediately if we just show our faces. We must go back quickly. We leave again for Orlanske's units. The time is still turbulent and I am among a group of Gentiles. I'm weak and sick, but one must not mention that one is ill. Meanwhile, a group is organized to bring provisions. We set out on a very cold night. We come close to hamlets. I go as a lookout, and the others are lying in wait by the road. A few people come towards us. It's very hard to see and we call out: “What's the secret password?” That night the password was “Stalin”. They answer correctly and we're sure they are also partisans. When we approach them, we see that they are not our men, but we didn't know for certain because they were wearing civilian clothing. As a Jew, I noticed that they had on Jewish coats. We ask where the others are. They answer: “In the hamlet”. We order them to go ahead and we keep our guns aimed at them the whole time. We enter a cottage.

There, in the darkness, we see that the house is encircled by many people, but we don't know who they are. However, when the door is opened, we notice Estonians and Lithuanians. A high-ranking German officer is in the house. They begin questioning us, but we pretend not to understand. The German orders them to shoot us at 6:00 am. To make sure that we won't escape, they strip us. We sit there naked, like newborn babies. The German officer leaves the house. Only three Estonians remain to guard us. The clock on the wall strikes every hour and the time of our death draws near. I tell my Russians what's going to happen. We talk together and decide that when they take us out early in the morning, we should all run off in different directions. Fate will show who is destined to remain alive.

It's nearly six o'clock. Four Lithuanians come in wearing large furs. We are ordered to stand up and we're told that we're going to be brought to another house, but we realize that this isn't correct. We're naked and it's terribly cold on the street. We know that our end has come…. Certain that we won't try to escape, they keep their guns on their shoulders. The door is opened and we're ordered to go. I go out first and take my first step on the snow with bare feet. The snow sticks to my feet and I see red stars in the sky. The pain is indescribable, but we want to escape from the murderous hands. We give a signal and run in different directions. The forest is about 150 meters away. I start running towards the forest, but in a zigzag. Before the Lithuanians manage to take their guns off their shoulders and heavy furs, I'm already in the forest. A few minutes later I hear shooting on all sides. I hear one of our men shouting “God” and that's all. No other words are spoken. I'm sure that both Russians are already dead. I run like a deer and can no longer feel my feet as I'm completely frozen. From afar, I see the house of the guard who watches over the forest. I run towards it, knock on the door with the last of my strength. The door opens, the heat from the house strikes me in the head and I fall down in a faint on the threshold.

Late in the evening, the Christian man tells me that when I fainted, he forced open my mouth and poured in a full glass of spirits and wrapped my feet in a cloth with pig fat because I had no more skin left on my feet. He placed me on the oven and I slept there until late at night. I open my eyes and, as in a dream, am presented with scenes of everything that happened to me. I know that I was taken out to be shot, and here I am lying on an oven. I want to get down, but my feet are like pieces of wood, and I can't feel them at all. I call out: “Who is here”? No one answers. A few minutes later, the Christian man comes in carrying wood. He tells me what happened to me. I lie there for two weeks and he heals my feet. Later he gives me slippers so that it would be easier for me to walk and he sends me away with God's help.

The partisans in our unit already know that all three of their comrades were shot. We've already been long forgotten. I return as a grown man with a beard, in slippers and torn clothes, and no one recognizes me. But a few minutes later, they come over to me, touch me and can't believe that I'm alive. I'm promoted to the rank of commander and put in charge of a group of 72 partisans.

A few months go by and the anti-Semitism among the partisans becomes more and more virulent. It once happens that I'm going on a mission with the group and they're talking among themselves: “If we catch a Jew, we'll cut him into pieces; on account of them, we have to sit in the forests.” I must emphasize that my group consists only of Russians and they don't know that I'm Jewish. They only know that my name is Volodshke. This sinks into my mind and I think: If the Germans don't kill me, my own partisans will. We secretly meet with all the comrades who remained alive from Senke's group and we decide to go away from there.

September, 1943: We're a group of more that 20 Jews with Nonia Shelubski at the head. We appoint him to be our leader. We meet together with Tuvia Bielski, who asks us to join his unit. We tell him that we'd like to combine forces, but that we should be a separate group. This idea, however, isn't acceptable to Tuvia, and we remain apart. The Germans are again hunting down Jews. They are already now in the dense woods around Nalibok. We are near Huta. I'm now serving as a lookout. The men in Bielski's unit are running away, whoever can manage to leave and wherever it's possible to go. I come riding on horseback to a group which had not yet managed to run away. The men are crying and say that everyone has already escaped, but they themselves don't know where to go. In our group, however, we all stayed together. We weren't to take anyone into the group or separate ourselves from the group. But seeing that the people in the group didn't know what to do (the group consisted of members of the Druk family now living in Montreal, Yisrael Bezshovski, now a resident of Tel Aviv and another branch of the family in Warsaw), I decided to lead them to a safer place. It's also important to point out that there was a daughter, Lilke, in Bezshovski's family. Lilke is now my wife and we have three daughters and a son.

And so, I was with them for a few lovely months. When everything quieted down, I again join my former group and we again negotiate with Tuvia Bielski. We combine our forces but remain a separate group.

We get more comrades from Bielski's unit and we organize a unit bearing the name “Orzshenikizshe” Our unit becomes the strongest force within Bielski's unit. Bielski has a very good reputation in the area because of our undertakings. We blow up trains, roads, bridges, everything which can serve the Germans. I, too, belong to the group that carries out actions with explosives. And another member is my good friend, Leibush Ferdman, who now makes his home in Newfoundland, Canada.

1944

A year of fighting the Germans and carrying out actions with explosives has gone by. Good news reaches us that the Red Army is driving back the Germans with great losses. We encounter Germans and win many battles, taking many prisoners who are given the same kind of death that they gave our loved ones. They beg us to let them live, promising they'll do everything for us. Each one claims he is not guilty, but our hearts are as hard as stone. We have only one answer: “May their memory be erased”!

Things go on in this way until September, 1944. An order is received from headquarters that the Germans are retreating in haste, the Red Army is pursuing them, they will have to pass through our district and therefore we must dig in and strengthen our forces so that the Germans cannot get through. We are ordered either to capture or destroy them. Women and children are taken to a safer place. Men alone remain to strengthen our forces. Older men dig trenches and get the guns ready, while the young people take up positions, stand on guard and even perform double guard duty. Everything must be ready so that we can confront and annihilate the enemy.

As I am a machinegunner, I take six comrades with me and we take up a position opposite Zorin's unit. Nearby is Benjamin Dombrovski, also a machinegunner, with six fighters. During the day we can hear shooting in the distance, and at night the shooting is closer. From time to time, Germans appear, but no sooner are they noticed than they are wiped out.

A few days go by in this way and the enemy attempts to break through our lines. The Germans are unsuccessful, however, because our forces are very strong, not only our own, but there are more and more Gentile units behind us. Finally, the decisive day comes. We are all lying in our places at dawn, expecting the worst. The Germans realize that there is no way out. The Red Army is pursuing them from behind and we are positioned in front of them in a great force to prevent them from getting through our territory. Lying there in hiding, we notice that, from afar, they look like flies, as there are so many of them in number. Thousands and thousands of Germans are preparing to attack us, shouting wildly. We receive an order not to move from the place.

My lookout is sitting up in a tree. He's a Jew from Stoiptz in his early fifties. He shouts to me: “Open fire, the Germans are here!” But we wait for an order to attack when they get closer.

Suddenly, thousands of Germans spring up, as if from under the ground, engage in battle, overrunning our positions all along an area of four kilometers. A terrible battle ensues, a life and death struggle, and I fire my machinegun without stopping. I can see how dozens of Germans are falling from my bullets. My machinegun is hot, but there's no time to stop. The battle goes on for four hours. Hundreds of Germans lie dead. They fall, but fresh soldiers are sent in to replace them, one after the other. Just at that moment, a large group of Germans overrun my position and shout: “Put down your gun!” And I shout back: “Put down your guns!” I tear off the ring from a hand grenade which I'm ready to explode rather than fall into their hands. A comrade from my left flank hurls a grenade and starts shooting with his automatic gun. Only eight wounded Germans remain out of the thirty something who attacked our position. We also lost many fighters and many were wounded.

However, we have no time to lose. Since they cannot break through our side, the Germans storm Bielski's camp. They succeed but suffer many casualties. Bielski also loses many partisans. Breaking through the camp, they meet up with the partisans of the “Stalin” unit, who wipe them out. Thousands of enemy dead already lie about. The battle goes on for eight hours. Our front becomes quieter and we're busy caring for the wounded and burying our dead comrades.

We return to our camp where we also find dozens of dead fighters. My wife thought that I was no longer alive. I was terribly exhausted and thirsty, without water a whole day. She simply didn't recognize me. The next day we meet up with the Red Army. Our joy is indescribable. We are finally free after so many years…

The Red Army goes on ahead. We remain in the forest for another few weeks and then march into Novogrudek. My wife, her family and I leave for Lida.

In 1945, my wife and I move to Minsk, where I receive a medal for distinguished service.

Later, I went to Bialystok by myself, where I'm arrested by Polish soldiers as a deserter! There is much more to mention, but it's hard to recall all the details.

In Bialystok, I rejoin my wife and her family and we move on to Lodz. With the fall of Berlin, we go on to Prague, Budapest, Leipzig and later to Gruglaska-Tarina, where we were in a refugee camp until we were able to emigrate to Canada in 1949.

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Lyubcha & Delyatichi, Belarus

Lyubcha & Delyatichi, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 18 Mar 2013 by LA