|

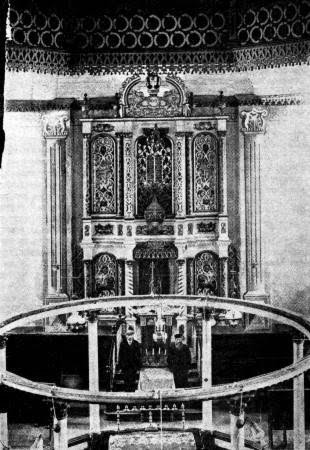

Standing on the bima at the right is the shames [synagogue sexton];

on the left is the gabe [trustee of a public institution]

|

|

[Page 39]

by D. R.

Translated by Jerrold Landau

The first tannery in Krynki was set up already around 1864. Other smaller ones followed in its wake. As Avraham Miller relates, the “wet” tannery only worked with cattle hides – for shoes, straps, awnings, carriages, etc. These products were sold inside the city itself on the market day. That morning, the tanner would take all of his products, tie them with ropes to the “broken vessel” of the small wagon, and hitch himself to it. His wife and children accompanied him, following behind him, to help push it forward as it went up the hill. He arranged his meager “merchandise” next to the wooden pen of a merchant, and stood next to it to wait for a “trader,” that is, a customer from the villages who would come to the market, and who might purchase some of the leather to make for himself a pair of plaited sandals (that were common among the farmers). During that time, the all the family members of the tanner guarded the wagon, so that no small thing would be stolen, for in those days, even minute, torn piece of leather would serve as a “purchase” for a poor farmer.

From these lowly, shaky tanneries, the Krynki leather manufacturing sector developed, which later became well-known for its volume and quality of its products.

This was during the 1860s. At the beginning of the 1860s, the serf farmers in Russia were liberated – a period of change for that empire at the beginning of industrialization. The Czarist regime even related in a positive fashion to the new economic situation. As we have noted, the tendency to ward manufacturing was already felt among the Jews in the Grodno-Białystok region during the 1820s. It found its expression in Krynki as well with the beginning of the textile manufacture.

The move toward tanning work in Krynki involved not only a willingness to engage in manual labor, even as a day laborer, but also involved overcoming of the revulsion regarding work that was unpleasant in the literal sense of the term, especially with the “wet” work with cattle hides (“carcasses”) before they were dried – with the working of the “repulsive” [material] (that was also considered a “disgrace”) and even damaging to health, especially given the sanitary conditions of those days in particular. Nevertheless, the difficulties with livelihood and the economic sense of the Jews of Krynki had their effect. Thus did the tanning sector grow in the town with the passage of time.

This happened even though Krynki was, from a geographical perspective, a remote place on the map of Jewish settlements in the area. It was far from both the water routes and the land highways, and it had no railroad at all. Despite this, it was blessed with an abundance of high-quality water flowing toward it from the wellsprings and from the artesian wells that were dug later on. Furthermore, it is told that one day, salty chemicals were found in those waters – minerals that are important for the tanning work and that improve the products.

A tanner, one of the pioneers of this work in Krynki, would work himself, and also employ some Tatars from the area. He would purchase raw hide “at a discount” from a flayer of carcasses or a butcher. He would process it into a coarse product and sell it to a shoemaker, or to a purchaser from the villages on the market day for fixing boots. The tanner would barely earn a meager livelihood from this.

The first workers in the factories in the “wet” work were, as we noted, Tatars and their wives. After some time, they also included Christian villagers.

[Page 40]

Germans worked in the “dry” work, for they were pioneers of tanning of horse hides (“Hamburger” hides) in Russia. Jews learned from the Germans until they became specialized in this field and themselves became expert tradespeople. Such tradespeople were even in demand outside of Krynki.

Hide processing quickly spread throughout the entire town, until the government changed its mind and stopped granting permits for setting up “wet” tanneries in the center of the settlement due to the inferior sanitary conditions. After a great deal of effort, the manufacturers later succeeded in receiving permits to open enterprises for the processing of hides on the other side of the river in the fields of “Janta” where the manufacturers obtained large areas and built giant tanneries. These had large windows and very comfortable equipment, such as concrete tubs and the like. There, they processed horse hides for various products, and employed hundreds of workers, tradespeople, and apprentices. Some of these factories became known not only by the Jews of Krynki, but also by many villages of the area.

Ab[raham] Miller

Translated by Judie Goldstein

Chapter on Textile Production

Before the leather industry arrived in Krynki, the shtetl had been busy for sixty years in the previous century [18th c.] with cloth production. In stables and in attics – stood (weaving) looms. Back and forth they ran without cease. Big and small, everyone worked. From morning until night the noise was heard and the clatter of the machines together with the singing of the bobbins. I still remember the old song that the young women would sing:

“Mama, arrange a marriage and give meA weaver was popular. He earned six to seven rubles a week while other artisans, for example a shoemaker or a tailor, earned more like eighteen gulden in the same time and not able to make ends meet.

A man, a weaver;

The day after the wedding I will travel

In a carriage with rubber wheels”.

The weavers had trouble with their hands. So before the spinning they used the strength of the waterfall from the big and small Nietupe and a little water helped with the task. There were also a lot of “roundabouts” (an arrangement using the strength of a horse, also used later in the leather factories to pound bark). Cloth production quickly developed and several fortunate manufacturers built steam factories with high chimneys. Krinik was noisy. The whistle of the steam factories and noise of the modern machines left its mark on the shtetl of an industrial center.

I would like to mention some of the manufacturers. It is thanks to them that Krynki reached its high status and they also bore the usual shtetl names: Yehusha Kugel's, Zundel Ite's, Mordchai Meyer Katsemakh, Meyer Yokhe's, Moshe Abraham the Wealthy, Munye the Tanner, Berl Pukh, Yidl Eli Chatskel's, Boruch David, Moshe Slava's, Yosel from Dobra-Valke, Chaim Jankel Hersh's, Hersl Sukenik, Yosel Tsalel Enya Kresh's, Jankel Moshe Abrham's, chaim Eli, Berl. Chaim Jankel's, Moshe Chaim Jankels, Feyvel the Ekideker, Moshe Yoshitser, Gdaliya Krupnik, etc.

[Page 41]

Besides the manufacturers, there arose in the shtetl a class of big merchants of raw material, commissioners and wagon drivers (there was no railroad in Krynki at the time).

Bialystok and Lodz, with their modern factories, that put out a better product, and due to demands at the time had begun to surpass the Krynki manufacturers who did not go with the flow of making cheap goods. They began to quarrel amongst themselves and in a short time became aloof and one fine morning they simply went bankrupt.

The work slowly went over to the neighboring towns – Horodok, Mikhalove and Vashilkove, etc. The factories were idle. The spinners, weavers and merchants left Krynki and the town became as idle as a cemetery. The windows and doors of the factories were broken, boarded over. The idleness and quiet cast fear into the population and passing by after the kheder [religious school], boys would avoid this area, as they believed that there were devils there. Jokers would blame the silent steam factories and composed a song about the troubles.

“Yidl approaches and says:

The steam factory goes like a fiddle

Eli approaches and says:

The steam factory goes like an orchestra

Gedalya approaches and says:

The steam factory is out of order,

Fayvel approaches and

Rolls up his eyes.”

Krynki's economic situation became very difficult. Looking at the community institutions in the shtetl, like the Talmud Torah [free religious grade school for poor boys], the bote-medroshim [synagogues, of study], the hakhnoses-orkhim [Sabbath shelter for poor wanderers], the hospital, etc. were poorly maintained. During the good years the bosses were too busy with their big businesses to notice any of this.

Krinik felt like after a wedding. The tumult was still humming in the head, but the pockets were empty. Everyone felt impoverished. People wandered around the market place like after a fire, not knowing what to do to earn a piece of bread.

Little by little people accepted the situation and carried on as best they could. They bought what the gentiles brought during a market day: a bundle of pig hair, seeds, flax, wax, wool and fought each other over an old, holy peasant shirt. They ran on the roads during a market day to stop a peasant with a little grain; then ran back to the shtetl, while the other whipped the horse in order that the Jew would not run after him. All this just to earn a kopeck profit from the trade. And from this business people had to live and pay tuition, pay for marriages and pay one's way out of military service. They wracked their brains trying to survive from one day to the next until times got better.

The fires touched everybody!

One beautiful morning a fire broke out at the market place at Niome the tanner's and one quarter of the city went up in smoke. There was nothing anybody could do and so they asked for help from the surrounding cities. They received a little from here and there and they began to rebuild. First the Christian houses and later the Jewish ones. A lot of places stood empty and before the wound was healed another fire broke out - a larger one.

[Page 42]

It began on Shivoser betamez [17th of Tamuz June/July, a fast day to remember when Nebachanezar broke through the walls of Jerusalem in 586 and Titus in 70 b.c.e] and people had fasted the whole day. It was a very hot day. Everyone was tired. They were exhausted and went to sleep. Just before daybreak a large fire broke out. Screaming was heard. “Fire, it's burning!” People opened their eyes – there were lights in all the windows. Everyone woke up and grabbed the children. The father grabbed the axe – he ran to see where the fire was. I ran after him. I ran to the fire and saw Chemia Moshek's house was ablaze and nobody extinguished it. A second caught on fire, a third.

The Krynki rabbi, Reb Boruch crawled out a window in his nightclothes and begged the butchers to at least grab a hoe. He could not ask more of them. The fire was everywhere and destroyed the entire shtetl. Whatever things could be saved was carried into the synagogue, because it had not burned the time before and everyone was sure it would not burn this time. But it did not take long for the large synagogue, the “Khayeh Odem” [“Life of Man”, title of a well-known compendium of Jewish religious laws] and the Slonimer shtibl [Hassidic prayer house], to go up in flames. All that was left were ruins. Three quarters of Krinik went up in smoke.

The large fires erased all traces of the cloth factories that Krynki had. From all the tired, empty buildings nothing was left.

But it is said that after a fire people become rich. People in the shtetl began to stir, buying old bricks. They were ready to clear out a couple of blocks. It was lively. Some insurance money had arrived and some respected citizens were traveling the world with a document from the rabbi – to make money.

The large synagogue, whose walls were still standing, had not been forgotten. They were working on the building so that it would be ready for Rosh Hashanah [Jewish New Year]. Yudel Laskes helped a lot with the work.

Little by little the shtetl was rebuilt (with nice bricks in place of the rotten wooden houses) one with modern windows and doors (made with frames set into the openings.)

But the Kalter Synagogue was forgotten and was left standing without a roof. Who knows how long it would have stayed this way if not for Yankel Elke's (Mordchilevitsh) and Shaul Zelman from the courtyard. They did not rest until the synagogue was rebuilt. Yankel Elke's tried to make it as beautiful as possible according to the standards of the time. The vault was decorated with fine carvings of pears with an artistic knob in the middle. The carver was Shalom Pinkhas from Grodno and his name was cut into the carving. A lovely Holy Ark was also built (made by Efrim the cabinetmaker) and an artistic cantor's desk as well as a fine door (worked on by Eli Meyer Fishel's).

As known, the poor and guests of the community always prayed in this synagogue.

The Beginning of the Tannery

In Krynki, as in a lot of other towns, there were small wet tanneries that worked cowhides and also made simple soles (one of them was founded about 1864 and later restored by Jakob Kipel Zalkin). The entire morning during market day, the manufacturers would layout his entire “production” on a small, dilapidated wagon held together with string. He hitched himself to the wagon and dragged it to the market place. His wife and children helped pushed it downhill. He stood near the booth of Motl, Chaia Tille's, laying out the bits of leather, and waited for merchants and peasants who were the principal buyers of leather to make bast shoes. The wife and children stood around all day watching the wagon so that the peasants would not steal because back then a gentile buying a small piece of leather was a big purchase. The small piece was used for different parts of the shoe.

[Page 43]

|

Standing on the bima at the right is the shames [synagogue sexton]; on the left is the gabe [trustee of a public institution] |

[Page 44]

The large Krynki leather industry that began with these small leather pieces later became famous in Russia.

The tanners at that time were Yeshiya Shmuel Moshek's, Mates the Tanner, Moshe Velvl and Abrahaml Gimzshes, Jakob Shmuel the Tanner, Eliahu Abrahaml Holeveshke, Abrahaml Meyer Leyb's and Kopel Safianik. Kopel would make safyan [morocco leather] from sheepskins at Yoshe, Chaia Masha's.

This how they worked year in and year out. They bought horsehides from the “kapitse” [skinners[1]], a cowhide from the butcher and kept a couple of Tatars to help during the week (not on a market day). They sold cow hides to a shoemaker for gentile boots and with this they made a living, not having any idea that anything better existed.

Hillel Katz-Bloom

In Krynki, a small shtetl of three to four hundred wooden houses in the 1890's, the population was poor and oppressed. They made their living from the village and the market place. When a peasant arrived by wagon he would be met by Jews in kapotes [long, black coats worn by Jewish men] and women with kerchiefs wound around their heads and there would be a tumult and yelling: “you, what do you have to sell?”

Down near the river there were several large wooden buildings where during the good years, in the past, when Jews had “podvalen” [cellars to store liquor] and taverns, there were liquor distilleries and breweries and Jews made a living from them. With the introduction of the monopoly in Russia, all the taverns and distilleries closed and Jews were left without the means to earn money. Men with entrepreneurial spirits began making tanneries in the old houses where leather was made to sell. Jews worked at dry leather and the Christians in the villages at wet hides.

A kilometer before arriving in the shtetl one could already smell the odor of the tanneries. Old, wooden, low, half-rotten buildings, the walls were damp and there was no ventilation. There was absolutely no sanitation. The workers had never heard of such thing and were not concerned about any of this. The only government official in the shtetl was the police officer. As long as he received his monthly stipend of fifty rubles from the manufacturers, everything was “kosher.”

There was an exploitation of the workers and the working conditions. The majority were former impoverished small storekeepers and former idlers. In winter the wet workers would have frozen hands, as the owners did not heat the buildings. For the dry workers in the drying rooms the heat was unbearable.

[Page 45]

People worked in shirts and sweat poured from their bodies. They worked in these odious conditions without rubber gloves (the owners did not worry about these things). The wet workers hands were damaged from the lime and became infected from the hides of sick animals, with the terrible “Sharbunke” (“Siberian Plague”, a type of ulcerated “carbuncle”). In just the winter of 1896-1897, fifteen workers died from it.

Nobody dared protest or complain about such conditions or the terrible treatment. Rebels like this would have been beaten black and blue and thrown out of the tannery.

Ab[raham] Miller

Jakob Kopel Zalkin was the first to begin working leather in large volume. He owned the factory that later belonged to Hershl Grossman. Although all the manufacturers tanned horsehides, some produced Warsaw soles. All of them worked according to the same system. The same wet tannery had the ceiling over head, broken windows, rotten vats, the same terrible odors from the skins, lime and extracts mixed together that would infect the air of the shtetl.

Never once on a Friday during the day, did we go without seeing a child or a wife bringing a piece of potato pudding to the tannery for a father or a husband. During the wet tanning he stood at the vat, with a scraping iron in hand, and pulled the hide from the carrion. He hurried to finish the work quickly, to be able to leave sooner for the bathhouse in honor of the Sabbath. He wiped a hand dirty from the leather and took the piece of pudding and “enjoyed the feasts” near the vat.

The first to begin production of leather in large volumes in Krynki, besides Jakob Kopel Zalkin (“safyanik”) [morocco leather man] were: Nachum Anshel with his partner Ayzik Krushenyaner and Chaikel Alend who bought the small tannery from Moshe Gimzshes. There were also Jankel Mates' and Hershel Grossman, Leyb Mates', Jankel Moshele's, Yehusha Zatz, Hershel Yankel Elkes, Sevakh Elkes, Shmuel the American, Asher Shiya's, the Blochs, Moshe Szimshonovitz, Eli Kopel's, Israel Ertzki; Rechel's three sons – Archik, Velvel and Israel Leyb and others.

The leather industry quickly spread throughout Krynki until the government looked around and stopped giving out permits to set up wet tanneries in the middle of the shtetl because of the terrible sanitary conditions. After going to a lot of trouble the manufacturers were allowed to go to the other side of the river, at Yenta's fields. The industrialists bought large tracts of land and built immense factories with better facilities, such as large windows and cement tanks. In the new factories they worked horse skins and employed hundreds of workers, masters and apprentices.

The first workers in the factories doing wet work were as previously mentioned, Tatars and their wives.

Not only the Jews in Krynki made a living from the factories. There were also gentiles who worked there.

When Nachum Anshel decided to take up leather manufacturing, he asked Kopel Zalkin for advice. Kopel told him: “If you have enough money to put into it – then do it.” Nachum Anshel was not afraid and a few dozen years later he was the head of the shtetl, the leader of the Krynki manufacturers. He ruled like a strong government official and his word was law. His strong hand was also often felt on somebody's cheek.

[Page 46]

Germans did the dry work. The word “garber” [tanner] originated with the Germans. A lot of the words used in Krynki in the leather tanneries came from them. And when the Krynki young people went into the leather factories, they were taught not only the trade but also the German terminology.

The workday in the leather factories, during the early years, started at five o'clock in the morning and ended at dark during the summer. During the winter they worked from five o'clock in the morning until eight or nine o'clock at night. At five after five in the morning the doors to the factory entrance were already closed.

The weekly wage of a wet worker was three to six rubles

The dry work was done by the masters who were paid by the piece or by two pieces of distressed leather (a horsehide of finely worked leather with minute projections). It took ten to eleven years of apprenticeship to become a master and it cost forty to fifty kopecks a week to learn the trade. The masters lived better than the manufacturers. They lived in nice dwellings, had servants, were well-dressed, splayed cards, drank beer and schnapps and slept until nine o'clock in the morning.

Like the children of Israel in Egypt, the Krynki workers also moaned and groaned under the yoke of the difficult, dirty work. The skin of the wet workers hands was cracked to the bone, from working the hide with lime. They were not able to change their boots, and on Friday afternoon would polish their work boots with cod liver oil and go to the synagogue. Even the dry workers would wear their greasy work trousers on the Sabbath and holidays.

|

Tanners in Krynki |

The First Rabbis and Preachers of Krynki

by D. Rabin

Translated by Jerrold Landau

During the tenure of Rabbi Avraham Charif as rabbi of Krynki, a renowned rabbinical judge and preacher lived in Krynki, known as “Der Alter Maggid” [The Elder Preacher], Rabbi Avraham Yaakov Lewitan. He had a fine manner of oratory. His style of sermons, his manner, and his struggles were in the fashion of the Maggid of Kelm. However, when Rabbi Baruch Lawski was appointed as the rabbi of Krynki, he did not tolerate any rabbinical judges in the town other than himself, and Rabbi A. Y. Lewitan was pushed aside from his post of rabbinical judge. He then left Krynki and moved to a different community, where he served as rabbi. He would go to preach in various places as “the Maggid of Krynki.” However, he returned to Krynki in his old age. He was a teacher of older lads, and he gave classes in the Kowkoz Beis Midrash .

[Page 48]

|

Rabbi Yaakov Avraham Lewitan, “Der alter Magid” |

Translated by Jerrold Landau

Rabbi Yosef the son of Rabbi Asher HaKohen

Rabbi Yosef the son of Rabbi Asher HaKohen was a native of Krynki. He served as the head of the rabbinical court there during the 1830s. The approbations of the rabbis of his generations for his book Kapot Zahav (novellae, didactics, and sermons, Vilna and Horodna, 5596 / 1836) testify to this, as they describe him as the rabbi of that time. They impart importance to the community of Krynki by noting that he was invited “presently to serve as the desired head of the rabbinical court of the holy community of Krynak.” Rabbi Aryeh Leib Katzenelboign, the head of the rabbinical court of Brest-Litovsk, notes this especially, stating that Rabbi Yosef had earlier served as the head of the rabbinical court of Zabludow. Those who granted approbations for that book, which imparted fame in the rabbinical world to its author, mention Rabbi Yosef as “sharp, expert, and learned” and as “a splendid preacher in communities.”

Rabbi Yosef HaKohen signed as the head of the rabbinical court of Krynki in two books: in the year 5593 / 1833 on Avot DeRabbi Natan (with the addition of two essays on the book of Rabbi Eliahu the son of Avraham of Delticz. That book also includes a long list of subscribers from among the notables of Krynki); as well as on the Vilna edition of the Talmud (Ramm edition).

Rabbi Baruch Lawski

Rabbi Baruch the son of Rabbi Shmuel-Meir Lawski was born in Lomza and was educated in Talmud and rabbinic decisors during his childhood by his father, the Torah scholar and wealthy leader who had studied in the famous Yeshiva of Volozhin for a period of time when it was headed by the two famous Yeshiva heads, the Netziv (Rabbi Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin) and his son-in-law Rabbi Rafael Shapiro. During his early years, Rabbi Baruch also served as assistant to the rabbi of Brisk, Rabbi Yehoshua-Leib Diskin, who served as the head of the rabbinical court of Lomza for many years.

Already from his youth, Rabbi Baruch excelled with his straightforward, deep intellect, and in his ability to delve deeply into the words of the early sages. He filled himself with this knowledge, and became well-known. After Rabbi Baruch married a woman from Lomza, he was summoned to serve in the Krynki rabbinate in the year 5643 [1883]. He was recommended to the communal administrators in the town by his friend from the time he studied in the Volozhin Yeshiva – Rabbi Zalman Sender Kahana Shapira, the head of the rabbinical court of Kobryn at that time.

|

Rabbi Baruch Lawski |

Rabbi Baruch settled in Krynki, and his influence was also great in communal and general affairs in the town. His knowledge of Polish and proficiency in Russian assisted greatly in this activism. He was considered to be a great expert in issues of Torah adjudication and general jurisprudence, and he was in demand by many as an arbitrator, to mediate in

[Page 49]

complicated disputes and general court cases. He was sought for arbitration by large-scale, well-known business owners, such as the Szereszewski family, who were famous tobacco manufacturers in Grodno; as well as estate owners and administrators.

Rabbi Baruch Lawski became well-known among the Torah personalities of the generation, due among other things to his work Minchat Baruch – responsa on the Code of Jewish Law, and the Tur Orach Chaim, as well as the laws of Passover and Torah lessons – published in Warsaw in the year 5656 [1896] (138 pages). The Torah personalities of that time would praise that book greatly for its bounty of extensive expertise, and deep sharpness. Large, Torah oriented communities of Lithuania wished to appoint him as the head of the rabbinical court, including the community of Ponevezh [Panevëþys], which sent him a rabbinical contract. However Rabbi Baruch remained faithful to the community of Krynki, preferring to remain there. He served in the rabbinical position there for 20 years, until his death in the winter of 5663 [1903] at the age of 60.

He was buried in the cemetery in Krynki. Masses of people came to his funeral, even from the nearby towns. He was eulogized by eight rabbis from the nearby settlements.

Rabbi Baruch's second book, Nachalat Baruch, was published in Warsaw in the year 5664 [1904]. This 48-page book consisted of 22 responsa and halachic novellae on the Yoreh Deah section of the Code of Jewish Law. It was a continuation of Minchat Baruch. In more recent times, a group of Yeshiva students in Bnei Brak published a second edition of Mekor Baruch, which eventually sold out. Its unavailability was felt by the students. That edition was entitled Imrei Baruch. Additional manuscripts of Rabbi Baruch Lawski on Torah topics and responsa that he left in his estate were not preserved.

We are in possession of details about the Krynki rabbis from 1883. Because of the lack of necessary community chronicles (such as the community record book, and the Burial Society records) we have only the names and details of the rabbis, as far as possible, as was found in the sources that were available to us.

As previously designated the first time a rabbi in Krinik is mentioned is in “Pinkas Mdins Lita” [Book of Records of the Country Lithuania], in institutions for the year 1679 where he is entitled “the Communal Leader, the rabbi Leyb of Krinik”.

Later we have scant details about Krynki rabbi, first from the beginning of the 29th century, for instance:

Reb Osher son of Reb Avigdor ha Cohen was the rabbi in Krynki until 1810.

Reb Arye Leyb, the author of Shaagas Arieh [literally “the Lion's Roar”—a well-known work on Jewish Law] was at first the rabbi in Zabludova (after his father the rabbi Reb Boruch Bendet). He was the rabbi in Krynki until 1814 when he was invited to be the rabbi in Bialystok where he died in 1820. He was known as a sagacious scholar and versed in Talmud, Rashi's commentary, Tosfos and Codes. He was a master of style in Hebrew and was knowledgeable in religious poetry.

Reb Yosef son of Osher haCohen, author of “Kapos Zahav” [literally “The Golden Spoons, a book on Jewish Law and philosophy], the son of the previously mentioned Krynki rabbi, Reb Osher son of Avigdor – became the rabbi in Krynki in the 1830's until about 1838 when he was invited to become the rabbi in Kamenets-Litovsk.

After him, Reb Abraham haCohen became the rabbi in Krynki. He died in 1848. This is all that is known about him.

Reb Yosef of Krinik, Reb Yosele Lipnishker, was first the rabbi in Lipnishok and afterwards in Krynki where he died in 1867. He was a student of Reb Chaim Volozhyner in his yeshiva and in a letter in 1865, he described the situation of the study of Torah in Lithuania and Poland, before the above mentioned yeshiva was founded and stirred the Jewish community to open the locked yeshiva once again. In the shtetl Reb Yosele was considered a pious man and on his grave in Krynki there stands a monument where believers would come to lay request notes for him to defend them.

[Page 50]

Reb Abraham the sagacious scholar, “Reb Abrahamtchik”, “der alter rav” [the old rabbi] from Krynki died there in 1872. He was known as a man satisfied with little.

It is likely that was after him until 1883 rabbi in Krynki, Reb Gad Moshe son of Zelman, a brother-in-law of the Novy Dvor rabbi Reb Abraham Tsvi Hirsh. At the same time the Rabbinical Judge in Krynki was RebShlama Chaim Mishelev, previously the rabbi in Novy Dvor who is buried in the Krynki cemetery.

Reb Boruch son of Shmuel Meyer Lavski who came from Lomza, studied in the Volozhyn yeshiva, and when he was young was described as a bright, upright man with an aptitude to penetrate deep into the ancient rabbinical authorities. He became the rabbi in Krynki in 1883 having been recommended by Reb Zelman Sender Shapiro, who was the rabbi in Kobrin and who was acquainted with Reb Boruch from their days on the yeshiva bench in Volozhyn.

Reb Boruch soon occupied an important place in community affairs and being well versed in Polish and Russian helped. He was a specialist in lawsuits brought to the religious court and in jurisprudence. People bringing lawsuits would turn to him, not only Krynki manufacturers and merchants, but also people from near and far in the area, for example the Grodno Tobacco manufacturer Shereshivski and noblemen, for him to decide or comment on their disputes.

Reb Boruch had also acquired a name among the Torah scholars with his work “Minchas Boruch” [literally “the Offering of Boruch”] – questions and responses on the “Shulhan Aruk”, [“Prepared Table”, title of a book containing all Jewish religious laws]. Because he was a great, well-versed, sagacious scholar of Torah, a lot of communities, like Ponovezh for example, offered him the rabbi's chair, but Reb Boruch was faithful to his Krynki community where he remained as rabbi for twenty years until his death in 1903.

While Reb Abrahamtchik was the rabbi in Krynki, Reb Abraham Jakob Leviton was the judge and preacher – he was called “der Alter Magid” [the Old Preacher]. He was a good speaker and a follower of the Kelm magid's path and manner and his fight against petticoats.

But when Reb Abrahamtchik died, Reb Boruch Lavski took over as rabbi and he did not need somebody to help out as judge. So Reb Abraham Jakob was removed as judge and “der alter magid” left the shtetl and took up the rabbinate in another community and traveled around as the “Krynker Magid”.preacher.

In his old age he returned to Krynki, was a teacher in the religious public school for older boys and spoke before the people in the “Kavkaz” synagogue.

Some time later Reb Tsvi-Hirsh Orlanski, “Hershele Dubrover” became the magid in Krynki. He was famous for preaching in favor of Zionist societies and the settlements in Israel. Among the common Jews he had managed to influence were the fervent Hasidim, but as told by Ab. Miller, Rabbi Reb Boruch and the bosses “were not convinced by him” and in 1887 he left for Szczuczyn (Lomza Province).

by Dov Rabin

Translated by Jerrold Landau

|

Jakob Zalesk |

“Enlightenment” Winds

Signs of the winds of “enlightenment” began to blow also in Krynki about the last quarter of the 19th century. This is evidenced in the correspondence from there in the “HazFira” [newspaper] dated the 7th of Nisan [March] 1877, written by the enlightened man Jakob Leyb Zaleski in which he complains about the sad condition of Jewish education in the shtetl. He writes “education is being neglected and is run by the teachers who tire out the children with gemore [part of the Talmud commenting on the Mishnah], before they know how to read Tanakh [the Pentateuch or Five Books of Moses] as it should be. The Talmud Torah [free religious grade school for poor boys] students are ruined and hundreds of children from poor families wander around in the streets and nobody is concerned about them. They are not even able to write a couple of lines in correct Hebrew or sign in Russian.

“The previous summer there a teacher, an enlightened man from Grodno, M. Volgel, who had, on his own, and with a permission from the government, opened a school here in order to teach our children Hebrew and Russian. We hoped that his would be a modest beginning that would grow larger. Unfortunately, several people who felt that the school was a crooked business, began a smear campaign that the children would be led away from a Jewish life. The situation for the school has become very difficult and as a result it will not be able to hold out for long.”

Later Zaleski opened a school in the shtetl. As mentioned in the Jewish Russian weekly periodicals “Russki Yevrei” [Russian Jews] and “Voskhod”, since August 1881 he had gone regularly to endeavor to get a subsidy from the “Society for Trade and Agriculture among Jews in Russia.” The subsidy was for a class to train young women as skilled workers in his school. He received the first subsidy in 1887 when the Krynki community agreed to pay an equal subsidy for this purpose. In 1901, 30 young women were enrolled at the school.

Zaleski also tried in 1881 to buy agricultural land, through the same society, for six Krynki Jewish families in the area, near Krusheniany. But in the mean time the Russian government had forbidden Jews to buy land outside the city limits.

About Jakob Leyb Zaleski, his son, Moshe Zaleski, today he is a manager of the Office for Hebrew Community Education in Cincinnati (United States) and Professor of Hebrew at the university. There he wrote that his father was a true Jewish enlightened man, devoted to the pursuit of “esthetics of beauty in G-d's tents.” As for the broader picture and his proficiency in several languages he was self-taught. He was a reader of Hebrew and world literature and created a rich library, but mainly he was a trustee for various associations.

Footnotes

by D. Rabin

Translated by Jerrold Landau

The Size of the Jewish Population

In the census that took place at the threshold of the 20th century in 1897, 3,452 Jews were enumerated in Krynki, forming 71.45% of the general population – in contrast with the 3,336, or 84.62% (according to the “Geographic Lexicon of the Kingdom of Poland” 1883) in the year 1878, and in contrast with the 1,856 in the year 1847. It can be seen that the Jewish population almost doubled during the course of 40 years. From that point, however, it barely continued to grow during the 20th century, and the percentage with respect to the general population even declined slightly. This was despite the natural growth of the Jews, and the gains to the Jewish community from those who moved to Krynki and became permanent residents, especially during the flourishing years of the tanneries. The reason for the relative stagnation of the Jewish population in the city was – emigration.

Individual, daring Jewish youths from Krynki already immigrated to America during the final two decades of the 19th century. However, the waves of hundreds of emigres began to stream out of there from the time that the Czarist government began persecuting the tannery workers who were awakening toward a struggle for humane working and living conditions, and young Jewish revolutionaries were aspiring for freedom and equality. At that time, especially from the year 1902, many of them were forced to leave their homes en masse and escape from Russia due to the persecution. They especially went to the free United States. With time, this emigration increased, especially after the revolt in Krynki in the year 1905, and during the years of the depression that affected the tanning sector following that. When the first immigrants began to become acclimatized to their new land of refuge, they began to send ship tickets to their families and relatives, so they could join them. With time, the number of communities of Krynki natives in the diaspora increased to the point where that number came close to the number in the hometown itself.

The Situation and Struggle of Jewish Krynki

The Jews of Krynki had the same lot as the more than 6,000,000 Jews of Russia during the period under discussion, especially in the communal and political arenas. They suffered from the same decrees, oppression, and restrictions that the inimical regime decreed upon the general Jewish population of the empire, including Krynki. During that period, they continued to find means of restricting internal Jewish life – especially in the arenas of religion, culture, and general life – in which the [previous] oppressive, inimical, Czarist regime had not dared involve themselves with previously. Apparently, the writers of articles in Jewish newspapers, and even the researchers, did not report much about this regarding Krynki in particular.

A general Jewish event that especially shook up and frightened the entire nation in Russia was the slaughter in Kishinev in 1903. It found expression in the Jewish newspapers, even regarding Krynki (Hatzefira, Warsaw, from June of that year). These articles included the names of heads of families in the town who gave donations toward the assistance of the victims of the pogrom. The list included the amounts donated. These lists included tens of people who volunteered to collect the donations, and testify that all strata of the community participated – the manufacturing tycoons, as well as their employees, the tanners, and those of other sectors (see details on page 226).

The most important political event, as well as the most “sensational” that took place in Krynki, , the heroes of which were the Jewish tannery workers and the revolutionary youth – was the revolt against the Czarist regime in January 1905, when the local “sisters and brothers” (Yiddish nickname for the youth who fought for freedom and equality) expelled the leaders from the town and took the government into their hands for several days. We will relate more about this.

Jewish revolutionaries from Krynki, members of the general political streams (such as S.R. – Socialist Revolutionaries of Anarchists) also resorted to personal terrorist methods in their battle – became known even outside their native town for their deeds of bravery that they displayed with their self-sacrifice.

The local Jewish tannery worker, Sikorski, a member of the S.R. took part in the clashes that his faction organized against the murderous interior minister of Russia, Plehve[1], who was also responsible

[Page 54]

for the pogrom in Kishinev. Sikorski joined his two friends Sazanov and Kalyayev in ambushing the inimical minister next to the Warsaw paths in the capital Peterburg, with dynamite bombs in their hands. The first one, thrown by Kalyayev, killed Plehve.

The 17-year-old Anarchist Niumke (Binyamin) Frydman, ended his young, adventurous life in a clash that he himself planned, based on his own conscience, against the cruel director of the Grodno prison, taking revenge on him for that which he perpetrated upon young Jewish girls. The girls were active in the tobacco factory in Grodno, where they went on strike, and were put in prison by the police when Niumke was imprisoned there. The head of that prison ordered that they be beaten, and their screams that reached the heavens frightened the heart of the young revolutionary. When he was freed, he ambushed the perpetrator, and shot him to death.

It is appropriate to note here that Yossi Galili, a commander of the Haganah in Israel and minister in the government of Israel, related in the name of the late Eliahu Golomb, one of the founders of the Haganah in Israel and its renowned leader (in the book Eliahu Golomb – Chevion-Oz volume II, Tel Aviv 5615). Minister Galili writes that at one point, Golomb incidentally discussed his youth in Krynki (he himself was a native of Wolkowysk, a city close by). Regarding this, he recalled the brave deed of the aforementioned Niumke, who died taking revenge for the disgrace of the striking Jewish girls.

No less important from a general perspective, especially in the annals of the Jewish workers' movement, were the daring, fierce strikes arranged by the Jewish tannery workers in Krynki in order to attain humane conditions in their work and lives. This is a long story, and we will later present it in full detail.

Tanneries – the Foundation of Life in Krynki

The tanning industry was established already in the middle of the 19th century as the vital cord of general life in Krynki. Even then, a portion of the Jews of the town continued to earn their livelihoods, or part thereof, from the weekly market day in the town, to which the villagers from the surrounding area would come to sell their produce and purchase their necessities from the peddlers or the products of the Jewish tradespeople. They would also taste “tasty food” and satiate themselves in one of the Jewish restaurants. However, the pulse of economic life in the town had now become the local hide factory, which not only employed and sustained its workers and owners, but in an indirect manner the entire network of local commerce, trades, and services.

By 1896, 20 tanneries were already operating in Krynki, tanning horse hides. These employed hundreds of workers, including a percentage of Christians. The revenue of the enterprises was large, and their owners became increasingly wealthy. Since there was no shortage of Jewish initiative in Krynki, the number of tanneries continued to increase, along with their employees. They grew in size, and their strength increased. Raw material started to be imported from afar, from Siberia and the Caucasus, and even from outside the country – from Germany, Austria, France, and even North and South America. The products were now marketed in southern Russia and other areas of Russia's vast expanse, as well as abroad. In 1897, the number of tannery employees reached between 500 and 700. In 1898, it reached 800, and in 1921 – 1,000. Later, it even reached 1,100 (of which 160 were gentiles), in 67 factories.

At the time of the Russo-Japan War in 1904, the value of the leather products increased significantly. The soldiers of the Czar, as well as others, required boots. The demand for leather increased, and the pride in the tanneries increased. This continued for several more years.

The Situation with the Tannery Workers

However, even when the hide tanning in Krynki was already taking place in full force, and the manufacturers, like their comrades in this branch in the northwest district of Russia, had attained the status of powerful tycoons, reaching the status of wealthy business owners within their people through their professionalism – the situation of the tannery workers was the worst of the worst. Their salary was negligible and their workday extended from 5:00 a.m. to sunset on the long summer days, and until 8:00 p.m. during the winter, and to an even later time on Thursdays and the eves of festivals. From time to time, they would even work on Saturday nights.

The salary of the “dry” workers was not set at all. The manufacturers would give over this work to “professionals [or experts] on a contract basis in order to ease their efforts and to earn more profit. These people would hire assistants and young apprentices for this purpose, and take advantage of them without bound. The wages were set by “time”

[Page 55]

and the accounting was calculated at the end of six-month terms. The professional would grant an “advance” solely according to his goodwill.

The worker would require special mercy in order to be able to pay several rubles for a physician, in the event of a birth in their house, for a joyous celebration, or in the event of a tragedy, Heaven forbid. Throughout the entire “term,” the worker was forced to purchase or order his provisions on credit, at a price and with the conditions that were appropriate to the issuer of credit. Furthermore, it happened more than once that the professional would announce a “moratorium”[2] or bankruptcy at the end of the term, or would simply disappear from town with the wages of the unfortunate workers stolen in his hands.

There was a set rate for a penalty for a worker for losing or breaking a tool, or for spilling a bit of tar. For complaining about such a travesty, and certainly for any refusal, the worker was liable to pay by being fired on the spot, possibly along with an appropriate beating. Furthermore, the “embarrassed” professional would inform the credit issuers to cut off the worker, for the fired worker could no longer be depended upon to pay his debts. Furthermore, in order to obtain work in a different enterprise, the worker would have to present a letter of recommendation from his former employer…

From the perspective of protecting the health and security of the worker, frightful conditions prevailed: crowding, filth, stench, a lack of air, and the absence of any ventilation. In the “wet” departments there was mildew and moisture. In the winter, there was a harsh cold, to the point where the fingers of the workers would freeze and even stick to the metallic areas of the tubs used for washing and soaking the hides. Burning heat pervaded in the dry rooms, with the constant sweat draining the body and energy of the worker.

Tuberculosis and rheumatism were therefore common illnesses amongst the tannery workers. The “wet” workers would often suffer from attacks of malignant abscesses – a condition caused by the hands touching the hides of affected animals. The skin on the fingers of the workers was usually fissured from constant immersion in the limewater used to soak the hides. The use of rubber gloves in this type of work was still unknown. The few directives regarding the Czarist factory laws indeed required such protection for the life of the worker, but the employers ignored them. The government inspector in charge of these laws was satisfied to receive hush money from the manufacturer, with the addition of a portion of liquor, as was customary.

The health and even the life of the worker, as well as his energy – was even more wanton in those days. No workers organization existed, and the Jewish day laborers were lacking any certificate confirming their most basic rights, let alone their social rights. The workers were dependent on the mercies of the employer, and they relied on his “propriety” in all workplaces.

It should also be no surprise that no small number of gentile workers were employed in the “wet” labor. These were “half” farmers, uneducated, whose tanning work was not their only source of livelihood; whereas the Jewish workers who came to the factory to work had the intention of training themselves in the work, and rising to the level of a professional who could supervise workers, and amass a sum of money so that they could open a small tannery or some other business of their own. Therefore, every worker attempted to attract the attention of the employer, so that he could get ahead and advance as quickly as possible. The Workers Union was still an unknown concept.

Tanning work was justly considered within the Jewish community, in accordance with the conditions of those times – as backbreaking, dirty, low-level work. The odor of carcasses and lime would “go before” the tanner and accompany him constantly, even on a day of rest – for he was unable to purchase a change of clothes or boots. The external form and the odors of the workers was unpleasant to the hide manufacturer when they came to worship together with him on Sabbaths and festivals in the common synagogue for all tanners – until the workers saw fit to separate and to set up a separate Beis Midrash for themselves. Furthermore, the tannery workers even made a Sabbath for themselves in the cultural-religious arena, and in 1894, they founded (according to Hatzefira, number 264 of that year) a union called Poalei Tzedek, whose “members were workers in factories, 400 in number.” The purpose of the organization was “to hear lessons from a preacher in the house of worship that they set up for themselves for daily worship.” Indeed, from that time on, their Beis Midrash served as a gathering place for meetings regarding secular matters, to consolidate the struggle that was to come to improve their conditions of work and level of life, and even more so, to raise their level of respect amongst the people.

[Page 56]

The Beginning of the Struggle of the Tannery Workers

The time of the struggle of the tannery workers in Krynki was approaching. Already in 1894, the first strike of the Jewish tanners in Vilna broke out, and the manufacturers were forced to raise the wages of the professional workers. The success of this strike struck far and wide throughout the tanneries of the entire district. Around that time, a local tanner who was a witness to the large-scale weavers strike that broke out in that year in nearby Białystok, arrived in Krynki. Similarly, a carpenter who worked in Grodno and knew about the awakening within the Jewish workers there to the struggle for their rights, also returned to his home. Individuals, youths, and workers, especially from Białystok, who had been taken by the “new” revolutionary political winds, also arrived in Krynki.

The memoirs of Av. Miller states that “In the summer of 1897, new faces began to appear in Krynki. Melamdim [traditional teachers] began to teach a new doctrine to the tannery workers in our town – beginning with the young and later to the older ones. They began by teaching the aleph beit, and those with sharper minds, with the study of Gemara. They began to secretly discuss the meetings that would take place in the evenings behind the Christian cemetery or in the Razbyonikow Forest. – – – Suddenly, the eyes of the workers were opened to see a path to improve their dreadful situation. The workers' songs, one more endearing than the next, had special influence. The youth joined the revolutionary movement with full enthusiasm. Krynki was frothing like a kettle. Everyone was confiding and whispering one to another. Pairs would go for a stroll, and turn through various alleyways, to a certain point in the forest, where they would listen to speeches and sing workers songs.

Things quickly became “practical” – with deeds. The activists were to gather in a large gathering (Schodka in Russian) in the aforementioned forest, 5-6 kilometers from the town to make a “covenant” of unity amongst the workers and to agree to keep the matter of preparing for action secret from the manufacturers and professionals. When those gathered arranged themselves into a semicircle, a mysterious voice was suddenly heard from a dark, hidden corner describing in an emotional fashion the difficulty, to the point of unbearable life of the tannery workers, and their slavery. The hearts of the audience were pulsating. The voice stopped when the emotions of the crowd reached their pinnacle.

Now, the crowd was asked to stand on their feet and arrange themselves in a circle. One of the participants said that rain began to fall, but the entire camp did not move from their places one iota. The voice was then heard once again, posing poignant questions to the crowd, such as: do they certify the description? Are they prepared to unite and keep everything that had been discussed from the employers? After the response, everyone shouted out in a loud, decisive voice, “We are prepared!” They were called upon to take an oath regarding this. Then, a certain comrade appeared with a pair of tefillin in his hand. He raised them up high (according to another version – also with a Bible), and the crowd repeated aloud the words that were uttered by the mysterious voice – to maintain the unity and to guard the secret about that which was said and heard at the gathering. At the end, the “people of conscience” amongst the crowd joined hands and sang a revolutionary song of oath.

The First Strike

One did not have to wait too long for the pretext to declare a strike. An opportunity arose when a professional in the tannery of Hershel Grosman slapped a worker on the cheek. This deed aroused the fury of the workers in all factories, and at a general meeting of the “dry” workers, it was decided to not come to work the next day.

At first, the manufacturers and professionals thought that this was only a prank by the workers, and that they would hasten back to their work when they had any suspicion that they would eventually starve. However, the employees quickly realized that this was not the case. One of them, Izik Krusznianer, even stated before his friends in public that “he was willing to swear that this was something that was organized and planed from the outset.” Now, the manufacturers indeed got scared, and they sent messengers to the workers to find out what was going on. Then they found out that the strikers in the “dry” work were demanding that the secondary contracting with the professionals be cancelled, and that they be paid weekly directly by the manufacturer, as well as a 12-hour workday.

The employers had not imagined such brazenness. Now they searched for a way to influence 350 workers to return to their work – whether through pressure from family members, or through the involvement of the rabbi of the city. The rabbi, Rabbi Baruch Lawski summoned one of the “rebels” – Herschel Wajnberg (Pinks), whom he knew to be an intelligent person, who was also familiar with

[Page 57]

halachic jurisprudence. He agreed and went to the rabbi, but was greeted with words of reproof regarding the strike of the workers, which the rabbi interpreted as taking the law into their own hands, without first approaching the rabbi first as Jews do, and without going for a rabbinical adjudication [din Torah]. Wajnberg responded to the rabbi in his manner, also with words of halacha, and he proved to Rabbi Baruch that he was supporting the side of injustice, the side of the employers.

When the manufacturers realized that the workers were standing strongly for their demands, they decided, with the agreement of the rabbi, to turn to the district governor in Grodno. A group of gendarmes were sent to Krynki. This was the first time that such a number came to that town. They immediately started to oppress the leaders of the strike by capturing them and beating them with murderous blows. The manufacturers also asked the police to lock the doors of the Beis Midrash of the tannery workers, so as to prevent the strikers from gathering there for deliberations. However, they too did not hide their hand on the plate[3]. On the Sabbath morning, they took over the large Beis Midrash, where the manufacturers worshipped. They also took over the seats on the eastern [wall] [4]. They set up guards to prevent the entry of the employers, and distributed the choicest Torah honors to themselves. After the services, they locked the doors of the Beis Midrash and took the keys with them. The manufacturers were forced to approach the police and request that they open their house of worship

However, the persecution increased the bitterness of the workers, and the battle grew sharper. In the meantime, tens of the strike leaders were arrested and sent to prison in Grodno, Hershel Wajnberg among them.

At the end, the manufacturers realized that they could not defeat the strikers, and they agreed that from that time, the workers would be paid a weekly salary, and that they would work from 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. – that is, only 12 hours a day. The “historic” strike in Krynki ended with a victory for the workers.

Av. Miller writes, “Thus began the period of strikes in Krynki. The workers realized that they had power. The arrogance of the professionals began to abate, and the workers no longer received slaps on the cheek from their employers. Workers in other sectors, including shoemakers, tailors, carpenters, and the like – learned from the tannery workers, and began to come with demands. They too were successful.

The Continuation of the Struggle of the Tannery Workers

The manufacturers were not happy with their downfall, and during the next work “term” after Sukkot of 5658 [1897], they convened a meeting with the rabbi, and decided to set contracts with the professionals for three years, and to only accept workers who were not among the “rebels” and who agreed to work for 14 hours a day. The workers, and this time also the professionals as well, did not agree to this, and began a strike. The employers requested that the district governor send the army to Krynki to impose order. They also gave over the names of the “rebels” to the authorities. There were arrests based on this, and the villagers were summoned to disrupt the strike. They were incited to beat the strikers. A father, who defended his striking son who had been attacked, paid with his life.

Army brigades that arrived in Krynki perpetrated attacks on the workers on the streets, and beat them. The soldiers even took over the house of worship of the tannery workers. They removed the Torah scrolls from the room and turned it into barracks. The workers then went to the Beis Midrash of the wealthy people and delayed the reading of the Torah[5]. The police were summoned, and they dispersed the workers. Their commander took out the Torah scrolls from the holy ark, making sure to cross himself first, in order to enable the Torah reading to take place.

The strike dragged on. The workers, hungry for bread, did not have the strength to stand up before the army and the strikebreakers who had been brought in from Białystok and other cities, even from far-off Berdichev. Finally, they were forced to give in and to return to a 14-hour workday.

In June 1900, another strike broke out, this time with the “dry” workers, who demanded a 12-hour workday. After the intervention of the government representative who arrived from Grodno, the manufacturers succeeded in convincing 50 workers (from among the 300 strikers) to return to their work. However, such a workforce alone did not make it possible to operate the tannery. Since the employers did not succeed this time to bring in strikebreakers from other cities – for the tanners there knew about the strike – strikebreakers were brought in from the surrounding villages, and the police were asked to treat the strikers with a heavy hand. They even conducted searches in their houses, and arrested them.

The strike dragged on. Under [financial] pressure, the workers went to the estates in the area and hired themselves out for seasonal agricultural work for a small wage, which they divided up among their striking comrades. Now

[Page 58]

the manufacturers approached the police chief to convince the estate owners to no longer employ “the rebels.” After a strike of seven weeks, the hungry workers were again forced to work 14-hour days.

However, in the following strikes, in the years 1903 and 1904, the tannery workers succeeded in improving their work conditions, and in 1905, the workday reached eight hours. With time, they also found effective ways to punish the employers for improper behavior toward the employee.

In the merit of their constant, tireless, strong struggle, the tannery workers not only succeeded in attaining humane conditions and much better physical circumstances in their work – but they also raised the status of their trade amongst the public. It was no longer considered “lower class” but was even regarded as honorable. Furthermore, through their struggle, the tannery workers themselves earned an honorable place in the front ranks of the Jewish workers movement in Russia.

The Political Activities of the Workers and Revolutionaries of Krynki

The root causes of the revolutionary movement among the workers of Krynki, with all the fame it attained, was similar to that of the Jews of Russia in general. There were three: human oppression and overlording at the hands of the harsh, barbaric (to our dismay, we must state: in accordance with the concepts of those days) Czarist regime; the harsh taking advantage of the workers, and the extreme oppression; and the persecution of the Jews and the rendering of their life valueless. Incidentally, most of the Jewish revolutionaries at that time thought and believed that the change of regime of the state would also bring redemption to their people in that land.

According to specific information, groups of Jewish revolutionaries already sprouted in Krynki during the 1890s. Some of their members even conducted publicity in Grodno, and attempted to organize the tailors, carpenters, shoemakers, and especially the employees of the Szerszewski tobacco factory there. We can surmise that these groups drew their revolutionary ideology from the manufacturing sector of Białystok. The Jews of Krynki maintained strong connections with that city, and continued to be influenced by it for many years thereafter, especially in the spiritual arena. These revolutionary groups were the ones who initiated, organized, and directed the strikes of the tannery workers in the town, about which we have already discussed extensively. Strong, daring youths who were only between the ages of 18-22 were the ones who were active in such groups. Many of them were imprisoned by the government, and were even put to trial in the years 1898-1899, some due to active participation in organizing strikes, and others for belonging to “workers groups.” Some were sentenced to various harsh punishments.

Seventy tannery workers participated in the celebrations of May 1, 1901, in the forest near Krynki. They enjoyed themselves there until late at night. They listened to speeches and sang revolutionary songs. That year, the tannery workers raised a ruckus at the wedding celebration of one of their co-workers who had refused to take part in their strikes. Three of the perpetrators of the “disturbances” (in the language of the police) were arrested and put on trial.

At the beginning of 1902, a demonstration took place in Krynki during the funeral of a worker, where they sang revolutionary songs. That year, the immigration to America of the workers increased, and Krynki revolutionaries were persecuted by the police.

At the international Socialist congress of 1904 in Amsterdam, the Bund committee (the general union of Jewish workers of Russia, Poland, and Lithuania – the democratic Socialist movement) of Białystok was represented by 2,240 members, of whom 250 were from Krynki. This was a relatively large contingent in comparison with the clandestine movement in the town in those days, especially since other Jewish youths in Krynki were affiliated with other revolutionary movements, including the S.R. (Revolutionary Socialists), and especially with the local active organization of anarchists. In those days the Bund was the leading faction amongst the Jewish workers and revolutionaries in Krynki, as in the Jewish Pale of Settlement in general.

Anarchist Activities

The influence for the anarchist groups in Krynki came from Białystok, especially from the group headed by “Yankel Professor” – that is Yaakov Kropliak, a native of Zabłudów, close to that city. He later became a Yiddish writer, author of books, editor, and translator. Betzalel Pocbocki, a Krynki native, one of the first of Poalei Zion in the town, writes in his Yiddish article on that topic that there were followers from all streams and sub-streams among those groups. There were many spokespeople and counselors in this movement, different one from another, for the personal individual fundamentals were decisive. Most were among those who felt that acts of terror were a necessity, to be directed against the Czarist authorities

[Page 59]

and those who oppressed and took advantage of the workers. They also justified conducting confiscations and expropriations (Achsim in their language) – for they claimed that since the workers were prevented from receiving the full value of their toil from their employers, they should restitute what was stolen through different means.

Indeed, various “operations” were carried out, called “actions” in the lingo of the perpetrators – not only confiscations. Thus, the manufacturer Shmuel Weiner, the “American” so to speak, was shot and killed on the last day of Passover by 17-19-year-olds, as he was coming home from synagogue services. Sometimes the anarchists would plant bombs, and not just for a specific reason. One was at a meeting of manufacturers, and it did not injure anyone. Anarchist demonstrations took place in the town several times, at which the revolutionaries dressed completely in black and sang anarchist songs. If the townsfolk would even “smell” the approach of such a “celebration” they would lock the shops (B. Pocbocki continues to relate), and passers-by would hide in the houses. The town strongmen would stand in organized fashion and wait for the Cossacks to come, to influence them to treat the stormy youths mildly.

There were cases when the anarchists were arrested, brought to trial, and accused for what they had done. Not only would they refrain from defending themselves, but they would also bring false defense witnesses, and would accept the guilt of their fellow upon themselves. This was all in order to take over the court lectern so that they could make declarations against the oppressive police and state oppression. They would do everything, including taking up arms, to free themselves from those who would carry out the verdicts against them. They would clash with the police even after they left Krynki, being unafraid of a death sentence, or deportation to Siberia for backbreaking work that would be decreed upon them. More than one paid with their lives when carrying out dangerous missions taken upon themselves.

Krynki anarchists were also active in various activities outside their town. One of them, Aharon Velvel (Yankel Bunim's) was the head of the attack brigade (Hakravit—Boyuvka) of Białystok. Among other things, he was the head of a group that attacks a police guard that was taking political prisoners, and freed them. Krynki youths would also be called upon to arrange “revolutions” in other towns. One of them was Yankel Caini, one of the most talented battlers. The Krynki anarchists attacked the post office in the town of Sidra in the Sokolka district. One of them was killed in this action. In 1905, a group of anarchists, including several Krynki youths, prepared to clash with the rule of the city of Odessa.

One of the strongest of the Krynki anarchists youths, very bold and who was involved with the most difficult actions – was Niumke (Binyamin) Frydman. Niumke merited being mentioned by the late Eliahu Golomb, the head of the Haganah in the Land of Israel in his time and a leader of its settlement and the Workers Unions (in the book Eliahu Golomb – Chevion-Oz, vol II, Tel Aviv 5715 [1955]) – for one of his actions in which he gave up his life. We will discuss this later.

Niumke, the son of a very poor family, had a father who suffered from a skin disease, based on which he was given a dishonorable nickname – joined a stormy group of anarchist followers (a group with no leadership or power of coercion) already at the age of 15. He already stood trial at the age of 16 for throwing a scare-bomb from the balcony of the women's section of the Beis Midrash, which exploded without injuring anyone. Those upon whom the bomb was thrown hired one of the best lawyers to defend the accused, and testified in court that not only did Niumke not throw the bomb, but also – they swore – that he was pious and worshiped daily in the Beis Midrash. It seems that the adjured judges found him not guilty, but Niumke found his own way. He declared that it was specifically he who threw the bomb, and that the witnesses testified in his favor out of fear of revenge from his brothers. He concluded aloud, “Long live the Socialist revolution!”

Due to his young age, they did not sentence him to death, but rather to deportation to Siberia for harsh labor. However, at one of the stops on the journey, Niumke participated in a prisoners revolt against the guard that accompanied him, and was thereby freed. His comrades provided him money to escape abroad, but he refused, claiming that he had yet another action to carry out.

He traveled to Grodno to take revenge against the director of the prison in which had had previously been imprisoned, and under whose watch some imprisoned Jewish girls were beaten. The girls were imprisoned for participating in the strike in Szerszewski's tobacco factory. Their screams and cries

[Page 60]

during the beatings moved Niumke, and he decided then to take revenge upon the cruel person at the first opportunity. Niumke's brother describes in his Yiddish article here that he ambushed the evil man next to the gate of the prison and shot and killed him with his revolver. When the police chased after him, he escaped into one of the houses, from where he succeeded in shooting to death one of the pursuers who tried to capture him. He continued to shoot at the rest of the police, and when he had only one bullet left, he put an end to his own life.

This deed of Niumke, “who arose to take revenge for his people and shot the head of the institution that tormented Jewish young women” – was brought to the fore, as has been noted, by Eliahu Golomb. On one occasion, when he was dealing with the attacks of the Turks upon the Hebrew settlement in the Land of Israel during the First World War, he relates, according to Yisrael Galili, that when in those days Golomb was commanded, along with other Jewish workers, to work for the government on the Sabbath, “A burning fire overtook him, and he recalled the memories of tribulations and resistance from his childhood days in the city of Krynki in the year 1906, when his friend Frydman risked his life to the point of death for the honor of his sisters of his nation.”

As has been noted, the Jewish tanner Sikosrski is numbered among the young revolutionaries of Krynki, who became known also far from their native town for their daring deeds, at which they they risked their lives. He was one of the members of the S.R. party, and he participated in the attack of the murderous Russian Interior Minister Plehve, who was responsible for the Kishinev pogrom. In accordance with orders from the party, he and his comrades Igor Sazanov and Sergey Kalyayev ambushed Plehve on July 5, 1904, next to the Warsaw crossroads in the capital Peterburg, with dynamite bombs in their hands. Kalyayev threw his bomb first toward the bloody man and killed him. Sikorski was later exiled to Siberia, from where he never returned.

Rebellion in Krynki

The general political event, as well as the most sensational in Krynki, the heroes of which were the Jewish tannery workers and revolutionary youth – took place in January 1905.

Already a month before this, the federative committee of the Bund and of the Polish Social Democratic party of Krynki decided to “confiscate” the mail in nearby Amdur. On December 6 (19)[6] 1905, the matter came before the Attack Brigades (Boyuvka) of the aforementioned committee. 1,368 rubles of cash were “confiscated” as well as stamps, postcards, a sword and a loaded gun – everything was “donation” to the battle against the oppressive regime.

However, the spirits in the town were stormy and shaken up after news of the bloody Sunday in Peterburg on 9 (22) January 1905, when a mass of workers, headed by the priest Gafun, while they were on their way to the palace of the Czar to deliver a letter of request for an improvement of their status – were attacked by bullets by the police, and many of them were killed. The storm increased further when they found out about the strike of railway workers that broke out in the town.

Without waiting, the aforementioned federative committee called upon the workers of the town to strike, to conduct demonstrations of solidarity with the railway workers, and to attack all the local government institutions. All the workers in Krynki, of various trades and factions, more than 1,500 individuals including gentiles, responded and gathered in the synagogue for a meeting. From there they went out to a demonstration, on a day of heavy snowfall. The city center was fully on strike, including all the shops. Bearers of red flags (according to the version of B. Pocbocki – also the black ones of the anarchists) were marching at the head. Calls against the police and in favor of revolution were heard from the crowd, accompanied by noisy pistol shots [bullet-less] and the singing of La Marseillaise, with the Attack Brigade [Plugat Hamachatz] advancing along with the group.

The police and government people disappeared completely. As the demonstrators advanced, they overturned telegraph poles and ripped the wires, entered the post office and damaged the telegraph machine and accessories and took them out of use – in order to cut off communications with the outside. They also destroyed the office apparatus and burned the stamps. They removed the picture of the Czar and shot it with bullets (as is stated in the report of the district governor of Grodno to his superior in Vilna). Then, they turned to police station and the Jewish registration office, where they destroyed everything that they found, especially the pictures of the kings of Russia and the “suspicious” citizens in the eyes of the authorities. The heads of the revolt removed hundreds of blank citizenship papers and passports, as well as the seal. This “loot” was later of great benefit for the revolutionary movement to provide “official” certificates for escaped political prisoners, and to enable them to reach a safe spot.

From there, they turned to the office of the director of the village subdistrict and destroyed it, as well as to the government liquor distribution office,

[Page 61]

where they took by force of arms the large supply of bottles of drinks. They completely destroyed the remnants of the government apparatus that still remained in the town, due to illness or other reasons. They removed their weapons. Now, the active militia prepared for actions to ensure local order.

The demonstration also took place in the nearby Tatar village of Kruszyniany, where tannery workers of Krynki lived. There too, they destroyed the government liquor distribution depot. From there, they moved in a mass demonstration to the nearby village of Holynka and to the town of Greater Brestowica [Brzostowica], to wreak similar judgments.

In the interim, however, the Krynki police chief, who escaped to Sokolka, managed to call for help from the district governor in Grodno. When the army delegation reached the town two days later, they found the local youth in formation on Sokolka Road, armed with revolvers, metal rods, and axes. Even girls were standing at the gate, armed with stones.

The army captains entered into negotiations with the rebels, and promised not to harm anyone if they dispersed. These negotiations continues until the district governor himself arrived, with the regular army and infantry, who had been housed in the Yenta Beis Midrash. Now they decreed a state of emergency in town. Approximately 200 of the participants in the revolt were arrested by the police, who were assisted by spies and informers from the officials and residents, some of whom regarded this as an opportunity to extort “hush money.” (After the workers recovered from these persecutions, they took revenge on the most murderous of these slanderers, and two of them were even taken out to be killed.) The prisoners were hauled to the prison in Grodno and placed in suffocating isolation cells. They were only freed in October of that year, with the government “manifesto” and amnesty that was declared in its wake. Some organizers of the revolt, including Niumke Frydman at that time, escaped from town. Some immigrated to America.

Disappointment and Setback

The revolt in Krynki concluded . The Bund organization was weakened, and its existence was no longer felt for a period of time. A mood of disappointment of helplessness pervaded amongst the workers. The intelligentsia was scattered, and reactionaryism reared its head. A “brotherly society” of manufacturers was formed in 1906 for the struggle with the workers. The organization of tannery workers was disbanded in 1907 due to the indifference of the workers. A recession hit the hide manufacturing, and the wages of the “wet” workers were reduced. The economy of Krynki was badly affected, and “Were it not for the support of the loan and credit organization, many small-scale businesses would have gone into crisis” – writes the teacher-activist Avraham Einstein in Hed Hazman on June 27, `1909, “However, the situation of the hide merchants improved lately, and the demand has grown.”

He writes in a second article in the same newspaper, from August 8th of that year, about the spiritual-cultural situation among the workers in the town: “The boredom that took hold of many workers in Krynki after the days of the revolt brought them to disillusionment and forced them to seek something to spend their time. Some of them founded the Tiferet Bachurim organization. They study a section of Ein Yaakov and Talmud every day between Mincha and Maariv from the mouths of the Yeshiva lads. Some of them spend their time reading American literature in Yiddish, especially the thick novels that shake up the nerves. The intelligentsia busy themselves with reading Russian books.”