[Pages 139-142]

A Quarter Century (1914-1939)

In the First World War

by Binyomin Shloymeh Zusman

(Benjamin Solomon Sussman)

Translated by Moishe Dolman

Donated by Jane Cooper

“The Redeemer”

The savage war had been raging over the world for a good few months. It had been said, and the newspapers had written, that the German was moving closer and closer to Brisk [Brest-Litovsk]. Now fighting had broken out in Brisk. All of a sudden (I think it was on a Thursday morning) we detected the sound of the first German airplane. Everybody ran out into the street, fixed their gaze upon the sky and – yes! – we saw that something small, perhaps like a big bird, was flying in the air and making a frightful noise. We beheld this bird-of-prey for no more than about five minutes. Then it disappeared somewhere in the sky. This served as a signal for everyone that we had to do something fast – run away, hide – because a fear had come over us all that at any moment the war would be at our doorstep, at the Horodetz Dnieper-Bug River. But where should we run? And how? All at once the whole of Horodetz began to run to the railway station. Here is why: The Russian regime had issued an arrangement, according to which it would transport for free on the train those who wished to escape deep into Russia and thus avoid the oncoming Germans. So practically all the gentiles who lived in our little town of Horodetz packed everything they could and made their way to the train station. And because they could not take along their horses and wagons they sold them dirt-cheap. Therefore everyone ran to the train station to buy these horses and wagons. I got wind of this situation, and I also ran right away to the train station. I purchased a small white horse that was a bit lame, together with a nice wagon which even had four functioning wheels. And I came home. At that time my father was in Moscow, where he had gone to undergo treatment on his ailing legs. My sister Babel and my brother Yudl had already been in America for a few years. My brother Yisroel [Israel] was a soldier in the Russian army. All of Horodetz packed up its belongings, and so did my mother and I. We gathered together a little bedding, clothes, a chair and a small table, tethered the cow to the wagon with a cord and set off down the road. No sooner did we get out onto the highway that leads to Antopol than we were halted by the Russian police. No civilian wagons were allowed to use the highway, because the road had to be kept free for the army, which ran like locusts to the front and from the front (mostly the latter). So we got down off the highway and started to ramble through fields and various unfamiliar roads. Because of this situation there formed a long line of hundreds of wagons from Horodetz and vicinity, moving, speeding with no destination, hurrying to find a hiding place out of the line of fire.

After eight hours of trudging through the strange fields and roads, we arrived in Antopol. Following a brief discussion we decided to go no further. A lot of people continued on, but we stopped here. We got to work right away: I dug a pit and buried the few worldly possessions we brought with us. We then set out by ourselves with the horse and wagon for a spot a few versts away from the city, where we would wait until after the Germans entered. It had become impossible to remain in the city. Everyone had run away. On the field there were literally thousands of people with their horses and wagons and cows. Thus we “sat” there for three days and three nights. The terror and grief we went through at that time are not easy to describe. We would lie at night in the fields, and the artillery fire would pass right over our very heads. The Czar's soldiers would always come to us and take away young men and their horses and wagons for the army. However, because our little horse was a bit lame, they didn't take it. On the last night, I think it was a Wednesday, we could see how all of Horodetz was aflame. Then we saw that the area where the train station stood was burning, and we could hear terrible explosions. As such, we understood that help was truly imminent. In other words, we would soon be rid of the whole Czarist order, and the redeemer, the German, would come in. In the last hours of the final night it became very quiet. A deathly calm ruled over the whole horizon, and when day broke we caught sight of the first German soldier, riding wildly upon a horse. He rode amidst us, the hundreds of people standing with outstretched hands and open eyes. We followed every gallop and every leap of the horse which bore this proud German. “Russky no here? Russky no here?” he shouted continuously. Then the German rode quickly off, galloping away. A little later more and more Germans arrived on horseback. We all truly rejoiced and congratulated each other. Everyone felt that finally, thank God, we had been liberated from the Czar and that we now had with us the good, fine friend of the Jews: the German.

Under the German

Upon our return home, we witnessed the great catastrophe which had befallen Horodetz. The town had practically been consumed by fire. Nevertheless, a few Jewish houses, and even more Christian houses, had remained standing. Our own house was also still there. The greatest wonder concerned R' Arn-Yoysef [Reb Aaron Joseph] and his wife Shifra, two old-timers and a dear couple, who had not left the town. They were the two people who quite literally “sat through” the crisis and survived. They had hid in the end of the pipe which was situated at the post office.

There now began very difficult and frightening times. We were a community without life: no stores in which to buy something, no doctor, no tailor, no shoemaker, no House of Study and – let there a separation between the sacred and the profane – no bathhouse. Moreover, the houses that did remain standing had been damaged. But what could we do? We still needed bread to eat! So it was truly a miracle that now was the end of the summer, the time to gather the produce of the field; and whereas the Christians of the town had all left for the farther reaches of Russia, all of our brethren, the children of Israel became farmers. We went out into the fields, cut grain, dug potatoes and even cut hay for the cattle and horses to eat. And in this manner Horodetz accustomed itself to a new, difficult but honest life. Horodetz Jews from that point on took to the fields: They tilled, sowed and harvested. Horodetz Jews (as did those of other towns) became Jewish peasants, toilers. They tilled the fields and worked well. The little boys, yours truly among them, would go out bright and early (even before there was daylight) to bring the horses from the pasture, harness them to their wagons, set up the ploughshares and… it was off to the fields! True, it was difficult: at the beginning we weren't familiar with the techniques of the job, and therefore Horodetz Jews had to work harder than experienced peasants. But we worked diligently. From this we had subsistence, and there would still remain something to sell so we could make a few roubles. As the saying goes: “Those who sow in tears shall reap in joy [Ps. CXXVI: 5].” However: “Man does not live by bread alone [Deut. VIII: 3].” We needed clothes, we needed shoes. But there was nothing from which to make them and nowhere to buy them. We went around barefoot and in rags. Still, as the saying goes: “a Jew copes,” and when they need to and when they must, Horodetz Jews can do anything. They started to dye, and made dresses, blouses, pants and so on. In this manner, little by little Horodetz clothed itself. But footwear? You obviously can't dye linen and turn it into a pair of boots! But we found a means: The German had developed a desire to unearth all his fallen soldiers from the battlefields around Horodetz and bring them for burial in one place near the church. German gendarmes would (violently) take Jewish youth, would go out with them into the fields, find the dead German soldiers, dig them up and bring them for burial in Horodetz (according to the procedure appropriate for Germans). Naturally, no one was eager to do this lovely job, and as soon as we would see the gendarmes we would go into hiding. This took place nearly every day over a long period of time.

A few weeks later we started to see individuals going around in new boots, in good shoes. What was this? From where? Then we found out that those who would go to dig up the dead Germans would remove their footwear, which they would bring home, clean with kerosene, alter and put on. When we witnessed this, we no longer hid from the gendarmes: on the contrary, we went out to meet them face-to-face. Can you believe it? Good boots, good shoes – and German yet! And from a dead German, to boot! And in a little while I also had a pair of good boots.

I become a policeman

They had begun to take our young people for forced labour. I was in the group that was sent away to the Nuretz Forest, not far from Kamenetz-Litovsk. There we would chop down trees, saw them, carry them out of the woods and load them onto wagons (probably bound for Germany). It was winter; we were quartered in an abandoned village. The houses were empty; there were no windows or doors. We slept on straw. Bright and early, when it was still dark, we were awoken and – it's hard to believe – quite simply chased out to work. Our nourishment consisted of one two-and- three-quarter pound bread every three days, black coffee without sugar in the morning and warm water – they called it soup – for lunch. In the evening, it was once again black coffee. That was all. It doesn't take long to get sick from such a life. Well, I became really ill and developed a high fever. My comrades decided that one person should not go to work so as to take care of me. However a German, may his name be blotted out, charged into the house and gave his almighty command: “The young one (that is to say, me) can just die quietly, and you (my caregiver) can just go to work!” But I tricked this German: God took care of me and I got better. Having slaved away in the woods for about two months, some friends agreed upon a plan of escape from this camp. We hired three wagons, driven by local Christians who knew the forests well, and in the middle of one night we made a break for it. It was a frightful and risky undertaking, because had we been caught they would have surely shot us. But we arrived unharmed in Kamenetz, and from there good Jews sent us over to Horodetz.

From the camp they telephoned the Horodetz commandant about this incident. At that time Yirmieh [Jeremiah] Shub was living in our house together with his family. He was at that time the burgomaster and was friendly with the secretary of the kommandantur. So he advised me to act sick, and when the police came to “take” me, they found me “seriously ill” in bed. Okay, but then what? Once again Yirmieh Shub came to my aid and arranged that I should become a translator and a policeman. The next day I was already wearing a stamp taped to my arm, indicating that I had been appointed a policeman by the commandant. So when the German regime needed to take someone for a job, or a horse and wagon for a day's work, or some eggs or butter, we, the Jewish policemen, had to tell this one or that one to go, travel or bring – according to the order. This was not pleasant work, but we did it honestly.

Once, on a Sabbath morning, when I checked in to the kommandantur, the secretary ordered me to shine his shoes. I told him that this day was our Sabbath and so I could not do it, whereupon he lifted up his right hand and let it fall across my face. That was too much for me to swallow. What was the meaning of this? Wasn't I supposed to be some kind of a policeman? An interpreter? I tore the tape from my sleeve and threw it in the secretary's face and – finished! He cursed me and I left and went home.

Lodging and Justice Society

It was harder for the Germans to subdue our tiny town of Horodetz than the big fortress-city of Brisk (Brest-Litovsk). For several days stiff and bloody combat was waged around Horodetz, and when the Germans at last entered the town, Horodetz was already three-quarters burned and laid-to-waste. Many inhabitants had escaped deep into Russia. The life of those who remained was terrible. There was not enough food to eat or clothes to put on. When winter came, the situation became even more frightful, because there was nowhere to buy anything and even had there been, there was nothing for which to shop. The houses were cold, because there was no heat with which to heat them.

Living in such circumstances, many people in Horodetz became ill with typhus. The situation became even more horrible because there was neither doctor nor dispensary.

As is well-known, this illness is contagious, and hence not everyone wanted to be around a sick person. But the ill needed day-and-night care! People died before their time, and we were powerless to help. Then, in those difficult and frightful times, the youth of Horodetz heeded the call. We convened the boys and girls of the town and discussed the horrible situation and what we could do to help those who were suffering. After several suggestions and opinions we united around one plan: to found a [Free] Lodging and Justice Society [Yid./Heb.: liness-hatzedek;]. Our work consisted of the following duties:

Every day we would gather milk, butter and other necessities for the afflicted families. Every night two people from Lodging and Justice would tend to a sick person for the entire night, thereby freeing the family members of that individual to go and rest up and sleep for a few hours, which for them was an urgent necessary.

This noble work was accomplished by fifteen and sixteen year-old boys and girls. Thanks to them many people in Horodetz were rescued; it is to these boys and girls that they owed their lives.

Cultural Work

The years of German occupation were difficult and frightful. People went about worried, working very hard for a piece of bread. But our new rulers gave us none; their motto was: “sheli – sheli, v'shelkho – sheli,” (i.e., what's mine – is mine, and what's yours – is mine) [Ethics of the Fathers, V: 13].

It was winter, the house was cold, and our stomachs were also not totally satisfied. Our hearts were sad and the long and boring evenings dragged on. There were no schools or libraries where one could learn something or read in order to forget a little the difficulties of daily life. So the few older and more learned among us organized evening courses.

The “Shkola” (the Russian school) happened not to have burned down and – because the Christians had all run away to Russia – no one was using it. So we gathered there several times a week. Young people like Shloymeh [Solomon] Podolevsky, Yeshayeh [Isaiah] Elman and others would give lectures and the young people would discuss their talks. In this manner we spent several warm cultural hours in the cold winter evenings.

A short time later, many of the inhabitants of Horodetz returned from their wanderings in Russia and my brother Yisroel [Israel] came back home from the Russian army. It was truly under his leadership that a drama group and a choir were organized. It was then that we staged Scattered Far and Wide and People by Sholem-Aleykhem [usual English spelling: Sholem-Aleichem], as well as other short plays, and we sang Jewish songs heartily and with gusto. Thanks to this revival life became a lot more interesting, bright and hopeful.

[Pages 143-144]

The Economic Situation

By S. Podolevsky

Translated by Hannah Kadmon

[Translator notes in square brackets]

On the whole, the inhabitants of Horodets were store-keepers, craftsmen and clergy. The store-keepers did business with the local farmers but also with farmers and Poretzes [Poretz = a gentile landowner; lord] in the surroundings. The craftsmen also worked for them.

This was the case until WW1. The war brought about a violent upheaval, destroying the old way of living, not bringing forth a new one. Thus, the shtetl remained neither here nor there. Located strategically next to two tall banks of a river, it became a battlefield between the Russians and the Germans. The canal changed hands between the two. The shtetl was almost totally demolished. The Jewish houses were burnt down, especially those in the center of town.

While the battle was raging, the Jews ran away to Antipolye, and when they returned, they found a pile of ashes in place of their houses.

The wooden bridge was burnt down and a temporary bridge was placed above the canal. The iron bridge was broken and the rails of the railroad protruded upwards.

The whole region which had always been full of life looked like a valley of devastation, destruction and death. The Jews who had returned and found their homes burnt down, started settling in houses that had belonged to the gentiles. All the gentiles fled with the retreating Czarist-Russian army which was unwilling to take the Jews along with them. So, the Jews found empty gentile houses and barns full of wheat.

When the Jews settled down a bit, they let the surrounding villages thresh the wheat. Many Jewish families who were driven away by the Germans arrived from Brisk [Brest]. The German evacuated Brisk from all civilian population and settled them in the surrounding shtetls. The Jews prepared themselves with food for the first winter.

Spring arrived. Since the whole gentile population - including the land-owners for whom the Jews worked - was gone, the Jews started thinking of farming and attending to the neglected gentile property. Something happened worth noting - something that never occurred not only in our shtetl but also in the whole surroundings.

Jew became farmers - cultivating the land. Former teachers, store-keepers, shoemakers and tailors held the plow and became farmers not only excelling in their work done on the gentile's farms but even outshining considerably the work of the gentiles. Later, when the gentiles returned, they did not recognize their farms and shrugged their shoulders with astonishment at the Jewish labor and diligence. It was amazing to watch Khayim, Moshe, Yosl and Binyamin behind the plow and also mow the hay as though their fathers and grandfathers were born and bred farmers, and to watch Khana, Rakhel and Sarah dig out potatoes, cut the wheat and bundle it as though they had been doing that since the creation of the world.

Some Jews, during the few years of the German occupation and later until the peace treaty between the new Soviet Russia and Poland, became in fact very rich as farmers. They were able to own a few horses and cows so that they did not only work on the farms belonging to gentiles, but also cultivate waste lands of the poritz's court.

Later, when the gentiles returned they did not know how to thank the Jews who attended so well to their farms. On those farms of gentiles not attended to by the Jews, the buildings deteriorated and wild grass covered the ground

The new way of life continued for five years, 1915 to 1921. In 1921, after the peace treaty between Russia and Poland, the gentiles moved back to Horodets and the Jews left the farms and started engaging in post-war occupations. However, things were not like before. A great part of the farmers did not return. The river that nourished the shtetl half year round - was inactive. The people on the other bank of the river, who used in previous years to send lumber abroad, belonged now to Russia and the new Soviet Russia was not interested in sending lumber abroad. The Polish government which occupied our area after the war was not friendly to the Jews. Jews started suffering hunger and their situation was worse than at the time of the war.

True, support came from America, but it was slight. The Jewish population of the shtetl and the surrounding villages conceived the idea that perhaps they should turn to the Poritz of the shtetl-previously a Russian and now a Pole, who had come back after the war - hoping that he would let them cultivate the desolate part of his estate. They would pay him either in money or in grain.

I, the writer of these lines, and some other home-owners in the shtetl solicited the help of IK”A in Warsaw to send some messengers to talk with the Poritz because he did not want to talk to us. He even launched his dogs at us when we went to talk to him. [IK”A = Jewish Colonization Association founded by the Baron Hirsh to re-settle Russian Jews]. The IK”A sent an agronomist, a young man, a graduate of a Polish school, who contacted the Poritz. Later, we joined him as well. At the end of an exchange that lasted an hour, we concluded that nothing would come out of the negotiations.

I left for America in 1925, met our landsmen there and told them everything. For several years they did all they could and quite often sent over money. However, it was a drop in the bucket. [In Hebrew and Yiddish: “A handful does not satisfy the lion”]. The situation in Horodets grew worse and worse. The letters from there were more and more tearful. However, what could we do? A ladies Auxiliary was founded to raise money and with the help of this association a gmiles-khesed [loan without interest] for Horodets was established.

After the disintegration of Poland in 1939, The Red Army occupied the shtetl and happier letters started arriving, with a great deal of hope. We thought that this would end all troubles. However, now our poor shtetl is dead and desolate and who knows whether it will revive one day.

[Pages 145-146]

The Transition Period

by Binyamin M. Israel

Translated by Hannah Kadmon

[Translator notes in square brackets]

A.

The Germans ruled Horodets for more than 3 years. Those were years of hunger and degradation. However, they were nowhere near the days when the Germans withdrew from our region, when the whole region from Brest to Pinsk was, for several months, in 1919, a totally no- man's-land. Those who could – took control of the region, looted, raped, beat and killed. Our region changed many bloody hands: Petliortzes* Balakhovtzes** and other gangs of robbers fell upon those poor neighborhoods and especially upon the poor wretched Jews who survived the war and its painful aftereffects.

* [Petliura was a top Ukrainian commander fighting the Red army, was defeated and his followers, –Petliurites -, carried out pogroms against the Jews.]

** [ the volunteer army of General Bulak- Balakhovitch, the leader of the White Guards fought the Red Army and “helped” the Poles.]

Not a day passed without saying prayers for the approaching night, and in the evening they said a prayer for the next day. They did not know where to hide and did not have anything of worth to hide. Their life hung by a thread. That gave rise to the idea of organizing a self-defense unit (“Sama Obarone”). The youth got hold of some rusty revolvers, shot-gun and some daggers. A farmer, an acquaintance, promised to get a good German gun for them. Israel Zusselman, who had just returned from the war, was entrusted to organize the youth and teach them how to use weapons. The sons of Aharon Asher, Menashe and Abrem'l Rodetzki, Shlomo Lieber, Yeshaya Alter son of Shefe, Nyomke brother of Israel, Shlomo Burshtein, Naphtali son of Moshe Aharon, David Kaplansky and a few others joined this self-defense unit. Their meeting was, naturally, very secretive and they hardly knew the whereabouts of each other.

Every night 2 members patrolled. One would walk around in the market and the other - in the main street. They knew quite well that if an armed band attacked Horodets they were helpless, because what could they do, Heaven forbid, with a rusty revolver and an old gun? Still, this organization lifted the moral and strengthened us. It also granted us a measure of peace-of-mind. The knowledge that the “young men watch over them” calmed down our Jewish population,

Horrible news arrived from the neighboring shtetls and villages, about the “accomplishments” of the murderous-gangs and how they treated the Jews. There was fear of something else: that our “good neighbors”, the gentiles, would betray us to the Poles who would then arrest us for holding weapons and would not be content with pinching our cheek…All members of the self-defense unit lived in fear of the two dangers.

In the middle of 1920, many members of the self-defense unit, among them Israel Zusselman, left for America. A few weeks after their departure, Balakhovtzes invaded Horodets, entered Itzik'l's house searching for his son, Israel. When he told them that his son had left for America, they did not believe him. They told him they would return the next morning and he must hand his son over to them. That night, Itzik'l burned all the books, manuscripts, drawings, photos and all that had some connection to his son, and went to Hannah-Malka's house where she hid him in bed under a quilt. He lay there until the Balakhovtzes were gone. After a couple of days they came again. When Minye, Itzik'l's wife saw them from afar, she immediately let her husband lie on the floor, covered him with a cloth and arranged lit candles around him. When the bandits came in she told them that Itzik'l had just died. The bandits wanted to stick Itzik with the gun to see whether he was really dead. His wife fell on her knees and begged them not to do so, as it would disgrace the dead. After begging for a long time, they left.

That episode illustrates the chaotic situation of the Jews of Horodets in those horrible days.

Soon, some “order” was reinstalled. The Poles took over the region. Alack to that “order”! Wild murderous soldiers from Poznan (“poanantshikes”) and from general Haliyer's army (“haliyertshikes”) landed in Horodets and beat and killed whoever was within the reach of their hands, and as a joke – bloody joke – they used to shear, that is: tear, half a beard and the victim had to wear a bandage over half his face until the half beard grew again, as in the case of Shimon Izik and Simkha Yudl.

B.

Things cooled a bit. The Poles started restraining their wild soldiers who were freedom-drunk. However, war broke between the Poles and the Bolsheviks.

The new threat was now the capture of Bolsheviks. The Poles considered every Jew a Bolshevik. Many Jews were killed because of this and many, many, were scared to death.

[Editor's note: see for example the article about “Hershel the Teacher” and “The Town Joker”]

In the summer of 1920, when the war flared and the Poles started fleeing from the Bolsheviks, the Jews were completely abandoned and the Poles looted them endlessly.

When the Bolsheviks conquered our region, the middle-class Jews did not have a ball [in Yiddish: “did not lick honey”]. They confiscated property, they arrested for violating the Bolshevist rules and so forth.

They could stand all that until the real shooting. Bullets flew above their heads and heavy shot from all directions. Horodets was a strategic spot because of the river. The Poles were on the Kobryner side and the Bolsheviks – on the other side.

That was before Rosh Hashanah. About 10-15 Jewish families moved into a cellar in a farm, where they used to make “Swiss”-cheese. They simply filled the whole cellar and could not even stretch their legs. They hid in the dark cellar for 12 whole days, till after Succoth, when the Bolsheviks left. During those terrible 12 days Leibe Roytkopf of the goat-farm was killed by a bullet when he once came out of a trench. Some people became sick out of fear and died.

It should be noted that in this very ghostly time, several Jewish family gathered a minyan [at least 10 men] to pray on Yom Kippur with a scroll of Torah and all the features of this holy day.

Thus they suffered until the fighting was over and the Poles, once again, ruled our region and again bullied the poor Jewish survivors of Horodets. However, not many Jews remained. Those who could afford it - immigrated. Some immigrated to The United States, others – to South America or to the land of Israel. Those who remained in Horodets were poor, helpless, Jews who did not have relatives in America or did not possess the courage to run away. They stayed in the shtetl where they were murdered by the Hands of the Germans, may their names be erased!

[Pages 146-147]

The Pole

by Yudl Greenberg

Translated by Hannah Kadmon

[Translator notes in square brackets]

The year 1921 marked the beginning of a new epoch in the history of Horodets. After the cruel war between the young Soviet government and the young Polish Republic, a peace treaty was signed in Riga on the 18th of March, 1921. Horodets finally remained under the Polish rule. Horodets, like the whole region, was destroyed during the battles. The fields on the farms were deserted and the cattle were slaughtered. Most houses were in ruins and those that remained were badly damaged by shelling. All pieces of furniture were also victims of the war; they were used as firewood.

The bridge which connected the “market” with the “street” [Main Street] was blocked. Horodets looked like a skeleton of a town without a sign of life.

Very slowly, those who had fled deep into Russia, because of the Germans, started coming back. Those who were lucky to find their homes started repairing them to make them fit to live in.

The returning Jews had it really bad, because they had no fields to sow and they did not bring with them any treasures of gold. They had to adjust to the circumstances and start from scratch.

The population of Horodets consisted of two groups: White-Russians and Jews. The few Polish residents were: the poretz [gentile land-owner] for whom the farmers worked, A Polish teacher and 3 policemen. These “dignified” Poles treated the residents of Horodets as their servants. There was an unwritten rule that when someone met the above mentioned Poles, he had to take off his hat to him. If, God forbid, someone forgot to take off his hat – he was in trouble. Hitting and insulting for every trifle was a common matter. The Poles applied their rule especially to the poor Jews.

Even though Poland was officially a republic with equal rights to all citizens, this was not so in reality. There was freedom of religion but no freedom of press, or assembling. They permitted social recreation and cultural assemblies. However, to get a permit it was necessary to send a request to the governor. The permit was not always granted.

Political convening or rallies were absolutely prohibited. Even before elections, assembling was not permitted. A Zionist meeting was also absolutely prohibited even though the Zionist Organization was legal in Poland.

A mere stage-performance without any implied political meaning was also forbidden. Once, when the youth of Horodets wanted to stage a play, some Polish policemen appeared and broke up the gathering.

This autocratic regime was the reason for the rise of dissatisfaction among the non-Polish population, especially among the White-Russian gentiles. They preferred to belong to their motherland Russia. Therefore, there were communists among the White-Russian youth. When the Polish government tracked down a communist – he did not get away alive.

The Jewish youth of Horodets gave vent to their protest against the tyrannical Polish policy by preparing for Aliya [emigrating] to the Land of Israel, to live there as Jews.

The goal of the Polish government was to “Polanize” the whole region. [transform the whole region to be completely Polish], at the same time sowing anti-Semitism wherever one turned. To reach their goal, they established a Polish public-school where all the children had to learn Polish as a means to make them absorb the Patriotic spirit of the Poles and also their hatred of Jews.

Here is an illustration: the Polish teacher pointed to her four-year-old son two people walking in the street, remarking: “That one is a noble man and the other is a Jew”.

Naturally, the Jewish children could not attend this school for long with this kind of education very soon left the Polish school. Some travelled to Brest to attend the “Tarbut” schools and others left to study in yeshives [Religious institutions of higher Talmudic learning].

* *

*

At the end of 1928, when I left Horodets, many Jews had already recovered. Many rebuilt their life from scratch, and lived a productive Jewish life with the hope for a brighter future for the community and for each person. Unfortunately this dream did not materialize. It was shattered and a painful tragedy befell our shtetl. Only a single Jew survived - the only living witness to a community that was erased and would never live again.

[Pages 148-152]

My Visit

by Israel Zussman (Israel)

Translated by Hannah Kadmon

[Translator notes in square brackets]

In the summer of 1927 I went with my wife on a belated honeymoon trip to Horodets. Since my father did not have the good fortune to lead even one child to the khupe [canopy of marriage ceremony], I wanted to let him meet at least his first daughter-in-law.

When we arrived in Warsaw from Paris, I called my father from the telephone of my wife's relative. The telephone in Horodets was in the post office and it took about six hours to get us connected. When I finally heard my father's voice, his first words were: “...שהחיינו” [Shekheyonu vekiymonu vehigionu lazman haze = benediction over a happy occurrence: “for keeping us alive to reach this occasion”]. He spoke hurriedly and his voice quivered. Since I, too, spoke very fast – we understood each other very well.

|

|

“The Community”

First row from right to left: Ruth and her husband, Israel Zussman; Sirke, Shimon Izik's daughter.

Second row: R' Asher David the shoykhet [ritual slaughterer]; R' Itzik (Israel's father); R' Shimon Izik; R' David Moshe Savitzky.

Standing: right: Minyeh, Reb Izik's wife; left: Khashe, R' Shimon Izik's step-mother. |

In the morning we travelled to Brest where we met in the terminal Avraham-Khayim Kostrinsky (Motye's son) with his daughter, Noakh Polyak with his wife Ester (Vinograd) and Makhle, sister of Tzivia Greenglass. Since we had to wait a few hours for the Polesian* train, I could spend some good time with them. They said that in all terminals we would meet acquaintances because all knew of our arrival. [Polesia = a marshy region lining the Pripyat River in Southern Belarus]

From Brest, the ride was more familiar. Here is Zshabinke and here we are already in Kobryn. Many acquaintances, many kisses, exchange of questions and the few moments pass very quickly – the train moves on the way to Horodets… My face is glued to the window. The train passes quickly along familiar fields and here is the village Kamen; I devour the whole panorama like in a dream. The cemetery can be seen now from afar. My eyes are tired, my heart palpitates louder – the wheels pound also as if they want to compete with each other … and I already see from afar the top of our galovnik (pigeon coop). I want to have a good look, but we are already on the bridge. Trakh-trakh, tiyakh-tiyakh – and we are already near the brick-yard. The train slows down and I can see the terminal from afar. Wow, how shrunken it has become. All at once the train stops. I run down hurriedly and I see unexpectedly how the policemen pay their respect to me. (Later I found out that they had read in the papers that I was supposed to draw a picture of their president Pilsudsky). My eyes search swiftly for my father and I see him pressed against the wall with stretched arms. The first words that he uttered were: “לראות את פניך לא פללתי” [Hebrew: “I did not believe I would see your face”]. We let a tear fall, he kissed his first daughter-in-law, and together with our good-hearted aunt Minye (my father's second wife) we sat on Aharon-David's cart which looked very festive with fresh hay spread all over – and forward to the shtetl.

Many people and children came to the terminal to welcome us. More than any of the folks, my friend Motl, son of Khayim Nissan (Vinograd), caught my eye. He was riding a big horse. On the way we did not talk much – only eyed each other and kept quiet. Approaching the shtetl it seemed to me as if the houses had become smaller. When we arrived at our own house, the street was full of people. The welcoming celebration was beyond description and we did not know what to say or ask first. We sat and talked until dawn.

In the morning the Polish commander arrived to pay his respect and ceremoniously kissed my wife's hand. He was very cordial. It seemed that even the old Poland had a great deal of respect for an American who was assigned to paint their president.

Later on I walked about the shtetl which looked different than in 1920 when I left it. The streets were nicely rebuilt, and there was also a new besmedresh [study house, where people used to pray as well]. Alter, the blacksmith, built a nice house and new houses on both sides of the besmedresh. Even the bridge was new and longer. The market place was also rebuilt and Khayim Nissan's house was the most beautiful of all houses in the shtetl. Still, poverty remained the same.

I walked to the cemetery to bow my head at my mother's grave. I did not notice that Alter the blacksmith was standing in a distance saying quietly “אל מלא רחמים” [prayer on a grave]. The cemetery did not shrink in size. On the contrary, it grew in size. Many new graves had been added – with or without tombs. In the middle of the cemetery, was yet to be found the “tent” of the old Rabbi as if watching over the other graves.

In former years there were two places to pray in: the Hassidim prayed At Shepsl, in the “wall” [house built with brick] (Stolin and Kobryn Hassidim) and the Misnogdim [opponents to the Hassidic movement] and the “gasser” [ordinary people] prayed in the new besmedresh. On the first Sabbath I prayed with the Hassidim. They honored me with reading the maftir [the reading of the lesson from the Prophets] and, poor me; I had to read the whole lesson. This same thing repeated itself the next Sabbath in the besmedresh. The first Sabbath, the shtetl sent us drinks like for “seven blessings” [said at a wedding] (at my father's it was virtually a wedding). A child would come with a bottle of beer or wine, or a plate covered with a cloth like shalakh Mones [the ritual sending of baked and prepared sweets on Purim] and would say: “welcome to your guests”… The next morning, Khayim Nissan told us that people bought all the drinks in his cellar…

My good aunt Minye wanted to cater to her guest and to all my requests to cook the plain local Horodetser krupnik [barley soup] she answered: “Leave me alone! For such a guest a mere krupnik soup? You will eat at my place a roast…” In short, she roasted the roast for such a long time, till I fell sick. Then she cooked the krupnik.

During the two weeks of my stay in Horodets, I visited almost every house in the shtetl. (In many houses they treated us to tea and varenye [jam]. I paid a visit to the good Rabbi R' Ari' Greenman who lived in a modest room in what used to be Simkha-Yudl's house and was now owned by Yankl the mason. I visited Uncle Asher-David the shoykhet [ritual slaughterer] who lived in Izik Izrael's house but his heart was in the Land in Israel. He actually emigrated there and died there at the age of about one hundred. I visited my Rabbi and scholar R' Shimon Izik who always longed for big towns and craved for knowledge but remained in Horodets. I had a conversation with Tuvia the shoemaker, the oddball and “town-joker”. I talked to Shlomo Burshtein - teacher, idealist and bundist [follower of the socialist Jewish labor party] who had become a shop keeper - while he was weighing cereal. He really pondered about the world's hardships and dreamed of world-redemption. I talked to Yaakov Polyak, the eternal fashion- shopkeeper who regarded taking measures as a sacred procedure. I paid a visit to Alter the smith, the pubic leader, active in the community, a member of Khevre Kedi'she [voluntary burial society] “second in importance”. I did not miss seeing shepsl the Stoliner [Hassid] always joyful, a wide smile on his face, who used to help the fathers sing Sabbath songs. I also had an “interview” with Yankl the mason who used to laugh at the world and loved people, mainly the poor. I also visited Khayim Nissan Vinograd, of short stature but with a big heart, a big family and a comfortable house, well-established like an oak, and many good children. The modest Motye, the Rabbi with his wife, who lived in our house, asked many questions about America because he had one foot already there.

I talked to many people in Horodets from all social classes: workers, toilers, shop-keepers, and intellectuals. I talked to all of them, asked about their life and heard from all of them the same response: “Bless America! This shtetl exists more than ever thanks to America”. There was hardly any family that did not have one of its members in America and only their kin's support kept them alive. The American dollars were to the people of Horodets like the manna to the people of Israel in the desert.

I spent time enjoying our fruit orchard and even the pigeons knew that an American guest was there and they flew about more happily than ever…

Everyone admired the American. An American was a man who knew everything, a man of integrity – and what not? It happened to me, as an American, to be chosen even as a judge and I was approached with a dintoyre [lawsuit before a rabbinical court].

Did I satisfy the two parties? – I don't know. There was enough shouting at each other. The shouts could be heard in New-York. However, when it ended late after midnight and I read the verdict, they drank lekhayim [to (long) life] and everybody was happy.

I became acquainted with the new Rabbi, R' Arye Greenman. He was a genteel person and a great scholar. He was a man with a good heart and the people of Horodets were lucky to have him in those days, gentle, very dedicated, always ready to help each person with counsel and in deeds. However, he hardly made ends meet. They used to say that he sometimes went hungry, very quietly, never complaining.

The two weeks ended swiftly like a dream. It was a great festival. The house swarmed with people and those who could not get in, at least peeped through the windows to catch a glimpse of the American.

My heart told me that this was my last visit in my birthplace, that I would never again see this shtetl . Therefore I wanted to inhale everything, to treasure it for later. I wanted to re-live my childhood and my early youth. I wished to go once again through all the places which reminded me of the near and far past. Therefore, I took a walk with my young friend Motl Vinograd to visit the “pakoy” [“hall”] where we held our Zionist concerts and performances after WW1 and now stood bleak and deserted. I strolled with Motl along the “batshvenikes” (the two banks of the river) to the sluice and walked through all the trails which awoke many memories of the good, sweet years of my childhood.

I had taken along my led-pencil and sitting on our open balcony I would draw many types that are about to vanish. I also took pictures of our small street and of the main street viewed from the bridge with almost the whole shtetl gathering there.

Time has come to depart. On a fixed day, I think it was a Sunday, we woke up quite early and around 6 o'clock we left the house. Israel Moshe's cart was already waiting for us as also many people who woke up early with us to say goodbye. We took leave in silence, kissed the neighbors, Yosl the mason and Motye with Uncle Asher David, Shimon Izik, Khayim Nissan, David Moshe, Aharon Asher and many more. Then we climbed to the cart. Then I stood straight and made motions with my hand as though gathering the whole shtetl to me and said: “Be well…” Tears rolled down my cheeks and choked my throat so I could not continue the sentence. I restrained myself from crying and asked Israel-Moshe to get moving fast. Viya! – He pulled the reins. The horse woke as if from a nap, cheerless and not in a hurry to pull himself from the place. Then we were on our way to the train station.

|

|

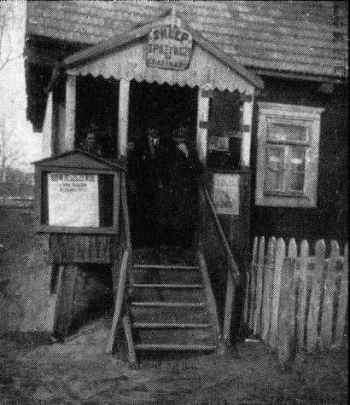

| The “Street” (after the First World War) |

In the terminal each of us took heart and made an effort to be joyful. However it was useless. So we deliberately talked about trivial matters at this important moment…

The train arrives. We quickly start to take leave of each other, hug each other, eye each other wordlessly and we swallow our tears…Soon I am standing on the steps of the wagon, take a good look at my father wishing to engrave his image in my memory.

Timeless scarce seconds – wish we could stretch them – but we hear a sharp honking and the train pulls in a sudden start from its place.

It tears my heart. I hear my father's “צאתך לשלום” [“leave in peace”] and “יברכך ד' וישמרך” [may god bless you and watch over you”]. My eyes are tired. I bite my lips in order not to cry. Now I see my father as if through a mist, leaning on his stick whispering a prayer.

He becomes smaller and smaller, shrunken, until he vanishes in space. ..

The train starts moving faster, wheels pounding noisily as if willing to drive away my thoughts.

I have the feeling that this is the last time I see my father.

[Pages 152-154]

The Pioneer Movement

By Bella Feinshtein (Israel)

Translated by Hannah Kadmon

[Translator notes in square brackets]

[Bella Feinshtein lived first in Kibbutz Shfayim with her husband Ben-Zion.

When the members of the Kibbutz split because of ideological conflicts, they moved to Kibbutz Ramat-Yokhanan and raised 3 sons. They both lived there until their death.

I knew both of them very well and loved them very much. Both were very active in the Kibbutz communal life. This translation is dedicated to their memory. HK]

[Akiva Ben-Ezra's commented as editor:

In addition to the article that covers in general the nationalistic revival in Horodets in between the two World Wars by Shmuel Hoyzman, we received this article by Bilhah [Bella] Feinshtein (Beyle, daughter of Moshe the blacksmith) from the Land of Israel. She is the only one left of her whole family. We offer this article because there are certain details and notes not mentioned in Hoyzman's article.]

* * *

I cannot remember the exact date when “Hekhalutz” [the Pioneer] was established in Horodets. However, in 1926 the members of “Hekhlutz Haboger” [the adults] decided that “Hekhalutz” must have continuity. For this goal they founded “Hekhalutz Hatza'ir” [the young pioneer] which included a few dozen members whose age was 13-15. In the shtetl, at that time, there were no Yiddish schools at all. All the children had to attend the Polish schools. However, their parents were imbued with the spirit of nationalism and therefore they saved every coin from their meager income to enable their children to learn Hebrew in the free hours from the Polish school. Lieber and Yaakov Adrezinsky helped them in this matter. Those two were also the teachers. Thus almost all the members of “Hekhalutz Hatza'ir” got the same education, knew Hebrew more or less, and were imbued with the spirit of Patriotism that enabled fertile and systematic work.

The work in the Chapter, and even later, when we were already in “Hekhalutz Haboger”, was always illegal because we did not have the sufficient means to rent a place and carry the work formally. All the meetings were held under cover. For each meeting we had to look for a new place. In summer – on the bank of the river, a few kilometers away from the shtetl, or in the forest or in the field. In winter –in one of the members' house, each time in a different home. Naturally, it made our work more difficult. The people on duty had to look for a place to gather the members.

Occasionally, when all was ready, the meeting could not take place for unforeseen reasons. For some time we used the name of the library which was legal, and which was founded by the same members of “hekhalutz” and sympathized with us. This was also not always possible because we had to get permission for each assembly.

I recall two illegal gatherings. The first gathering was held one summery Sabbath on the river bank. A police commander suddenly appeared from nowhere. He was a tall, broad shouldered gentile with a pair of red cheeks. He confiscated our “Bamesila” [=on the road] (a book about the land of Israel written by workers in the land of Israel) and other brochures and newspaper such as the “He'atid” =[the future] (a Hebrew newspaper that was published in Warsaw).

The second gathering was held in the “Tzigelnyer” forest led by Khayim Biletzky from Kobryn and the commander got wind of it and took us to the Police station. They beat some of us and warned the others they would be beaten too. The commander wanted to know who the leader was. From us he could not retrieve his name. Finally he found out his name and he succeeded to detain the man in Kobryn. The “Mored Bemalkhut” [Hebrew: rebel against royalty/authority] was caught. Only thanks to the League-leader in the Federation, Biletzky came out of it frightened but unharmed.

[Editor's comment: Khayim Biletzky was later a fellow worker in “Al Hamishmar” [a socialistic newspaper in Israel] and the author of a book of poems.]

The main activity was educational and cultural. Three times a week the members were gathered under the leadership of the two men mentioned above.

They taught us the following subjects: Jewish news - political and economical- and Zionist news. We also discussed various Zionist and Socialistic issues.

| A group of pioneers |

|

|

First row, sitting, from right to left: Abraham Vinograd, Chaya Kupriansky, Abraham Garber

Second row: Chashke Veisman, Yaakov Adrezinsky, Pelte Glatzer, Lieber Polyak, Yehudit Rubinshtein.

Third row, standing: David Rodetzky, the daughter of Hershel the chimney sweeper, Yaakov Goldberg, Feigel Greblovsky, Michal Helershtein, Genendil Vinograd |

|

|

Horodetser pioneers in front of

Moshe Ber Kupriyansky's house |

In time, some members joined us from rather poor families. They could not attend the Hebrew courses. We made efforts to make them feel part of us and we taught them Hebrew. Our means were scant. We had only the membership monthly fees contributed by a small number of members. So, we cultivated a garden and from the income we set up a small library at “Hekhalutz Hatza'ir”. The work in the garden was voluntary, but almost all members took part.

In winter we set up courses for poor small children who could not take private lessons and had to attend the Polish school. Some of us – Khaya Olchik, Yossef Mantak, Yehuda Greenberg and I – volunteered a few times a week for this purpose. The children acquired quite a lot during the winter.

Naturally, we also took part in the work of collecting money with the “Keren Kayemet” boxes. [the fund for buying land in the land of Israel], which was for us a holy ctivity. I went with Yaakov Adrezinsky to distribute the first “Keren Kayemet” boxes. I still remember very well with what joy some very poor women welcomed us. They gave away the last coins left from the scant savings that they put aside after hard toiling. Horodets became quite poor after the wars. Most of the families existed thanks to the support of their American relatives.

We also got together with friends from Antipolye and Kobryn. When we visited these members from the Center, we heard each time, how satisfied they were with our Chapter, saying that it was one of the best in the neighborhood. That was because of the two following reasons: First, the nationalistic education and second, the leadership of the two leaders mentioned above. Our aspiration, naturally, was “Aliya” [immigration to Israel] and “ Hagshama” [implementation/actualization]. However, actualization was entangled with many external obstacles and not everybody was able to persist in coping with them. Only a part of the members are now in the Land of Israel. I am the only one from our shtetl on a Kibbutz. The others are outstanding and productive members in this land. Lieber Polyak's yield is plentiful- our being here.

[Pages 155-162]

Under the Polish Regime

By Rabbi Shalom Podolevsky

Translated by Hannah Kadmon

[Translator notes in square brackets]

Between 1918 and 1939, until WW2, our tiny shtetl Horodets was under the Polish rule. The population included 50 Jewish families (about 200 souls), around 100 Belarussian families and 15 Polish families. All the Russians were farmers. The Poles were civil officers such as police officers, community officers, teachers, postal clerks, railroad officials, etc.

The Jewish population was composed of workers, shop-keepers, and small dealers. Our shtetl became even smaller and poorer as the result of WW1, and many wished to immigrate, or had already immigrated, to other lands because the Polish government did everything to embitter the life of the Jews, to oust them from their occupations in order to hand them over to the Polish farmers.

Thus the authorities very often issued distressing decrees against Jews. For example: The Jews had to pay very heavy taxes for their houses. They had to pay the Polish Poritz [the gentile land-owner] money for the piece of land on which the house, store or workshop was built. When someone was sick and could not be conscripted to the army, he had to pay special taxes all continuously. The Jewish worker had to pay taxes to get a permit to work. He also had to pay a high income tax to the government. The Jewish shop-keepers and the small dealers alike had to pay risk-taxes.

The Poles also introduced the cooperatives which could belong only to Poles. The worst decree was called “karte zshimitznitze”, without which one could not work. To get such a card, a Jew had to finish a trade-school or pass an examination and prove that he, his father and his grandfather and great-grandfather were born in the same shtetl.

The Jews in bigger towns found ways of getting such a card. Public schools were established and advisors and middlemen helped get such a card. However, in the smaller shtetles Jews had a lower level of education and it was almost impossible to get such a card. Thus work was gradually slipping off Jewish hands. Bitter was the fate of a Jew who managed to get the card or the permission to open a grocery store, but could not pay all the taxes. That is when the bailiff would come to execute confiscation - selling his quilt, his bed, his workshop and his sewing machine. When the bailiff arrived in Horodetz, the Jewish town-elder (Asher Mendel, the mason's son) would hasten to tell these individuals to hide everything. The poor people, pitifully, locked their houses, chased the cows, horse, calves and hens out to the fields, put out of sight their sewing machines and their beddings and hid somewhere until the bailiff left the shtetl.

When Hitler, may his name be erased forever, forbade the ritual of slaughtering in his evil regime, Germany, the Poles, wishing to imitate the Germans, also decided to forbid slaughtering, under the pretext that slaughtering is not humane enough and is a barbaric act. Their goal was to stop Jewish trade in meat, and in general to snatch the piece of meat from Jewish mouth. When a Jew slaughtered a cow with a slaughtering knife as the religious custom requires, not wanting to eat from a killed or dead cow, he could get 5 years in jail or he could lose his life.

In the bigger town one could get a piece of meat for a high price, because over there, the authorities allowed the slaughtering of a very small amount of cows. However, a Jew in a small shtetl, and especially a poor Jew, did not have any meat. Thus in our shtetl Horodets there was no meat and the small children did not even know what meat meant.

Itzik's shtiebl [a small Hasidic prayer house] was well known in the whole neighborhood because besides its being used for prayer, Itzik built a nice Hakhnoses-O'rkhim [Shelter/inn for poor wanderers]. He kept improving this inn from day to day. In summer, in Itzik's yard behind the house, grew some good fruit trees and the poor enjoyed them and blessed the landlord who had built the inn, not aware that this landlord was present and living among them.

Since the smaller and bigger shtetles around Horodets did not have any Hakhnoses-O'rkhim, poor wanderers planned to arrive in Horodetz for Sabbath. Every evening, poor wanderers and vagabonds, would come to Horodets. This changed completely the appearance of our shtetl. Hakhnoses-O'rkhim made our dear shtetl famous in the towns and shtetles of Poland, especially during the last years prior to WW2, when Hitler, his name be erased for ever, was already in power. Thousands of sick and desperate people, who fled the concentration camps, started coming to Horodets. Here, Itzik's Hakhnoses-O'rkhim was very helpful. When the displaced Jews rode the highway or on the train through Horodets, they would stop and rest in the Hakhnoses-O'rkhim.

|

|

A character from among Itikl's “guests”

(Drawn by Israel Zussman) |

The shames [attendant] in Hakhnoses-O'rkhim was Itzik himself. He was a sick man, and actually without legs, since during the last years his artificial legs wore out. Thanks to my father who mended these artificial legs and adjusted them for Itzik, he could still use them. Itzik himself used to say: “I walk to perform mitzves [good deeds] with Lieber's legs”. Itzik would be standing like Abraham our Father and performing Hakhnoses-O'rkhim [attending to his guests] from early morning till night. Itzik felt greatly honored when the guests used to call him “shames” even as they were angry and were yelling that the “shames” was not so good and that there should have been a better “shames”…

Thus the Jews of Horodets, despite their poverty, had to share their very little money and piece of bread with the poor folks of the Hakhnoses-O'rkhim. Every day, Horodetser Jews and volunteers used to go and collect money for an important guest and for the sick and wounded from other lands.

In 1938, I happened to collect money for a refugee from Germany. I had just come home for a Holiday from the Yeshiva of Mear and the Rabbi and a few Jews approached me and asked me to go on this errand. That was a short time before I departed for America. I did not feel like going because I knew how poor our shtetl was. I did not have the heart to ask them to donate from their meager money. My father was irritated and explained that I ought to perform the greatest mitzve - Hakhnoses-O'rkhim - and that everybody would welcome me with respect. So, I went along, having no other choice. My partner was my friend and cousin Rabbi Kalman Kupriyansky, Moshe Ber's son and Alter the blacksmith's grandson. I was touched by the fact that the folks greeted us with respect, handing out their alms and food and while doing so they blessed us for bothering to go from door to door.

In Itzik's shtiebl the prayer was conducted in the Sephardic version. Still, all the market people, Ashkenazi and Sephardic, prayed together, and even the Rabbi prayed at Itzik's because he lived in the market place. The older people from the market place also used to pray in this shtiebl every morning and evening, and even studied there a bit. Others used to sit there a whole day and study. On Sabbath and Holiday, all the people - young, old and even small children - went to pray in the shtiebl. While being there, the young ones used to snatch some rumors about politics and stealthily glanced at a newspaper. The young children used to play, yell and carry on and while this was going on the fathers and grandfathers watched with glee and joy the young “fruit trees” that were growing in our shtetl and would go on drawing their spiritual nourishment from the Horodetser tradition. They said: “with such good children that we are blessed with, our shtetl will never go under, a generation goes and a new generation comes. It is true we are old but our children will fill our place and our shtetl will continue to exist”.

In summer, Sabbath evening, people used to go into the shtiebl or besmedresh [the study house, where people used to pray as well] to read a chapter, and in winter – “Borkhi Nafshi” [prayer from psalms; “My soul blesses God”, etc.]

|

|

“The new besmedresh”

(Drawn by Israel Zussman)

|

Others used to browse through a page of the Gemara [part of the Talmud] or read psalms. There was also in our shtiebl a group for mishnayes [collection of post biblical laws; part of the Talmud]. Rabbi R' Arye Greenman used to teach mishnayes every Sabbath evening to the folks and those who had a taste for mishnayes would sit at the table to listen. Even the young used to listen from a distance while the lecture was on and posed a query to the Rabbi, to which he would answer with a great deal of affection.

Before my departure, before the war broke out, they were learning “Sanhedrin” [=one of the mishnayes dealing with capital offence laws and procedures of trial; also the name of the high court in the land of Israel of 70-71 wise men]. The Rabbi spoke about how they led a murderer to be executed, and even while leading him to the place of execution, if they saw from afar a rider coming towards them, they stopped and turned back and they didn't kill the man. Shlomo Burshtein, the shopkeeper, posed a query: “if the Sanhedrin has already found him guilty, why should they revise the verdict”? and the Rabbi explained that even for a murderer it is necessary to look for some virtue or credit. Even if a person killed but some virtue or good deed can be found to his credit, he should not be killed. It is possible that the approaching rider has something good to say about the condemned man. That is why he is led back.

Now, remembering this Talmudic story the Rabbi told, we should cry out with the question: “Truly, this Rabbi and such dear Jews did not have anything to their credit?”

After the afternoon prayer, they arranged the traditional “three meals”. Actually, there was only a piece of hallah with some water on the table. However, this did not prevent Avraham-Ezra, the mason, together with Shepsl the carpenter, to sing in ecstasy Hassidic songs and start dancing with rapture, pulling the rest of the folks to a circle dance. Even the small children, the Moshe'lekh and the Shloyme'lekh, were drawn in, pulling at their fathers' and grandparents' hems to dance with them, all the while laughing and having fun in their childish naïve way. After havdole [ceremony when Sabbath is over], they danced to the hymn “Hamavdil” [the hymn after havdole:” He who makes a distinction between the holy and the every-day”], with the accompaniment of a violin and a drum like in happy times, unaware that the angel of death was standing among them, and in a short while there would be no memory of Jews ever existing there.

An exception was Shmini Atzeret [eighth day of Sukkot] at the hakofes [circular procession with the Torah scrolls around the reading platform]. That is when all the folks would gather - men, women and youngsters –in the market place and in the main street and proceed to Itzik's shtiebl to rejoice around the Torah. Issar the tailor, serving as a gabe [manager of affairs] used to stand on a chair to be able to see who was present in the shtiebl so as not to embarrass anyone by not giving him the scroll for a hakofe. He called out in a loud voice: “the bridegroom Yossef, son of R' Khayim Nissl is honored with a hakofe. The bridegroom Berl, son of R' Aharon David is honored with a hakofe”. Or, our yeshiva students were honored with the first hakofe. Even the small children were not excluded from calling them by the name of their grandfather; Yaakov, Shimon-Itzick's grandson, and Pessakh, Lieber's grandson and Avraham, Ezra's grandson adding the words: “because they knock over the shtiebl and break the window panes – they earn a hakofe.” All the while, Young and old, all together clapped their hands and united in a circle. The fathers and grandfathers rejoiced watching the young children, with flaming cheeks, carrying the scroll. The mothers and grandmothers were muttering “knock on wood” watching how their children were moving so gracefully and looking so handsome.

In the Besmedresh they prayed according to the Ashkenazi version and they already followed the customs of the Misnogdim [opponents of the Hassidim]. All the folks “from the street” Hassidim and Misnogdim came together to pray in the Besmedresh. And there, sitting by a long table, Alter, the blacksmith, used to teach the congregation Pirke-o'ves [“ethics of the Fathers”] in summer, and Ein Yaakov [a compilation of the legendary material in the Talmud with commentaries] in winter, talking about the good qualities a Jew should have and how a Jew should conduct himself. He explained that thanks to these qualities the Jews would never go under. As an example he brought Horodets: “Surrounded by so many gentiles, we have been living in Horodets hundreds of years and we will continue to exist until the coming of the Messiah, when all Jews will go to the Land of Israel.” He adorned his lesson with beautiful proverbs and phraseology, and the congregation was enchanted and the folks sat and watched Alter's permanent smile, white beard and clever eyes, expressing their great respect and reverence for Alter and believing in the wise words that he spoke.

At another table sat Alter the Levi, a Jew above 100 years old, still healthy and strong, teaching mishnayes in the Misnogdim's straightforward manner, and discussing in a scholarly way the dispute between the Tano'im [rabbis whose teachings in the first two centuries A.D. that are included in the Mishnah] and why did Rabbi held this one opinion while R' Natan held a different opinion, and this is how they spent their Sabbath and Holiday.

The Besmedresh was also the place to hold meetings. At the meetings all were equal, without a chairman. Everybody talked, made noise and all were equally interested in the issues discussed. The meetings were always about economic issues and the needs of the shtetl such as: fixing the fence around the cemetery that was getting worn-out to the point of breaking down, having enough water in the bathhouse, where to get enough wood to heat the bathhouse and the Besmedresh, or a fair distribution of the relief money that arrives before Passover from the American countrymen, not wronging anybody, etc.,

The shoykhet [ritual slaughterer] of the shtetl, Yoel, was still a young man. He was Zlatke's son-in-law. He was also a music player and served as a cantor during the High Holidays, or at a special festive event that took place in the Besmedresh. He was a quiet and nice young man, and when the old shoykhet Asher-David, 10 years before ww2 broke out, departed for the Land of Israel, he sold his right to Yoel. However, Yoel did not hold his job too long in Horodets because a short while after that, the Poles forbade ritual slaughtering. So he engaged a little bit in teaching and taught a few children. His kheyder was in the market place, in Brakha Kostrinsky's house. He did not have luck with being a melamed. The chief melamed in shtetl was Sender, son of Khayim-Sender's and the son-in-law of Mendel the mason. He called himself a “teacher”. Almost all the children in the shtetl were Sender's pupils. He considered himself a modern man and his conduct was modern. He wore modern clothes; always carried a cane in his hand, like a dandy, and in his other and he held a book. He boasted of being the teacher of the shtetl. Actually he was a very good melamed and the children loved him dearly, but they did not learn from him too much. The children had to learn in the Polish public school from nine in the morning to three in the afternoon.

There was a bathhouse attendant in our shtetl. In addition to being a bathhouse attendant he was also the undertaker and the caretaker of the cemetery. His job was to keep away the cows or swine that were grazing in the pasture next to the cemetery and were threatening to break in through the torn fence and, God forbid, damage the tombs and headstones. This attendant was Israel Moshe, the gravedigger's son-in-law who got the concession to be a bathhouse attendant and caretaker of the cemetery as a dowry. When Israel Moshe became old and later passed away, his son-in-law got the concession. His house was near the bathhouse close to the cemetery in the rear end of the shtetl.

Sender's kheyder, or as he called it: “school”, was in the besmedresh and consisted of 30 boys and girls. When a boy was talented and his father wanted him to study further, he would send him to Antepolye, because they had a big Talmetoyre [traditionally, a tuition free elementary school maintained by the community for the poorest children]. Over there, the children attended the Talmetoyre from early morning till evening, learning also Polish, Yiddish, khumesh [first 5 books of the Bible] and Gemore [Gemara, the part of Talmud that comments on the Mishna]. The melamdim in Antipolye were scholars and taught the children until they could study a page of Gemore independently. Many of the Horodetser children studied in Antepolye a whole week and would go home on foot for Sabbath. Sometimes they could get a ride with a Horodetser who would drive them to their homes, or with a coachman from Antipolye who would let them off at the station.

There were in the shtetl some modern and rich Jews who sent their children to Brest (Brisk) or to other towns to a “Tarbut” school. That was a Hebrew public school or high school. Great scholars did not emerge in Horodets under the Polish regime. However, all were good, honest, proud and conscientious youth. Still 4 yeshiva youth, the pride of Horodets, came out of Horodets who were quite big scholars. One of them, Kalman, Moshe Ber's son, Alter the blacksmith's grandson, was really a genius. Someone with such a scholarly mind can be found only once in several generations. In addition, he was very clever and handsome – indeed a prince. One year before the war, he married a wife who stemmed from the family of the Gaon R' Pessakh Rruskin, the head of the yeshiva of Kobryn. That was a sensation for us. His wife, Dina, was also a great scholar and a beauty.

The second yeshiva youth was my friend Barukh, son of Shimon Yaakov. He was a great diligent student. He labored and toiled a lot to be able to study and in the midst of night when all around was quiet and the shtetl and the yeshiva were all asleep, his voice could be heard in the yeshiva, studying the holy Torah. I remember that when we were quite young, studying in Antipolye or in Kobryn, it never happened that Barukh raised his eyes from the Gemore out of fear lest he would lose a word, and would not be able to interpret it on his own. He never had the time to eat and studied the text again and again with the purpose of not lagging behind.

|

|

|

|

Barukh Greblovsky

Yehoshua Ozornitzki |

|

Kalman Kupriyansky |

In addition he was very God fearing and pious young man and very virtuous. Barukh had a great talent for commerce. He was a great contractor and very industrious. Three years before WW2 broke out, he established a bakery in Pruzshane that prepared matzos not only for Pruzshane but also for Kobryn, Brest and Horodets and the whole surroundings. His matzos were famous all over Poland. A year later he got married in Visokey near Brest. His wife was the daughter of a big corn merchant and he opened there a matzo bakery doing great business. The third yeshiva youth was my cousin Yehoshua, Khayim Ozornitzky's son and Aharon-Itshe Leizer's grandson. He was a few years younger than me. He was also a great and diligent scholar and a good young man. He had a great talent for painting. In his free time when he stayed in Horodets, he painted and carved. When the war broke out he fled to Vilna – being then under the Lithuanian rule - with the purpose of immigrating to Shanghai with other yeshiva students.

When the Nazis, may their name be erased, set-up concentration camps, the Poles imitated them and set up concentration camps as well. Near Horodets, in Kartozbreze, they set up the most horrible concentration camp to which they sent, without any reason, Jewish and Russian youth who never returned alive. They did not even send back their corpses except for a small box with ashes for which they charged quite a lot.

The Russian population near us was in a very bad situation because the Russian farmer had to pay a third of his yield to the Polish land-owner. It was not permitted to have Russian schools. The Russian-Provoslav cloister that stood in the center of the market place of Horodets, was turned into a Polish Catholic cloister and this the Russian farmers could not forgive.

[Ben-Ezra, the editor, remarks as follows:

“For historic accuracy it must be admitted that the big white cloister in the market place belonged at one time to the Polish church and the small wooden cloister in the Pritzisher alley near the uriadnik [police constable], belonged to the Provoslavs. After the “miatezsh” in 1863 [Polish uprising], the Russian regime confiscated the big cloister for the Provoslavs and gave the small cloister to the Poles who lived then in Horodets and the surroundings].

The Russian youth, in their despair, became more left-winged and formed an organization aiming to bring about the secession of our region from Poland, to return it to Russia and thus be united again with their motherland. This activity entailed a death penalty. Many young farmers, from the shtetles and villages, were hanged. From our shtetl Horodets they also hanged in 1936 the leader of the Horodetser gentile youth, near the Kobryner jail. Another youth, Nikolai Tshinik, the feldsher's [old-time surgeon-barber] nephew, was shot [and not hanged], as a favor, because he had served in the Polish army. That was the type of Polish clemency… and as for the very young, they put them in jail. Through all this, the Horodetser Jews lived and hoped – the youth were striving to go to the Land of Israel, brave and proud. They often gathered to have good time together, and even sang and danced. They loved their shtetl, their houses and land. They married among themselves; children were born, increased and procreated. The children were raised on the street, walked always barefoot but were always happy. Every day they ran to the autobus that would stop on the highway near the market, and with clever-curiosity and naïveté scanned the faces of the arriving and departing people. They ran to the Tzigelner forest and even sometimes stealthily entered the Land-owner's forest near a big orchard, where they were caught red-handed... Among themselves the Jews were like a big family: invited each other to a wedding, or just to a small celebration. All participated in a funeral or a calamity. They named each other by their occupation: David the blacksmith, Shepsl the carpenter, Shami the quilt-maker, Naphtali the cobbler/shoemaker, Shlomo the shopkeeper, and Yoel the shoykhet, etc,. The youth and children were called in connection to their elders: Khashke Zlatke's, Motl Khana-Lea's, Yankl Khayim-Nisl's, David Shami's, etc. They did not call each other by their family-names.

The spiritual nourishment of the Horodetser Jews was the shtiebl and the besmedresh. The shtiebl was in the “market” [market place] and the besmedresh was in the “gas” [main street]. The shtiebl in the market place was built by Itzik the mason, in his own house, and paid for with his own money – sent to him by his children in America. Being alone, without legs, but wishing not to be isolated in his house, and also being a scholar and understanding what the shtiebl meant to him and for all the folks in the market place, he kept building, renovating, enlarging, improving and embellishing the shtiebl. Itzik alone decided how the work should be done, and as his regular carpenter he kept Shlomo Berger (in the shtetl they named him: Shlomo Lieber's – after his father-in-law).

The besmedresh was on the main street on the same grounds where the old besmedresh stood and was burnt down during WW1. It was rebuilt with the money donated by American countrymen.

I see you always, my Horodetser brothers, coming out to accompany me as I departed for America. I always remember your last words of goodbye hoping we would meet each other again. These words stab my heart. Now I write with blood and I say “Kadish” [mourner's prayer] over all of you.

“Yis-gadal v'yis-kadash sh'mai-rabo”!

|

|

“The Community”

Standing from right to left: Berl Liakhovitzky (Aharon-David's son) Motl Orlovsky (Moshe-Eliyahu's son) Yaakov Nadritzni (Acraham Ezra's son), Gershon Liakhovitzky (Aharon-David's son), Hershel Volinietz (Shmuel the carpenter's son), Shlomo Yarmetzky (Yaakov-Meir the cobber's son)

Sitting from right to left: Berl Rikhter (Liakhover), Shniska Blatzky (the eldest of the community) and Yaakov Bergman (Yaakov the mason)

[The two words on the roof of the house are in Polish: “community office”] |

[Pages 162-163]

Once there was

[A Lament]

By A. Varsha

Translated by Hannah Kadmon

[Translator's notes – in square brackets]

In my early youth, part of our big garden was supposed to become an orchard. A certain porets [gentile landowner] gave my father, the painter, a gift – 30 “stshepes” [a coin] rewarding him for my father's good and fine work in the porets' pokoy [estate]…

It was after the Holiday of Succoth. The garden beds lay faint, bare. Here and there some wild plants strove stubbornly to survive. The “titchkes” of the wrinkled string–beans shuddered in the cold and the yellow dry leaves, as if glued to the rod, were telling stories about a nice and blossoming day.

– “Tomorrow we will dig pits”, announced our father in the house, “the agronomist will come for measurements. Therefore, gather all the trash that is strewn in the garden”…

Something new was going on in the street. Neighbors were gathering, watching the agronomist's every step and marveling at the tricks of measuring. Two gentiles in blue garments dug pits and threw in, one after the other, spades full of yellow gravel.

“Hey, people!”, one of the diggers shouted: “galava!” (a head!). Everybody rushed to the pit with bewilderment. I started shivering from the cold despite the warmth of the noon–time sun.