|

|

|

[Page 102]

by Duvid Zahavi

Translated by Elizabeth Kessin Berman

In our town, Radzivilov, as in many Volhynia towns, many diverse Zionist associations were organized after World War I. But before that, there were other clubs whose role was to influence our families' young people. Already from the earliest days of our childhood, the our students' education in the government elementary school offered us a Hebrew Zionist education, and the Hebrew teacher, Hershel Katz, taught us and indoctrinated us. I recall that already during those days, there was a young Radzivilov man, Mendil (Menachem) Goldgart, a cousin, who left his respectable and wealthy parents' house and journeyed to the Land of Israel. We, the younger children, were then very much in favor of this. But not his parents. It wasn't easy for Mendil in the Land of Israel, because he'd had no experience of physical labor and, furthermore, in those days it wasn't easy for a Hebrew laborer to get work. But this did not alter his strong resolve, and he soon overcame the difficulties. After a number of years had passed, he came to visit Radzivilov, full of enthusiasm, and he began to enchant the young people with the tenets of Zionism. He finally convinced his father to advance him an amount of money in order to return to the Land of Israel to build a factory, not at all large, as a trial. But then World War I broke out.

As the military drew near, we, like others caught in the middle, fled from Radzivilov to Berdichev. There our parents continued in their business, and we children entered the gymnasium and continued to study. We dedicated all of our time to working for Zionist youth clubs. Youth in Russia were fired up by what Zev Jabotinsky was writing in his fiery articles. His articles were popular even among the gentiles.

When the revolution broke out in February 1917, and the Bolshevik revolution afterward, a number of things changed for us. I was the first in my family to cross the border into Poland, and I went to relatives in Lutsk. There in Poland, the Zionist movement was little by little gaining more appeal, and many more were becoming interested in immigrating to the Land of Israel. Then, in Grokhov, near Warsaw, there was a Pioneer training center, where a group of 10 girls and boys worked in agriculture to receive career training prior to immigrating. I participated with them.

[Page 103]

When my parents returned from Russia, I also returned to Radzivilov, and until I got my certificate, I devoted myself to work in the Youth Guard organization as a leader of the local “nest.” Jewish youth began growing in stature, but the anti–Semites also raised their heads.

|

|

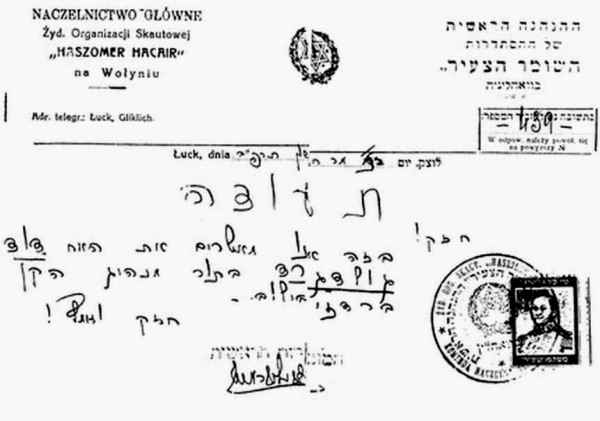

| The certificate reads, “Main Office, Jewish Scout Organization, Youth Guard of Volhynia, Lutsk, #439, 7 Heshvan 1922. Certificate. Congratulations! In this we certify this person, Duvid Goldgart, according to the nest's custom, in Radzivilov. Be strong and of good courage!” |

|

|

| Young Lions of the Youth Guard, 1922 |

[Page 104]

I remember one incident. It was on a Sabbath afternoon. A few Youth Guard platoons went out to check an announcement for a Zionist event that was supposed to take place on Saturday night. When the young people began to examine the announcement, a group of “settlers,” Polish guard soldiers whom we knew were anti–Semitic killers, suddenly appeared and began to tear up the announcement. We shouted for the older members, the Liberman and Goldgart sons, who happened to be nearby. They appeared, and when they spoke roughly to the Polish rioters, one of the Poles snapped the whip that Shlome Liberman was holding. A fistfight broke out on both sides when Rivke Liberman, who didn't leave us a minute to spare, made booing sounds in the Poles' ears. Gradually more Poles appeared. We told ourselves to scatter, because we were worried about our relations with the Polish government, but they didn't back off. Shalom Goldgart, the youngest and smallest of his brothers, fell on one of the Polish brutes with raging fury, punching him, and the fight continued between them. But with difficulty, we came to an impasse, and then we quickly scattered.

But this incident raised awareness of the local youth in the eyes of both the gentiles and the authorities.

|

|

| Youth Guard Graduates, 1922, Led by Duvid Zahavi |

[Page 105]

Because of this, the next day the government authorities met with the Jews and the “settlers,” and the storm abated.

After a number of years, I finally received my certificate to immigrate to the Land of Israel.

|

|

| Young Lioness, Youth Guard |

by Moshe Korin

Translated by Elizabeth Kessin Berman

Three years after the establishment of Polish rule in Volhynia, many Jewish residents of Radzivilov returned from the places to which they had scattered during World War I. At the same time, Zionist movements began working in earnest to organize Jewish young people, and Pioneer set out to train everyone who requested to leave the Diaspora and immigrate to the Land of Israel to take advantage of the conditions created when the British Mandate came into being in the Land of Israel.

Delegates from central Pioneer were sent to our town, and with their aid and advice, a local young workers' branch was organized in Radzivilov.

[Page 106]

In 1923, the branch also acquired its own facility, even though it was an abandoned house recently vacated by the Zaks family, but there young people aged 17 and above engaged in listening to lectures on the movement, its teachings, and its political parties and their ideologies, and they discussed and planned their dreams of immigrating to the Land of Israel and the new life they would establish and advance there.

We mention here the first trainees to be ready to immigrate: Niuni Goldgart, Sabe Zaks Pontis, Kitayksher, Lindiner, Sirota, Yoel Cherp, Simche Ayzen, Tsipore Gun, Ester Blekhman, and others. Working in cultural and social areas was Moshe Taykh, the oldest in the group, who it seems to me made great strides in establishing the local Pioneer chapter.

|

|

Seated: Munye Margaliyot, Buntsye Vinshteyn, Dvore Taykh, Arye Vaynshteyn. Below: Akiva Vaserman, Teme Shif, Meir Vaynshteyn |

The first trainees left to work in 1923. The members of the first training group to be part of the agricultural collective were Beti Benderski, Eychis, Reshish, Berdichevski, and others.

[Page 107]

The first group, which wrote one of the columns, left for the Radzivilov–Druzhkopol training kibbutz near Lemberg, whose members worked in three large sections. These included Jews from the following villages: Michalow, Zvuche, and Volitsa Barylova. The kibbutz mentioned above had more than 150 boys and girls from all over Poland.

After working for four months in the summer, many gladly immigrated to the Land of Israel. And almost everyone from our town was able to acquire a certificate and immigrate, except for a few who remained for various reasons.

After the first group had immigrated (individuals had already immigrated on their own), the Pioneer branch rapidly developed, and many other cooperatives began the process of training and immigration. Among the Pioneer activists until the 1930s were Yakov Lerner and Avraham Vaysberg. Yakov Lerner suddenly left the movement, and in the 1930s, there was also a crisis among the Pioneer leadership, and the movement almost dissolved. Buntsye and the Vaynshteyn brothers, as well as Yehoshue Felman, did everything they could to keep the movement intact, and Young Pioneer, which was organized in our town in the following years, came and strengthened its roots. Among the Young Pioneer members during the 1930s, I must mention B. Felman, Yosef Lerner, Duvid Vaynshteyn, Yakov Segal, Mordekhay Landis, Yosef Sigen, Yisrael Nudel, Avraham Korin, and others.

|

|

| Celebration in Honor of Radzivilov Trainees Who Were Certified to Immigrate |

[Page 108]

Yisrael Nudel did not get permission to immigrate, and it appears that he was a victim of the Holocaust that gripped our town.

All these activitists that I have recalled above and, yes, many more after them, had years of training in different kibbutzim all over Poland. These were the days of great growth in of the youth pioneering movement, with branches and training kibbutzim in broad regions of Poland, but in terms of immigration, the results were almost insignificant. Many thousands of pioneers in training kibbutzim looked forward to immigration, and in our town, too, a substantially large training kibbutz was founded mainly to work in our town's flourmill, and the Jewish owners helped us operate it and establish a local cooperative. The cooperative itself served as a spiritual and cultural resource for the local branch.

|

|

| Pioneers before Immigrating to the Land |

And so it was that, in spite of the occasional crisis that befell the local Pioneer branch, they remained steady in their work until World War II broke out in September 1939. On the 17th, our town came under Soviet control, and then all Zionist operations halted, which thus confirmed the complete demise of the Radzivilov Pioneer branch.

by Meir Vaynshteyn

Translated by Elizabeth Kessin Berman

With the end of World War I, many of the residents who had taken flight to different regions of Russia during the war returned to our town. Many of the returnees were enlightened individuals, sensing the need to organize young people and to teach them how to prepare for immigration to the Land of Israel. Among the first initiators and organizers, who are remembered fondly, were comrades Shimon Goldgart, Yozik Zaks, and Shlome Libov.

These were days of national awakening, and the Pioneer movement in Poland was developing and taking hold. The objective was to try to immigrate to the Land of Israel. The abovementioned organizers unified many of the area's young people, made a connection to central Pioneer, and then established a local branch of Pioneer there. In the evenings and on the Sabbath, discussions and lectures were planned on the new life that was evolving and taking hold in the Land of Israel, life on the collective farm and commune, Zionism, and pioneering, The ideas that came like burning and raging flames to the young people aroused in them aspirations to immigrate. The realization of these ideas was a life of labor in the Land of Israel.

It wasn't long before a group of young people from our town began to go to the training kibbutzim organized by central Pioneer; and the Land–of–Israel spirit that enveloped our town gave them the impetus to learn Hebrew in evening classes, as well as to establish the Tarbut School. In the evening, we also occupied ourselves singing Hebrew folk songs, and this spirit so filled our parents' houses that they also received inspiration from the vision that new lives were rising from the dust in our Land of Israel. They began to realize how depressing it was for us to live in the Diaspora, how cruel the surroundings of our anti–Semitic town were, and in comparison with Zionism, how beautiful the dream of a new day in the future was for Jewish youth in the land of their fathers.

The Pioneer concept conquered all of us, and each day new members joined us and stopped pining for their home to join a life of training in preparation for immigrating to the Land of Israel. These were joyful days for us, for encouragement in an almost Land–of–Israel environment, and for the urge to be creative and organized. Zionist institutions and parties were founded and organized, as well as branches of Pioneer and Young Pioneer in our town. A local training “kibbutz” was also established, and pioneers from several cities came to us for training. Correspondingly, many from our town went for training in Grokhov, near Warsaw; to Klosova; and to other points. The training program in our town centered on the flourmill, a monastery, the railroad station–in dismantled cars–and especially on chopping wood for the Jews of our town. It wasn't demeaning work for them–on the contrary, they asked for hard and menial labor in order to get used to and prepare for physical labor in the Land of Israel.

[Page 110

Life in the training programs followed a communal, cooperative structure, and for many, the wages were most meager and the level of living very modest. Nevertheless, everyone greeted this difficult life with love, and the great reward was this–a certificate for immigration.

It should be pointed out that the Polish government did not restrict our progress, and the Pioneer organization acquired official government recognition all over Poland. The Pioneer branch in our town also acquired, certainly, legal status. And here I recall a delicate situation that happened to me one day. A Polish policeman came to collect information from me on our organization and its officers. He knew me in connection with various issues, and although I knew that the policeman was clearly an ardent anti–Semite, he related to me with great respect and tried to explain to me that even if I immigrated to the land of Israel, there would be a chance to return as a Polish citizen–if a war broke out–and fight here (in Poland) for the Polish homeland. I answered him immediately with the pride of a Jewish nationalist.

Our house was a haven for all Pioneer activities. It was open to everyone, and everyone who passed by felt an emotional need to enter, enjoy the camaraderie, and spend time in a pioneering Land–of–Israel atmosphere. On Sabbath eve and also on the Sabbath day, Pioneer and Young Pioneer members would gather in our house for discussion, a game of chess, sing–a–longs, and lectures on civic and Land of Israel subjects.

On Sabbath eve, our large table would be spread in the best Jewish tradition: covered with an immaculate tablecloth on which stood candlesticks with burning candles in them Everyone sat around the table with a good feeling of “sitting all together like brothers,” singing hymns, Hasidic melodies, and songs of the Land of Israel that blended youthful dreams and aspirations. These were gatherings in a pleasant house to honor all of us, and even though we were removed from reality, in spirit we were still in the land of our fathers.

Neighbors, both Jewish and non–Jewish, knew that our house was filled with pioneers who were planning to immigrate to the Land of Israel. No one bothered us when we sang, sometimes by moonlight, even after the candles and streetlights had gone out. The policemen related to us with respect, and sometimes they even asked us to lower our voices so as to not disturb the serenity of the night.

With the rapid passing of years, 10 boys and girls immigrated to the Land of Israel, and they were accompanied to the train station by many of the town's Jews.

by Arye Ayzen

Translated by Elizabeth Kessin Berman

Radzivilov was a border city between Russia and Galicia, approximately nine kilometers from the well–known city, Brody.

This was a town like all towns in Volhynia, with Zionist organizations such as Pioneer, Youth Guard, Gordonia, Betar, General Zionism, and more. And then there were the philanthropic organizations, such as the poorhouse, the old–age home, the welcome committee, the committee for orphans, and more. It is important for me to call to memory at least a few of the people who worked, led, and prepared our town's young people in the spirit of Zionism with great personal talent.

Here are some of the leaders of the Zionist movement that were then in our town.

Chayim Kerman. They were already calling him the most enthusiastic Zionist in the days when many of our young people did not even understand what Zionism was. Enthusiastic, especially with those from religious groups who were opposed to it, who urged that we wait for a god who would surely come … he would lecture at Zionist gatherings in our town, and his descriptions would illustrate life in the Land of Israel and how to build it, as if he were there building it. He was so accurate that many of his students could picture their own path and the work he was dreaming of.

Dudke Sheyn. He was at his best and strongest when educating and nurturing our Zionist youth. His life was already in the Land of Israel. No one could convince him otherwise–until his final departure from our town. He also created a memorial book for the community of Radzivilov and its martyrs. But their death did not prevent him from putting theory into practice.

The Zagoroder family. Everyone knew the first Zionist family in our town. R' Menashe Zagoroder's house was an open house offering hospitality to officials from the Land of Israel and the delegates from the central Zionists in Warsaw, the largest and first Zionist organizations: the Jewish National Fund and United Israel Appeal. He would also appear at lectures, disseminating the concept of returning to Zion to the Jews of Radzivilov. He was also a representative to all the Yiddish and Hebrew newspapers in Poland and abroad. Totally devoted in heart and soul to Zionism, he educated his sons in the spirit of Zionism, and all of them immigrated to the Land of Israel.

His son, Tsvi Zagoroder, is to this very day a Zionist loyalist and leader of the descendants of Radzivilov in Israel.

[Page 112]

He took upon himself the huge work of publishing this memorial book for the community of Radzivilov without losing any of the many connections he came upon.

Dudke Goldgart–Zahavi. I remember him as a leader and guide, the best of our pioneering youth. He was able to arouse in Zionist youth a sense of communalism and the desire to immigrate and lend a hand in building the Land of Israel.

|

|

| The Hertseliya Group Led by Tsvi Goldgart, 1925 |

To the best of my memory, these were the Zionist families who worked as leaders and heads of the Zionist institutions in our town:

Zagoroder, Goldgart (Moshe), Balaban, Korin, Tesler, Lerner, Gelman, Goldgart (Beyrish), Soybel, Zaks, Shumker, Kitayksher, Sigen, Kiperman, Kerman, Vaynshteyn, Grubshteyn (Sley), Margolit, Felman, Margolit, Sirota, Mikhel, Vayl, Chait, Stroyman, Grubshteyn (Yechiel–Duvid), Zats, Daniuk, Poltorak, Landis, Fishman.

by Yosef Spektor

Translated by Elizabeth Kessin Berman

I was 16 when I joined Pioneer in Radzivilov. My parents, who were very traditional, didn't approve of the Pioneers' work in the training center. They weren't used to seeing Jews doing the kind of work the gentiles did: chopping wood, sawing wood, doing the lowly work of the flourmill, and so on. They tried to convince me to give it up, but instead I decided to stand fast and continue on the path I had chosen and to fulfill the great dream of living as a Jew in the land of his ancestors.

In 1936 I went to the Borokhov training kibbutz near Lodz. After training for more than two years, I was certified for immigration to the Land of Israel. I returned home to prepare for immigration. My parents didn't object to my immigrating to the Land of Israel, and my mother even wanted to equip me with all sorts of expensive items, although my family members weren't aware that I was immigrating in the second wave and there was no way to take anything with us but the most necessary things. Because of this, I didn't even take family photographs with me, and now I can only imagine them, the dear souls, as I have them fixed in my memory…

When my relatives came to bid me farewell, my father said he was comforted that his son was immigrating to the Land of Israel because he would live there as a Jew among Jews. During the last moments before my departure, he cried and said, “Who knows if I'll ever see you again, my son?” He didn't, not him or the rest of the family, who were torn from life at the Nazi murderers' hands.

by Tsvi Zagoroder

Translated by Elizabeth Kessin Berman

|

|

| Yafe Broida |

Yafe Broida, daughter of R' Yehoshue Broida, of blessed memory, was among the first in Radzivilov to immigrate. She arrived in the Land of Israel in 1923 and entered the Immigrant House in Tel Aviv.

Roadways and Malaria

The Immigrant House in 1923 was nothing but a camp of tents set up in the middle of Tel Aviv, not far from the Robert Samuel Port of today. A huge wave of unemployment was then gripping the country. For three days, Yafe Broida rested in her tent doing nothing, along with an elderly Jewish woman who had come to the Land of Israel to die there. On the fourth day, she packed her belongings and left to search for work. She approached Avraham Hertsfeld, head of the agricultural agency, who was very sympathetic to youth from Poland, and explained to him in a decisive tone that “she had come to the Land of Israel to work, with God's help”–”the land calls to me; give me something to do.” The head of the agricultural agency took her words seriously, and as a result, over the next 10 years Yafe Broida did the following: she packed tobacco near Kfar Tabor; hauled goods and laid bricks with a team of workgroups near Kfar Yehezkel; laundered sheets at the Ein Harod hospital; participated in building Balfouria; paved the Afula road; caught malaria; and recovered, picked up an ax, and took part in the excavating the repair of drainage pipes for the Jezreel Valley.

[Page 115]

In spite of the opposition of Dr. Krauze, manager of the agricultural school in Mikve Israel, to the excavation, she was the only girl to take a course on nursery plant growing intended only for boys; because she now found herself near Tel Aviv, she helped pave part of King George Street; she joined a team of road levelers and was a daily worker in the Kfar Saba orchards; during the day, she staked the trees and in the evenings, she utilized the course in nursery planting to establish the first nursery, giving Kibbutz Givat Haim a level surface for their current orchard; she left the country for two years as a movement delegate to the Volhynia region, the place of her birth, and worked in Pioneer Kibbutz training centers; she returned to the Givat Haim orchards and began to work at sorting and wrapping. The “packaging guild,” which opposed allowing a woman in the packing industry, found a worthy fighter in Yafe Broida; she learned the trade from a Givat Haim member in secret. The results of this were welcomed by many other members, and the trade was considered to have been conquered by the “weaker sex.”

Left the Kibbutz because of the Tractor

With the outbreak of the world war, life changed in Givat Haim because the weight of the economy fell on the women as the men left for the front. Yafe decided to take part in an accelerated course called “regional tractors.” The members tried to dissuade Yafe, because how could she operate in a trade that was so masculine? When she returned from the course, the men grumbled and expressed their hostile opposition. But even so, they were compelled to accept her into the work, although it would not be tolerated for long. As Yafe recalled, “My life had no meaning. They talked behind my back, said that I broke parts, that I had impaired vision, and other slurs. This was unjust, but I had the feeling that it was only up to me to disprove to them and to myself …”

When she realized that her hopes to join the Givat Haim tractor division of were shattered beyond repair, she left the workforce. For two and a half years, she was the secretary of a labor group in Ramat Gan. But her heart still beat for the earth and the tractor. When she finally met with the manager of the kibbutz, she asked if she could return to the workforce on fair terms and to take on a task that would not upset the male kibbutz members. The manager was very sympathetic, but he could not promise this. “I saw only one way before me: to take it upon myself to achieve my goal. I took 25 liras that I had received from my last salary and went to the Israeli ministry of civil tractors and equipment.”

[Page 116]

This was the first official payment for receipt of a tractor tendered by a girl. The manager told Yafe that 173 people, all men, were waiting, listed her as a girl, told her he didn't know how long it would take, and so on…

Yafe's Turn Comes

Yafe became a cleaning woman and resigned herself to waiting. Five years later, the State of Israel was established, and she was finally rewarded. “Miss Broida,” said the association official, “you can receive your tractor–but you must bring permission from the Ministry of Agriculture.” In the Ministry of Agriculture, the clerks looked at her and laughed: “You have no prospects. The Ministry of Agriculture cancels the mechanical appointment and imposes a better method. You can fill out this form …” The answer was negative.

|

[Page 117]

Yafe wrote to an old acquaintance, Chayim Halperin, then manager of the Ministry of Agriculture, and told him of her struggles.

At the beginning of 1951, she received the long–awaited permission, and immediately afterward, she gathered a group of kibbutz members and older members in an effort to amass 1,800 lira–the amount needed to order a 4D–type “Caterpillar” from the association's warehouse. But there still was no respect for her.

There they asked her, “Who will operate the tractor, your husband?” “They recognized me well, they were polite, but they declined to allow me to come and go, they did not give me any work. I was a woman, and if I did this work–in their opinion–it might rattle every sector in the whole country.”

The Arabs Were Not Surprised

Yafe Broida was stunned by the old–fashioned conservatism among the Hebrew farmers, while the Arabs couldn't have cared less who was driving the tractor. The idea arose to approach the Arabs and, indeed, she got her first work from them. The Arab guard of Ein Shemer returned to his village, Baqa, one day and told Knesset member Faras Hamdan of the signs and wonders of the woman with the tractor. For long weeks, she plowed triangulated borders until a letter arrived one day inviting her to come to the Negev to work on a deep plowing project. Yafe Broida plowed on for two straight months the land of Ein Iron, which was wild with infiltrators. They would appear very frequently, coming down from the hills and stopping to hear the noise of the lonely tractor… And Yafe was not one to let her guard down. But although there were frequent encounters, sometimes face to face, with those who were crossing the borders unseen, she did not fire even one bullet. She had a certain philosophy, and she literally used agriculture to express what was close to her heart: you should not let the Arabs who are close to you know that you fear them–because then they will become as quiet as water and as small as the chaff of the field.

A House on Wheels

Ever since her victory at the end of 1951, she could not tear herself away from conflicts. She still believed that she could join the tractor drivers' union. The wounds of the past had not yet healed. But agriculture would not suffer because of Yafe's determined independence. She set out to plow in the Negev, regions always far from the connections and opinions of the tractor drivers in the northern parts of the country.

[Page 118]

|

|

| Yafe Broida Tends Her Tractor |

On her own, Yafe “conquered” thousands of dunams and many tens of kilometers, in which the Jewish National Fund sowed fields and planted trees–all in the Negev and along the Gaza strip.

When the American specialist who worked on the survey was about to return to his country, he left her the portable “trailer” that was used as a housing unit. And so she hauled it with her wherever she was sent and lived in it until she finished her work. Afterward, the “house on wheels” was turned into a small storage facility for field equipment, something she was very proud of, and when she went out on new jobs, Yafe would equip it with enough vegetarian food for a month, and two tanks of water, using it as a mobile workshop trailing after her–everything in her world with her. She was full and complete. “How long, in your opinion, can you go on like this?”

[Page 119]

“At my age (51), there are only single men in this industry to compare to. But I'm a woman, and it is hard to know.”

In 1955, Yafe received an award at the Ministry of Labor celebration held in Beit Lessin for high performance and for her independent tractor service. Among those in the audience were Institute of Productivity and Industry and Labor Ministry officials, including Labor Minister Golda Meir.

To our questions about how many more years she thinks she will continue in this line of work, Yafe answers that she doesn't think about that at all. She will work until the last day… We, the people of Radzivilov, wish her, a daughter of our city, a very long life.

|

|

| M. Grinberg, Son of Our City, from Richmond in the United States, Founder of Nahala in Israel. |

Footnote

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Radyvyliv, Ukraine

Radyvyliv, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 21 Apr 2015 by JH