|

|

[Page 397]

The Last of the Eglonim (Coachmen)

Elazar Prashker – Jerusalem

“Three old-time coachmen can still be seen on the streets of Rishon Le Zion”

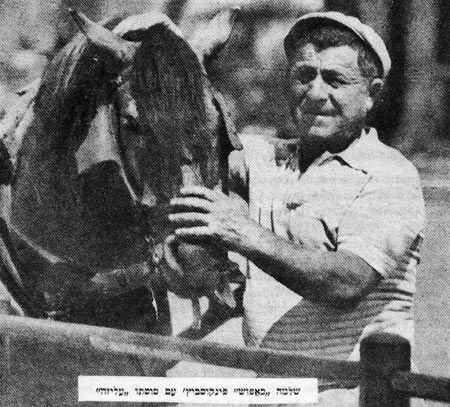

I happened to glance at the above quotation under a picture in an article describing a vanished world. The article in question appeared in Kol Rishon Le Zion in 1983. One of the “old-world characters” in the picture was Shlomo (Hapush) Pinkusewicz with his horse, Aliza.

As you who lived in Piotrkow have, no doubt, guessed by now, the image shows none other than our own townsman of the well-known Hapuchis tribe, who inherited the profession from his father and grandfather. All of us remember Shlomo perched atop his wagon in the fashion of his father, Hershel Hapush, and his grandfather, Wolf Hapush. Shlomo immigrated to Israel in the 1950's and has since then carried on his honorable profession on the highways and byways of Rishon.

Seeing the article in Kol Rishon Le Zion reminded me of an old picture published by The New Piotrkow Bulletin of Sept.-Oct. 1982. In that photograph, a fine group of old-time coachmen – the droshka drivers we all so well remember – assume a formal pose for the camera. The photograph had been sent to The Bulletin by Jack Bulwa of California, who himself was the son of a droshka driver; his father is pictured in the group. Ben Giladi, editor of The Bulletin, added a sorrowful sentence to accompany the picture: “A scene from what was and is no more.” How right you were, Ben, my friend. This is indeed a world that has vanished, a tragic void and loss for which we will never cease mourning. The sudden and brutal cruelty of our tragedy is an everlasting pain in the lives of those of us who survived.

It is important for us survivors to hold onto memories, not only in order to soothe our sorrow, but also for a sense of roots and belonging. I find myself looking at this “graduation picture” of the droshka drivers and suddenly I am transported back to a childhood of which these colorful figures were an inseparable part. Although Jack Bulwa didn't mention who took the picture or when it was taken, I can assume almost with certainty that it must have been taken at the studio of Ben Zion Kogan, originally located on Narutowicza Street and later on the Avenue of the Third of May. My guess is based on studying the fashions worn in the photo as well as on the quality of the photography. As I study this photograph, I am most impressed by the well-pressed and elegant holiday attire worn on this important occasion by the hardy crew that is pictured. These folks were hardly ever seen out of their work clothes. Their attire speaks of a sense of self-respect and declares, “This is what we were really like!” – and, truly, they were.

|

|

| Shlomo “Hapush” Pinkusewicz with his horse Aliza on the streets of Rishon Le Zion in 1983 |

The society of these coachmen indeed formed a closed social circle within the Jewish world of Piotrkow. The profession stayed within certain families and was passed on from father to son.

Although the somewhat snobbish society of middle-class Jews may have looked down on these fellows, the “droshkazes” took pride in their work and simply ignored the opinion of elitist society.

It is certainly true that the coachmen were a rough crew, permeated as they were by the perfumes of horseflesh and leather. They were, however, never rude or vulgar. They were certain of their appointed place in the scheme of things and they also knew how to show as well as how to command respect.

The coachmen socialized mostly among themselves. Each of their families had a special coded nickname. In town they were known mostly by these. They were as proud of these code names as any nobleman might be of his crest and title. Few people in town knew their original family names. They lived mostly in Wielka Wies and Chazir Market. Their wagons took up position in the Chazir Market and on the Platz Zamkowy, while their carriages waited for customers at the railroad station and in Piotrkow's central spot, Rynek Trybunalski. On workdays, and only then, the carriages were parked along one side of Rynek Trybunalski, patiently waiting for customers.

|

|

Here are the coachmen of Piotrkow (dorozkarze). Top row standing, left to right: Moishe Szwarc, Itzik Sandowski, Itzik Kepele, Yosel Mishkitz, Chuno “Mizelik” Belzacki, Jack's father Bulwa, and Chuno “Bendlmacher” Gutman Sitting, bottom row, left to right: Michuel “Mencennik” Huberman, Hershel “Bendlmacher” Gutman, David “Sheygec” Fisz, Meyer Rozpszer, and Yosel Pitzer The “droshkes” played an important role in the dreams of our youthful minds. It was a big thrill for us kids to hitch a ride or, better yet, to be given the “leitzn” and be able tolead the horse. Let's stop for a moment and ponder when looking at this photo of these strong, honest men. A photo which is only an image of the past and nothing more ... |

Behind the droshkas, I can still quite clearly see in my mind's eye, the row of shops – Grabowskis's pharmacy, Tennenbaum's pub, Rabbi Schlomo Fuch's leather goods store, Weishoff's shoe shop, Shmaragd's paint store. I see the tired horses doze with their heads down, while the drivers, in their uniforms with shiny brass buttons and special peaked caps, rest peacefully atop their elevated seats. The restful pose does not prevent their ever-watchful eyes from keeping a lookout for the approaching “kurs,” and when such a potential passenger appears, every slumbering muscle springs into action. Whips flick, ears perk up, and the horses step impatiently in their place as if they were the horses of shining knights readying themselves for a joust. Like arrows from a bow, the carriages fly out to “catch the `kurs.' “ First come, first served!

Making a living was never easy. The coachmen worked hard from dawn to dusk, in the heat of summer as well as in the snow and sleet of winter. Each day had its own uncompromising workload. The horses had to be fed and tended. The carriages and wagons had to be repaired and made presentable. But on the Sabbath and on holidays, the coachmen would dress in their very finest and promenade at their ease to the synagogue.

I grew up in the house of Berl Scenick Zygmuntowicz, my grandfather; it was located in the vicinity of Wielka Wies, close to the quarters of the coachmen. From early childhood I learned to like and respect them and their trade. In the old photograph, I recognize Yosef Moskowitz of the Myshkis family. He and his brother Moshe, together with their parents and an unmarried sister, were our neighbors. Their large yard had enough room for their entire business inventory, both animate and inanimate. There was a stable for the horses and a shelter for the carriages and sleds. And a wooden shed for storage of discarded harnesses, wheels and other lovely junk—what a heavenly playground for us kids!

My younger brother Hershelle (known as “the mazik-menace”) and I had the yard all to ourselves. We explored every nook and cranny of it. We “helped” the wagoners to repair carriages and take care of the horses. We also learned how to turn the hay cutter. This was indeed our favorite game.

Surely such small rascals must have disturbed these rough-and-ready fellows in their work; they certainly had to keep an eye out for any mischief we might get into. But the bachelor brothers treated us gently and patiently. Never once do I recall them scolding us. As a reward for our “help,” they allowed us to sit next to them on the drivers' seats and hold onto the reins and whip as they drove out past the large gate on their way to another day's toil.

Winter, with its snowfalls, provided our greatest pleasures. This was the time for sleds to emerge. We were permitted to glide on the snow, accompanied by the jolly sound of the jingle bells which had been attached to the harness.

Here in the old photograph I also recognize the full figure of Michael Mentzenik. Is there anyone from our town who still recalls that this fellow's real family name was actually Huberman? Michael owned a gigantic lumber wagon and a heavy Belgian work horse with an impressive posterior. Man, horse and wagon appeared eminently well suited to each other. When Michael took his place on the driver's seat, his own immense shape filled two places and competed with the girth of his horse.

My father used to tell the story of a coachman who seemed to have taken out a lease on transporting the young brides of our town to the wedding hall on the day of their nuptials. If ever the unfortunate bride dared to be a few seconds late for the occasion, the whole street would reverberate with the voice of the wagoner: “Pisherin, vi lang velech varten oyf dir?” (“You little squirt of a bride! How long do you expect me to hang around waiting for you?”)

My memory fails me. Was Michael Mentzenik the hero of my father's story or was it someone else? After all, I was only a youngster when I first heard my father tell this story. Many years have gone by and, when I heard it, I never dreamed that one day I would want to write about it. Still, the description of the shouting wagoner does seem to fit the heavy-set Michael perfectly.

In the center of the old photograph sits a fellow who appears to own the world- David Fish, alias David Sheigitz, the P.R. person for the wagoners. In Yiddish, David was known as a “gantzer Kochlefl.” Because education was not exactly the strong point of this crew and because they were neither great scholars nor strong on rhetoric, David Sheigitz was useful to them. He possessed both temerity and charisma. He could think on his feet and knew how to get things done. David was a frequent guest in our. yard because some of his relatives lived at my grandfather's. I clearly remember one of the family, a wizened, cheerful tailor, Meir'l Schneider, and his wife, a large, clumsy and confused woman who went by the strange nickname of “Meir, Meir-Copenhagen.” I doubt that anyone knew her real name.

David usually was cheerful. He joked with us children, told funny stories, chatted with my grandfather and my uncles, and whispered business secrets to Moshe and Yosef. As a rule, he had something pleasant to say to everyone. That's why the story I am about to tell surprised us.

It happened about ten years later, just as our community was in the throes of a rabbinical election. After the death of Rabbi David Temkin, Piotrkow was without a rabbi for a whole year. Rabbi Yankele Dayan was temporarily in charge of synagogue business. No Jewish community can last long without a rabbi, and eventually the town elders decided that our community would have to elect a new rabbi. The Piotrkow rabbinate was considered a serious position. The town was known for its Talmud scholarship, as well as for its successful business activity. We had been blessed with “gaonim” and learned Torah scholars. Small wonder, then, that some of Poland's mosts promising rabbinical talents competed for the job. The position in the past had been held by such luminaries as “Brit Avraham,” “Nefesh Chaya” and “Ora V'Simcha.”

One of the contenders for the position was Rabbi Schmuel Brott, the leader of “Mizrachi.” He was later elected rabbi of Tomashow, our neighboring town, and later on became a rabbi in Antwerp.

Agudat Israel, as well as most “Chassidim,” including the “Gur Chassidim” in our town were backing Rabbi Meir Shapira, an upcoming star among the ultra-orthodox. Young as he was, Rabbi Shapira had already been one of the leaders of Agudat Israel and the representative of this group at the Polish “Sejm” (parliament).

The “Chassidim” of Sochachew preferred their own leader – the Admor Rabbi David Bornstein. Yankele Dayan was also a candidate. He was strongly supported by the Alexander Chassidim and by the men in the street. Needless to say, the Gur Chassidim were the most influential. In 1924, all Jewish males of age voted for a rabbi. Women, or course, did not vote – what does a woman know about selecting a rabbi?! Electing a rabbi was no simple matter. As a matter of fact, it turned into a serious struggle. There were assemblies and there was burning eloquence. The Aguda brought in Itzik Ber Ackerman, editor of the Warsaw Aguda newspaper, Der Yid. Ackerman was invited in order to help organize the campaign of Rabbi Shapira. Does anyone still recall Avremelle Leventhal? He caused quite a stir by marrying Baruch Cimbler's daughter. Baruch was a well-known horse trader. During the elections for Rabbi of Piotrkow, Avremelle served as chief P.R. man for Rav Yankele Dayan. He appeared at all the rallies and spoke with intense enthusiasm. People went to election rallies the way one goes to the theater. It was amusing to hear the fiery debates between Avremelle and Itzik Ber Ackerman. In short, everyone enjoyed himself!

Rabbi Shapira's personality captured the heart of my father, who soon became one of his most avid followers. My father joined the Shapira forces and the “election headquarters” run by Itzik Ber Ackerman found their way to our house. By this time we were no longer living at my grandfather's, but on Pilsudski Street, opposite the prison.

At this time Yerubal, in Unzer Zeitung, published a parody which poked fun at the entire campaign and especially its chief protagonists. Among those singled out for special ridicule were my father and Ber Ackerman.

(I quote from by best recollection as unfortunately I have not been able to lay my hands on the relevant copy of Unzer Zeitung. Sixty years have gone by, yet I still clearly recall the black-bearded Itzik Ber Ackerman. In my mind's eye I see his fiery, penetrating eyes. I see him dressed – not as was the custom among the Chassidim – in a short jacket and soft hat. I see him chain-smoking and incessantly drinking strong tea. His glass had to be constantly refilled up to the brim like a wine glass for “kiddush.”)

Ber Ackerman sipped his tea, pulled on a cigarette, made lists, and received reports from campaign workers who wandered in and out. He ordered people around and, finally, as evening set in, he departed for a lively political assembly, where he and his opposite number, Leventhal, would bash each other.

Once, on a bright afternoon, when work at “headquarters” was going full steam, the door opened and David Sheigitz, in the company of two heavyweights from the tribe of wagoners, appeared. My father was, at first, a bit taken aback. Nevertheless, he managed to greet David with his usual friendliness: “Hello David, what's new?”

David Sheigitz dispensed with preliminaries and went straight to the heart of the matter.

“Listen here, Rav Yankel. I've got something serious to tell you. We the coachmen have reached a decision. We are convinced that only Rabbi Yankele Dayan is worthy of the noble office of Rabbi of Piotrkow. Let me make myself perfectly clear. If you fellows don't stop your support of a stranger, we'll simply have to break your bones.”

He was addressing my father in the plural since, even as he threatened violence, he didn't have it in him to be disrespectful. My poor father turned pale and started stuttering. “David, what is this? What is the matter? Have you gone out of your mind?”

David, however, stuck to his original message. “Rav Yankele, that's it. Remember that you have been warned!”

Then the three musketeers turned on their heels and left without so much as a word of farewell. For months and years later, David Sheigitz avoided both me and my father. (I had been present at the crucial explosion.) Perhaps he was embarrassed. Perhaps he felt sorry or guilty. Perhaps he just could not look us in the eyes again. This was a Jewish Sheigitz, after all.

Such are the echoes of recollection brought about by an old photograph – my memories of the Piotrkow wagoners. I saw a picture of one of them plying his old-world trade in Rishon Le Zion and my thoughts wandered all the way to the election of a rabbi in Piotrkow. All in all, just a web of images from a long-gone childhood; threads of fabric of reflection.

Elazar Prashker – Jerusalem

Glancing through an old issue of Stern magazine (23/1972), I happened to come across the following chess problem (note drawing):

|

|

| A chess problem published by the well known German magazine Stern in 1972 The author is no one else but Leibl Kornfeld of Piotrkow |

The creator of this interesting chess arrangement was none other than Leon Korski, better known to residents of Piotrkow as Leibel Kornfeld, an enthusiastic chess player in our town. Many a time did I test my own chess ability against his, but not once did I even dream of winning. The “discovery” in Stern reminded me that the game of the kings was certainly one of the favored cultural and recreational activities of Jewish Piotrkow. This surely was natural, since chess had always been a popular Jewish game. For some reason or other, this aspect of our lives in Piotrkow was totally overlooked in the original volume of our Izkor Book. This is particularly strange, considering that Jacob Maltz, the initiator and editor of the volume, was, in addition to his many social and political functions, an enthusiastic and dedicated chess player who took part in several competitions in our town. I well remember several of these contests.

At the beginning of the 1920's, the best Jewish chess players held a great, and perhaps the original, chess competition in town. The games were held in the “Tarbut” auditorium on 9 Bykowska Street. The top three places, my memory tells me, were won by Mordechai Frankel, Yakow Maltz and Binem Oppenheim. The judge was Levi Hertzkovitz. Even yours truly participated in the competition as the youngest player, and proudly reached the bottom of the charts.

In the early 20's, “Hashomer Hatzair” also organized the first public game in our town in the yard of the Dobroczynnosc. Yacov Maltz and Mordechai Frankel sat on high platforms on the sides of the playing field, which had been arranged as a chessboard. Hashomer children, dressed in home-designed, colorful costumes, served as live pawns, and I was assigned the job of moving the chess pieces as needed. A large crowd enjoyed the spectacle and the profits went to the summer camp organized by our “ken.”

I will now divulge a secret which Yacow Maltz told me about this game. I never promised to keep his secret and thus I feel free to share it. After all, even state secrets are revealed after a 30-year period, and this particular game at the time of this writing, was played more than 55 years ago. And this is what happened.

Mordechai Frankel and Yakow Maltz, of blessed memory, accepted with pleasure the invitation of “Hashomer Hatzair” to join a chess game which would use live pieces. Everyone in town was extremely interested in the competition. However, it did create certain problems. Who would be the winner? Mordechai Frankel, the best player in town, certainly could not afford to lose. Yakow Maltz, on the other hand, feared that a defeat would wreck his political chances in the approaching elections (and elections, in our town, were always “approaching.”

Diplomatic contacts were made between the competing factions and a compromise was reached. The parties discovered a chess game played in the previous century. The game and its results had been written about in Niva, a Russian magazine from the period of the Czar. This, it was decided, was the game to be played in the “live chess pieces” contest. The game would be pursued for about an hour and a half and terminated with a tie. The deal was made! Everyone involved signed on it and promised to keep the secret. And that is how the chess players actually were turned into actors as they pursued the game with straight faces, all the while following the plans laid out by the century-old game in Niva.

As I consider Niva, I am reminded of how, in our old home in Piotrkow, I once discovered a whole treasury of old periodicals. They were among the first that had been published in Hebrew: the yearly Luach Hachiasaf; Hatsfira (Dawn), edited by Slonimski and Nachum Sokolow; and many issues of Niva. Looking through Niva, I took a particular interest in the many chess problems it featured and I attempted to solve them.

As it turned out, the game of live chess pieces we had in Piotrkow was not the only one of its kind. In Unzer Zeitung (34/August 28, 1936), I discovered the following tidbit:

The Live Chess Match

On Sunday, at 3:30 PM, a live chess match sponsored by the sport club “Shomria” drew a considerable audience. The match was played at the Dobroczynnosc Platz between our very own, very known chess player, Mr. Oppenheim and an out of town guest, Mr. Drozdow. The colorful ,costumes of the “live “ chess pieces were quite impressive. The winner of the match, after an interesting exchange of wits, was Mr. Oppenheim.

Who was Mr. Drozdow? Was he a Jew? Did Jews and Poles ever play chess together in Piotrkow? I don't know the answer, but I am sure that the interest in chess was lively among Jews. In issue No. 37 (Sept. 16, 1936) of Unzer Zeitung. I discovered a column named Chess. I only have a few issues, and I am therefore, not sure whether this was the only appearance of the column or whether there was a continuation of it. At any rate, I would like to return to Leon Korski 's chess problem, which triggered my memories. This sophisticated problem may be enjoyed by any chess fans.

Shmulik in Piotrkow

In 1916, in the middle of World War I, Shmulik Reshevski (Der Kleiner Shmulik) arrived in Piotrkow. He was then six years old and he participated in simultaneous games with Piotrkow's chess players. At the Hertz auditorium on 7 Garncarska Street, Shmulik faced forty chess players, all of the Mosaic persuasion. He also participated in a simultaneous match in the Krakowianka coffee house on Platz Kosciuszki. Here, too, there existed total religious segregation. That is to say, everyone present was not Jewish – with the exception of the protagonist, little Shmulik.

Shmulik became the sensation of both sides of our town. Jews told marvels about him – he was their chief pleasure. This was almost as true among the Poles, who grew effusive about “Maly Shmulik” (Little Shmulik). Dr. Sobanski, a well-known doctor in Piotrkow and an enthusiastic chess player, published a lengthy article in the town's daily, Dziennik Narodowy, predicting a great chess career for “Maly Shmulik.” The prophecy, was, indeed realized: he became a famous grandmaster.

|

|

| Four young men in Piotrkow circa 1915. Who are they? The game of chess was quite popular in our hometown. (From the archives of the “Heker Hatefutzoth Institute,” University of Tel Aviv.) |

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Piotrkow Trybunalski, Poland

Piotrkow Trybunalski, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 28 Aug 2010 by LA