The History of the Jews of Latvia {cont.}

During Soviet Rule (1940 – 1941)

A. General Background

Soviet aspirations to include Latvia within its sphere of influence became a reality with the signing of the Ribbentrop – Molotov pact on 23 August 1939. Less than a year later, in the wake of a Soviet ultimatum of 16 June 1940, several divisions of infantry and tanks of the Red Army entered Latvia. Under the orchestration of Andrei Vishinsky, the deputy peoples' commissar for foreign relations, a new pro-Soviet government headed by Prof. August Kirchenstein was set up immediately, but not one communist participated in this government. The activity of the communist party, which had about 1,000 members, was legally permitted, and its members were given control of various institutions and organizations. At this stage, both the leaders of the party and Vishinsky himself, objected to isolated calls within the party and leftist circles to declare Latvia as a fully fledge Soviet republic. The regime also forbade the seizure of factories, as had occurred previously at the time of the revolution in Russia.

For the time being, the government went no further than to issue ceremonious declarations of close cooperation with the Soviet Union, of civil rights for citizens and of a policy of peace with neighbors. They also issued an amnesty for political prisoners, numbering about 300, most of them being communists and leftists. Military and paramilitary organizations that were essential elements to maintain the previous regime were ordered to disband. This was also the case for religious, nationalist and economic organizations, both Latvian and belonging to ethnic minorities. In the place of daily newspapers, which were shut down, there appeared new newspapers, all of them representing the communist party.

In a short space of time elections were declared for the national Saeima. In theory, it was possible to present candidate lists without any restrictions. In practice, all lists were disqualified, with the exception of the list of the “Block of workers of the Latvian nation,” a list that included 76 members recommended by the communist party. The noisy election campaign was accompanied by festive meetings, concerts, promotional articles in the newspapers and propaganda billboards in the streets. In the course of the elections, the government made some impressive gestures, such as declaration of an 8-hour working day and a raise in salaries of 15% to 20%.

The elections, which took place on the 14th and 15th of July, provided the “Block” with 97.8% of the votes, and of course all 76 candidates were elected to the national Saeima. At its first meeting on the 21st of July, this institution unanimously declared the establishment of a Soviet regime in Latvia and expressed the wish to become part of the Soviet Union. On the 5th August, the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union granted the wish of the Latvian delegation concerning the request of Soviet Latvia to be included in the Soviet Union. From this point onwards there was an intense effort to “Sovietize” the administration, the economy, the education and the culture. Implementation of this effort was apparently the responsibility of three representative groups in Latvia: the Supreme Soviet and its president led by Professor August Kirchenstein, the government (the national committee of commissars) led by Willis Latsis, and the central committee of the Latvian communist party led by Secretary Y. Kalnaberzin. But in fact, the policy was designed by Soviet functionaries who were brought into Latvia and who held extensive powers. Soviet security personnel planned and carried out the mass exile of 32,895 “disloyal” Latvian citizens. They were exiled to Siberia and to other remote places in the Soviet Union. This campaign was carried out in June 1941, about one week before the invasion of the Nazis. On the eve of the Nazi invasion, the Latvian communist party numbered 5,075 people and the Komsomol numbered 6,215. All other political organizations were forbidden by law, but some of them continued to exist underground. Extensive segments of the Latvian population expressed their disapproval of the Soviet regime and opposed it. Both the USA and Britain expressed disapproval of the annexation of the Baltic States and continued to recognize their diplomatic representatives. But this did not prevent the Soviets from maintaining their reign in Latvia up until the German invasion on 22 June 1941, nor did it prevent them from reasserting their reign when they conquered this country again in 1944-45 up until the present time.

[Translator's note: Latvia regained full independence from the Soviet Union in August 21, 1991]

B. The Jews of Latvia under Soviet Rule

1. The Intensification of Anti-Semitism within the Population

During the initial days of the incursion of the Red Army into Latvia there was an intensification of antagonistic feelings of the Latvian population against the Jews. One of the reasons for this, among others, was the enthusiasm and abundant sympathy which many Jews (mainly communists and leftist youth, but including ordinary everyday people) displayed towards the columns of the Red Army. There were also instances where local Jews played an active part in protecting units of the Red Army, or even preventing acts of resistance or provocation on the part of Latvian militias, such as the “Aizsargi,” the “Pērkonkrusts,” and others. Rumors spread in the Latvian army, the police and in right wing political circles that the invasion of the Red Army was initiated at the “invitation of the Jews.” As a result of these rumors, Jews were attacked by civilians and by police personnel. The mood of a pogrom pervaded in a variety of places, especially in small towns. But the expected pogroms did not break out, partly on account of restraint on the part of the instigators and also on account of the measures instigated by the new regime. Nevertheless there were instances of physical injury to individual Jews. There were also vocal conflicts in public places between Jews and Latvians. The Jews felt more personal security. The Latvians were officials or representatives of the old regime or angry citizens who sought an opportunity to be disturbed by the Jews for personal or ideological reasons. The rulers and the communist party feared escalation of the incidents between Jews and non-Jews on account of the coming elections. They realized that their intervention had to be considered and impartial, because they did not wish to appear on the one hand as defenders of the Jews or to lose the votes of the Jews on the other hand. The trades union news-sheet “Proletarskaya Pravda” attacked the anti-Semitism that was rife among the commanders of the Latvian army. One of the most stinging attacks against anti-Semitism on the part of the new regime appeared in the news-sheet of the Latvian communist party “Tsina.”

On the eve of the elections, the demand that anti-Semitism be wiped out was one of the prime election-themes of the communist party among the Jewish public. After the elections, the rulers had no need of them, and this theme disappeared almost completely from their propaganda material. But we should not think that anti-Semitism itself stopped. It is more reasonable to assume that hatred of the Jews continued to exist among a significant part of the local population and that it assumed different forms, generally not involving open and violent attack.

2. Attitude of the Jewish Organizations and Institutions at the time of the Elections

Whereas only a small fraction of the Jewish community actually took part in the displays of joy and enthusiasm that welcomed the Red Army, a much larger number of them were party to the feelings of relief and sympathy for this army. In the political constellation of those times, they felt that any other alternative meant Nazi domination over Latvia. The entry of the Red Army was the lesser of the evils. Indeed there were elderly people who remembered well the Soviet regime in early 1919 and the stringent economic policy, but some of them toyed with the hope that this time the Soviet Union would be satisfied with a liberal but pro-Soviet regime.

Non-religious intellectual circles in the Jewish public, both Zionists and non-Zionists, tended to view the fall of the Ulmanis regime as an end to the almost exclusive control of the “Agudat Yisrael” people over the government education system for the Jews. In their eyes, this control was narrow-minded. The Zionist news-sheet “Unser Wart,” whose publication was permitted several weeks after the entry of the Red Army, welcomed the new government which had already demonstrated a “progressive democratic spirit” as opposed to “the repressive government” of the past. Indeed, up until the completion of the elections, and with a view to receiving electoral support from the Jews, the authorities generally did not take repressive measures against Jewish national organizations, especially not against Zionist and socialist organizations. As noted above, the Zionist news-sheet “Unser Wart” continued to appear with its previous philosophy as well as articles about the land of Israel and routine announcements about the appearance of the chief chazan in the great synagogue, etc. Concerning “Agudat Yisrael,” the new government adopted a very antagonistic stance right from the first days. Their daily news-sheet, the “Yent,” was shut down. In its place there appeared a daily paper with morning and evening editions called “Kamf.” This was a Jewish news-sheet of the Latvian communist party. The majority of its attacks, which were composed in extremist and sarcastic language, especially the caricatures and the diatribes, were directed against the people of “Agudat Yisrael” and M. Dubin, their leader, or against their institutions for Torah education. While the Zionist camp was attacked a lot less than “Agudat Yisrael,” it was clear that these organizations were also marked to be dismantled. In their case, the big question was how they could be dismantled and then to what extent they could be integrated into the new regime. At the peak of the promotion campaign for the elections, “Kamf” published an appeal signed by the Zionist socialists calling for members, sympathizers and all Jewish citizens to participate in the elections on the 14th and 15th of July for the Saeima, and to vote for the only party that promised peace, social justice and equality for all citizens of the country, namely for the “Block of workers of the Latvian nation.” On the eve of the elections, “Kamf” published an article with the title “We warn them” which demanded that the people of “Agudat Yisrael” should “desist from incitement against the regime.“

3. Dismantling of Jewish Organizations and Institutions

Before the elections, the regime limited itself to an energetic propaganda campaign and to fierce denouncement of their political rivals. After the elections, and especially after Latvia was officially annexed into the Soviet Union, extreme measures began to be implemented. Student unions including the national Zionist student unions (“Hasmonai” and “Yardenia” and others), were shut down immediately after the elections. At the same time as dismantling the Latvian national organizations, the Latvian minister of the interior published a decree on the 20th July 1940 about the dismantling of Zionist political parties and other Jewish organizations such as the Jewish “Agudat HaMeshachrerim” (Jewish veterans of the Latvian war of independence) and others. The committees for dismantling the organizations were comprised of Jewish communists and their active sympathizers.

On the 5th August 1940, the day the Supreme Soviet decided to annex Latvia into the Soviet Union as the 14th socialist republic, one of the activists of the former Revisionist party received a telegram from London informing of the death of Zeev Jabotinsky, the leader of the Beitar movement. Since Beitar and the Revisionist movements were already forbidden by law, no public meeting was organized, but “isolated groups of people met in private homes in homage to his memory.” On that day, the commissioner of Beitar in Latvia and Estonia, David Warhaftig was arrested. Even before that, the internal security authorities ordered him to prepare answers to a list of questions that they presented to him. About a week after the arrest of D. Warhaftig – one of the first political arrests among the Jews of Latvia – the chairman of the Revisionist party of Latvia, engineer A. Alperin, was arrested. In mid-October the secretary general of the party, D. Karstedt, was arrested, as was a member of its inner circle, A. Sirkin. On the 3rd February 1941, Rabbi Mordechai Nurok was arrested. He was the leader of “Mizrahi” and he was a former member of the Saeima. Rabbi Mordechai Dubin was also arrested. He was also a former member of the Saeima, representing “Agudat Yisrael,” and he was an associate of the previous regime. In the spring, all of them were sent to prisons or labor camps in remote corners of the Soviet Union.

Unlike the dismantling of the Beitar movement and of the Revisionist party which included the arrest of their leaders, the “Olim” movement and the Zionist Socialist parties were shut down relatively quietly, without arrests, and without much violence. The communal training camps remained in operation for longer than the other organizations, but after a time they were also forced to shut down. Despite the ambiguous attitude of the regime towards the Zionist socialist camp up to the time when they were dismantled, anxiety mounted in the hearts of these people, especially in the country towns. In several places the people decided to disperse, and all the members moved to Riga. Within circles of former members of the Zionist youth movements secret passwords were prepared through which they hoped to inform one another about resumption of the activity of the movement within the framework of liaisons, that is to say underground. However, up until the time that war broke out with Germany, the underground activities were mainly of a social and theoretical nature. This activity affected the actions of members of these groups in the circumstances of the subsequent war, whether they were imprisoned in ghettos or whether they managed to get into the Soviet Union or even within the framework of the Red Army.

C. Deliberations about Integration in the new Regime

Against the background of the general enthusiasm of the Jewish population with the removal of the old regime, and in view of the expectation that the new regime would grant national and social equality for all, a section of the youth sought to take advantage of the new opportunities. Indeed, Jews began to scramble for study in the universities, not to mention study in secondary schools. While social standing and political history played an important if not crucial criterion for acceptance into academic institutions and into other public government positions, it was now possible to overcome these obstacles by active participation in the existing political frameworks, namely the ranks of the communist organization for youth the “Komsomol” and the ranks of the “pioneers” for the very young. In contrast to those who joined up into these frameworks because of the advantages and privileges they afforded, or even because they agreed with them ideologically, there were some who were forced to join up due to various pressures or even threats.

One source of disillusionment for the Jewish public was that Saturdays and other Jewish holidays were not recognized as days of rest, while Sunday, the festive day for Christians, became the day of rest for everybody. It was very difficult even for those who no longer observed the religious injunctions but nevertheless were accustomed to rest on Saturday, to go to work on Saturday. In the course of time, many difficulties arose, including obtaining “kosher” meat.

On the other hand, these feelings of deprivation, whether real or imagined, could not detract from the many advantages that accrued to substantial sections of the Jewish population under the new regime, both directly and indirectly. In addition to the wide range of options for education that were opened for the Jewish youth, Jewish wage earners in various branches of the economy benefited from the new establishment. It is thus no surprise that within circles of the working class and the common people, there was widespread support for the new regime, accompanied by the expectation of further significant improvements in their lot. During those times, a number of Jews who were communist activists or supporters and had been exiled during the Ulmanis regime returned to Latvia. Also others who had participated in the Spanish civil war returned. Jews, who had been active in the underground ranks of the communist party, the “Komsomol” and in circles of their close supporters (among them some who had now been released from prison), were appointed to responsible positions in the institutions of the communist party, in trades unions and in public organizations. There was a significant increase in the number of Jews in the management of government, municipalities and cooperatives where no Jewish worker was permitted in the past. The relatively large number of Jews in the ranks of the police, including the ranks of senior officers, was impressive and constructive in building the self-esteem of the Jewish public. This was also the case in the army where Jewish soldiers were promoted, some of them being given posts as “Politruk,” and some Jewish youth were accepted into the academy for officers known as “The Riga Infantry School.” A very convenient opportunity for young Jewish men and women to integrate into security-military affairs presented itself with the establishment of the militia “Worker's Guard” (Rabotsaya Gvardiya, or the “Gvardiya” for short - see the following). These events were, to a certain extent, an additional cause of rising anti-Semitism among the ethnic Latvians who felt frustrated under the Soviet conquest. We shall see that this anti-Semitism merged with hatred for the Russian conquerors. After the Germans invaded Latvia, these hidden impulsive feelings came out in the form of acts of abuse and in willing cooperation with the Nazis.

The “Gvardiya,” which was established according to a decision of the central committee of the Latvian communist party on the 2nd July 1940, was initially intended to be a sort of secondary police or support force to assist the regime “in the struggle against counter-revolutionary elements.” This organization, which was active in Riga and in other cities, was built according to a military template and comprised about 10,000 men and women. They wore special uniforms, and some of them carried light weapons which had been confiscated from the “Aizsargi” movement.

Not only communists and Jewish members of the “Komsomol” joined the ranks of this organization, but also former members of the “Bund,” “Poalei Zion Smol” (Leftist Zionist workers) and members of former training camps of the Zionist socialist movements. Membership in this organization provided a sort of solution for those youth who were seemingly left in a social vacuum due to the dismantling of the earlier frameworks. Many Jewish members of the “Gvardiya” and holders of responsible positions in the army, the security forces and in the party, subsequently played important roles in the armed struggle against the Nazis during the war, whether in the regular army or in other frameworks.

Cancellation of the study of the Jewish religion, Jewish history, the Hebrew language and Hebrew literature raised feelings of regret, anger and protest among various sectors of the Jewish population. On the other hand, the lively activity of the promoters of Yiddish in the field of Jewish education, which was substantially supported by the regime and by the communist party, gave a ray of hope that there was a chance for a flowering of Jewish culture even if it was in the framework and the program of the socialists. After destroying the Hebrew libraries, they tried to fill the void by setting up new Yiddish libraries, or else by bolstering up existing libraries, but they made sure to purge them of “anti- Soviet” literature. Both “Bund” followers and folkists were integrated to some extent in the effort to develop Yiddish culture. Persons of culture, Zionists and others known not to support the communist camp were not integrated into this effort. The famous historian, Simon Dubnow, was among these.

A “Council for Culture” (Kultur Rat) was appointed to administer the cultural life, the education and the spirit of the Jewish public in Soviet Latvia. The long-standing communist Dr. Max Shats-Anin was chairman of the council and with him were several communist supporters and sympathizers. A political-cultural campaign in the population was inspired by this council through the medium of two news-sheets: the daily “Kamf” (edited by H. Margolis) that appeared from 1 July 1940 until 12 January 1941, and the bi-weekly “Oifboi” edited by H.Leibowitz. S. Konovalov was appointed as head of Jewish education in the ministry of enlightenment (Kommisariat). He was a former member of the organization for Yiddish culture. Teachers and others from leftist circles who were forced out of their jobs during the Ulmanis regime were returned to their teaching or administrative posts in the schools. One estimates that there were 40 Jewish schools (10 of them secondary) in the academic year 1940/41, compared with 62 under the previous regime.

A state-supported Jewish theatre was established to replace the old Jewish theatre of Riga which was now defined as “Teatron Shund.” Among other things, the new theatre was supposed to “represent the joy and the tribulations of the Jewish masses in their progress towards an honorable life.” In Jewish cultural circles the possibility of setting up another Jewish theatre was considered. This theatre would be in Dvinsk, and it would be established with the special help of the actor Sh. Michaels. Several of the works of Yiddish writers in other Soviet Republics were published in “Kamf,” and mainly in the bi-weekly “Oifboi.” Such writers were to be found mainly in republics that had recently been annexed (such as Lithuania and Moldavia). These news-sheets provided not a little information about Jewish cultural life as well as about advances in their productivity. Immediately after the elections, a number of Jewish frameworks were dismantled, frameworks that had operated independently in the political system of the new regime. The cultural-educational activity in the Jewish sector was developed with short-term political aims, and it is doubtful that there was an intention to build an infrastructure of Jewish culture that would exist in the long-term alongside the Latvian culture.

D. Persecution

The policy of nationalization at this time was very detrimental to the merchants and to the small shop-owners. In many cases, the authorities allowed the owners of businesses and factories to remain in their positions, at least for a limited time, and to contribute their talents and their know-how for the new managers. Some factory owners even managed to transfer their capital overseas and to sell some of their movable assets, while medium and small business owners and tradesmen, who did not have assets other than their business, made a profit because there was a great demand for goods. This was because no-one was interested in money, since its value continuously dropped, so they spent it on valuable possessions. In the meantime, the Jewish population of Riga continued to grow. Not only young people came to the city from the country areas, but also shop-owners and members of the middle class, who felt insecure about the new regime in their former places of residence. In addition, Jews who had been political refugees overseas came to Riga.

The tension between the regime and a substantial part of the population increased with the spread of rumors about the imminent outbreak of war between Russia and Germany. As described above, a campaign of exiling “disloyal elements” “en masse” began at day-break on 14 June 1941 in Soviet Latvia and elsewhere. Starting from that night, about 5,000 Jews were loaded onto freight-trains that were destined for the depths of the Soviet Union. In the judgment of the security authorities, these Jews held antagonistic, negative or even doubting views on the new regime. The indications are that the main criteria determining this judgment were: (a) Membership in the past in organizations, establishments or political parties that were outlawed. Special attention was drawn to leaders and activists in these organizations. (b) Belonging in the past to a social class that had high income.

From the this point of view, the first criterion encompassed almost all the leaders of the Zionist movements, including almost all members of the inner circle of Beitar, leaders of the “Mizrachi,” the “Tsionim Clalliim” [General Zionists] and the Socialist Zionists. Members of the inner circle of the “Bund” and previous activists of this movement were also among the exiled. The second criterion was expected to encompass mainly the great merchants, the factory owners and the bank owners, according to all the signs. However, it included people living mainly in the small towns “who never had enough income to support a family with many children.” On the other hand, there were many instances where it passed over some exceedingly rich people and over some well-known factory owners. According to the identity of many of the people who were included among the exiled at this stage, there is almost no doubt that mistakes were made, for example mistakes in identity. There were not a few instances of slanderous betrayal or of “closing of accounts” by persons who were in charge of drawing up the lists. Among those who were forced to help carry out the campaign of exile were members of “Mishmar HaPoalim” [the workers' guard], who were recruited especially for this, as well as specially chosen workers from institutions and factories. A large fraction of the exiled was sent to the Solikamsk, Vyatka and Vorkuta labor camps as well as to other places. Some of the wives, children and family members who were exiled from Latvia together with them were sent to Narym, Novosibirsk, Krasnoyarsk and to other places.

In spite of the bitter experience from the time of the Bolshevik regime in 1918-1919, the Jews of Latvia were apparently not sufficiently aware of the Sovietization of this country in 1940-1941 and all that it implied for private and public-national life. It is very likely that the suddenness of the events and the intensity of the process by which the new regime achieved dominance largely paralyzed any possibility of active reaction. Further, due to the geographic location of Latvia, and to the fact that her borders were completely sealed, those who had the possibility of leaving for overseas or who intended to do so were prevented from achieving such aims.

E. Flight of the masses and the rear-guard battle after the invasion of the Nazis (June-August 1941)

The sudden invasion of the Soviet Union by the German armies (“Barbarossa Campaign”) at daybreak on 22 June 1941 was accompanied by heavy bombing of population centers of Latvia. Two days later, the German forces (“The Nord camp”) invaded the Latvian territory from the south. They met no significant resistance. The forces of the Red Army (the 8th, 11th and 27th armies) were taken by surprise, and were not able to stop the invaders. Within two or three days, most of the Latvian territories on the left bank of the Daugava River were conquered by the German army which continued to move forward in the north-east direction towards Leningrad. When the Germans completed their domination of the whole of Latvia by 4 July 1941, there remained only a few pockets of resistance by the Red Army assisted by local forces. This was the case in Liepaja (which was conquered finally only on 29 June) and other places.

At first, the Soviet rulers vehemently denied the announcements of the German victories. The population was commanded not to panic and to obey orders. But the bombings by the German aircraft, which became more and more numerous, the severe emergency measures adopted by the authorities and the preparations for evacuating state institutions, and above all, the appearance of civilian refugees from areas conquered by the Germans and the sight of army personnel retreating in panic left no doubt that the situation was dire. Further, the general conscription of all persons born between 1905 and 1918 that was declared in the western Soviet Union was not implemented in Latvia, among other things, due to the mass desertion of Latvian soldiers from the 24th territorial (i.e. the Latvian) corps. These deserters, together with other Nationalistic elements (mainly members of the “Pērkonkrust,” the “Aizsargi,” and police personnel) used weapons to attack state institutions and even army installations. Here and there they even caused damage to the panic stricken Jewish community which was left almost without leadership. In view of this situation, the authorities hastily set up front-line units and renewed and bolstered up the framework of the “workers guard.”

The establishment and operation of these units helped raise the morale of the panicking Jewish populace. But many of the Jews who were enlisted in their ranks found themselves tied down to service and guard duties, and in many cases family members were separated from one another during extremely trying times. A debate began in many families: should they remain where they were or move east to the interior of the Soviet Union; was it better to clear out under the wing of a migration organized by a factory or state institution (mainly after 27 June) or was it preferable to flee independently in the wake of the retreating Red Army. The stream of refugees from the Jewish population was comprised of many and varied circles, mainly young people, including those who were suspected of being enemies of the Soviet regime and even some who could expect arrest or exile. In contrast to those who were determined to flee as quickly as possible, and by any possible means and route, there were also Jews, mainly of middle or older age, or those who belonged to the economically well-established strata, who opposed flight to Soviet Russia, whether because they retained relatively favorable memories from the German conquest at the end of World War I, or whether because of the bitter experience with the Soviet regime then or more recently.

The decision to flee, which sometimes involved agonizing choices or fell in the midst of heart-rending family scenes, placed additional problems for the refugees. They had to choose a route and a means of travel. This concerns mainly those who fled at their own initiative and received no assistance from public bodies. In not a few instances special cars were put at the disposal of members of the communist party and high-ranking officials in the Soviet governing machinery for themselves and sometimes also for their family members. They were delivered directly to the border or to railway stations. The main railway routes to the Soviet Union were (a) in the direction southeast via the stations at Rezekne and Daugavpils through the regions of Vitebsk or Velikiye-Luki in Russia (b) in the direction northeast via the Ape and Valka stations through the Estonian territory to Pskov or Leningrad in Russia. After the Germans conquered Daugavpils and the severe damage to the Rezekne junctions, the only escape route for the people of Riga (until it too was conquered by the Germans on 1 July) and for the people of Vidzeme was the northeast route.

The residents of Daugavpils (until it was conquered on 26 July) and the towns of Latgale in eastern Latvia, who intended to flee into the depths of the Soviet Union, had a substantial advantage due to their proximity to the border with Russia. Among the first of the Jewish population who moved out of Latgale were drivers or other workers in state institutions who were charged with accompanying various dispatches to the other side of the border. But the bulk of the Jewish population remained in its place to the very end, until the German army took control of this region, namely until 4 July.

Eastward flight was restricted from the Liepaja area and from the Courland region from the very beginning both because of the heavy fighting and because the authorities strictly forbade it. In the final days of June the flow of refugees came almost to a complete stop due to the distance of the place from the border with Russia and especially because it was cut off by the German army.

Due to the hostile activities of Latvian nationalists, who felt free to act openly against the Soviet forces during the final days of June, and due to the chaos in what remained of the administration, the Latvian Jews were left without protection. There was no one to guide them and nobody knew what to do. Even though there was still a possibility to use trains that travelled eastward, these were few and far between, and on account of severe crowding of the railway stations, only a few succeeded in squeezing into the carriages.

In spite of the bombing, the ambushes and other obstacles on the road, the fate of those who were evacuated in some organized manner or even those who infiltrated between them was without doubt far better than the fate of individuals. The organized evacuation within the framework of the state, a militia, a factory or a cultural or educational organization was by train, or by car, while individuals fled on foot or by bicycle. Many of the latter died at the hands of gangs of Latvians who ambushed them along the road and highways leading to the border. A very small number were picked up by vehicles of the Red Army. Among those who set out on this arduous road under the rays of the blazing sun in July was the communist leader who was noted for his intensive activism in the ranks of the Jews. He was Dr. Shatz-Anin who was blind. An unexpected difficulty in many cases was that the authorities refused to allow refugees to cross the old Soviet-Latvian border. This problem generally lasted for a short time only, but it aroused intense disappointment and emotional crisis for people who arrived here exhausted and on their last drop of physical and spiritual energy.

While the refugees fled, and even integrated with their flight, a bitter rear-guard battle took place in Latvia. This battle was fought by a variety of military units in which many Jewish fighters played a part. One of the main units of battle, the Latvian Soviet army, also known as the 24th territorial corps, was largely disbanded due to the wave of desertion by Latvians. There were even cases where Latvian soldiers turned over their Jewish comrades-at-arms to the Germans. The fate of those who were turned over was no different from the fate of most of the Jewish solders of the Red Army who were taken prisoner by the Nazis – they were executed. Only a few were able to reach Russia through Estonia while fighting fierce rear-guard battles. On the Valdai heights many of them were taken off the battlefront and sent to refugee concentrations in the Ural Mountains.

Many Jews - laborers, engineers, officials and managers – were integrated into the war effort through their place of employment. In this and in other ways many Jews were placed, willingly or unwillingly, in semi-military operations and as a result some of them reached Russia.

The major framework for fighting in Latvia was within the regiments of the “Workers guard,” noted above. A large number of Jews, both men and women, were concentrated in these at that time. The regiments, which were set up and fortified after the 24th June, became regional battle units. Their importance was particularly great in Riga. Members of the “Guard,” some of them in blue uniforms and wearing boots and some with red ribbons on their arms, began by seeing to law and order at vital places in the city - places such as transportation centers, the Post office, bridges, cross-roads, highways, etc. Many of them, including Jews, were hit in the cross-fire between the assorted gangs of Latvians who appeared in various places and opened fire on civilians and on the columns of the retreating army. The women in the “Guard” were active mainly in patrols, in giving first aid to the wounded (from bombing and gunshots), and taking charge of bomb shelters. Circumstances also sent some of them into battle. In Riga, as well as in other places, there were young Jews who were not members of the “Workers guard” and not even members of the Kosomol who joined up with one or another of the fighting frameworks mentioned previously.

After Latvia was conquered by the Germans, the survivors of the “Workers guard” and also of other units transferred to Estonia. Due to its location, the conquest of this country by the Germans was delayed for a long time after Latvia and Lithuania were conquered. After 4 July, it became a place of temporary refuge and regrouping of semi-military forces that retreated northwards from Latvia. The survivors of these units were formed into two Latvian regiments of riflemen who were assigned to the 8th army of the Red Army. These units undertook bitter rear-guard action against the German army and against local nationalist forces. During the first stage (July-September 1941) these two regiments fought mainly within Soviet Estonia. In the second stage (September-October 1941) the Latvian regiments took part in the fighting near Leningrad. The fraction of Jews in their ranks was substantial, and is estimated to be 30%. Among them were also some refugees who were trapped in Estonia in their flight from Latvia.

In the summer of 1941, individuals and small groups tried to get out of Latvia in one way or another, in the wake of the retreating Red army. There were two hordes of Jews: those being evacuated and those fleeing at their own initiative and fighters. It appears that about 5,000 of them died in battle as a result of the fighting, the bombing or murders. It is therefore estimated that about 15,000 managed to get into the Soviet Union. According to Soviet sources, a total of 40,000 Latvian citizens were evacuated or fled from that country.

F. Life of the Jewish refugees in the Russian interior

Even when Latvian Jews reached the unconquered Soviet territory, many of them still died in bombings and in other war activities. In general, the refugees had no idea of their ultimate destination; even those evacuated by the authorities did not know this. Those who were fleeing grabbed hold of any means of transportation or even continued further on foot – anything to get away from the German armies that were advancing after them. It is possible to describe schematically the main routes of flow of the majority of refugees from Latgale as follows:

- From Rezekne in Latvia through Velikiye-Luki to the central Volga low-lands, and from there to the southern Ural mountains and to the southern areas of Siberia or to central Asia.

- From Pskov near the Latvian border through Dno-Bologoye to Yaroslaval, Ivanova and Kirov.

- From Estonia or Leningrad (places they reached via various routes, including by sea) by train mainly to western Siberia.

At least initially, the fate of those who were evacuated in an organized manner by the authorities was better than the fate of those who fled at their own initiative. Thus, for example, housing and jobs were arranged relatively quickly for the workers of the airplane factory, some of whom were evacuated from Riga to Kazan on the Volga. Similar arrangements were made for graduates of several trade-schools. Workers of state institutions and services, police personnel (militia men), army servicemen, party activists, graduates of trades and other schools and in particular hundreds of “pioneers” who were evacuated directly from their summer camps in Latvia received especially dedicated treatment at the behest of the authorities. Special schools were established for the latter, and also for other children from Latvia.

Among the “non-organized” refugees, there were prominent small groups consisting of family members, or people from the same town, or members of a youth movement or former pupils from a school, who made an effort to stay together under all conditions. Initially, a large fraction of the refugees were accepted into Kolhoz collective farms. They were integrated mainly as agricultural workers and barely earned enough to provide for their needs. But the duration of their stay on the Kolkhoz was short, especially in the region of central Russia. This was caused by two central factors affecting their lives at the end of the summer of 1941: the mass migration southwards to central Asia and conscription into the army. The southward mass migration encompassed not only refugees from the Kolkhoz, but also those in small towns. Without doubt, one of the main reasons for the migration was the approach of winter which was indeed extremely hard in 1941. Another reason for the immense non-stop waves of migration to Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and other republics in central Asia was the fear of the almost continuous advance of the German armies. As an example, of the 9,500 Latvian refugees who were in the Yaroslavl sector near the front in July 1941, only 1,500 remained by December of that year. Even then, the condition of most of the refugees in the Asian republics was far from good. Both in the large cities like Tashkent, Stalinabad, Ashkhabad, Fergana and others, and also on the Uzbek and the Kyrgyz Kohkoz collectives many of them suffered from starvation and severe want. Many refugees, especially the elderly and infants, died as a result of these hardships and also from typhus which broke out in the city slums and in the villages of central Asia and reached the proportions of a major epidemic. This resulted in a rise in the number of orphans among the refugees. Families without a head were also in a very bad state up to the point of despair.

The condition of Latvian refugees living in central Asia and elsewhere in Russia improved very slowly, partly as a result of aid that reached them from overseas also via Teheran in Persia. Public support activities among the Jews of Latvia, especially in the form of monetary or other aid, became apparent in the second half of 1942. One of the first activities of Rabbi M. Nurock, who was released from jail in April 1942, and settled in Tashkent, was to secure a license from the local authorities which permitted a group of volunteers to attend to everything connected with the local Jewish cemetery. They were a sort of “Hevra Kadisha,” and they extended and maintained the cemetery. The activity of financial support for the Jewish refugees in Tashkent was organized with the personal support of Rabbi Nurock, of Zalman Shalit from Riga and of others, using money that came mainly from overseas. A similar support activity that was restricted to persons from Latvia and to members of the Chabad movement was developed in the same way in the city of Kuybyshev by Mordekhai Dubin. He lived there after he was released from jail in July-August 1942.

In the course of time, the Latvian government which was located initially in Kirov and later in Moscow, provided support for Latvian refugees. They did this either directly, or through 11 agents (franchised representatives) who operated in 20 sectors and republics across the Soviet Union, but mainly where there were large concentrations of Latvian refugees. The support took various forms. They distributed shoes, clothing, and textiles and issued cash grants to needy families from Latvia or to individuals, especially to wounded soldiers or to war invalids. There were also young people who were assisted by the Latvian government to gain entry into universities and other institutes of learning. A considerable number of Jews who held high positions in the party hierarchy of Latvia were able to escape into the Soviet Union and to continue their political or state careers. Examples of this were B. Berkowitz, B. Friedman, Dr. Yaffe and others. The blind Dr. Shatz-Anin, who travelled on foot as mentioned above, reached Kazakhstan safely and was appointed to the post of lecturer and senior researcher at the institute of science in Alma-Ata. [Translator's note: Alma-Ata is now called Almaty]. In the course of time he was seconded to the “Jewish anti- Fascist Committee” and took part in the propaganda campaign to persuade the Jewish nation to provide moral support for the war effort of the Red army against the Nazis. With this aim, the anti-Fascist committee approached the former prisoner Rabbi Nurock, and asked him to write an appeal to the Jews of the world. Indeed, he responded positively to this request, and even organized a day of collecting money among the Jews of Kazakhstan to purchase an airplane for the Red Army.

A strong desire to get out of the Soviet Union and to go to the land of Israel was felt among the refugees, especially among those who belonged to the Zionist camp. The desire included a willingness to cross the southern border of the Soviet Union illegally. One of the first groups, consisting of four members of the former Beitar movement, who actually attempted to do this and reached Ashkhabad [Ashgabat] in July 1941 with the intent of crossing the border into Iran (Persia). All of them were caught, and they were each sentenced to 10 years in prison and to 5 years in exile. Two of them died of starvation and exhaustion due to the conditions of their imprisonment. In spite of the cloak of secrecy that shrouded these cases, it is known that a similar fate befell tens of Latvian Jews who attempted to leave the Soviet Union in this way. In spite of this, efforts of individuals or of groups continued in various directions, seeking to promote the possibility of immigrating to the land of Israel at a suitable time, or at least to make preparations for this. One of these groups, from within the circles of HaShomer HaTsair - Netsah, operated for some time in Tashkent. It was led by Shmuel (Mulla) Yaffe and Yaakov Yankelowitz (Yanai). Their activities were based on maintaining contact with the Zionist movements among the refugees from Latvia. In the final stages of the war, and mainly after it, the kernel of this group took part in the general “flight” from Europe to the land of Israel. Their activity centered on the remnants of the Jews in the Baltic States. During the period of the war (1941 – 1945), there were only a few isolated cases where Jews from Latvia managed to get out of the Soviet Union, either through the framework of the Polish army of General Andres, or in other ways.

During the first few months of the war between Germany and the Soviet Union, and especially during July and August of 1941, hundreds of Jews from Latvia served in ad hoc military units, particularly in the regions of Estonia and Leningrad. Not a few of them took part in battles and were injured or killed. In spite of this, the authorities prevented Jewish Latvian refugees from enlisting in the Red Army. The main reason for this was the excess suspicion with which they regarded persons originating in western culture (“Zapadniki”), which included refugees from Latvia. However, in many instances, the immediate military urgency was overridingly in favor of enlisting them. There were also cases where the strict orders did not reach the units where refugees were accepted, and they were enlisted either through recruiting offices or directly into the units. A dramatic change took place in this situation when the Latvian division number 201 was established in the Red Army in August 1941. Multitudes of Jews from Latvia answered the calls for conscription and for volunteers that were published at concentrations of refugees from this country. Consequently, in the initial stages of organizing the Latvian Division in the camps at Gorokhovetsk, the Jews outnumbered the other ethnic groups (Latvians, Russians, Poles and others) who served in this unit.

In the course of three years – from its being organized in autumn 1941 until its entry into Latvia together with other Soviet units in the autumn of 1944 – Latvian division 201 took part in a long series of hard battles, among others, the defense of Moscow and Naro-Fominsk, in the regions of Demyansk, Staraya Russa, Velikiye Luki and more. The division was given the title “The Latvian rifleman division of the 43rd guard” for its distinction in the battles. Due to the heavy losses suffered by the division in its battles, its ranks were filled by local reserve soldiers. As a result, there was a gradual reduction in the proportion of Jewish soldiers within its ranks, which continued until the end of the war. In May 1944, another Latvian division was established, division number 308. Together with the previous division, the two made up the Latvian rifleman corps number 130. Of the 16,000 soldiers in this corps at that time, the Jews made up at least 8%. Thus about 1,300 Jewish soldiers were privileged to take an active part in freeing Latvia from the Nazi conqueror. If we add to this the Jewish soldiers who were absorbed into the Latvian corps of the Red Army during the course of the war, for example new recruits who were obliged to join up each year, soldiers transferred from other units, etc., we can state that at least 4,000 Jewish soldiers served in the Latvian corps of the Red Army during the years of its existence. Half of them died in battle, and of the rest, the number of wounded and invalids was very high.

G. The fate of those Exiled into the Soviet Union (1941 – 1945)

In addition to the 15,000 Jews who managed to reach the unconquered territories of the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941, some at their own initiative and some evacuated by the authorities, about 5,000 Latvian Jews were already there, those who had been arrested and exiled as “undesirable elements” just before the outbreak of the war with Germany.

The vast majority, either as heads of a family or as individuals, were incarcerated in “labor camps for the correction of criminals,” scattered all over the Soviet Union. In point of fact, these were isolation camps. Among them were ViatLag (the camps of Viatke) in the Kirov sector. Many of the Jews of Liepaja and the towns of Courland and Latgale were brought to this place. Some of the Latvian Jews were sent to the camps at Vorkuta in the autonomous republic of Komi in the far north of European Russia, and some to other places. A great many of the heads of family or individuals who were arrested, mainly in Riga and Daugavpils, were concentrated initially in the Yuchnovo camp in the west of European Russia. As the German armies advanced into the heart of Russia, the prisoners were loaded once again onto freight cars, and were taken to the camps at Solikamsk northeast of the city of the Molotov sector (Perm). Within a few months nearly two thirds of the prisoners in Solikamsk died of disease, starvation and the hard labor in the forest. A similar rate of deaths occurred also in the camps of Viatke (ViatLag), Vorkuta, Reshoty and other camps where Latvian Jews were imprisoned. Those who were among the first to die were afforded a burial by their comrades, a burial that was reasonably honorable considering the circumstances. As time went by, the number of dead increased so much that those who remained alive were unable to fulfill this duty. Their condition had badly deteriorated and they no longer had the necessary physical and spiritual strength. The tens who died each day were buried in communal graves. A small fraction of the prisoners were privileged to receive some help, though not for an extended time. Members of their family (some exiled and some refugees) were able to locate the prisoners and to send them parcels of food or clothing.

In the spring of 1942, after most of the prisoners had died, the security authorities began to investigate the cases of the few who were still alive. This was done through an institution called “Special Consultation.” A team of three functionaries, called a “Troika,” passed judgment on each prisoner, not in his presence. Most of the prisoners from among the Jews of Latvia were accused of being “socially dangerous people.” This was due to their having been factory or shop owners. Others were accused of “anti-revolutionary activity,” this on account of belonging to a Zionist party or to a social democratic party, such as “Bund” or similar, all of this in the pre-Soviet era. Confessions were extracted from the accused following non-stop night questioning after which the tortured accused would generally sign anything that he was asked to. In the course of lengthy investigations, sentences were passed on all the prisoners who were still alive in the months of June to September 1942. Most of them were sentenced to exile of five or more years, mainly on account of political-public or economic activity in the time before the Red Army came to Latvia. Generally, they sent those sentenced to exile to remote places in Siberia (“Silka”). It sometimes happened that they came to the same places where their exiled families were sent, and perhaps even met up with them. Beginning in 1943, some heads of family who fell seriously ill while in labor camps were pronounced invalids unfit for labor and also reached “Silka.” The total number of prisoners who were released from the camps (either by way of sentence or being pronounced invalids) was very small, and most of them did not survive for long after their release.

The majority of those arrested in the course of the campaign of exile were imprisoned in labor camps, as described above, whether they were single or heads of families. At the same time, their families and all others who were rounded up were exiled or forcibly sent to settlements in the depths of the Soviet Union. Officially, these exiled persons were called “Special Settlers.” Initially, most of them were concentrated in the interior regions of Siberia, and from there they were taken up north. Considerable numbers of exiled persons from Latvia were also concentrated in Krasnoyarsk, Turukhansk, Narim, some sectors of Tomsk, Molotov (Perm), Kirov and other places. In the course of time, they were scattered northwards towards the Arctic sea and eastwards as far as Vladivostok.

Immediately upon arrival, as soon as they were housed in the villages, the newly arrived settlers were obliged to begin working. Most were assigned to agricultural work, to factories and to felling trees in the forest, while a small minority was assigned to professional or clerical jobs. In many cases, the work place was a considerable distance away, and they were required to go out and return on foot. The work itself was extremely difficult. The payment was too small to buy bread on the black market. No less important were the ration cards for food, given to the workers. On account of hunger, the ration cards were the main motivation to work. The sick and the elderly were not forced to work, but they depended for sustenance on the support of their family or on the sale of personal possessions if they had any. Those who lacked possessions and who had no one to support them died of starvation or of disease. Whole families were wiped out in this way. In spite of this, there were families, and even families with many children, that survived the critical phase of the first few years as “Special Settlers.” This was thanks to the spiritual and physical strength of the family members that enabled them to survive the harsh conditions that were imposed on them. Some made clearings in the forest where they grew potatoes and vegetables. Some proved themselves through positive initiative in the execution of their duty with the result that they were given jobs that required special skill and responsibility. This resulted in an improvement in their conditions of living. In the course of time, the “Special Settlers” and to some extent also the prisoners in the labor camps were helped by parcels that they received from relatives, from friends and from aid-organizations in the land of Israel, in America and in other overseas countries. The federation of immigrants from Latvia and Estonia in Tel-Aviv gathered about 4,000 addresses of Latvian Jews all over the Soviet Union, and became a most important center for aid and for communication. In contrast with heads of families and single persons who were as aforementioned charged with political and social crimes, their families and other elements of the “Special Settlers” were not charged, but nevertheless were bound to their places of exile. In spite of the difficult conditions of living and the severe hunger that were present, especially in the first years, the young persons took advantage of every possible opportunity for education that was within their reach and where the doors were not shut before them. This was the case with primary schools, high schools and even universities. In this way, many of them acquired academic professions that were in demand, mainly in the natural sciences, and even became integrated in the work-force in their fields of expertise. In their places of work most received the same privileges as their colleagues, apart from a set of restrictions due to their status as “Special Settlers.” In general, only a few were accepted into the army. These were drawn mainly from the second generation in the later period (1944).

Two persons were released from their imprisonment during the course of the war, (apparently because highly influential elements from overseas interceded on their behalf). These two were personalities who held prominent positions in the life of the Jews of Latvia and who had served on the Saeima. They were Rabbi Mordechai Nurock, a member of “Mizrahi,” and Mr. Mordechai Dubin, a member of “Agudat Yisrael.” Rabbi Nurock went to live in Tashkent in Uzbeckistan. Mr. Dubin settled in Kyubishev. A committee was established by the Latvian government shortly after the war (in 1946), which operated throughout Siberia and in other parts of the Soviet Union with the purpose of locating children, especially orphans, who originated in Latvia and returning them to their homeland. Many young Jews tried to take advantage of this opportunity, and some of them even succeeded. In 1948 steps were taken that seriously worsened the state of political prisoners. Almost everyone who completed the term of his imprisonment at that time automatically became an exiled person forever. In this manner, many persons who had been exiled from Latvia, but somehow managed to return to Riga by using some ruse or other, were arrested once again. They were returned to Siberia in the carriages of the prisoners.

A change for the better occurred at the time of the “Thaw” after Stalin died. Among other things, the files of the prisoners, of the exiled persons and of the “Special Settlers” were re-examined. The process of releasing sick prisoners from the camps was accelerated. Sentences were reduced. A new concept came into being: “Cleansing” (Rehabilitation). However, many were “cleansed” only after their death and a pitiful compensation was paid to their families.

In the spring and summer of 1956, the “Special Settlers” from Latvia were released on a more massive scale. The first to be freed were those who received awards of distinction from the state, as well as all the teachers. They even received “clean” identity cards. Some of the men among them received ID booklets of soldiers. Nevertheless, it was forbidden for them to live in Latvia. The remaining “Special Settlers” were released several months later. In spite of the prohibition to return to Latvia, especially not to Riga, many returned to their homeland. Most concentrated in Riga, and with few exceptions, no steps were taken against them. By the end of the 1950's the majority of persons who were exiled from Latvia and who were still alive returned to their homeland. The remainder, between 1,500 and 2,000 persons (that is 20% to 30%), died of disease, starvation and other privations in the labor camps and in the places where they were exiled.

Under the Nazi Conquest (1941 – 1945)

A. Regimes of Conquest, their Types and their Characteristics

For several weeks after the conquest of Latvia by the Nazi German forces (end of June and start of July 1941) the country in general was ruled by the military. Many places, mainly small remote villages, fell into the control of local Latvian or other forces. At the center of these forces were former military or police personnel, and also personnel from nationalistic movements such as the “Aizargs” and the “Perkonkrust.” Several of the leaders of this movement, for example G. Celmiņš, and other persons from the extreme right wing camp who had found refuge in Nazi Germany now returned to Latvia with the blessing of its military rulers, with the aim of taking part in the new political situation that was created there.

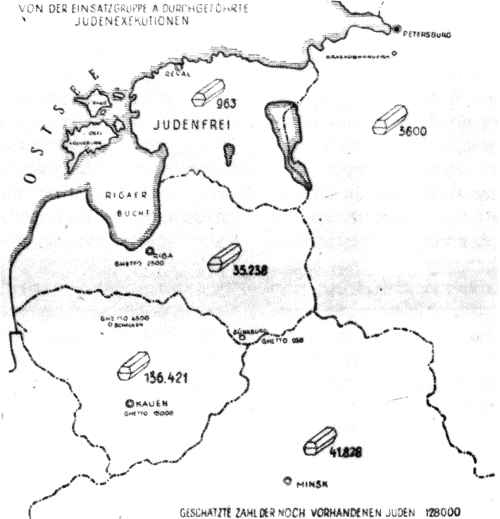

A great number of personnel of the civil administration, and of various security institutions came into Latvia together with the columns of the German army, and also following it. Among these was “Einsatzgruppe” A (assignment division A) under the command of brigadier-general Franz Stahlecker of the SS. This division was one of four divisions of its kind that followed the German army into the parts of the Soviet Union that were conquered. The divisions were generally composed of personnel from the security services, security police, and general police and from the “Wafen SS” [Wafen means weapon, SS is the abbreviation for Schutz Staffel, (Hitler's) protection corps, so Wafen SS means armed protection corps.] The purpose of the divisions was to root out and to destroy communists and all other elements considered damaging or dangerous to the Nazi regime. Their prime target was the Jews. They were authorized for this by a command of the Fuhrer, Adolf Hitler, of March 1941. The command stated that the future war with the Soviet Union (code named “Operation Barbarossa”) would require complete extermination of “Jews, Gypsies, persons of inferior race and other asocial elements, as well as political commissars” in every conquered region.

Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia as well extensive parts of Belarus and the surroundings of Leningrad were designated as the zone of action for Einsatzgruppe A. A secondary unit, called Einsatzkommando 2, was stationed in Latvia proper, and was responsible for most of the action there. Its commanders were: SS-Sturmbannführer Rudolf Batz [assault (or storm) unit leader], SS-Obersturmbannführer Dr. Eduard Strauch [senior assault (or storm) unit leader] up till 3.12.1942, and subsequently SS-Sturmbannführer Dr. Rudolf Lange. He further filled the position of commander of security police and security services in Latvia (Kommandeur der Sicherheitspolizei und der SD für den Generalbezirk Lettland). The general commander of the police and of the SS in Latvia was Brigadeführer Shröder. The latter was under the command of the supreme commander of the SS and of the police in Ostland, SS-Gruppenführer Friedrich Jeckeln. All of these played a prime role in the process of destroying the Jewish population of Latvia, as detailed in the following.

On the 17th of July 1941, Latvia, together with Lithuania, Estonia and Belarus were decreed to be one of four main regions (Generalbezirk) that comprised the Commissariat of the Reich. It was called the “Ostland Reichscommissariat” with its center in Riga. Generalbezirk Lettland consisted of 6 administrative regions (Gebiet) with a regional commissar (Gebietskommissar) at the head of each. The regional commissar was under the command of the general commissar (Generalkommissar). The latter post was filled by Otto-Heinrich Drechsler. He resided in Riga.

In spite of the enthusiasm with which the Latvians received the German army, and even though there was a close connection between nationalist Latvian circles and the Nazis from earlier years, the independent Latvian republic was not reinstated. Latvia was granted independence in its internal affairs in 1942 in the form of a general committee (Generalrat) with the former commander in chief of the Latvian national army, Oskars Dankers, at its head. The governing body of the conquerors established military and police forces composed of Latvians, with the objective of helping the German war effort and furthering various political aims, including the wiping out of the Jews. Among the forces were: a Latvian SS legion comprised of 3 divisions (about 30,000 men); the auxiliary Latvian police, comprised of about 9,000 men; police battalions and “self defense” regiments as well as other auxiliary units.

While the truly military units were deployed mainly at the Soviet war-front, the remaining units, mainly the various police units, were employed to destroy the Jews of Latvia, Soviet prisoners of war and Gypsies. The German governors also made considerable use of them for acts of murder and punishment in various places in Eastern Europe such as Poland and Belarus. Police regiment 18 was particularly infamous in this respect, as well as various other police units, in particular Commando units. Latvian officers Voldemars Veis, Roberts Stiglics, Victors Arajs, Herberts Cukurs and others were the leaders of some of these units. Most of them came from the ranks of the right-wing nationalist militias of earlier times, such as the “Aizargs,” the “Perkonkrust,” the national Latvian army and the police force.

The Latvian police forces and the various Latvian security forces were in fact under the control of the general commander of the SS and the German police. In addition to soldiers, security personnel and police personnel who came into Latvia from Germany during the period of the conquest, there was also a concentration of thousands of German citizens, including persons born in Latvia, who were active in political, administrative and economic circles. Among them were also German-born long-term residents of Latvia, who were transferred to Germany according to the terms of a special agreement in 1940. It was the intention that the German citizens, or at least some of them, would be colonizers and would strengthen the German ethnicity and culture in the long term, in addition to their tasks within the governing administration. As for the Latvians, the plan of the Nazis was to give them second rate status in the long run.

The Latvian nationalists certainly did not have a favorable opinion of the German policy in their country. On the one hand, this policy nullified (at least for the duration of the war) any chance of rebuilding an independent Latvia, and on the other hand required that they take an active part in the war effort. An indirect benefit for the Latvian nationalists was that it afforded them a chance to take revenge in blood on those who they saw as “the enemy from within” – communists, leftists and mainly on the Jews, who they could now rob and from whom they could inherit. In the daily newspaper Tevija (The Homeland), which began to appear immediately after the Nazi conquest, articles with titles that speak for themselves were published almost every day: “The plans of the Jews to divide up Latvia,” “What Adolf Hitler has to say about the Jews,” “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” “Jewish power will be destroyed – Europe will be saved,” “Living without Jews” and others. In an article that appeared on 11 July 1941, with the title “The Jews are our destruction,” it was explicitly stated that “the Jews who wanted to destroy our nation must now all die.” After the frustration under the Soviet regime, the desires and interests of the Latvians at this point in time were identical with those of the Nazis – destruction of the Jews in the framework of “the Final Solution.” In fact, the infrastructure to carry this out had already been prepared for the Jews of Latvia. The combination of this background and the geographic location of Latvia sealed the fate of the 70,000 Jews who remained under the regime of the Nazi conquest. This regime came to its end in eastern and central Latvia with the return of the Red Army in October 1944. In Courland, the German divisions (which included the Latvian units) held out until May 1945 – the day when Nazi Germany capitulated.

B. Pogroms, Murder and Decrees against the Jews

Already, in the final days of June 1941, while the Red army was waging a desperate war of retreat in Latvia, armed militias organized themselves in many cities, towns and villages of Latvia in the name of “self defense.” The organizers and leaders of these militias were mostly former members of organizations such as the “Perkonkrust” and the “Aizargs,” but the bulk of the members were from very mixed backgrounds: clerks, students, school-children, tradesmen, merchants, farmers, artists and laborers. Their ranks included former military officers, policemen, detectives and even some who were active communists prior to the outbreak of hostilities. One and all, they now wore armbands with the color of the national flag of Latvia, fell upon the retreating Red Army, and stripped the dead and wounded of their weapons. But their main activity was to incite pogroms against the Jews and to express “the anger of the Latvian nation” against them on account of the co-operation of the Jews with the Soviets. Among their first victims were the Jewish refugees who tried to flee to the Soviet Union, were blocked by the German army, and were therefore forced to return to their homes.

As the German army entered Riga and other cities, the wave of pogroms reached their peak in the early days of July 1941. The rioters went from house to house, robbed, assaulted and butchered whole families and individuals. The murders and acts of violence continued for weeks in most places. Campaigns of mass arrest were also carried out against the Jewish population. Those arrested were dragged to the jails and the police stations, where they were tortured and humiliated. In many cases they suffered starvation and thirst. Some were detained out in the open and some in cellars. Each day they took out large groups of men and murdered them. While the terror was being enacted against the Jews, synagogues and Batei Midrash were desecrated. Many persons who happened to be praying when found were executed. Many women were raped and then shot immediately afterwards.

At this time it was also a common practice to kidnap Jews from the street or from their homes, not only to kill them, but also to force them to work for the Germans. Neither the kidnapped persons nor their families knew what the purpose of the kidnap was or whether the persons would return home. This raised the feeling of panic among them even further. During the forced labor, the Germans and the Latvians maltreated the Jews and beat them mercilessly. It was therefore extremely dangerous for the Jews to venture out into the street at this juncture. In addition to all this, they were forbidden to enter shops and grocery stores. As a result, starvation threatened many Jewish families. Their source of income disappeared, because Jewish workers and heads of family were immediately driven out of their places of work, and they were not paid even a penny of the wages that were owed to them for their work in the past. The Jews were abandoned, defenseless and with no one to protect them. German soldiers and officers, hooligans and criminal elements took advantage of the terrible situation of the Jews to rob and plunder them. They would break into Jewish homes with threats, and then rob them of whatever they wanted. The Jewish victims were “grateful” that they suffered no bodily harm. Conditions became so extreme that the German military regime found itself forced to post printed warnings in the city streets to the effect that any person caught for robbery, whether soldier or citizen, would be put to death. Even this was ineffective, and the robberies continued as before. In this respect the Jews of Riga suffered greatly. There was almost no family that was not robbed.

Murderous pogroms, burning down of synagogues and other sinister actions took place at this time, not only in Riga, but also in Liepaja, Daugavpils and in smaller population centers in the provinces. There is no doubt that this wave of murders that broke out in all of Latvia was in accord with the plan of annihilation of the German regime. Among other things, the pogroms were to demonstrate to the whole world that the local population took drastic steps against the Jews “as a natural reaction to their being subjugated by the Jews over tens of years.”

The number of victims who died in the course of the pogroms of July 1941 apparently reached about 5,000. To be quick and efficient in carrying out what the Nazis called “the final solution to the Jewish problem” mass executions began that very month in a systematic manner and following a precise timetable. Various advance preparations were made in several places, such as confining the Jews to their homes as in ghettos. A systematic act of murder that was carried out in a particular place was called an “Aktion” by the Germans and “Akzia” by the Jews. An “Aktion” generally followed a number of steps such as: concentration of the victims through threats of beatings or by murder of a few individuals, transport either on foot or by vehicle to the site of murder, execution by shooting at the side of a pit or a trench that was prepared in advance, collection of “booty” from the bodies (clothes, jewelry, etc.), the covering of the trenches. In some localities both the local Jews and the Jews from nearby localities were executed in the course of the “Aktion.” Sometimes the “Aktion” included a careful “Selektion” in order to identify those Jews with professions or appearance that made them fit for physical work. These were then temporarily returned to their homes with the intention of using them as forced labor for local needs or for the war effort. The rest, mainly the elderly, the sick, the women and the children were executed.

The Latvian auxiliary police (battalion 18) and other units, such as Kommando Arajs under the command of Viktor Arajs, played a major part in every kind of “Aktion.” The spearhead of all this activity was a group of 180 men drawn from Einsatzkommando 2. In the months of July and August they exterminated almost all the Jewish residents in the country towns using methods of extreme cruelty. For example, they gathered the Jews of Tukums, Kandava and Jelgava into the synagogues and burned them alive. In other places, such as Zilupe, Preili and Rezekne, they concentrated the Jews in the central plaza of the town and afterwards shot them in the nearby cemetery or forest. In general, the Jews were commanded to undress and then stand or kneel at the edge of a pit that had been prepared beforehand. Then they were mowed down by fire from a machine-gun. In this manner hundreds of people, some Jews, some Latvian communists, some women and some children, were shot dead by Latvians under the supervision of German security personnel on the 12th August 1941 in the vicinity of Aluksne. In the same month, Jews from Gostini and from Krustpils were murdered, in the district of Krustpils, as well as Jews from the following places: Karsava, Kraslava, Vilani, Varaklani, Livani and Indra. It was no idle boast that large signs appeared at the entrance to several Latvian towns advertising that they were “Judenrein,” that is to say “free of Jews.”

The prevailing conditions were such that the Jews could turn to no one for help of any kind, not even spiritual support. No Jewish institution or organization existed in all of Latvia, as all of them had been wiped out in the year of Soviet rule. It was now hazardous to gather and try to garner advice on what to do and how to stand up before the enormous danger that faced every Jew outside. And thus, while some of the Jewish leaders were previously banished into the depths of the Soviet Union, and others were murdered in the course of the first pogroms, the Jews of Latvia were left almost completely without leadership, and they were utterly cut off from the Jews of the rest of the world.

On the 13th August 1941, while rioting against and murder of the Latvian Jewish population was already in progress, the German civil government issued “provisional instructions for dealing with the Jews.” Ironically, some of these instructions had already been put into effect. In order to clear up any doubt and to prevent any misunderstanding, it was stated at the head of these instructions that their sole purpose was “the taking of minimal steps” by the regional commissioners (Generalkommissare) and by the district commissioners (Gebietskommissare) in their respective jurisdictions up until the time when the steps for a complete resolution of the “Jewish question” were put in motion: i.e. the physical destruction of the Jews. A part of these instructions are presented here, with minor deletions.

- A Jew is any person who has at least three fully Jewish (Volljude) grandparents by race. A Jew is also any person descending from two fully Jewish grandfathers or grandmothers by race, or who is a member of a community of the Jewish religion, or who on or after 20.6.41 was married to or who lived with a Jew or a Jewess.

- It is ordered that Jews be marked at all times by a yellow six pointed star visible to the eye with minimum size 10 cm. to be worn on the left chest and on the center of the back.

- Jews are forbidden: to change place of residence unless given permission by the district (city) commissioner; to use the sidewalk; to use public transportation… and private cars; to use places of relaxation; to use places designated for the public (for example: spas and public baths, public gardens, lawns, sport fields and playgrounds); to visit theatres, exhibition halls, libraries and museums; to attend any kind of school; to own a car or a radio receiver; to perform schita (kosher ritual slaughter).

- Jewish doctors and dentists are permitted to treat or advise only Jewish patients. Pharmacies that were up to now managed by Jews had to be turned over to “trustworthy” management, which meant to be turned over to Aryan pharmacy owners. Jewish veterinarians were forbidden to practice their profession.

- Jews are forbidden to practice: as lawyers, as bankers, as money changers or to issue loans with interest, as agents for the sale or rental of estates, as peddlers of various kinds.

- The property of the Jewish population is to be confiscated and placed in safekeeping… The district commissioners will issue orders for the immediate surrender of the following: local and foreign currency, stocks and bonds, jewelry and other valuable articles (for example gold and silver medals or coins, expensive metals and jewelry, gemstones and similar items).