The Final Journey of Jacob Drapekin:

Confirming a Myth with a Missing Matzevah

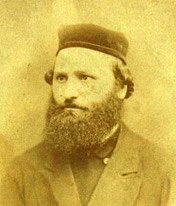

Like most children, I grew up with stories. Among my culturally assimilated, non-Zionist family, the most persistent—and untraceable—story was that my mother’s grandfather, after spending many years in America, “died on a ship to Palestine, and that’s where he’s buried.” The only fact was that there were no facts: no dates, no documents, no clues. It seemed so unlikely. His daughter and sons had shown little interest in Israel, and so far as I could tell, not even a blue-and-white box like my father’s parents. When my husband, a Reform rabbi, wanted to return to Israel in 1977 to show me where he had studied for a year, I was the first—except for my mythical great-grandfather—on both sides of my family to go. In Haifa, we found an abandoned cemetery across the road from the old port. The stones ranged from difficult to impossible to read. Many were shattered; all were covered with weeds and vines. A self-appointed watchman asked for shekels to say Kaddish, assuming we American Jews could not, but he could give us no information. Late one night in 2005, I typed my great-grandfather’s name into Google. On the screen appeared: “It was on the 24th day of March that one of the passengers—Mr. Jacob Drapekin of Chicago, who was making the trip to spend his last years in Palestine ...” One click led me to the diary of Herman Hirsch. His great-grandson, Arthur Hirsch, had transcribed the diary and put it on his personal website. Herman Hirsch had been a passenger on the SS President Arthur on its maiden voyage from New York to Haifa. Among other events he recorded: “It was on the 24th day of March that one of the passengers—Mr. Jacob Drapekin of Chicago, who was making the trip to spend his last years in Palestine—died on the ship. After consultation with the Captain and Officers, Mr. Drapekin's last request was granted—to be buried in the Holy Land, and on Tuesday, March 31st, with his coffin draped in the American flag—it was placed on deck. The last rites were performed in Hebrew and English by Rabbi Ashinsky. The Captain also said a few words.” Finally I had some facts: not many, but enough to know my family's story had at least a grain of truth. In 2009, about to leave for Israel for my fourth visit, I consulted the JewishGen Online Worldwide Burial Registry (JOWBR) where I found “Jewish Names in Selected U.S. State Department Files (RG59),” including a search engine for a database assembled by volunteers from the Jewish Genealogical Society of Greater Washington. “Drapekin” produced no results, but “Drapkin” yielded: DRAPKIN, Jacob Haifa Palestine Box #4580, File 367, Document n.113 A week later I was at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, holding “Report of the Death of an American Citizen”: one “Jacob Drapkin,” from Chicago, of “chronic endocarditis and myocarditis.” Included with the six sheets is a list of the property in his possession: a $10,000 letter of credit, “one watch and chain with knife,” $1,435 in cash and “American Express cheques,” one sealed bundle, one sealed valise, and one locked trunk—all witnessed by a second-class passenger. And another fact: his body was buried in "The Jewish Cemetery, Haifa, Palestine."

Within hours after emailing Hanna Steinblatt, the president of the Haifa branch of the Israel Genealogical Society, she confirmed that the cemetery I’d visited in 1977 was the only one in use until 1934. She included the phone number of the chevra kadisha to contact for more information. And so, in a drought-ending downpour in the spring of 2009, my husband and I waded through wet, waist-high brambles and weeds seeking grave 17 in row 6. There were no rows, no sections, so my husband called the chevra kadisha again. He read to the man who answered the names on the stones nearby. “Walk to your left.” More names. “Walk toward the Mediterranean.” More names. “Go back to your right.” Between Yosef Halutz (grave 16) and Yaakov Kretzman (grave 18) in the packed cemetery, there was the space of one grave with no marker: Jacob Drapekin’s. We couldn’t leave a stone, but we did say prayers. Back home, I returned to the Internet. In 1925, under the new ownership of the American Palestine Line, incorporated by a Zionist New York judge, the President Arthur was fitted out as the first ship in 2,000 years to fly “the flag of Judea,” and begin a new steamship service “linking Palestine with New York.” The departure on March 12, 1925, was described at length in the New York Times. “About 5,000” people gathered at West Houston Street to see the “500 prominent American Jews” off, and a ceremony included the Star-Spangled Banner, Hatikvah, and speeches by leading New York rabbis. A follow-up article on April 2, 1925, described the landing in Haifa and noted that after having difficulty alighting because of the crowds welcoming the ship in Haifa, “the American tourists departed immediately for Jerusalem to be present at the official opening of the Hebrew University on Mount Scopus, which takes place today.” While there is no mention of my great-grandfather’s funeral in the Times, there was on Wikipedia. It was missing his name, so I added it. In 2010, the Israeli Knesset Minister of Religious Services Yaakov Margi complained about the condition of the cemetery in Haifa. Hanna Steinblatt reported to me that an agreement was reached: the cemetery will be maintained by the municipality and the Ministry will “make paths and reconstruct the place.” Friends ask if I’ll put up a stone. I’ve looked into it, but publishing his story—and that of the President Arthur, which I have recently written—may be an even more lasting matzevah (marker) for Jacob Drapekin: A second-class passenger whose funeral was attended by 500 prominent Jews and reported around the world, thanks to a sympathetic sea captain, a first-class passenger who wrote about it, his great-grandson who put the account on the Internet 80 years later, and volunteers who believe that facts matter. Thank you, JewishGen. March 2012

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||