|

|

|

[Page 249]

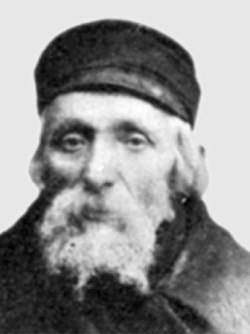

Mordechaj Iglewicz

|

Reb Mordechaj Iglewicz was born in 1865 in Nowogrod (near Lomza), but he was known in Ostrolenka as Mordechaj Farber (the Dyer). The name was given to him because he operated a dye-works. Who did not know him in our city? He settled in Ostrolenka after he left the Yeshiva of Wolozin. All his life, he aspired to Torah and work. He always mentioned the saying of our Sages, that “Torah without work – its end is idleness”. Therefore, he gathered all Ostrolenka's workmen and taught them Torah. He adapted himself to them. For whoever was available only early in the morning – he held a lesson early in the morning. Whoever finished his work in the evening, studied with him in the evening, as well as before evening, etc. The most important thing – study and work, combined with each other, and equally important.

Thanks to his initiative, Torah scholars grew in Ostrolenka. Reb Mordechaj Iglewicz did not only study with his students. He also cared about them and was always ready to help in anything they asked. If he was unable to help, he encouraged others to help, and no one dared refuse him. Although Reb Mordechaj worked hard until his last day, he did not spend a minute without the study of Torah. Even when he sat in his workshop next to a vat of boiling dye, he stirred the vat with one hand, and held a Gemara and learned with the other. To us, too, his grandsons, he always explained everything with love and simplicity.

I remember an incident when I was at my grandfather's, and no one else was home except us two. Grandfather, as usual, worked and learned at the same time.

Then a beggar entered and asked for a donation. I was very small and replied that no one was home, because I did not want to disturb Grandfather at his work and his studies. But my grandfather had good hearing and heard my answer. He immediately entered the room and ordered me to run after the beggar and give him a donation. Later, he began to lecture me, in these words: “My child, when a poor person asks for a donation, it is forbidden to refuse him. This is a sign that he is needy and apparently hungry for bread. How could you say that no one was home, when I was in the workshop next door?” I tried to justify myself, maintaining that I did not have the courage to disturb him, and he answered: “You should have given the man a piece of bread or a little sugar or something else yourself – you should help people!”

Grandfather protected Judaism. I remember that once missionaries came to Ostrolenka. He stopped his work and went outside immediately. What he did there, I don't know. I only saw how he gathered all the papers that they strewed in the street, and also grabbed sheets from people's hands – so that the children would not read and be influenced, Heaven forbid, by what was written there. On that day, he was really broken. “They have the insolence to come here and to desire to influence our children”, he complained.

I have only these few memories of my grandfather, because I was very young then and did not understand many things. But especially etched in my memory are Grandfather's last days. When he sensed his departure from the world drawing near, he called me to him, because we lived next door and I was the only one at home then. (My sister, Chawa, was at work, and my brother, Ben Cyjon, was studying at the heder.) He sent me to buy strong drink and cakes, and then asked me to call Reb Josef Nasielski. When the latter stood by his bed, he said to him: “You see that I am about to die. I will not find rest if my students are without a teacher. I

[Page 250]

ask that you continue to learn with them, that you will be their teacher.” Just then, he did not have another candidate to replace him. He drank a toast with him and wished him success. They parted, and after two days, Grandfather passed away (it was on Chanukah 1927). The study group did not last long, and, at any event, the lessons with the students stopped, and they were left like “sheep without a shepherd”. Josef Nasielski, of blessed memory was a weak man, unable to devote himself to them. The students used to gather on my grandfather's yahrzeit. Some of them are in Israel today, and there, too, they observed his yahrzeit for a long time.

May the memory of the righteous be a blessing.

|

There are in the world modest people who run from honor and do not want to bend their will to anyone. They are “shorter than grass and stiller than water”, and this is precisely what draws the attention of others. They arouse respect for their rich inner feelings and their lofty attributes. Such a one was Reb Naftali-Cwi Iwri, of blessed memory.

When I first saw him, with my childish instincts, I sensed that he was different from others. And I was not disappointed. Learned, his face expressed the fear of Heaven and respect for others. His eyes were always lowered with sincere modesty; when he raised his brows, I saw eyes that expressed good-heartedness and love for mankind.

On a certain morning, I saw him sitting in the shtebl, wrapped in a prayer shawl and phylacteries, learning with devotion. His appearance was not that of a man from the world of law. In this Jew – I thought – was stamped the spark of Reb Zysza Anipoler, the righteous of blessed memory.

Respect to his memory.

|

He was a Torah scholar, with a deep feeling for the Land of Israel. He had seven children and lived in great penury, despite the fact that he had several sources of livelihood: a bakery and a small delicatessen; he worked at the municipal bath house and was also a “part-time” carter, in partnership with the horse and wagon of Lejbel the Engraver. It was said that Reb Szmuel Baruch sometimes stumbled when he traveled with his wagon in the streets of the city, because he was a Godfearing Jew, occupied with the practice of his religion. It also happened that once he drove his wagon straight … into the house of Lejbel the Engraver.

Reb Szmuel Baruch had a warm heart and soul. Despite his poverty, he was ready to give others whatever he had, and all his deeds were for the sake of Heaven. If he heard that there was a Jew somewhere who was hungry for bread, he immediately came to his aid and organized a collection among good Jews to help the needy. He also succeeded in obtaining a respectable sum as charity from a rich Jew, without an exact date for the return of the loan … He also collected money in the city to pay the tuition of poor students who learned in a heder. He was prominently involved in every charitable deed in the city.

He was the type of Chassidic Jew in whom Torah and good deeds were combined; nevertheless, he was strict about religion. When his son, Lejbel Landau, a member of the Rightist Poalei Zion began to study carpentry – this was a sin in his father's eyes, a desecration of the Jewish way of life. He sat shiva in

[Page 251]

the shtebl of the Gur Chassidim, and cried for his bitter fate … But after his son learned baking, his attitude changed. Reb Szmuel Baruch already consented to this, because during work, while the dough was rising, it was possible to learn a page of Gemara …

Indeed, Lejbel Landau was chosen later as the representative of the bakers in the professional union of Ostrolenka, which did not exist much longer because of provocation.

When World War II broke out, Reb Szmuel Baruch wandered deep into Russia and passed away there. His wife, Leja, emigrated to Israel after the war, to her sons and daughters, who came there years before, and there she passed away.

May their memories be blessed.

Moshe Kamin, Netanya

He was called Awraham Giszes (Gisze's) – after his wife. He was a Jew with a sensitive heart, a Gur Chassid and a respectable merchant (the owner of a food store). He was hardly involved in business matters; most of the time his wife, Gisze, was in the store. He learned day and night and distributed donations generously.

I remember that on one Passover Eve, a meeting of public figures and regular balabatim was held, concerning the urgent need to help the poor. The most pressing question was: from whom to ask, to whom to turn? Quietly, from the side, Awraham Giszes declared: “ We will divide the public into two parts: he who is not included among those who receive – he will be among those who give …”

These words, which were not said by a professional community worker, but by a modest, simple man, made a great impression on all those present and influenced them. As stated, he was ready to help any Jew in time of trouble.

In 1939, exactly at the outbreak of World War II, Awraham passed away in Shiadowa, a town “on the Russian side”. His wife and the rest of the family members were murdered by the Nazis, may their names be erased. There remains only one daughter in Israel (Golda, the wife of Josef Wonszak).

Honor to his memory.

One of the most fanatic Chassidim in the shtebl of the Gur Chassidim. His wife was the breadwinner. He was very angry at her, when, on a market day, her labor pains suddenly began, and he himself had to stand in the store and sell merchandise. “Look,” he said, “she couldn't wait until evening, an act of the devil. Because of her, I can't go to the shtebl today …”

When his son, Szymon, went to America, he rent his clothes [a sign of mourning] for him and refused to write him letters. One evening, after some years, the door of Reb Ben Cyjon's home opened. On the threshold stood a man in “German” dress, clean-shaven, a derby on his head. This was his son, the young American “trinket” … At first, a smile appeared on the father's face. One would have thought that his paternal feelings would overcome his religious fanaticism – but as he spoke, his countenance became grave. He turned his back on his son, and did not want to see him …

But the dramatic moment had a comic ending. When his son fell asleep, the father went over to his bed, waved his tzitzit [fringes on the corners of a ritual garment] over his head and muttered: “Evil Inclination, Evil Inclination, leave my son!” The son awoke and when he saw this performance, grabbed the tzitzit from his father's hand and responded in kind: “Stubborn One! Obstinate One! Leave my father!”

In his poem, My Father, Bialik describes a father who is happy and contented when he is in the study hall. On the other hand, the hours he has to spend in the pub with his unpleasant customers are a heavy burden for him. But, even then, he has some consolation: from time to time he glances at a holy book …

Reb Awraham Lazer Skrobacz was a type like this, a holy and pure Jew. He had a housewares store and, in one of its corners, he sold Polish textbooks. It is said that Jews are sometimes permitted, between day and night, to peer into these books … Usually, however, an

[Page 252]

open Gemara rested on his table. It apparently interested him more than the customers … Nevertheless, [his] Polish customers never paid more for the same product than the Jews did – everyone had complete confidence in him. Such was the character of Reb Awraham Lazer, a small merchant, a gentle man.

In the city, they called him “The Lottery Conductor”. He held private lotteries at home for prayer books, Gemaras or any other item of value. He was a Gur Chassid and barely made a living. Once, on Yom Kippur Eve, I met him on the street and, uncharacteristically, he was very sad. “What has happened to you, Reb Welwel? Indeed, today it is a mitzvah to eat and drink!” I asked him. Instead of replying, his eyes filled with tears and he told me that the doctor had forbidden him to fast. “It is a mortal danger for me,” he said. He had therefore decided to ask a rabbi's opinion. To his disappointment, the rabbi also ruled: “Eat!” “A catastrophe such as this has never occurred since the creation of the world!” he said in a voice filled with pain. He did not take his serious illness into consideration even for a moment, for he was already used to it. But, Lord of the Universe, how can one eat on Yom Kippur? It was hard for him to reconcile himself to this.

At times like these, I thought of Reb Levi Yitzhak of Berditchev, who sought to defend the Jewish people. He would surely intercede for the defense of the Jews at a Torah law litigation with the Lord of the Universe. For example, Chaim Welwel Malach from Ostrolenka, ready to sacrifice his physical existence for a mitzvah, who suffered because he could not observe it, although the holy Torah released him from this duty …

Zawel the Tailor

I became acquainted with him when I was still a small child. A folk type, with a long, flowing beard, he sat near his tailor's workshop with a large velvet skullcap on his head. While working, he sang to himself cantorial selections that he had heard in the study hall on Sabbaths or High Holy Days. Like everyone in those days, he worked from morning until the late hours of the night. The only respite was for afternoon-evening prayers. Then, he joined the company at the long table and heard words of Torah from Mordechaj Farber (the painter), who served as their rabbi. He did not get involved in public matters. “Community leaders, public representatives,” he said, “must be rich and respectable merchants, not workmen.”

He always made the garments he sewed wider than necessary. First, he explained, something wide can always be made smaller. Second, clothes are used for many years and, with time, a person gets fatter … He lived in one room, which served him simultaneously as a workshop, a guest room and a bedroom …

The Fruit SellerI never knew and never heard his name. It may be that, in time, he forgot his own name. The city invented a nickname for him, suiting his work as a fruit seller in the market. One day, a competitor opened a stand near his own and stole all his customers. Despondent, he went to the study hall and took comfort in reading the Psalms, skipping not only individual words, but whole verses …

“ What do you wish for your competitor in your heart?” I asked him. “It is forbidden to curse a Jew. Apparently, he deserves it,” was his answer.

“ If an angel came from heaven now, ready to fulfill all your wishes, what would you request?” I persisted. “ Bread to repletion and clothes for my body,” he answered briefly.

Thus was the Bontshe the Silent of Ostrolenka – although he had a broken heart, he did not harbor hatred.

The “Dead” ShoemakerWhy they called him this, I don't know. It may be because he was overly industriousness at work. I always wondered why the hammer did not fall from his hand. In the street, it was hard to tell if he was walking or standing. One evening, to my great amazement, I saw him running quickly. “What has happened?” I asked. “I am afraid of being late for afternoon prayers,” he said and immediately disappeared.

Then I understood the words of Our Sages: “Be strong as the leopard …”

The Way to Mendel Bialy's Sawmill

As in every city, Ostrolenka, too, was divided into neighborhoods. Each had its own unique appearance; its residents had their own singularity.

I will begin with a description of the road leading to Bialy's sawmill. On one side were fields that were plowed, sown and turning green, belonging to Christian owners – Pozniewski, Wojciechowski, Olszewski and others, whose relations with the Jewish population of Ostrolenka were good. On the other side was the Narew River, which, according to the seasons of the year, sometimes flowed quietly, sometimes was stormy and wild, and sometimes overflowed its banks and flooded the road. In certain places, Christian workers pulled from the river rafts that had arrived on it.

The sawmill stood on a giant plot on a hill far from the river. Sawn boards of different sizes were always piled it. Its customers were city dwellers and rurals alike. At one end of the plot stood a beautiful wooden house and, around it, a cultivated flower garden. The owner of the sawmill, Reb Mendel Bialy, and the accountant, Reb Szmuelke Frydman, lived there.

Mendel Bialy was a friend of my father, of blessed memory. I often visited his house because of my work for Keren HaYesod. He was the Chairman of this Zionist institution. Mendel Bialy remains in my memory as one of the most respected personages of our city: a very elegant man, known for his good relations with young and old alike. He was therefore accepted by all strata of the population, Jewish and Christian. Beyond the sawmill sprawled the new market, but there was a big difference between its right and left sides. On the left side lived merchants and shopkeepers: the family of Mosze Aron Edel, who owned storehouses for wood, Grandmother Gita, who owned a textile products store, and others.

Grandmother Gitel was blessed with many children and grandchildren, who were among the notables of the city, both economically and socially. She was a proud, wise and vigorous woman, conscious of her important contribution to the city. In short, “a woman with a headdress”, that is, “a woman of iron”. Her grandson, Hercke Sojka, of blessed memory, said that stuck into the headdress on her head was a pin with a big “head”. When a customer would bargain and ask, “Gita, can I get the material cheaper?” (and here came the proposed price) – she grasped the “head” of the pin and swore on it: “May my “head” live like this, I paid this price in Warsaw!”

The New Market – the Right SideButchers and horse traders lived on the right side of the market. One horse trader, called Fajczarz (someone with a pipe), had giant pipe that held a whole package of tobacco and had a metal cover. From after Havdala on Motzei Shabbat until candle lighting on Friday, he did not take it out of his mouth.

Near him lived Icze Meir, who owned a carriage in which he transported passengers to the Kaczyny railway station. He wore a wide belt, a cloth waistcoat and, around his neck, a chain of white metal, to which were attached miniature items: a few horseshoes, a horse's head, a rifle, a compass and some other tiny things which he wore with pride. When he was asked, “Icze Meir, what is that?” (and there were many who asked), he would take the chain out slowly and importantly, until a round silver box with a “head” popped out of his waistcoat pocket. This was a watch with two covers. On them were engraved the heads of kings and Russian dignitaries and the inscription “A gift to a sharpshooter”. He used to read the few words very slowly and then translate them from Russian to Yiddish.

He sat on his seat facing the passengers instead of the horse, thereby observing the impression his stories made on them. The passengers, seeing the train suddenly approaching, cried “Icze Meir, faster, we will miss the train!” Only then did he take the “famous instrument” out of his waistcoat pocket and announce like a proclamation: “The train may be early, but my watch is accurate!” On this watch's conscience weighed more than one passenger who missed a train he meant to take …

And here is Reb Jehuda Nadborny, a broad man, with his even broader wife (I have forgotten her name).

[Page 254]

A man rich in money and children. He had his own home and a large butcher shop with a number of barns. I remember this family, and I want to relate something about them, about one of the daughters. As I said, this family was known for its many offspring. And thus, in the chain of births, triplets were born – one son and two daughters. A daughter of the triplets appeared one fine day, stepping along the bridge and leading a large ox, a rope tied to its horns. The ox followed her without any resistance. In the face of this spectacle, the Christians crossed themselves and the Jews expressed their wishes that she reach home safely. Passersby looked on in wonder at this strange parade.

Near all these lived the carter, Czaplipaj, who caught on to the idea of going to Israel. Since he did not have the means to do so, he contrived a plan: he would leave in a carriage hitched to his horse and, in every city on the way, he would stay for a few days, work there and earn enough to continue on his way. He did not have children and his wife agreed to his plan.

One day he approached me, very indignant, and told me that he had just spoken to Szafran's son, who had just returned from Israel (he referred to Jechiel, of blessed memory), and it turned out that his plan was not viable for a number of reasons. First of all, Israel was very far; second, one must cross an ocean. In general, he was ashamed to talk about it with his comrades, who held that the idea of traveling to Israel was meant only for well-to-do youths. He wondered why those with the blue ties (that is, HaShomer HaTzair) and the others with the blue and white flag (the Zionists) – who were able to go, why were they still living here among the Gentiles? He opened his deepest thoughts to me and spoke with love and yearning of something far and unattainable, using expressions which were simple, but sincere and true. Tears glittered in his eyes. I felt guilty before him. No Zionist leader, with a passionate speech replete with slogans, could influence more than this carter, a simple, honest man, with his sincere words.

When, after a time, I saw the play The Travels of Benjamin III staged in Israel (the role of Benjamin was played by my brother, the famous Israeli actor, Meir Margalit), and heard Benjamin's plan – how he, and with him Senderl, “The Woman”, wanted to get to Israel – “the Benjamin” of our Ostrolenka immediately sprang to my memory.

As I said, all these lived on the right side of the new market. Behind their houses was an empty space, where their animals and wagons were kept. Here, too, dovecotes were built. Youths attended to them, bringing them both pleasure and income.

Raising doves was a profitable business, and Jews and Christians alike engaged in it. Many of the well-todo were carried away by this occupation. They came here and brought a pair of purebred doves or carrier pigeons. Since there was no suitable place to keep them at their homes, they left them with the seller and paid for the cost of their food. In exchange, they were allowed to come before evening, to release the doves and make sure that they returned to the dovecote, and did not fall into the hands of strangers. It happened, too, that the doves did not return and new ones had to be purchased.

Near the dovecotes and the barns lived a family called “Krejer”. I cannot remember their other name. He owned an inactive tin smithy. There were a few sons and even more daughters. I am not sure if all the boys were theirs. One of the family members was an amateur fiddler. For years, he ran with the fiddle under his arm to Christian teachers and, later on, to Lejbel Frydman, for music lessons. Afterwards, he already played at weddings and celebrations.

In another corner of this neighborhood, in a small shack, lived a former carter, called Kacze Berel. He was thin and shriveled up beyond his years. No one knew how many wives he had had (divorced and dead), and he himself did not remember … Once the old man passed the market square and saw a crowd of people. To his question, “What is happening here? Where is everyone running?” someone yelled in his ear: “Grandfather, a young couple is being wed.” In reply, he groaned and said “Oy vey, they still want to marry!”

In Benedon's “Kingdom”At the continuation of Goworowo Street sprawled “Benedon's region”. The place was so-called because Reb Welwel Benedon built barracks for the Russian army there. After World War I, when the city of Ostrolenka was almost completely burned, only Benedon's barracks and a few other structures remained. The city's inhabitants who returned and could not find a roof over their heads, settled in these barracks, which were renovated and turned into private apartments. The large halls were turned into rooms and kitchens were added to them. Bathrooms were not yet in style. The municipal ritual bath and the bath house served this need of the population.

[Page 255]

Most of the Jewish population was concentrated in these buildings, and its composition was quite varied. Merchants, among them the most well-to-do, took the front, facing the pig market. Stores were built there, adjacent to the apartments. In the inner courtyard, similar to a closed crate, workshops were built. There was no occupation that was not represented, from Josel the Carpenter (who would begin to make a clothes closet and it came out a noodle board …) to a coppersmith, who made unbelievably beautiful items.

Besides the merchants and workmen, religious workers also lived there, such as Naftali the Ritual Slaughterer, Mendel Lomzer the Melamed, Mendel Richter the Gabbai, and even the bath attendant and the [ritual bath] “immerser” for women's purity. In short: an autonomous city in and of itself.

When Reb Welwel Benedon passed away at a ripe old age, management of his business passed to his wife and his children who had not yet married: Szlomo, Eliezer (Lolek), Chana and Chaim, who were my friends. The industrious one among them was Eliezer, a good and gentle fellow, who loved to use high-flown and pathetic expressions. For example, when he was looking for keys, he would say, “God of the Keys, tell me, where are my keys?” In similar circumstances, he scattered words of beauty, which had nothing to do with anything. The janitor of the courtyard assisted him in cultivating his greatness. The sewage there accumulated in pits which were emptied of their contents using a barrel harnessed to a horse. When Jozef the Janitor filled the barrel and began to drive, Eliezer's voice was suddenly heard: “Jozef, stop!” He went over the barrel, peeked into it and cried in a dramatic voice: “Jozef, you are making me miserable! The barrel is not full!” People used to make jokes about him, especially his younger brother, Chaim, but this did not prevent him from continuing in his characteristic behavior.

One of Benedon's tenants was Reb Symcha Szlomkes, a righteous Chassidic Jew of average height, with a thick beard and earlocks. He always wore a heavy, shiny, musty kapote and leather boots which he rubbed with fish oil, in honor of the Sabbath. Reb Symcha ran food, grain, paint, oil and kerosene businesses, and samples of all these products were reflected on his clothes and his beard. Sometimes, when a customer forgot what he wanted to buy, it was enough for him to look at Symcha or smell his clothes, and he immediately remembered what he wanted. He himself was the best display window for his wares.

Reb Symcha was also the owner of a three-story building on Ostrowa Street, but the house was too large for him to live in. He felt better in Benedon's housing than in his own apartment, which was adjacent to his business.

Miracles and wonders were told of his bed, which he brought from an estate owner's manor. His sheets and pillows were always packed in a bundle. “Reb Symcha, what is the bundle for?” people asked him. “What do you think? I'll wait for a fire to break out to begin packing?” was his short, sweet answer.

Speaking of Benedon's “kingdom”, I cannot omit the spectacles that took place there before Passover. Anyone who has not seen them does not know what preparations for Passover mean. Immediately after Purim, when the snow was melting and the streets were full of mud up to our necks, Mojszele the Whitewasher appeared. A short man, hunch-backed, with a beard that apparently once grew, but regretted it and stopped growing … His voice was high, like a woman's. A sport-joker once asked him in fun: “Reb Mosze, can't you speak more deeply (grub in Yiddish, also crude)?” “Yes”, he replied, “Why not? Kiss my rear end … If you wish, I can be even cruder!”

In one hand, he carried a bucket of paint and, in the second, a brush affixed to a long stick. Mojszele's appearance in “Benedon's Kingdom” on the days before Passover was like a rallying call to the battle field … Women thronged to him from everywhere, like – lehavdil! [but different!] – a Rebbe's Chassidim. Each one began to beg him coquettishly and wanted to be his first customer. Mojszele, on his part, full of selfconfidence and aware of his own value, surrounded by so many women, answered: First, already last year, he had promised one of them that this year, she would be the first. And second, there is a new and uniform kind of paint this year, which covers old paint well. When he saw that the women “bought” this, he immediately pulled out a new card: “Know that I do not intend to paint the finishing trim. I don't have time for such nonsense …” In response to their dissatisfaction, he declared, “Whoever agrees – good, and whoever doesn't want – doesn't have to!” With no other alternative, they accepted his offer.

The minute Mojszele began his work, furniture of all kinds and styles was piled in all the courtyards. Everyone began to wash, to polish, to rub and pour water … Papers, feathers and straw flew in the air – it was merry! The main thing was the women's wardrobes.

[Page 256]

Each wanted to compete with her neighbor's clothes and shoes. If one wore her husband's shoes, then the other wore her husband's boots. Their heads were bound with all sorts of strange, colorful kerchiefs. There was really a competition of wide, long, colorful dresses. Each wanted to beat the other, as if to prove importance or strength.

The “final battle” took place when implements were made kosher [for Passover]. At every corner of the city, bonfires burned, and on them giant pots of boiling water and white-hot stones for koshering implements [that had been used for] leavened food. Although there was an accepted price for koshering every implement, they could not help but bargain: “What's so terrible? I paid for four pots, so I can kosher a few more spoons and small utensils without paying more”, they said. Because of the rush, the “kosherers” accepted every offer.

Seder nights were celebrated with joy, spotlessness and kashrut [fitness according to Jewish dietary laws]. From bitter herbs and charoset (a mixture eaten on Passover) to matzo balls and the Four Cups, everything was on the tables at the homes of the rich and poor alike. The community took care that no Jewish home lacked for anything.

When the “kings” sat at the table and conducted a proper Seder, their “queens” beamed with joy. They had, as our grandmothers used to say, “The grace of Leah and the beauty of Rachel”. Their festive garb emphasized all the more the contrast between a holiday and a weekday.

Kilinski StreetBehind “Benedon's region” began Kilinskiego Street (called Synagogue Street by the Jews), at the end of which lived Judel the Baker. After World War I, the street was widened and new two- or three-story buildings added, with porches and big, beautiful stores. The deserted, burned municipal synagogue remained as a “remembrance of the destruction”. Only its walls of bricks and mortar remained, and the low pillars with chains, which served as a fence for the synagogue. All the wooden parts were completely burned. The arched opening of the burned doors cast dread and fear on all passersby, old and young alike, especially at night. Everyone felt that an injustice was done to the synagogue by leaving it in its wretchedness. Our house stood opposite, so that more than the others, I felt the insult and the shame. When the community elders began to build the new study hall, I asked my father, who was one of them, “Why are you building a new study hall and not renovating the ruined synagogue?” He explained that an extensive population prayed in the study hall, while in the synagogue – only those of higher status.

The builders of the study hall were Aron Takson, the tailor, and his sons, who later built homes in Israel.

Many Ostrolenkans were among those who built the Land of Israel. Some of its students were building contractors in Israel.

The construction of the study hall roof was complicated. It was installed by Reb Tuwja the Builder (Wylozny), with the help of his sons, Mosze and Izrael. They were superb professionals. With wonder, we watched them “stride around” on the high roof, quickly and with self-confidence. Reb Tuwja and his sons emigrated to Israel, but did not continue working in their profession there. Some worked in the wood industry, others in metal. Reb Tuwja and his son, Izrael, as well as Reb Awraham Takson and his son, Mosze (Pesia Lachowicz's husband), passed away in Israel.

In the street, you always met almost the same faces. In the winter, Neszke Mejrann (Lachowicz) always wore a masculine short sheepskin fur, and was always rushing, busy with business. Sometimes, she took a rest from her business and began collecting donations for charity – for a respectable person who had met with distress. No one dared refuse her and, thus, she saved someone from an embarrassing situation.

Reb Fajwel-Lejb Herc, a tall man who wore a long kapote, worked in medicine, something between a doctor and a medic. He treated only men. When he was called to a patient, he entered the house like a tempest and asked: “Where is he?” His patients did not have time to lie in bed. They suffered mostly from severe colds, prickling in the back or constipation. He would place his ear on his patients' bodies, over their clothes, order them to breathe, to cough, and immediately determined the treatment: to do cupping, to smear on French turpentine – and that was that. He asked patients suffering from constipation to stick out their tongues. If the tongue was as white as milk, he would wipe it quickly with his hand and cry with satisfaction: “That's that!” – that is, he had removed the disease with his own hands. In addition, he ordered the patient to have an enema, to swallow caster oil and to drink sour milk.

At burial society dinners, I saw my neighbors, Noske Tejtelbojm, Szlomo Jabek, Herszel Szperling and

[Page 257]

Chackel Zylbersztejn. I was then still of an age where Father would take me with him. Besides them, dozens came to the dinners, headed by Chaim Berel the Slaughterer, a well-built man with a dark face and lively eyes, who led the additional Sabbath morning prayer in the large study hall. At the dinner, he set the tone. He sang and amused those gathered with words of Torah and wise Chassidic sayings. The crowd was tipsy. The more bottles emptied and the more portions eaten – the louder the singing became. Diets were not in style then. This occasion served them as a theater, a concert – lehavdil! – as a substitute for the other amusements of the “free” youths. Therefore, joy was great and expressed immense enthusiasm.

The Old Market (3rd May Square)The closer you came to the old market, the bigger and nicer the stores were. We did not have independent female shopkeepers, except for the few women whose devout husbands sat day and night and learned Torah, or widows. For the most part, women worked in business together with their husbands. I mostly remember the women from the iron stores: the wife of Chaim Szymon, Sara Dwora Zylbersztejn, Etka Thylim – cold, serious women, with a severe expression and a penetrating look. They never smiled. Although there were porches at their homes, on summer evenings, they liked to sit near their stores and follow the youths who went out to stroll in the direction of the bridge or the municipal park with a critical look. The clever mother of my friend, Awrejmel Frydman, used to “toss” an old Yiddish saying their way: “Vehr es hut kinder in de vegen – zul lazen leiten tzufreiden!” (He who has children in cradles – should let people be!)

Our city was blessed with straight, beautiful streets and well-trimmed trees on both sides of the pavement. The old market made a special impression, not to mention the bridge over the River Narew, which led to the “forts”. An abundance of greenery covered the mountain and the valley, and a large statue of General Bem, erected there, added importance.

In the afternoon hours, the strolls began. Every hour had its strollers. Among the first – the city's Rabbi, Rabbi Icchak Bursztejn, a Jew of dignified aspect, dressed in black rabbinic garb, clean and well-groomed. The handle of his walking stick was made of ivory, his appearance aroused respect among all the passersby. The Gentiles, as well, greeted him and made way for him. He used to stroll accompanied by the city's Dayan, Rabbi Jermiah, Chaim Berel the Ritual Slaughterer and the gabbai, Mendel Richter. During those hours, Reb Izrael Chmiel, my father, Aron Jakow Margaliot and Mosze Aron Kaczor also strolled. Mendel Gedanken, Efraim Chmiel, Zyskind Zusman and Szymon Czapnikiewicz walked in a separate group. When they all returned for afternoon-evening prayers, the youths began to gather at the corner of Ostrowa and Lomza Streets. Only the young men met at this corner. In the late evening hours, they looked for someone about who to joke and amuse themselves.

The people of our city had a healthy, natural, special and independent sense of humor. Sometimes, it was intentional and, sometimes, in all innocence. Near the municipality, at the home of Reb Mosze Szafran, his son, Jankel, opened a coffee house. At one o'clock in the morning, Reb Mosze would get up early to go to the ritual bath. When he saw through the shutter the group that sat there, playing cards, he said, “They feel like getting up so early to play cards! …”

Another story: two friends, in Chassidic dress, Reb Pinie Gedanken and Dan Kachan, strolled the streets of Ostrolenka every day. They had deserted their business long ago. Their entire “business” was mischief, spreading fine words and proverbs, and sitting in the municipal court to follow the proceedings. Often, a dispute broke out between them as to the justice of the verdict … When these two jesters appeared in Ostrolenka's neighborhoods – it was merry.

Pinie Gedanken was one of the subjects of juicy, unique humor and jests in our city. It is said that once, when Pinie went to Warsaw and arrived at the Kaczyny railway station early in the morning, he met a couple strolling. He went over to them, apologized politely and asked: “Would you be kind enough to tell me – are you still strolling here from yesterday – or from today?”

And so on and so forth …

For generations, Ostrolenka's neighborhoods absorbed vibrant Jewish lives and deep-rooted Yiddishkeit [Jewishness]. Today, the entire area has become Christian. The Jewish tragedy, however, stands out at every corner there …

Jewish life in Ostrolenka is no more.

[Page 258]

|

|

|

|

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Ostrołęka, Poland

Ostrołęka, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 25 Nov 2011 by LA