|

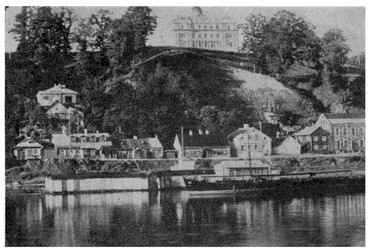

Aleksot and the bridge over the Neiman

|

|

[Page 1191]

Translated by Jerrold Landau

Donated by Art Poskanzer

|

|

Aleksot and the bridge over the Neiman |

I did not earn that merit because my father was a wealthy householder or a great scholar. My father was a simple hard-working Jew who had to seek a livelihood for his large eleven-person family every day. I had that merit because my father repaired the eruv[2] of Yatkever Street almost every week, which the gentiles had destroyed so that the Jews would not be able to carry their cholents [Sabbath stew] that they had left in the ovens of the bakeries on the Sabbath eve.

Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan, of holy blessed memory, simply regarded my father as a holy man due to that great mitzvah [good deed]. Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan would often stand on his balcony and watch my father climb atop the roofs to fasten the wires. The rabbi's lips would murmur that a misfortune should not, Heaven forbid, befall my father in his service to G-d and the Jewish people.

When I was six or seven years old, I

[Page 1192]

knew the old city of Kovno very well. I already knew the Jewish Yatkever Street, Jonaver Street, Bridge Street, Parade Place, Wilkomir Street, Yisrael Rabinovitch's Alley, Katz' Alley, Neviazke's Alley, the Neiman and Viliya Rivers, The Slobodker Bridge, Aleksoter Bridge, and the Beis Midrashes [Hebrew high schools] of the old city. Higher up, starting from the alley behind the civic garden (Gorodskaj Sad), was the Sobor, the Comendator, and Tilman's and Rekas' factories (where, incidentally, they used to work on the Sabbath). During that time, for me, all of those places were a very far walk into a strange non-Jewish world. A six or seven year old boy would not have been allowed to leave his home without his father's knowledge. If one would have asked one's father, the response would have been -- study the Torah portion better so that you will have more of the World To Come, rather than crawling to the gentiles.

I do not know if there were many gentiles in Kovno at that time. I had only heard about them from my father. There were almost no gentiles in the Old City except for the janitor of the courtyard and Janek the Drunk, who took care of the lights in the Butcher's Kloiz[3] on the Sabbath. True gentiles who would mingle with Jews -- such I did not see.

[Page 1193]

To the limited extent that I knew Kovno during that time, the city seemed to me to be the largest city in the world. The factories of Chatzkel Joffe, Simcha Aronovitch, Zalkin Eliashe (the father of the “Baal Machshoves”[4]) Rabinovitch's iron shop, Leizer Eplniks, Riva Gutla the dairywomen, Shmuel the midwife's[5], and others -- such stores seemed like large enterprises. Of course, there were also small shops and booths in the fish market, potato market, and the surrounding alleyways. However, according to my conception, these were poor shops, despite the fact that the owners of the larger shops were also not great wealthy people, as I later came to realize. Such householders, who would come to the Butcher's Kloiz on Sabbaths and festivals wearing top hats, left the impression upon me as being very wealthy individuals.

|

|

Vilner Street |

The extent that poverty pervaded in the majority of the Jewish homes can be illustrated by the following joke. Once, a Jew wanted some sour cream on Saturday night after Havdallah[6]. He said to one of his daughters:

[Page 1194]

“Go to Riva Gutla's dairy store, ask for a groszy worth of sour cream, and give her a pot full of a good week, but no money.” Another Jew asks his wife to go to Leah the herring seller to purchase a bit of herring-“lok,” and she purchased herring for a kopeck the next day.

In the region, that march of the donation collectors provoked blood and protest in many homes. The poor people who went to collect with their wives were happy when a shopkeeper would recognize somebody's wife and would refuse to also give the wife a half groszy.

Once, I had the opportunity to see how a wife of one such poor person who had already received his half groszy fought with the shopkeeper, claiming that he should also give her a donation. She told him that her husband agreed to marry her because she said that she would also collect donations. If she does not bring in as much as he does, her husband may, Heaven forbid, regret the match. She wept to the shopkeeper to have mercy on her young life.

The Beis Midrashes and various shtibels were packed at shacharit, mincha and maariv[7]. Jews were careful not to miss a kedusha. Shopkeepers would shut their stores and tradesman would close their workshops so that they could hurry to the kloiz to thank and praise G-d, and to snatch a mitzvah. This was not due to extra earnings or income. They would at least thank their Creator for the bit of health that He gives to His Jews. In truth, I did not know any Jewish shopkeeper or tradesman who did not have some sort of illness. Wealthy people would travel to heal themselves in Germany or Karlsbad. The poor people would borrow money from the Kovno charitable fund for a doctor, or for a bit of milk for a sick child.

The entire week was filled with worry and

[Page 1195]

poverty, but when the Sabbath or festival came, Jewish Kovno sparkled with pious holiness.

On Friday afternoon, the shopkeepers already began to lock their shops. One did not wait until the sun commanded the shopkeepers to close their shops. The street people with their little carriages, the tradesmen, the water carriers, the businessmen of the marketplace, and the regular Jews all went home to get dressed, wash up, and prepare to greet the Sabbath. On Friday night, it was as if the Divine Presence enveloped Kovno. Jews with combed beards filled the Beis Midrashes with prayer and melodies as if from heavenly angels coming before the Throne of Honor. It seemed that the Jews here had everything good, and did not know of any concerns about livelihood.

A mysterious calm came along with the Sabbath Day. Few Jews were seen outside during the day. Even a gentile did not go through the streets of Kovno on the Sabbath. The shops were locked, and the houses were closed. Cheder [religious elementary school] children who played with buttons in the synagogue yard all week comported themselves on the Sabbath in a quiet, stately manner out of awe. They did not raise their voices, as that would have disturbed the calm of their parents on the holy Sabbath.

On the Sabbath between mincha and maariv, Jews would go for a stroll along the Slobodker or Aleksoter bridges. It was a stroll with holy steps on the Aleksoter Bridge when Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan would walk with two rabbinical judges on both sides and respond “Good Sabbath, Good Year!” to the Jews who were passing by.

Those walks bring to mind a memory. My father and I would go for a stroll on the same bridge as did the Kovno Rabbi. When I would see Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan, I would let go of Father's hand, run to the rabbi, and wish him “Good Sabbath, Rabbi!” with great enthusiasm. Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan would respond to me “Good Sabbath! Good Year! You should be a pious Jew!”

My father derived a great deal of pleasure from this. Was it a small thing to receive such a blessing from the Kovno Rabbi?! Of course, his son would grow up to be a pious Jew. A blessing from such a Tzadik [a righteous man] must be fulfilled.

[Page 1196]

If a misfortune would take place in a small town, such as an evil decree, a fire, or a cholera outbreak, Kovno Jewry quickly set out to aid them. I recall that once at Passover time, the Kovno community was informed that a fire had broken out in Jonava. Jewish houses and property were burnt. However, even more so, people lamented that Passover would be spoiled because they could not save the matzos [unleavened bread] that the Jews had prepared for the festival.

I recall how Jews rolled up their sleeves, ran through the streets with haste and collected matzos, eggs, chicken fat, and wine for the four cups, loaded up the wagons and sent the Passover foods to the people of Jonava so that they would not have any transgression, and so that the festival would not be marred.

A second incident took place in the town of Wilki [Vilkija] during the wintertime. A cholera epidemic broke out there. First of all, people ran to the Beis Midrashes to supplicate that G-d should have mercy on the Jews of Wilki. Then the rabbi said that they should gather various powders, red and blue medicine, mustard, and medicinal herbs. Good, pious Jews were also called to take various sets of invalid tefillin [phylacteries] and tzitzis [ritual fringes] and burn them in the cemetery, so that Satan should not have any dominion over Jewish homes.

It is self-understood that the Jews of Kovno did everything that they were told. I myself was not certain that all the cures and amulets saved the Jews from cholera. However, the Jews of Kovno and Wilki were positive that the rabbi's prayers and pious recommendations indeed helped. Those who died nevertheless, died on account of a Heavenly decree. Were it not so, the prayers and amulets would have helped them.

Kovno was also a city of generosity to the emissaries who would come to collect for the Yeshivas, Torah scrolls, old age homes, Jewish hospitals, and other institutions. We have already mentioned the preachers and emissaries who used to come to Kovno to collect for the Land of Israel. Kovno treated all of the emissaries with great politeness, and never let them go on their way empty-handed.

The various institutions of social assistance played an important role for the poor classes of Kovno. These were institutions that used to help poor tradesmen, small businessmen, and ordinary poor people who were in need of help from the Jewish community.

My father was the leader of a few such organizations, such as “Gemilat Chesed” (charitable fund), “Hachnasat Kalla” (fund for poor brides), “Maos Chittin” (Fund for Passover provisions), “Talmud Torah,” “Malbish Arumim” (fund to provide clothing to the poor). He would designate me as the secretary to keep the books.

[Page 1197]

This was also due to the fact that my father had a poor mastery of writing and arithmetic. He would make his calculations in his head. His memory was indeed remarkable. Everything was remembered and calculated accurately, no worse than as if it was on paper.

Every Saturday night after the Sabbath, my father sat me down beside him to prepare the books, and he asked me to write. “Write down two kopecks for Leizer the bricklayer for the Talmud Torah society; or two kopecks for Malbish Arumim; this many kopecks for Maos Chittin. Leizer the water carrier settled 20 kopecks for his debt to Gemilat Chesed. Aryeh the tailor -- two rubles from Gemilat Chesed to repair his boots. Mote Tshvek was asked to register three kopecks for the Hachnasat Kalla society. Yankel, Feige's husband, did not yet pay the 50 kopecks for his debt on the week of the Torah portion of Vayikra”[8].

Thus did my father and certainly other trustees of the organizations conduct their bookkeeping on behalf of the Jewish people. I imagine that these organizations eased the situation for the beggars who did not want to beg from the community, pawn the lamps of their houses, or rely on a usurer who would take a high percent for a minuscule loan.

The Gemilat Chesed organization did not take any percentage of interest or any collateral. According to Jewish law, one is not allowed to take interest; and who would not trust a Jew, especially a poor one?

The fees that I earned to keep the books of all the organizations that my father directed were a pound of nuts for Passover. This did not come, Heaven forbid, from the money collected for the organizations. My father would give out of his own pocket so that I would have more desire to work for the benefit of the public. However, my fees were not only a pound of nuts. The shamash [a synagogue officer charged with keeping order during services] of the Kloiz of the Butchers used to give me the honor of standing with a plate near the kloiz on the eve of Yom Kippur [Day of Atonement] between Mincha and Maariv to collect groszy for clothing for the children of the Talmud Torah.

[Page 1198]

There were also societies for Shulchan Aruch (Code of Jewish Law), Ein Yaakov, and a group of clerks and tradesmen who would study the weekly Torah portion with a rabbi every Friday night. There was even a society of older cheder students who mastered the skill of learning chapters of Psalms by heart.

As I later learned, the organization of cheder youth was formed so that they would not have the inclination to run on Petrovka on summer Sabbaths to go swinging, or to have battles with sticks and stones on the frozen Neiman or Viliya in the winter. The teachers would indeed severely punish the youth who would skip coming to the kloiz on the Sabbath to be examined on the recital of Psalms. We young people believed with full faith that we would earn the World To Come. Indeed, how could one better serve the Master of the Universe than by learning all of the chapters of Psalms by heart?

I recall how Jews in the Butchers' Kloiz used to tell terrible stories about the “Tzitzilistn”[10] and regarded this as a new, terrible decree from Heaven that would be bad for Jews. We young people did not understand what exactly these “Tzitzilistn” are. However, people would very often tell stories and legends about the “Tzitzilistn”, which injected a terrible fear in the older Jews, as well as in us young children who became very curious to learn more about them due to these stories.

At all times, Jews were afraid of the police. If a gorodovoi[11] or the pristov came, Jews understood that something was about to happen. In general throughout the world, police would not pass by the butcher shop, the synagogue yard, or the Jewish stores. Jews thought that perhaps they were looking for somebody to make an “akt” or give a “poviestke” for not keeping the yard or the shop clean. Now, however, when one sees even a plain, simple storosz, one suspected that the highest natchalsvo was sent to look for the “Tzitzilistn”. So? Indeed, what if a storozh or a policeman swoops down on the

[Page 1199]

Jewish street? Is this not the best sign of the new decree that is called “Tzitzilistn”?!

The Jews of the Butchers' Kloiz became even more confused and frightened from the incident related by Avraham the Shamash. He said that during the first minyan that morning, he had heard from Zalman the Shochet that on the Sabbath they had “taken” the doctor, a teacher in the gymnasium, and the priest's brother and sent them away on a black carriage. Furthermore, the governor himself was going around the streets of Kovno with gendarmes and searching the houses. They were especially searching the Jews.

Confounded with fear, the Jews first had a word with the children. “Did you hear, children, what is going on in Kovno? You should not get involved with the 'Tzitzilistn', and you should not stand within their four ells! Do not talk to them.” They did not suffice themselves with that. They were given several fierce spankings so that they would remember and understand that which their fathers had warned them about.

Just like the adults, we, the children of the cheder and Psalms Society, told one another about the new phenomenon of the Socialists in Kovno. Naturally, those untrue stories captured our fantasies. Like children who did not have any concept of such political matters, we all exaggerated, which aroused an even greater curiosity.

I recall that I once proposed to the Psalms Society that we all become “Tzitzilistn.” This aroused all the youths of the society. How come their fathers had warned them with harsh words that we must avoid them and not mention their names, why had they received fierce spankings from their fathers, and so on?

They quickly informed my teacher, who then informed my father. My father took me to task for this sin. “Is it possible! How did you come to such a sin, from where did you hear this? It is nothing other than the evil inclination or some bad thing that has entered you.” My father decided to watch my every step! He watched whether I ran to cheder or went slowly. He checked whether I received the Psalms with enthusiasm, or whether I skipped over anything.

Father did not see any signs that I had become involved with the 'Tzitzilistn.” Nevertheless, he found a transgression with respect to the story books that I would borrow from the bookseller for a kopeck every Friday afternoon. These were books about robbers, princes, and magicians that I read not only for myself, but to the

[Page 1200]

entire family. Father greatly enjoyed these books. He would think about the heroes, wander with the magicians, and even shed a tear about the bitter fate that befell the unfortunate victim in the books.

However, suddenly Father said that I must throw the books away. “Who has ever heard that a Jewish lad who will soon become Bar Mitzvah reads books in jargon?[12] Yiddish books are for women to read. A lad of your age should study Gemara, Bible, a portion in Chumash [Pentateuch], or a chapter of Psalms. The jargon books will bring misfortune upon you. You will become blackened by the Yellow Prison.”

|

|

Policziske Street (Reb Hershel Neviazher's Street) |

That prophecy of my father was indeed fulfilled a few years later. In 1903, I was arrested in a demonstration at the Kovno City Theater (Gorodeskai). It was a protest demonstration against the pogroms and persecution of the Jews in Russia. Naturally, we spoke out against the Czarist regime and demanded political freedom, a shorter work week for the workers, and national rights for the people of Russia.

At every demonstration, more than 100 demonstrators were arrested and brought to the Kovno Yellow Prison. It is remarkable that many youths with whom I had studied in cheder, including some members of the Psalms Society, were among those arrested. Neither I nor the others realized that we would be joining the Bundist Organization, and that we would belong to the

[Page 1201]

Socialist Movement. I was very surprised when I found youths from wealthy homes, students of the Slobodka Yeshiva and even from the Mussar Shtibels among those arrested.

There were also married men and women among those arrested, as well as members of the intelligentsia and students of the gymnasiums. However, the largest group were workers of various trades.

I have no doubt that the exaggerated, mysterious stories and legend told by our fathers about the “Tzitzilistn” brought their good, pious children closer to the Bund even sooner than the Bundist literature and agitators would have. The first ones[13] were those same parents who wished to protect their children from danger.

[Page 1202]

The actions of the fathers had an opposite effect, which the fathers unfortunately did not understand.

The studying youth from the gymnasiums became involved with teaching the Yeshiva students to write and read Russian, and to do arithmetic. The workers also studied Yiddish. Enthusiastic students of Gemara and mussar [Jewish morality] took to worldly education with fervor, and drew closer to the political revolutionary parties in Kovno.

Like tens and hundreds of other youth from my area, I too was taken by the stream. The romanticism of an illegal organization was alluring. The clandestine meetings in the forests, the narrow “schodkes” in which the university students used to read their lectures, literally enchanted every boy and girl to the point of religious ecstasy. They turned aside from their fathers and mothers, left the Beis Midrashes, gave up the Gemaras and everything around it, and devoted themselves to the new movement.

I left Kovno in 1905, when I was 18 years old. At that time, Kovno had a distinguished record of Bundist activity. I left Kovno in order to avoid several years in Siberia or jail that would have been coming to me had I not run away. I do not know anything about the other political and Socialist parties that arose in Kovno during that epoch. I only know that a half century ago, every younger or older worker, and perhaps every member of the intelligentsia, stood under the influence of the Bund or some other Socialist party.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Lita (Lithuania)

Lita (Lithuania)

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 31 Dec 2010 by LA