|

|

|

[Page 45]

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

Jewish Amdur, the little town where I was born, was wiped out from the face of the earth by the hand of “Satan the destroyer” together with the thousands of towns and villages in the old home. Amdur was situated in the heart of the Grodno Gubernia, where Jewish families lived during hundreds of years and produced a great number of Rabbis, scholars, writers, poets and other well–known personalities. The little shtetl Amdur, which was no more than a small dot on the map of the Lithuanian Gubernias, was the whole world in the hearts of the local Jews.

Geographical Location of AmdurAs mentioned, Amdur was in the heart of the Grodno Gubernia, not far from the capital Grodno, or, as it was sometimes called by the Lithuanian Jews – Horodna. Since Grodno was an important town of Torah study and great rabbis, it was sometimes called by the Hebrew name Har Adonai.[1]

[Page 46]

In the neighborhood of Amdur, other towns – larger and smaller – were situated: Koznice, Adelsk (a very small shtetele!), Sokolka, Krynki, Swislocz – the Jews called it Shishlewitz – Berestovitz, Wolkovisk, Luna, Skidel, Wolp, Ros and others.

The writer of these lines is 55 years away from the era that he is trying to depict. During this time, Amdur passed through many hands. In 1895, when I left Amdur, it was under the rule of the Russian Czar. During WWI it was occupied by the Germans and later by the Bolsheviks, and after the peace–treaty was signed it was allotted to Poland. In the Second World War it passed again from country to country, and today – if it still exists – it is under Russian Soviet rule. It can be said that geographically and politically it is part of Russia.

Amdur, an Important Locality in the PastI do not possess documents or other writings concerning the importance of Amdur as a political, social and commercial center. Old Jewish men would tell me that in the past, when Grodno was under Polish rule (until 1772, when Poland was divided between Russia, Germany and Austria), Amdur was known also by the name “Little Danzig”…

[Page 47]

It was common knowledge that Amdur was once the capital of Poland, and the Sejm convened there in a historic session, at the time of the battle between Poland and Lithuania. This “Polish Rule” in Amdur lasted only one night; still it may be considered as a stroke of luck for a shtetl…

I would like to remark here that a copy of an Amdur Jewish Community register has been found in the library of the historian and philosopher Shimon Dubnov. The register contained episodes and events in the Jewish community until 1824. Unfortunately this copy – like so many Jewish valuable documents – was destroyed by the Nazi beasts.

The Number of the Amdur Jewish Population

Statistics, or keeping track of the number of Jews in the shtetlach was considered by the Jews unnecessary. According to the Talmud, it was forbidden to perform a census among Jews. So who would think of finding out how many Jews were living in Amdur at any time?… I don't know the number of Jews in town before WWII, but in my time the estimate was 200 Jewish families. If we consider 5 souls per family, we would have about one thousand Jews in Amdur by the end of the 19th century.

Amdur Streets

To speak about “streets” in Amdur would be an overstatement. There were three “main” streets: one was the Grodno Street, the other was the Volkowice Street and the third was the Krienky Street. All three were named after the three larger towns in the Grodno Gubernia. There was akso the Myestchanski Street, but we have given it a different name – we called it the Goyishe Gass[2] This street we shall describe separately, below.

The three main streets mentioned above were long, and the houses stood in a straight line, more or less. However, in the other streets the houses seemed as if someone has just scattered them here and there, without any plan. One of the neighborhoods in town was called “Mitzkrinak.” I cannot determine the origin of this name, but it was said that it came from the Polish “Njemetzki Rinak,” which meant “the German market” – the reason being the symmetrical shape of the houses and the fact that the place was always clean…

Almost all the houses were made of wood and most of them were covered with straw, a reason for the many fires in town. During the sixteen years that I lived in Amdur, I lived through many such fires, which have deeply influenced my childhood years. One of them, the most terrible of all, has left the population literally with only their shirts on their backs. The entire town went up in smoke.

[Page 49]

The fire started in 1882, when I was only four years old and I remember it as if it were happening today. In Amdur they even counted the years from that time on: this or that event was a number of years before the fire or a number of years after the fire… Amdur had its own unique calendar – the “fire–calendar.”

Before I left Russia to go to Argentina, they began building brick houses in Amdur. Henech Lichnyaver and Yankel Farfels built two large houses, and later the Great Synagogue [di groise shul] and the Beit Hamidrash [house of learning] were rebuilt, brick walls and a tin roof.

The Goyishe Gass

The street at the far end of the town was the Myestchanski Street. As fitting its nickname, all its residents were Christians, while most of the streets in the center of town were inhabited by Jews. These were two entirely separate worlds. True – we lived, traded and worked together, we were neighbors; but we were strangers to each other – Jews were strangers to Christians as were Christians to Jews. The Christian street ran as an extension of the Jewish street. Yet, as long as we, Jewish boys, would walk along the “Jewish area” all was good and well; but as soon as we

[Page 50]

“trespassed” into the Christian area, we felt right away that we were in galut[3] – not at home… A strange thing: in the entire town – actually in the entire town – where the Jews lived there was not one dog in sight; as soon as one crossed the border into the Christian area dogs ran around and barked – and what can be the feeling of young Jewish children among “goyish” dogs?…

It was typical, even among Jewish farmers, living in the villages, that very seldom a dog was seen around the house.

Well, well. Shem and Cham, Jacob and Esau, brothers of the same parents, and still so different.

|

|

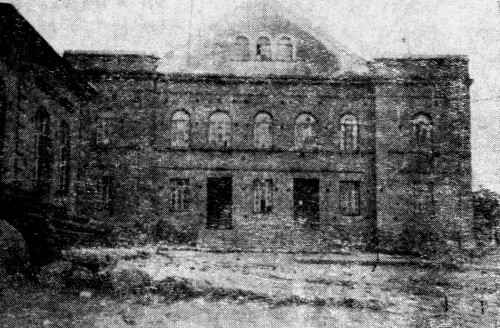

| The Amdur Synagogue and the Beit Hamidrash (on the left) |

[Page 51]

The Great Synagogue and the Batei Midrash

Amdur possessed a Great Synagogue [Groise Shul], three “Houses of Learning” [Batei Midrash] and a Hassidic synagogue.

After the great fire in 1882, the Great synagogue was rebuilt. In was now a very beautiful building, tall and spacious, constructed according to the architecture of religious buildings of that time. I remember that people would come from the neighborhood towns and villages to see and admire it. The Torah Ark and the platform where the Torah was read – gifts from two well-to-do Jews in town – were artistic masterpieces. The synagogue was the pride of the Amdur Jewish Community.

The great Bet Hamidrash could accommodate almost all Amdur Jews. Its artistic furniture was decorated with carvings of fruits and flowers. The initiator of this artistic work was a young man called “Itche the bachelor.” He was not married, obviously, and entirely devoted to religious art. This “artist” reminds me of another “artist” in town, also unmarried and with a nickname – “Shaul the spinster.” These two “artists” had to endure the mockery of the town people, who insisted on making a shiduch [match] between the “bachelor” and the “spinster”…

The other two Batei Midrash were named after the two rich Jews who donated money to build them: Sender's Bet Hamidrash and Bergman's Bet Hamidrash.

[Page 52]

In the old home, rich Jews were interested in having their name remembered, and for this purpose they gave money to build schools, Batei Midrash, synagogues, Talmud-Torahs, Yeshivas and other institutions. We had in Grodno, for example, the Soloveitchik Bet Midrash and the Bergman Talmud Torah, combined with the Yeshiva; in Vilna – Rav Meile's Kloiz and so in the other towns and shtetlach in the “old world.”

The Hassidic synagogue served as a center for the Hassidim in town, who belonged to various Rebbes. There were the Slonim Hassidim, the Stolin, the Kobrin, the Karlin, the Kock and the Nowyminsk Hassidim. Most of them were learned in the Torah; the Kocker Hassidim were real scholars: Efraim Abes and Leibe Chana-Etes in particular.

Since, however, in later years the difference between Hassidim and Mitnagdim diminished, some of the Hasidim prayed in the “regular” synagogues, so that not always a minyan could be assembled in the Hassidic synagogue, especially in the winter, when there was not enough wood to warm up the place. The story went, that in the place where the Hassidic synagogue stood, had once been the Hassidic Shtiebl of R'Chaim Chaika from Amdur, a good Hassidic Jew who conducted a Hassidic “Court.” Amdur was the greatest Hassidic center in Lithuania, at the time when the war between the two Jewish sects – Hassidim and Mitnagdim – was at its peak.

[Page 53]

In addition to the above-mentioned synagogues, there were many minyanim in our town, where Jews would assemble and pray betzibur [prayer quorum, lit. “with the public or community]. In the summer, we could hear through the open windows how Jews sang their Sabbath and Holiday prayers. I remember four minyanim: Motye the butcher's, Yankel-Moishe the tailor's, Leizer Shaul's and Yakov-Yosef's, both of them turners (lathe operators).

Translator's Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Indura, Belarus

Indura, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 5 Mar 2014 by MGH