|

|

|

[Page V] [Page 346]

With a sense of its sacred purpose, I have accepted the difficult and responsible task of perpetuating the memory of the Community of Busk which was destroyed. Facts were not in my hands as all traces were obliterated. There were no diaries, notes, documents or other reliable testimonies available, moreover, there was no possibility of access to Municipal documents or to search through the archives of the Courts or any other Government and Municipal archives in which documents referring to the Jewish population had been stored for hundreds of years.

I relied upon the inhabitants of the town residing in Israel who remembered and could relate events, who would assist in this worthy task. To my regret, only few encouraged me while carrying alone the burden of collecting the material, editing and producing the book.

After the event, it is difficult to explain and it is unbelievable how and with what I started to build up this project – brick-by brick.

Brother and sister, dear friend and honoured reader. My apologies for any omissions in the book. Many sources of information and writing were lost to me and also, I was limited in time as I am not on my own.

The chapters of folklore and habits are not the efforts of professional writers but are a collection of living memories from days gone by. For reasons already mentioned above, I have omitted certain factors, charitable institutions, orphanages, political parties, personalities, religious habits, etc. and for all these omissions and mistakes, I apologize. May I hope that in spite of

[Page VI] [Page 345]

all the defaults, the book will be a suitable memorial to the memory of the town and everyone will find therein some remembrance of something lost.

Accept the book in its present form for its good intentions, patient labour and the long and precious time spent on it.

I thank all those who aided me. Firstly, I thank Mr. Nahman Blumenthal who wrote the Historical chapters in Yiddish.

To Prof. Dov Sedan for his chapter: Busk and its surroundings. Thanks.

To the youthful friend of the Poet David Koenigsberg of Busk, the journalist Mendel Singer for his notes and assessment. Thanks.

The great writer Shai Agnon for his contribution, the third chapter: “a tale of a pot” from his book Hachnasat kala, the entire proceeds of which was given to the “wagon driver” (Ba'al Agala) a Jew from Busk: “Koh Lehai”.

To the poet Shimshon Meltzer for his writing in appreciation of his friend and the last Hebrew teacher in Busk, native of our town, and its poet Elazar Shmuel Berkun. Many thanks.

To my friends from New York – the brothers Asher and Israel Padwa. To Regina Kremnitz. To Shamai Zipper and to others who made possible the publication of the book. Many thanks.

Many thanks to all.

Abraham Shayari, Editor

Abraham Shayari

The town of Busk is situated in Eastern Galicia, 36km from the city of Lwow (Lemberg), and 36km from the town of Brody and about 30km from Zloczow, the birthplace of the poet Imber, the author of Hatikva. The railway station at Busk is in the village of Krasne, about 6km from Busk. It is a central depot from which the trains travel in every direction: to Lwow, Zloczow, Tarnopol, Brody and Rowne in Russia. To and from the station, passengers used to travel by horse-drawn carriages which were run by a few Jewish families in Busk.

The name “Busk” originates from the Ruthenia language meaning “stork” and thus its emblem was a stork. A statue of a stork made of steel was attached to the roof-top of a kiosk in the centre of town.

Busk is built on a hill and is surrounded by brooks and rivers. The largest river is the famous “Bug” which flows through the middle of the town. Her tributaries are the Peltew from the east and the Rokitna and Solotwina from the west. In spring, the snow melts and all the brooks and rivers overflow. At this time, the town looks like an island in the midst of a sea, a kind of miniature Venice. Slowly the floods recede leaving behind them pools of water and marshes in the vast meadowlands around the town, making the area into a natural nesting ground for the many storks that come.

There are six suburbs surrounding Busk. They are populated by Polish and Ruthenian peasants, artisans and other workers. A

[Page VIII] [Page 343]

few Jewish families lived in each suburb as well. The Jews worked in agriculture or had retail businesses (i.e. groceries, tobacco stores). They were grain and cattle traders too and even a few artisans. The suburbs were called: 1) Lipi-Boki. 2) Niemiecki-bok. 3) Dluga Strona. 4) Krotka Strona. 5) Wolany. 6) Podzamcze.

Busk was under the jurisdiction of two officials: the regional officer who's seat was in the neighbouring town of Kamionka Strumilowa, and the governor of the whole province “Wojewodztwo”, who's seat was in Tarnopol.

Busk is surrounded by rich and fertile farmlands and forests, enabling the peasants of the surrounding villages to farm, raise cattle and breed work and race-horses. The Jews of Busk traded with them in grain and cattle and made an honest livelihood.

Many of the surrounding farms were the property of the Polish Earl Kazimierz Badeni who was an Austrian patriot and a favourite of the royal family of Habsburg in Vienna. At one time, Badeni served as Prime Minister to H.M. Franz Joseph I from the house of Habsburg in Vienna. Earl Badeni often visited Busk and inquired into the lot of the local Jews. He knew many personally and spoke with them in Yiddish. Often, he exempted poor Jews from paying the town taxes. The only remnant left of Earl Badeni's family is a grandson, Kazimierz, who is Cardinal in the Taciturnos Monastery in the Polish holy city of Czestochowa. Busk is a very old town. As early as the 11th century, Polish earls and counts fought over its ownership, handing it over from one to another. From the beginning of the 19th century, Busk became the property of the Badeni family.

[Page IX] [Page 342]

There is no historical source regarding the presence of the first Jewish settlers in Busk except for an edict written in 1510 and issued by the Polish King Zigmunt, ordering Christians only as eligible for election to the Town Hall. This edict clearly shows that Jews were living in Busk at this time. Other legal documents involving Jews and written in the year 1500 note that there was a Jewish area in the town called Ghetto. Reliable sources show that there was a well-founded Jewish populate in Busk. Neither an organized or autonomous congregation, the Jews of Busk were affiliated to the large congregation in Lwow (Lemberg).

With increased political disturbances during the 17th century, (especially in Poland's eastern provinces) the position of the Jews of Busk turned for the worse and many were killed. There is proof that by the end of the 17th century, only 400 Jewish souls were alive. All were poverty stricken, toiling night and day for their mere existence.

Busk, a town of many streams and brooks, always served as a strategic point in war. The river Bug was considered a natural stumbling block in war and both attacker and defender desired to establish its frontline along the Bug.

The town was consequently laid to waste by both. Houses were burned down by Tatars, Turks, Swedes, Cossacks and Poles. Citizens were robbed and murdered. Naturally, the Jews suffered most of all.

Peace and stability returned to Busk in 1772 during Austria's occupation of Galicia. Economic conditions improved and a more liberal and tolerant attitude was accorded to the Jews. At the beginning of 1860, a big improvement in the plight of the Jews came about. Throughout Galicia, Jews were permitted to purchase rural lands, properties and farms. Most of the commerce and trade were conducted by Jews. They were allowed to organize their own communities which were comparatively free and autonomous. The

[Page X] [Page 341]

Jews of Busk recovered economically. They dealt in commerce, rented farms, bought lots in town and built houses.

At this time, Dr. Leo Sheps lived in Busk. Dr. Sheps was born in Busk and graduated from the medical faculty in Lwow. He practiced in Vienna and then returned to Busk to open a clinic. As well as being a doctor, he took part in public affairs and did a great deal in improving health conditions of the population.

His son, Morris Sheps was born in Busk in 1833 and attended high school and university in Lwow. In 1854, he began studying medicine in Vienna but later switched to journalism and became a very influential newspaper writer.

His articles in the “Neues Wiener Tagblatt” show how he fought for a liberal and democratic government. He also favoured an Austro-Franco alliance as against an alliance with Prussia. Many noted French writers and statesmen were friends of Morris Sheps. One of his closest friends was the famous statesman Georges Clemenceau, known as “The Tiger”. Clemenceau, a passionate defender of Dreyfus, was a senator and was elected twice as Premier of France. Once he journeyed to the Jewish cemetery in Busk with Morris Sheps. There, Sheps paid homage at his father's grave and showed Clemenceau his town of birth. Upon return, Clemenceau wrote an article about his visit to Busk. In this article he wrote: “In addition to storks, geese and ducks, Busk is populated by Orthodox Jews. These Jews are very poor. They have small stores or work as artisans or peddlers. They are clad in rags and live in such a state of poverty that they arouse a feeling of compassion for their pitiful state. It is difficult to say whether they are aware of their miserable conditions since they are always seen with a humble smile on their faces”.

Although Morris Sheps lived in an aristocratic society and became a noted writer, famous for his progressive ideas and statesmanship, never did he deny his Jewishness or feel shame for

[Page XI] [Page 340]

his birthplace. Up to the time of his death in 1902, Morris Sheps visited Busk often to honour his father's grave.

The name “Sheps” is probably derived from “Shabthai”. Some historical sources claim that the false messiah Shabthai Zvee had many followers in Busk. There is some reason to believe that the family of Sheps was for some time active in the Shabtai Zvee movement, therefore assuming the name “Shabthai”. Later, they returned to the Jewish community changing their name from Shabthai to Sheps.

At the beginning of the 20th century there was a great wave of immigration to the United States. Many Jewish artisans, small merchants and other unemployed left Busk as emigrants to America. Among them were Mr. Max Kremnitz and his wife Regina. Mrs. Kremnitz is an active charity worker and is now the President of the Busker Ladies Auxiliary in New York.

In August 1914, (the start of World War I), most of Busk's Jews fled in lieu of the Russian invasion. Some of these refugees reached Vienna while others settled in Bohemia, Munkacz in Hungary or other places far from the front line. The refugees quickly adapted themselves to their new environments. They found work, established businesses and most of them did not return to Busk.

At the end of World War I in 1918, the Austrian monarchy collapsed. Busk as well as the whole of Eastern Galicia became a battlefield between Ukraines, Bolsheviks and Poles until it finally became part of the Republic of Poland. All these battles reduced the Jewish population causing a new wave of emigration to America.

Among these emigrants were Mr. Simon Zipper and the Padwa brothers who are now outstanding members of the Busker Society in New York.

With the establishment of Polish rule in Busk in 1920, life slowly turned back to normal. Influenced by the national

[Page XII] [Page 339]

Renaissance movement of that era, Zionist clubs and Youth movements were organized and blossomed in Busk. With the help of the Busker Auxiliary's Relief Committee in Boston, Mass., a Mutual Assistance Association was founded which was headed by the late Dr. Kutin Shabthai. Through the initiative of Mrs. Rosa Kutin, a diligent and educated welfare worker and by the active support of Mr. Karavan and Mr. Kuhn of Boston, Mass., an orphanage was founded which could care for up to 40 homeless children, and a public kitchen, which provided food for the needy and the poor.

The Population of Busk under Polish Rule Year General Population Jewish Population Percentage of Jews 1921 6,148 1,533 24.9% 1931 7,010 2,600 22.8% Under German Occupation 1941 1,800 1942 2,000 1943 7,494 in Ghetto

Today, one Jew who fled Busk at the outbreak of World War I is living in the town. His name is Fridman and he is the uncle of our friend Dr. Benjamin Friedman of New York. But recent reports tell us that this last Jew has left too.

Education

Busk had two government-run (7 year) elementary schools for boys and girls but no high school. Wealthy sent their children to the neighbouring high schools in Kamionka – Strumilowa, Brody, Zlochow and Lwow. Those who could not afford the tuition studied at home as autodidacts. Many passed their final examinations successfully and went out into the world in search of a university that would accept them for the continuation of their studies. Busk had

[Page XIII] [Page 338]

No Yeshiva although any student wishing to continue his religious studies after 'Cheder' could learn in 'Clause'. There, the local rabbis helped them in the study of the Talmud and other Judaic books. There were quite a few outstanding scholars, well versed in Judaica as well as in general studies who learned as autodidacts or with private instruction.

The Jewish national renaissance movement was felt in Busk right from its beginning.

The pupils of the 'clause' as well as other students studied Hebrew. In 1908, an evening school for the teaching of Hebrew was established. The school's first teacher was Mr. Israel Baruch (Hahn) who is living now in Haifa, Israel. He has agreed to relate his impressions of the first Hebrew school in Busk as a contribution in memory of the town on one of the pages of this book.

Hebrew schools were founded in 1921 contributing to the spread of spoken Hebrew as a modern living language as well as to the understanding of the Bible. The study of Hebrew also produced many 'Chalutzim' (pioneers) for Eretz Israel. Many youths continued their studies of Hebrew in Teachers' Seminaries and Hebrew High Schools and other institutions for higher learning in Lwow.

The Jews of Busk took an active part in various Zionist activities. There were branches of all the Zionist Youth Movements: “Hashomer Hatzair”, “Gordonia”, “Achvah”, “Bethar”, etc., and groups from all the Zionist political parties: “General Zionist”, “Hitachdut”, “Revisionists”, “Poalei-Zion left” and “Yad Charutzim”. Busk even had a football team and a sport club called 'Bar Kochba'. Several 'chalutzim' from Busk joined the 3rd Aliya to Israel. Through the many hardships and difficulties of life in Israel at that time, there were many who stood firm and persevered. One of these Chalutzim is Meyer Dror (Shore), the founder of “Hashomer Hatzair” in Busk. Mr. Dror built his home in Kfar Yechezkiel and established a prosperous plant export business.

[Page XIV] [Page 337]

Busk was a very important link in the long chain of events in the history of the Diaspora of the Jews in Europe. The Jews here contributed proportionately to the national renaissance movement and the building of Eretz Israel. They fought in clandestine ranks of the Hagana and in the open war for the Independence of Israel.

All the Jews of Busk were killed, destroyed, exterminated in the cruellest ways by the Nazi murderers. They shared the tragic lot of all European Jewry.

We, the few who live in Israel under close cooperation with our dear friends, natives of Busk living in the United States, dedicate this book as an eternal monument in memory of all the innocent martyrs of the holy congregation of Busk.

Peace to their souls.

A.Shayari, Editor

Georges Clemenceau accompanied by his close friend Morris Sheps, a native of our town, visited at the end of the nineteenth century Busk. Upon his return to France he dedicated a whole chapter to Busk named “Busk” which was published first in a daily paper and later included in his very interesting book: “Au pied du Sinai”.

In 1922 this book was translated in English by A.V. Ende entitled: “At the foot of Sinai”.

I would like to make clear to the reader that Dr. A. Coralnik named the stories of Clemenceau's' book: Short Stories of Jewish Life.

Here is the chapter in full.

O. Clemenceau

A desolate village at the end of Galicia close to the Russian frontier, it is all built of wood and mud. In the leprous houses the plaster is crumbling, the woodwork shows cracks and fissures and attempts at repairs have been made with patches of leather, tin and filthy rags. On the corduroy road–bed of the marshy streets, long teams are painfully swaying to–and–from making the weary traveller bob up and down on his couch of straw. Ducks and geese are waddling about among the coming and going of big

[Page XVI] [Page 335]

muddy boots. Out of these boots rise the forms of emaciated Jews with glowing eyes under Talmudic locks; Ruthenians whose coarse hair mingles with the sheep wool of their garments. Mongols and Kalmucks, red, blond or black with powerful jaws, cheek bones abruptly protruding beyond the flat noses and little slanting eyes shining out of haggard faces. Slavs of diverse origins in long white coats, their star–like blue eyes beaming a false innocence. A camp that has migrated from Asia and has suddenly been arrested in the mud and to complete the vision, in the open plain, a village of tents around which are slumbering a black crowd of half–naked gypsies.

What is most striking in Busk, next to the ducks and the geese, is the Jews; unkempt, restless and gentle, carrying on all industries and all trades. The poverty of these people is extreme. One does not know whether they suffer from it or not as they pass along, sordid, lamentable and with a perpetual smile of obsequious envy. Perhaps they are not unhappy?

Their domain is the village square, a large parallelogram of greenish swamp lined with low huts that are filled with hideous din and bustle. All the length of the road, rose in the form of a sidewalk, on the trunks of trees or on boxes used as benches, they huddle frightfully ragged forms, motionless in oriental resignation. Sallow–skinned children with open mouths and big sheepish eyes, long wisps of hair fluttering about their cheeks, fraternize with the ducks on the dung heaps. Strange housekeepers, draped in nameless things, carry pails emitting unpleasant odours. Through the open doors of the wretched habitations, miserable pallets show their rotting straw amid all sorts of decaying refuse.

Here dwells a race, active, industrious, with long agile hands, reaching out for sustenance, a patient people capable of the most marvellous endurance as of incredible persistence of effort, contented with little, ambitious of everything, humble, timid, implacable,

[Page XVII] [Page 334]

charged with four thousand years of will power. The Pole governs Austria it is said. The Jew, being a universal negotiator, holds in his hand the Pole, whether peasant or magnate.

“When I want to buy or sell anything” said the Baron of Busk, “whatever it may be, I call a Jew. His relations with all the markets of the country, his understanding of business, his interest in keeping me as a customer, are to me an assurance that I am going to be served promptly and well. There is no large landholder in Galicia who, for business of any kind, is not forced to address himself to the children of Israel”.

The man who spoke thus owns sixty thousand hectares. His estate is a manor. The greater part is forest, of course. The hour of the revolution which will cut up into parcels these vast Galician domains has not yet struck. I doubt whether anybody thinks of it. The Galician, whether Slav or Jew, is accustomed to his poverty. The agricultural industries bring the proprietor but little profit and assure the worker only a rather precarious existence, but each seems content with his lot. There is fatalism in the blood of Asia.

The very plain castle with large servant quarters is surrounded by a beautiful park through which flows a river. Strange contrast of aristocratic lawns with a sprinkling of horticultural artifices and the savagery which begins on the other side of the wall.

I was advised to visit the Ruthenian church. Irreverently we push open the gate of a wild garden and meet a tall, old man, in black garb and a straw hat of vast proportions, absorbed in smoking his long pipe. It is the curate. As he bows in welcome, he displays his handsome, smooth and firmly modelled cranium, a profile of aquiline distinction softened by a pair of eyes as blue as a baby's.

A certain vessel hanging on a pole near the door receives the friendly pipe and the good smoker, without smoking, accompanies us across a field with here–and–there a few centenarian trees, in

[Page XVIII] [Page 333]

The generous shadow of which nestles the modest church, its' skeleton of laths covered with unpainted tiles. Beside the sacred temps is a barn–like structure with gables and a heavy wooden belfry with absolutely bare sides. The interior of the church is luxuriously ornamented with barbaric images of which the excellent old gentleman seems quite proud. He shows us his gold embroidered vestments, a handsome chasuble with flower design of the last century and he makes us notice that it is of French material. Some court gown of a friend of Louis XV, perhaps, which after strange vicissitudes, is in this quiet place, piously expiating the sins of departed flesh.

While the priest naively makes us admire a little chapel crudely carved in wood with a simple knife, the work of his hands on long winter evenings, a dozen peasants, men and women have entered and eagerly share the feast spread before our eyes. As we pass the altar we find, on the floor, a little wooden box which these people have placed here. His last art object duly exhibited, the saintly man politely salutes and without transition, slipping on a black soutane, intonates pious chants which the chorus of peasants, candles in their hands, duly repeat.

We are expected at the Jewish cemetery. We accompany one of our friends who, after a brilliant career in the Viennese press, has come on a pilgrimage to the grave of his father, a physician of Busk who had spent his life in nursing, succouring and tenderly caring for the pour of all races and creeds. As a Jew, he had helped all the unfortunates of his race who suffering had gripped his heart by so many bonds of common history. As a man, he served humanity unselfishly, as one may well believe for, judging from the Busk of today, the Busk of fifty years ago can hardly have assured a fortune to the healer of countless ills that Providence sent to the poor. The old wooden house which had been his home and now resplendent in a coat of fresh white paint, was point out

[Page XIX] [Page 332]

to us. After fifty years of faithful labour and service, he had simply and without any pomp, left it for his resting place in the graveyard.

At the gate some ragamuffins were watching for us and joined us without a word. I had once visited the ancient Jewish cemetery in Prague which all guides recommend to the tourist. It is like an avalanche of old gravestones that had been tumultuously tossed about by the hurricane of age. Elder bushes, a century old and never trimmed by a human hand cover the stones with their dark foliage. It is difficult to find one's way through this thicket. Fragments of inscriptions are still discernible, clasped hands too and symbolic birds and heaps of little stones deposited by pious visitors in homage of the departed. It is an ancient custom of the desert where the traveller devoutly adds his pebble to those heaped on the mounds.

I found no trace of this custom in Busk but the hands were there and the birds too, still enlivening the tombstones with their primitive images. The Jewish cemetery of Busk is a virgin forest, an impenetrable jungle of trees, brambles and weeds growing in untrampled freedom. Old trunks are moulding at our feet, heavy branches beaten down by age or storms burden with their long agony, the young shoots that sprout between them in the will to live. There is no path or anything resembling one. White birch stems crowd close together as in battle array, interlacing twigs, spines bristling in defence, arrest the explorer.

The miserable troop that had followed us in silence got ahead of us at the first step and, passing between the trunks, holding apart the branches, slipping like adders into the densest thicket, guided us to the grave which wed sought. Humble creatures they were with long bony faces, their beards, coats and boots shining with the same sticky ochre–like dirt. But there was an incredible intensity of life in their vivid black eyes, well protruding from their sockets and glowing with fire. We followed them through the underbrush, accompanied by the

[Page XX] [Page 332]

noise of broken branches, lashed by rebounding twigs, stumbling perhaps over moss–grown stones buried in a mess of dead wood. A sumptuous living frame for this picture of death they were and they suggested a sensation more powerful and more beautiful than our pretentious cities of the dead, full of grimacing figures and disgraced by mendacious epitaphs.

At last we reached a group of four stones which our guides had already stripped of their covering of vines and brambles. Their fingers scratched the lichens to lay bare the writing which the stone would jealously keep secret. Then all the hands pointed to a stone leaning over as in a faint: “There it is”.

And suddenly all these haggard faces, even when they smiled, contracted as with suffering, were ennobled by the solemn gravity of the most sublime sentiment known on earth. The eyes were fixed in contemplation of the mysteries of the world; thoughts that commanded respect rose from under the fur of worn–out bonnets, greasy little caps. Each of these beggars was at this moment a pontiff. One of them, sacristan or rabbi I know not which, with authoritative voice and in well–scanned lines pronounced words that ravished, transporting with ecstasy all who heard them.

“Here we are before your grave, friend. We bring to you your son who had not appeared before you since the day when he marked with this stone the place of your great rest. Life had taken him into the world where your long–continued efforts for his good through your continuing to live in him, assured the success of your progeny. Ever present among your kin you thus carry on your work on this earth. That is why your son comes to pay grateful homage to you. In times gone by, before life, you were united in eternity. His birth separated him from you, gave him a life of his own. And now, in thought, he comes to reunite with you and to revive you in himself even as you did”.

The invocation, of which only this brief passage was translated

[Page XXI] [Page 330]

for me, seemed to me of superior beauty. I wish I could literally quote the naïve address to the neighbouring dead that followed, asking them to entertain friendly relations with him whom we had come to honour and expressing the hope that they too would thus be visited by their kin!

With difficulty, we groped our way back through the thicket and found ourselves before a type of a barn where, on the solid earthen floor, were huddled in a circle women, children and old men, the poorest of the poor in the village. It is customary to give them alms and my friend passed before them and dropped money into their outstretched hands; There then appeared a board with bowls decked with inscriptions that claimed the generosity of the visitor for various institutions. I saw bills dropping into the bows one after another; not one of those charities was forgotten.

As soon as we came out, a mob of paupers presented themselves, pressing forward at the news that a son of Israel who had gone forth from Busk had returned with unheard–of treasures which his hands was dropping into every yearning pocket. It was a veritable race as to who would get closest to him. The twelve tribes were there seeking the occasion to ameliorate their condition.

“I knew you when you were a little tot” said an old man. “I am a relative of –“; “I am a friend of so–and–so whom your father cured”, they eagerly proclaimed.

Thus the beneficence creates a claim against the benefited or his descendants for the benefactor and those that follow him. One of the speakers had lost his calf, the other his horse. All had been victims of some accidents. Never in so short a space of time was heard such an accumulation of catastrophes.

Implored, caressed, dragged forth, deafened by a hundred stories, our friend followed by those poor whining wretches was

[Page XXII] [Page 329]

forced, in order to reach his hospitable lodgings, to pass through a crowd of persistent claimants that barred his passage. By the use of our shoulders and our elbows, we succeeded in breaking away from them. But, at the gate of the castle, another formidable attack awaited us. The whole synagogue was there with the great rabbi in the lead, a marvellous Moses of Michael Angelo whose head, crowned with a high fur bonnet, lost itself in a torrential beard in which the waves of silver alternated with those of ebony. A long discussion took place for the house of God was still unfinished and if the visitor would but move his magic want of gold, it would be built and all of Busk would rejoice. I must admit that our friend did not strike me as a very fervent devotee at the altar of Jehovah. Nevertheless, it would have surprised me if childhood memories and the natural feeling of solidarity with a great tragic race had not made him add his stone towards the erection of the edifice where his forbears had worshipped.

The gate was finally locked. While the chattering crowd retired, disappointed that the galleons vanished as dream–like as they had appeared, we gradually regained our composure. The neighbouring gypsy camp was tempting me and I suggested a visit before our departure. I had retained the vision of a little gypsy of perhaps ten years who, that very morning, had for a copper coin frantically followed our car across the holes in the road while at each of her leaps, like that of a rag doll, the smiling head of a bronze marmot bobbed up, madly tinkling its bells on the shoulders of the swift runner. A gate at the park permitted us to get out into the plain, unnoticed by the eyes of restive Israel, and soon we were in the midst of the tents that were planted at the border of the forest.

Compared with the Jews we had just met, these people live in happy serenity. Pariahs, the degraded refuse of the castes of India; they carry in the folds of their cloaks what was left of them from their native land. Towards the horizon which ever recedes, they are

[Page XXIII] [Page 328]

going all the time, marching towards the unknown, disdainful of the present sojourn and ever hopeful of a better one. Serious and without restless agitation, without the rudeness of conquering races, they take across the planet their tranquil contentment with everything. What is to them the possession of some earth? Where chance guides them, they plant their long poles, attach the canvas and their palace is ready. Their little horses feed on the grass while the gypsy, resplendent in copper buttons, goes from farm–to–farm in the quest of worn out pots and kettles that need the restoring hand of the itinerate tinker.

Earth offers plenty for the children and the troop, enriched by beggary and occasional depredations, appears to enjoy the solid comfort of nomads living on next to nothing. The depth of their eyes, diamond black, their placid features, their solemn gestures, reflect the fatalist soul of the orient. Little boys of ten to twelve, stark naked, voluptuously recline like young wild animals, only their head of heavy coarse hair now and then bobbing up from the couch of green. Women likewise crouching on the grass, look at us with supreme indifference. Their shining tresses end in chaplets of silver coins, evoking a vision of brilliantly decorated idols.

Under a big tent there is a gravely reclining and handsome black divinity, radiant with silver coins. Her couch is a rug of violet colouring forming a frame of sumptuous brightness. Blue spirals are rising from her pipe and seem to fascinate her like a dream. At her feet is a little girl of about six who lights one of her mother's pipes on the hearth fire and seems to derive in finite joy from it. It is a certain view of life which makes the oriental, with all its inwardness; adapt his customs to life under the misty skies of the occident.

The orient has also given us the Slav peasant, fashioned by the despotism of Asia who doubles up at our sight and without even knowing us, in passing, kisses our hands.

From the orient too, come these restless Jews whose

[Page XXIV] [Page 327]

contemplative faculty is so serious disturbed by militant contact with occidental society. Of a philosophy less disinterested than the Aryan, a stranger who as harmless wanderer carries with him the implacable malediction of his brothers, the Jew, however accursed, has attempted to conquer the hostility of the world into which dispersion by conquest has thrown him. Scorned, hated, persecuted for having imposed upon us gods of his blood, he has wanted to redeem himself and to perfect himself by overcoming untoward circumstances. For this task, nothing was spared; no suffering, no torture counted, no vengeance was scorned. There is no more astonishing history in the world.

And because it now happens that these people have resisted menaces, stakes and forced conversions because with all their vices and their virtues they have entered the social organization of our own vices and virtues, because they have drawn from their stock of good and evil a power of action at least equal to our particular power of good and evil combined for the conquest of wealth, because they have possessed themselves of our weapons and have learned to turn them against us, I hear that their systematic extermination is desired. Thus, one can revive the hatreds of those defeated in the contest for domination, one can resuscitate plans of persecution which are but an admission of defeat; but how can one found upon all this something that will last?

The enormous power of Israel in contemporary Christendom cannot be denied. All things remaining as they are, the activity of this enduring race, this marvellous producer of energy can, in my opinion, only increase. For Aryan idealism, I would not consider this a misfortune. Besides, each people have good and bad characteristics and all supremacy of race seems to me to contradict the deepest interests of our manifold humanity. But, when the faculties of a race have so miraculously adapted themselves to the social order of the present, as different from the past as it is certain to be from that

[Page XXV] [Page 326]

of the future, what can one say unless the race and the economic order in changing give us other results. The Jews will not be destroyed. The sultan himself, with hundreds of thousands of Armenians massacred, will at the end be conquered by Armenia. Israel, having gone forth alive from the middle Ages, cannot be suppressed.

Instead of condemning a race whose lucky or unlucky faculties have made it a factor in present society, instead of crying cowardly that it must be annihilated to give us room to live – why do we not try, simply and more justly, to frame a more equitable, a more disinterested social code, in which the power of selfish appropriation – be it Jewish or Christian – is rendered less harmful and its tyranny less crushing for the great mass of humanity. Then the Judaism of Judaea, if its cleverness made it sovereign of a society of barbarous egotism travestied by the false gold of charity and the no less triumphant Judaism of Christianity whom fate has permitted to have its chance, will no longer know the evil temptations of today and will be contented within the limits of an individualistic development compatible with a superior notion of social justice. Without violence, without massacres and persecutions, Semitism remaining what it is now as it is typified in many children of Ham and Japheth, could no longer present the danger which it is said to be today.

Fools are those who believe in founding liberty upon the growth of tyranny! Less license to selfishness, more room for pity. Clear the roads that lead towards justice; bar the avenues through which unhindered triumphant oppression is entering. How short–sighted it is to dream of a change of oppressors! To kill the oppressor is but to replace one by another. What is needed is to attack him in his possibilities of action. Thus, the wretched Christians of Paris or the wretched Jews of Busk will be efficiently assisted in their personal efforts against the heavy yoke with which they are burdened by their big brothers of all races to whom the law, at present, is contented to say: “Crush, dominate, abuse!” and who to crush, dominate

[Page XXVI] [Page 325]

and abuse. What the Christians, who are after all still masters of the world, need above anything else, is to better their own ways then they will not need to fear the Jews who may be reaching out for the crown of opulence which has ever been coveted by men of all ages and of all countries.

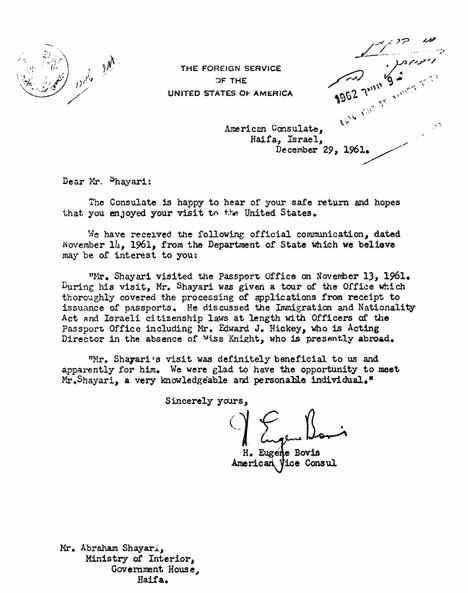

As you remember, in autumn 1961, I visited the United States. The rich country of unlimited opportunities and possibilities. The land in the Western Hemisphere where, during the last two hundred years, millions of people have found shelter; people who were homeless, stateless, unemployed, undernourished, people of all levels, different religions, various nations from all parts of the world, whose existence was insecure. They were without fixed occupations unable to activate their hidden initiative, became productive workers, and rooted in their new state like “trees in streams of water”. In their new country these people were converted into productive elements and were rehabilitated into normal human beings, became self–reliant and have developed this generous land which rests on progressive foundations, on freedom in thought, in deed, in creation, enjoying, through their efforts, all the country has to offer. This and more. They have not forgotten their past. They have devoted themselves to the ideal of mutual aid and have taken upon themselves the noble purpose of working in the spirit of “let they brethren live among you”, to give a helping hand to the needy and to near and far.

I was very happy to meet you and to watch your activities in the factory, in the workshop, in business, in public work, in social activities and even on how you spend your energies as a result of your efforts. You are linked up with all good deeds connected with you directly or indirectly. I have seen you carrying out your heavy

[Page XXVIII] [Page 323]

responsibilities in your wonderful work for Israel especially and for your brethren from Busk in Israel in particular. May your strength increase!

In the pages of the Busker book, I have permitted myself to thank you for all your kindness, for the fine welcome which was given to me and my wife and for the hospitality and kindness shown to us during our stay with you in New York.

When I was touring Washington, D.C. I made many friends not only among our own people and everyone showed me courtesy for which my sincerest thanks.

I was received warmly everywhere, at private parties, by the public and by the administrative officers of various Government departments. I am still full with impressions which will remain with me for a very long time and I can truly say – forever.

My visit to the Head Office in the capital where the Statutes are prepared for American citizenship, made it possible for me to exchange opinions and views with prominent personalities of the Law and thus received a clear explanation of certain paragraphs of the law regarding the position of an American who migrates to Israel and acquires Israeli citizenship automatically; what the law is, what is permitted and what is not permitted for a citizen holding dual citizenship.

With your kind permission, I have allotted to my credit a positive page as compensation for the valuable “load” of information which I brought with me upon my return from my visit to the United States of America.

Yours, Abraham Shayari.

|

[Page XXX] [Page 321]

|

|

| Mr. Shayari honouring the tomb of the unknown soldier at Arlington National Cemetery in Washington D.C. |

|

|

| On the way to the White House |

[Page XXXI] [Page 320]

Haifa, 22nd January, 1962.

Mrs. Knight, Citizenship & Passport Dept., State Dept. Washington D.C.Through Mr. E. Bovis, the American Consul, Haifa.

Dear Mrs. Knight.

Permit me to apologize for the long delay in thanking your trusted assistants and particularly Mr. Hickey for having guided me and given me such full and comprehensive explanations when I visited the offices of your Division on 13th November, 1961. The reason for the delay was that I only returned to Israel in mid–December and to my office desk at the end of that month. Naturally, on my return, I found many outstanding matters, both private and in the office which, of course, I was anxious to begin disposing of.

I was very sorry that I was destined to visit your division at a time when you were absent from Washington and I therefore did not have the opportunity and the honour to meet you personally, although, judging from the well organized and efficient cooperation there and the high intellectual standard of your chief assistant, I recognized you as a person of great knowledge and an exceptional personality.

I was very much impressed by the working of your Naturalization & Passport Division, of which you are Head, and I am full of wonder at the new office techniques displayed there.

I have learned much and my visit to your Division has been very useful to me, for which I thank you and your staff and of course the American Consul in Haifa, Mr. Bovis, who initiated and made possible my visit to the States and who granted me without any doubt or hesitation the necessary visa for the visit.

I am now interesting myself in American Citizenship Law and all the material which I have received from Mr. Hickey. I hope to return one day in order to learn more and there is much to learn from you. As is written in the Bible: “From all my teachers I have become wiser”.

I am taking the opportunity to convey, through Mrs. Knight, my warmest greetings to all the employees of the Division and many, many thanks to all those with whom I came in contact.

Yours sincerely,

A. Shayari

|

|

| Dr. Benjamin Fridman |

Benjamin Fridman

M.D., 98 Norman Avenue,

Brooklyn 22, N.Y.January 24th, 1964.

My dear Avram,

You are asking me to give you a biography of me. It seems to me that in this memoir, the topic should remain the Heroic Jewish Community that died in the terror of the industriously murderous Germans, that we should accentuate and project to the future generations the true picture of our wonderful ancestors to whom we pay a fitting tribute and although this is a backward glance. Another echo of the sigh, we will underscore our determination that this cataclysm should never be allowed to repeat itself. Rarely a day passes without thinking about my family whom I am never to see again; my dear parents, brother and almost my entire family whose premature loss I deeply grieve.

I do wish to thank the entire staff of workers for helping to preserve the memory of our home and town in their coverage of the frightening events surrounding its death.

If, however, you need to know something about me: I studied in the gymnasium on the Zygmuntowska and from there went to

[Page XXXIV] [Page 318]

Engineering for one year and then switched to medicine. Prague became a terrible place to study and I had an argument with my chemistry Professor and decided then to go to Italy – Bologna and Padova. Here I finally graduated and then left for the United States. The life here in the early thirties was very hard, depression and no jobs available for medical students, natives as well as foreigners. But, somehow, through the generosity of some people, I was placed in a fine hospital where I spent almost two years and then ventured into private practice. So as you see, nothing spectacular or dramatic happened to me that didn't happen to thousands of others in my days.Regards from my family.

Fondly yours,

Benjamin

by Jacob Goldberg, New York

New York, April 23rd, 1959

The end of 1943 was lucky for me. I had managed to escape from a camp, to find my wife and my sister and her son who were hiding in the woods and, immediately afterwards, to acquire a more permanent “place of residence”. This was in the village of Angelowka near Brody in Poland on the premises of Mr & Mrs Kubalski who, risking their lives, gave us permission to live in their barn, or rather, in a small shelter attached to the barn which we built ourselves. The living area was small – six feet by four feet. There were eight of us there: Mrs. Sztombrember with her two sons; my sister with her son; my brother; my wife and myself. We received our food through

[Page XXXV] [Page 316]

a hole we had cut in the shelter's wall. It was a well camouflaged opening. For greater safety, Mr. Kubalski covered it with a hay–cutter. The shelter itself which was erected impromptu from old planks was covered on all sides with hay and straw so that it resembled a haystack. Although the walls and roof were put together loosely, we felt the shortage of fresh air. Now and then, when circumstances allowed, my brother and I would leave our “house” at night to get some air and stretch our legs. We could do this because Mr. Kubalski's barn was on the edge of the village and close to the forest. It was unlikely that we would meet anyone in that area, especially after dark.

Today, it is difficult to imagine how we could have lived under such conditions for any length of time; lacking air and water for washing and knowing constant hunger. All these “inconveniences” were nothing, however when compared with our perpetual fear of being detected. Any small thing – a loud word – a nervous movement of the hand, even a stifled cry – was enough to betray us. Shut away in the shelter, we never knew what was happening outside. There was no way of knowing from which side or at what moment danger, which equalled death, would come. Furthermore, we were weighed down by the fearful conviction that one day we would have to leave the shelter, inferior but nevertheless safe, for the woods where death lurked behind every tree and bush.

Slowly, spring came. The snow melted and the meadows began to bloom. A new season was in sight. One day at the beginning of March, 1944, Mr. Kubalski came, gasping with the news: the Germans were taking over the barn. Soon they would bring over the horses and install a field kitchen in the barnyard. “They have already arrived in the village. It is too late to run away. This is the end!” A few minutes later we heard the voices of soldiers leading horses. We saw nothing and could depend only on our ears. What eventually happened we learnt from Mr. Kubalski.

The Germans brought about thirty horses. There was not enough

[Page XXXVI] [Page 315]

room and the soldiers decided to remove the hay–cutter. Mr. Kubalski did not wait. Convinced that we would be discovered at any moment, he and his family left the house.

We heard several soldiers shouting and swearing, climb on our shelter, probably to rest. Re–arranging the straw, they found hay hidden underneath. This produced jokes about how stupid the farmer was to try to hide hay from them while, little–by–little, they fed it to their horses. Soon the hay was almost gone and so was our hope. We sat rigid – the slightest movement would have been enough to give us away. Every second seemed an eternity. We could not speak of course but I was sure that each of us had the same thought: Alright, let them come, let whatever must happen, happen; anything will be better than this. Our 'roof' began to disappear. I do not know whether my imagination tricked me or whether I really saw a soldier's hand reach for the hay right above our heads.

We were saved by the signal for lunch. The soldiers left the barn. We took advantage of the free time to repair our 'ceiling' by grabbing hay stuck in the walls and stuffing it in the roof. In the meantime, probably encouraged by the fact that we had not yet been detected, Mr. Kubalski returned. Passing near our shelter, he whispered as though speaking to his wife: “we can no longer be of help to you. Try to run away tonight. Some of you may be saved….” He then walked up to the officer in charge and asked him to forbid his soldiers to use the hay, complaining that it was all he had, that he needed it for his cow and horse and that he had small children who had to have milk, etc., etc. The officer began shouting – in typical Nazi fashion – that the blood which was being shed daily by the soldiers of Germany could not compare with the farmer's stupid hay, but faced with Mr. Kubalski's stubborn plea; he finally gave in and promised that no more hay would be used.

After dinner the soldiers began to lie down on top of our shelter. The officer's promise didn't seem to amount to much because soon

[Page XXXVII] [Page 314]

the supply of hay above our heads began to melt. However, by then we had begun to accept our predicament and somehow had gained hope; ignoring the fact that single movement could betray us, we put our sixteen hands to work removing hay from the walls and stuffing it in the ceiling.

I still do not know whom we ought to thank for our good luck – Providence or the stupidity of the soldiers, because, for an hour at least, we placed the hay right in their hands. Not one of them thought of reaching down as far as the planks. Had this happened we surely would have been detected.

Night came. Fortunately, the soldiers did not sleep in the barn. We were left alone. Knowing that we could not last through another day, we decided to dig a tunnel under the foundation of the barn, which fortunately was shallow, and escape! At 2a.m. with spoons and knives as tools, we were ready. I looked out – escape was impossible! Next to the wall was a huge pile of wood barring our way. Any attempt to move it would wake the soldiers up.

There was no other choice: we had to sneak through the barn and the yard where the Germans slept. To stay was impossible – our supply of hay was just about exhausted. By running away openly at least some of us might be saved. We said a brief prayer and prepared to go: my brother first then the women and children. I was to be the last.

The barn door had a primitive lock which could be opened either from outside or inside. My brother tried the door – no good. Through the hole in the wall he noticed a padlock. In despair, forgetting all caution, he cried: “No good – the Germans have fastened it!” His voice must have frightened the horse nearest the door for at that very moment, the horse reared and hit the door with tremendous force. It flew open before us. Immediately, as if under orders, we plunged forward. The woods were close by and by the time the soldiers knew what had happened, we were safe. From

[Page XXXVII] [Page 313]

afar, we heard their cries and shouts but by then we were protected by the great and dark dignity of the forest. Nothing would hurt us until dawn, at least.

Of the eight inhabitants of the shelter at Angelowka, six are today in the United States, one is in Israel and one is no longer among us. Our friends and hosts, the Kubalskis live in Poland.

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Busk, Ukraine

Busk, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 30 Sep 2015 by JH