|

|

|

[Pages 144-146]

Translated by Renee Miller

Edited by Fay Bussgang There once was a town of Jewish tailors – Brzezin. From early dawn until late at night one could hear the music of the Singer sewing machines. It was the music of hard work, of intense anxiety, of a hard life, but also of noisy youth, semi-intellectuals, observant Jews, Hasidim who lived and had aspirations in the small Jewish town Brzezin.

The Nazi savages extinguished this life forever, transformed it into ashes. Only a few Jews from the tailoring town Brzezin, by some miracle, remain, scattered over the entire world, individuals who were witnesses to the German cannibalism.

May these words, frail in print, but inscribed not with ink but with blood, be a modest contribution to the matseve [gravestone] for my native town, Brzezin.

Brzezin was one of the oldest and most popular Jewish communities in Poland. When this community was established, it carried the name Krakowek [Little Krakow]. At that time, the community extended from the Strykower highway to beyond the Jewish besoylem [cemetery] to the surrounding hills. The Polish noblewoman, Anna Lasocka, had brought the first weavers from afar into this community. Then the community developed even further and began to broaden its borders. At that time, the town already carried the name Brzezin.

Jewish tailors came to Brzezin from many places, and after several generations, the town developed its own type of tailoring industry, by which it was known all over the world. A cottage industry was the main occupation here. As early as 1772, Brzezin was famous for its mass production in tailoring. Until 1914 the great Czarist Russia was flooded with the inexpensive products of Brzeziner tailors. In the years between the two world wars, the export of Brzezin industry was spread over many lands in Europe and into other parts of the world. In this, the great Jewish magaziners [owners of clothing enterprises] – exporters such as Frankensztejn, Tuszynski, Sulkowicz, and others played a great role.

The Jews in Brzezin did not only work, they also participated actively in the socio-political and cultural life of the town, had their representatives on the town council – in town hall, and had their religious and secular educational, cultural, and social organizations. Materially, it was a life of Jewish poverty, but spiritually, socially, and culturally, it was rich.

September 1939

The Germans are on the move. Mobilization and turmoil. From western Poland, thousands of Jews are fleeing in panic. Masses pass through Brzezin heading toward Warsaw. Brzeziner Jews leave their sewing machines and go out into the streets in order to give assistance to the transient Jews passing through. They share food, give medical help, and provide beds for those who are delayed for a day or two in town.

Wednesday, the sixth day of the war. Brzezin gets bombed. Fire and smoke cover the town. The streets – Saint Ann Street, a part of Pilsudski Street, and Rogowski Street – disappear in smoke. At that time, many inhabitants and refugees from Lodz, Kalisz, and other communities are killed.

Several days later, the Germans enter our town, and a series of persecutions begin – house searches and looting, round-ups for work, insults, humiliation, beatings, and torture. A large number of Jewish intellectuals, various leaders, are arrested and deported. They never came back, and since then nobody knows what became of them.

Yom Kippur, after the Germans had set fire to the synagogue, they led old Rabbi Borenstajn into the street and set fire to his beard. Goaded, beaten, exhausted, and ridiculed, they dragged him away to the train and shipped him off to Krakow. Broken and sick, he came back to Brzezin several days later, only to be deported later to the gas chamber with all the elderly.

Round-ups for work take place daily. A portion of those seized are sent away outside of town, on the way to Galkowek, where people are tortured and then buried alive. Spread out along the roads that go from Brzezin to Galkowek, Witkowice, and Koluszki and also into the surrounding forests, are mass graves of Brzeziner Jews, who were buried alive.

In the second half of the month of December, 1939, the SS-man Kaufman arrived, and several days later, the first curses began. From an entire group of streets, Jews were rounded up in order to be deported. After great effort on the part of the Jews Zagon and Klajnbaum – who made it clear that these Jews, tailors by trade, could be used to work for the army – and, most importantly, with the help of a gigantic sum of ransom money in cash and in gold, the abuse was stopped. Workshops to serve the military were created in Brzezin.

In the first months of 1940, a ghetto was established in Brzezin. The Judenrat (Jewish Council) was formed with Fiszke Ikka at the head and Perlmuter, known by the name “Shmayde Fiak” (complete drunkard), as the Police Commander. As if there were not enough Germans, we also had to put up with bitter torment even from Jewish “leaders.”

|

|

In the ghetto, despite hunger, cold and repression, the work went on in the tailoring workshops. They made clothing for the Germans. From time to time German “visitors” used to come to Brzezin. Especially known were the names of the Gestapo men – Fuchs, Richter, and Swinto. Those names evoked terror and horror among the Jewish population in the Brzezin ghetto. Using various methods and means, they took from the Jewish population the last remnants of their possessions – gold, jewelry, and furs. They used to get drunk, and the Judenrat would have to supply alcohol – wine, liquor, and cognac. They wanted women, and the Judenrat had to provide women. “Chairman” Fiszke docilely obeyed, carrying out all that was demanded of him.

Nevertheless, life in the ghetto during the year 1940 passed, one could say, “normally;” we somehow survived. Later, the situation worsened beyond comparison. Already in the first days of January 1941, a command suddenly came to furnish ten Jews who must be publicly hung. On the site of the burned down synagogue, a gallows was erected. The Judenrat had, according to the command, to furnish ten Jews – and the Judenrat carried out the command.

The entire Jewish population of the ghetto was brought to the execution and had to view this event. At twelve noon, with hands bound behind their backs, the ten Jews were led to the gallows. Among the victims was a mentally ill Jewish woman, Mundzia; there was another woman among them, Fajga the water carrier. The rest were men; among them were Judel the water carrier, Urbach, Hauzer, and others. Hauzer went to the gallows with the outcry, “We go to a martyr's death; take revenge!” Judel the water carrier called out, “Until now I was a simple water carrier: tomorrow I will be among the holy martyrs!”

After that it was quiet for several weeks, and then it began again.

A command was issued that all the elderly and sick must be brought in to be “branded.” All the elderly and sick were collected in Badower's building – men and women. All had to undress completely naked. First the SS men arranged entertainment. The naked men and women had to dance and demonstrate various things that are simply impossible to describe. They forced the Jews to perform various distinct scenes, beat them on their naked flesh, and kicked them. After that, when the SS men had finally had enough of this “exhibition,” they began to stamp all those that were there. They put the stamps on their sexual organs. The healthy ones returned home, those that got branded with the letter “B.” The rest were sent away to die.

On the fourteenth and fifteenth of May 1942, a gang of SS men came into the Brzeziner ghetto with the chief, [Hans] Biebow. Biebow's name already had a reputation at that time. That name of his aroused horrible fear in everyone. Biebow issued a command that mothers had to bring their children to him, up to the age of ten. It rained on that day in Brzezin; it rained torrentially, and through the streets of the ghetto came neatly dressed Jewish children with their hair freshly washed and combed, led by their mothers. The mothers were crying, and the children calming them, trying to quiet them, “Mama, don't cry. Why are you crying?”

The children were all assembled around the town square near the town hall; they remained there the entire day with their mothers. Night fell, the tired children fell asleep on the ground near their mothers. Some children cried, begging, “Mama, let's go home. Why don't we go home? Why is it so dark? Why don't we turn on some lights?”

Suddenly at three o'clock in the morning, there was a great commotion. A drunken clamor awoke the children. A command was heard – turn over all the children – and right after that, they began to tear the children away from their mothers. A lament from the mothers and children, a cry, an entreaty, and the SS men tear the children away from their mothers' clenched hands. Children scream and cry, “Mama, I want to go with you, Mamusia [Mommy]!” The mothers fall at the feet of the SS men in entreaty, kissing their filthy boots. The SS men kick them with their boots, strike heads, prod them, and a contemptuous laughter echoes through the hall, mixed with the sound of pointed tips of rods on the flesh of the crying mothers. The mothers plead, “Take us along also; we want to go together with our children.” It does not help.

|

|

They take the children away, and in the hall remain the battered, aching, and sobbing mothers. One of the Gestapo, Zeifert, shouts out, “The mothers must so perish,” and goes out. A reverberation of child-like screaming and crying is heard from outside. After several minutes, it becomes entirely still. At daybreak the SS men come in to the mothers and with shouts and beatings, chase them outside into the street.

The next morning, the Brzeziner ghetto was empty of children. No longer were there children in the ghetto. Only one mother remained in the ghetto with a child; this was Mira Rozen. The Judenrat took a chance for her, and the Germans were so magnanimous that, for the time being, they pardoned the life of a Jewish child.

When the mothers turned to the chairman of the Judenrat with the question “What happened to our children? Where did they take our children?” the chairman answered, ”The children are in Lodz, with Rumkowski [head of Judenrat in Lodz ghetto] in Marisin; they are there in a children's home. You will see them soon.”

Several days later, they did the same thing to the grown-ups that they did to the children. The liquidation of the Brzezin ghetto had begun. People were rounded up from their homes and shops and carried away to their deaths.

Within a short time later, the Brzezin ghetto was liquidated – Brzezin was cleansed of Jews.

In the month of July 1942, the Jews of Brzezin began to be brought into the Lodz ghetto. Those who came told of terrible things, the way the liquidation had taken place in Brzezin. Through special gangs, we called them “Rol-komandes,” who were called into the town, the Jews were driven together into one place, shot, murdered, robbed, and a selection carried out. The healthy ones were packed 100–150 people at a time into one train wagon. Many women with children and sick people were taken away to Chelmno [death camp].

A Jew from Brzezin brought a postcard from the Grabow rov [town rabbi], in which he reported that he had spoken to three Jews who had fled Chelmno and told him what was happening there.

The card was brought to a meeting of the ghetto committee in Lodz.

What we lived through then is hard to communicate. By then we knew everything. It was decided to inform all parties about it, as well as Rumkowski, the alteste [elder] of the Judenrat in Lodz, so that Rumkowski would no longer be able to say that he did not know what was happening to people. We told him that he should no longer be an accomplice of the Germans and that he should no longer attempt to buy off the evil decree – a tactic that Rumkoski categorically rejected.

Comrade Abraham Apowski, former member of the town council in Brzezin, was brought in as a member of the Lodz group (of the “Bund”) to direct the self-help activities in the ghetto. The Bundist party group from Brzezin amounted to fifteen men.

[Pages 147-148]

|

Translated by Renee Miller

Edited by Fay Bussgang I will never forget the dark Shabes [Sabbath] day, a week after the outbreak of the war, when the Nazis marched into Brzezin and the destruction of our hometown began.

Very early on Shabes the Germans took Brzezin. We Jewish citizens waited in our homes, terrified because of the forthcoming events. Night came, a death-like stillness spread over the town. Suddenly, a flame lit up the heavens, caused by the burning down of our beautiful synagogue.[1]

The German murderers brought to the site of the fire our Rabbi Borensztajn, an elderly man upon whom we all looked as the spiritual father of our kehile [Jewish community]. He was forced to sign a document that he himself had set fire to the synagogue. Hitler's fire setters thought this would wash away the sin that they had committed against the Jewish population of Brzezin.

Then began the terrible persecutions inflicted upon us by German soldiers, together with the Brzeziner Volksdeutsche [Brzeziners of German origin].

The first victims were the wealthy families. Killings and robbings, as well as beatings with murderous blows without any reason, were daily occurrences. The “hero” of the first barbarous action was a local German, a former friend of ours by the name of Bach, a member of the sports club “B.K.S.,” the bramkarz (goalkeeper) of the local football [soccer] team.

Brzezin, the regional capital, became the focal point for the assembling of regular German army battalions. A regiment of the German Wehrmacht [regular army] was stationed in Brzezin. The local police were quartered in Korolenki's building on Sienkiewicza Street. The Gestapo [Secret Police] and the SS [Special Police] occupied Dr. Warhaft's private home.

Day and night without end the Stormtroopers would rampage through the streets of our town. The Obersturmführer [head of Stormtroopers], Manen Kaufman, a terrible sadist, would invade Jewish homes and issue orders for men, regardless of age, to gather in the courtyard in rows of five. Then he would begin to torment them with military drills. “Get down! Get up!” And during this orgy he would beat the poor wretches with revolvers and kick them in the head with his boots. At the end he used to pick out several elderly men and cold-bloodedly beat them with blackjacks.

The SS men set up a real butcher shop in their quarters. They summoned rich Jewish citizens, beat them, and forced them to give away all they possessed. Afterward, they sent the unfortunate Jews home, half bloodied and battered.

The systematic campaign to rob Jews lasted until the month of May. The murderous work was carried out with German “precision.”

In addition to the evil decrees, they humiliated us morally at every step. Often a German sadist would stop a Jew and cut off his beard, while a group of onlookers would stand around and amuse themselves by laughing and applauding the merriment. We Jews had no right to walk on the sidewalks – only among the pigs and on lanes in the middle of the street. This would be the filthiest part and the most dangerous. We wore yellow patches on our chests and backs. Under penalty of death we were not allowed to appear on the streets after four o'clock in the afternoon.

Later, we found out that the Nazis had decided to liquidate us, drive us out of town and drag us away to the crematoria. With great self-sacrifice, Jasza Zagon, together with Dr. Warhaft, carried out a plan to help during this terrible time. They persuaded a German officer who had shown mercy for Jews to travel with them to Lodz to the Handelskammer [Chamber of Commerce] to present a plan to the Germans and convince them that the Jewish tailors from Brzezin could be of use to the German Reich. This helped a bit, and they put us to work.

On the fifteenth of May 1940, they stuffed us like animals into the ghetto, fenced in with barbed wire. We worked twelve hours a day for the firm Günther and Schwartz. The living conditions were horrible. Two families occupied one small room, without any facilities. Hunger, deprivation, and cold reigned in the ghetto. Several diseases spread rapidly.

In the ghetto and at work, the Nazi sadists tortured us terribly. They were “artists” in discovering all sorts of methods to shorten our lives. Depressed and hungry, we surrendered. But they did not break our spirit. In every tortured Jew a spark of hope lived that the horrible hellish suffering would end and the moment of revenge would come.

In March 1942, posters appeared on the walls of the ghetto that the execution of ten so-called “criminals” would take place on Purim. They would be hung, and the entire population of the ghetto must witness the execution.

On the designated day, the gallows were raised not far from the Mrozica River (that the Jews called the rzeka [river, in Polish]), amid the remains of the half-burned outside walls of our beautiful synagogue.

Militiamen, specially recruited for the purpose, forcibly dragged out every Jew who refused to be a witness. It was thus that all the Jews of the ghetto were assembled at the site of the gallows. Many of us were torn apart; the nerves couldn't stand it. Indescribable screaming and crying were heard from the crowd. The desperate cries were borne up to the heavens.

|

|

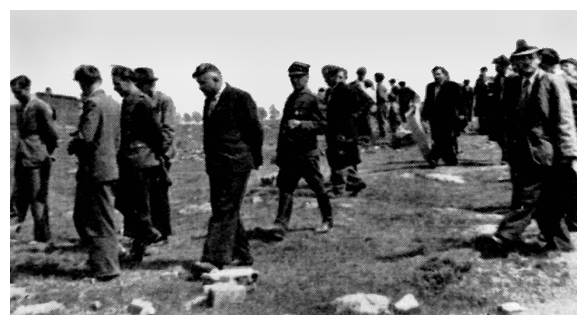

Jewish population onto the streets to be present at the “hanging spectacle” of ten Brzeziner Jews |

But then an SS man suddenly appeared and with his high, strong voice gave the order, “Be silent! If not, everyone here will be shot!” In an instant there was a deathlike stillness.

Those condemned to be hung were brought out. Upright, with heads held high, they approached the gallows without displaying the slightest fear of death. One, a homeless beggar, Judel Sochaczewski, who in his entire sad life never hurt a fly, cried out several times as he was climbing the steps to the gallows, “I go to a martyr's death for the whole town!”

|

|

Jozef Bialik Jobrusz the waggoner's grandchild |

After the execution, all the Jews had to march past the gallows with their faces toward those who'd been hanged.

In the month of May, another dreadful piece of news swept through the ghetto – the announcement of the liquidation of the ghetto and the deportation of all Jews from the town.

One day, Jewish mothers with children up to ten years of age had to gather in the marketplace. The unfortunate mothers experienced a short-lived happiness. They thought, in their naiveté, that they were being taken to a rest home with their frail children. How terrible was their disappointment!

The marketplace was immediately surrounded by SS men. Large trucks came to the square where the mothers and their children were gathered. The “action” [deportation] had begun.

In a bestial manner, the SS men tore the tiny children from their mothers' arms. Heartrending scenes were played out there; the shrieking and screaming reached the heavens. The mothers fought for their children like lionesses, but they had to surrender.

That is how they loaded thousands of children onto trucks and carried them away to the crematoria.

On the fifteenth of May, the Nazis drove the entire Jewish population of the ghetto out onto the streets.

On the nineteenth of May, six thousand Jewish souls were deported from Brzezin. Of these, only a small group remain alive.

That is how our Jewish town was destroyed.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Brzeziny, Poland

Brzeziny, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 20 Jun 2008 by LA