|

|

one in Hebrew and one in Yiddish

by Moshe Shuster

Translated from the Yiddish by Fruma Mohrer

Opening paragraph translated by David Goldman

| Allan Ira Bass dedicates this article to his mother, Ann Bass, née Hana Roitman, who told him, “We all came from the same small town, that is why we are so close to one another.” His mother loved her family dearly. And to all my Roitman (also Rothman, Rotman) relatives, past, present, and future, spread out throughout the United States, Europe, South America, and Israel - May you flourish while remembering those who came before you. |

The years go by, the youth is gone. Time turns the hair gray and puts wrinkles on your face. However, the tense, heart-stopping events we lived through and the youthful romantic feelings flash from time to time, just as if they had occurred yesterday.

I can still see the streets and small lanes of our hometown in Yedinitz.

Here is the small marketplace, the 'torhovitse' as we used to call it, where the peasants' fair, with peasants coming from the surrounding region used to take place. In the center was the church, whose church bells whenever they rang would strike a feeling of fear in me.

A few streets further away was the 'Patchova', a street where one simply took walks, where you could have a conversation with one of your own close friends, or where one discussed and argued with those of opposing views, and where the meetings of young couples in love took place.

Here one could forget the impoverished homes, that there was not enough food to satisfy one's hunger, and where one dreamed about a great brighter world.

This main street, the Patchova, was more than a kilometer in length, had everything in it, with activities going on in all fields. Here could be found both small and large grain merchants. Here were displayed the workshops of blacksmiths, barrel makers, carpenters, furriers, and other workers. Here one could find little stalls and all kinds of stores and little shops.

The real walk would start out from Chaim Weinshenker's home, whose daughters Lisa and Etel [the latter lives in Paris today] had a deep empathy for those who had the capacity to sacrifice themselves for the ideals of justice and progress. Their home, which was always crowded with youth, especially as Yente Shternberg was among them, became an 'open house' for us, in which we used to spend every evening together with Itsik Ackerman, Pinye the chauffeur, and many other guests.

[Page 140]

Right next to the Niemeshinitzer's apothecary and the bank where Guta Shpilberg worked (one of us, a very fine, intelligent woman] was located the hair salon of the pleasant and agreeable couple Mendele and Ruchele Reicher [the sister of Motye Reicher], where one used to step in for a chat as if one were with one's own intimate friends.

After the apothecary and the Premislav's oil factory, was located the Revkalevski's little shop of sweet ice cream and seltzer water, with boiled syrup, whose colors sparkled and tempted you to taste them. In this little shop, we spent our last penny every evening.

The dentist named Gukowski, and his family were warm and hospitable to guests. The children, Yasha and Revetcka, were very close and dear friends.

The Patchova Street was dominated by a relatively monumental building – the notoriously famous seminary. This great building with its gardens [today it is a public school], though it was supposed to be in theory a place to ordain priests for all of Romania – did in fact provided the greatest percentage of fascists, gangsters, and Jew-haters.

Many times, these seminarians, most of them sons of the nobility, beat up the solitary Jewish strollers who had come from the narrow tailors' street to take a little breath of fresh air in the 'romantic areas' under the willow trees, in the forest behind the seminary and near the stench ridden lake.

This actually happened to the writer of these very lines, who, together with a group of friends had the temerity one evening to sing a Jewish song, and moreover, a revolutionary tune. This was a good opportunity for the seminarians to befall us and attack and beat us 'to a pulp'.

Besides this, the Patchova Street was enveloped in greenery. It was the main center for the local aristocracy, the intelligentsia, and just respectable Jews who owned nice homes here and had gardens that led all the way down to the stream.

Here too was located Shmuel Drutzer's home and the small synagogue, and later a hospital. A little higher up closer to the road was the town hall and naturally the Police headquarters.

[Page 141]

Just across stood the private gymnasium, where for the most part Jewish youth studied, most of them sons and daughters of the wealthy or middle class from among whom were later recruited a large number of progressive activists and sympathizers. Every one of them deserves fuller attention to be paid to them.

On the same street, a little further down, practically adjacent to the poor neighborhood, was the 'Tarbut School'- a kind of 'people's school' where children were already studying various vocations – myself among them.

In general, the city itself, besides the Dubrow School, Kutcher's School, and the Tarbut Library, had many Zionist reading circles and organizations. Later, the Yiddish Progressive Culture Club and the Reading Room became an important center for the city's youth as long as it could remain legally in existence, given that this was a country where police terror reigned and where repression was a daily occurrence.

To this can be added the only cinema hall, the Garfinkel's, where older films were screened and where Yiddish theater troupes starred, among them the Vilna Troupe, which would come on tour to perform from time to time. Here lectures were organized such as the evening with Yoel Mastboim. The master wordsmith Hersh Grosbard performed here, as did the actress Chayele Grober and other Yiddish stars of the stage.

[Page 142]

As I close my eyes, images, and shapes of the past appear in my mind. The images follow quickly, one after the other. Here is my street, the street of the church, that stretches all the way down until the so-called neighborhood of the Moldavians.

I see before me my father, Meir Chaim, on his death bed and who came back from as far as Argentina. He left for the war of 1914-1918. He was imprisoned in Vienna and came back in 1921, only to die at a young age of typhoid.

Before my eyes appear my good-natured grandfather as well, Mates Schneider, with his white beard and the pure pious soul of a 'man of the people'. Together with them, I see before me my family and the neighbors --- all good, precious Jews, hard-working, harried, and tired out from searching for ways to make a living for their large families.

The large Jewish community of Yedinitz, as in almost all Jewish settlements in Bessarabia and other East European areas, was constituted of various types of people. Wealthy, propertied, middle class, merchants, tradesmen, 'beis-medresh' or synagogue Jews, storekeepers, butchers, tailors, shoemakers, smiths, bakers, wagon drivers, and just simple Jewish men and women, most of them very poor, whose poverty was plainly evident and visible. All of them lived with great hopes for a better future. These hopes ended for the great majority in the destruction of the Holocaust.

May these few words, which come from the depths of my heart, serve as a Memorial for a life cut off, a time which shall never arise again, and as a malediction upon the Nazi murderers and their partners.

Paris.

by Sender Harari-Hochberg

Translated from Yiddish by Asher Szmulewicz

I knew no other town, only you Yedinitz. Everything that can make a man happy, I found in you, Yedinitz.

There, I had a home with parents, brothers and sisters. I started to attend Cheder. I loved your narrow streets: I strolled “under the willows”, in the orchards and gardens, along your “streams”. I loved the fair, the crowd of gentiles with their horses, cows and sheep. Only the marching pigs in the streets disturbed my spirit. The evenings were beautiful, when the herd was coming back from pasture.

On Friday afternoons and festival eves the gentiles used to leave the shtetl. It was time to enjoy the smell of the fresh challahs, the pot roasts and the gefilte fish...

Then we would go to the bath house, in order to prepare ourselves for shabbat. Shabbat and the festivals were relaxing and calm.

I remember the selichos nights, the voice of the sexton waking people up to come to the service of the Lord, the sound of the shofar in the dawn of the month of Elul when all the creatures prepared themselves for the Day of Atonement.

On the night of Kol Nidrei, a forest of memorial candles was lit. Everybody was shivering as the cantor was uttering his prayer: “I am poor of good deeds”. Gentiles also used to bring memorial candles on Kol Nidrei night to the “Jewish school”. The whole shtetl was holy. Jews used to go back and forth from home to the synagogue with their yarmulkes, slippers, and white linen robes. During Succoth they used to go on the streets, with their etrog and lulav, on Hoshana Raba they used to go with the osier branches, on Simcha Torah with the Torah scroll. Also on Hanukkah, Purim, Pesach, Shavuot and, not to differentiate, Tisha B’Av. Each festival with its own traditions, food and instructive lessons.

[Page 144]

I loved to listen to the melody of the midnight prayers, prayers, the selichos, the elegies and the festival liturgical hymn. There was a longing for the past splendor of Judaism, for the Kohanim, the Levites from the Temple in Jerusalem, for the judges, the prophets and the kings. Who could equal our rich spirituality? Pork eaters or the thickheaded gentiles? They used to dare to curse the Jews and to promise that a day of revenge on us will come…

We started dreaming of rebuilding our own land, our Eretz Israel, with judges, heroes, peasants and wise men. We only needed to want it. “If you will” …

In 1931 when I was 20 years old, I left you, my shtetl Yedinitz, in order to become a pioneer, a kibbutz member in Eretz Israel. I did not have a room for myself to live in… Malaria, dysentery, furuncles were our lot. We worked hard but, in the evenings, we sang, we danced, we were happy… We saw the building of our land, how the dream became true.

And about you, my shtetl, we received terrible news. You were transformed into a cemetery for your Jews. In your streets and homes, our parents, brothers and sisters, infants and the elderly, were murdered. Your sidewalks and house walls became red from the splashed blood of babies… The rain could not wash it up. You became a death camp for the Jews living in the area. Your rivers were full of Jewish blood.

Who could imagine such a thing?

Who will have the criminals pay for their crimes?

I feel mercy for you, my shtetl Yedinitz…

And we swear: “This will never happen again”.

Masada Collective village (Jordan Valley)

by Yosef Magen-Shitz

Translated from the Yiddish by Asher Szmulewicz

| Yedinitz was, for us at least, a Bessarabian village without a past and a name. It was not mentioned either in any historical documents. It did not produce any celebrity, Jewish or not. Nobody stood out and it did not produce any major innovators in any fields of the human activities.

However, the village was famous for its long straight, sometimes crisscrossed wide streets, with the shape of a chessboard square which was called quarteralen (block). These blocks were a measure of distance. “Walk two or three blocks” people used to say, when asking where such and such person lives. The crossroads were called koltz, a Wallachian word, whose meaning is extremity or corner. Each block had four koltzen. Because of the straight streets people used to say that Yedinitz was built according to the Odessa plan. |

Secondly, Yedinitz was famous for its mud. Although all the other Bessarabian towns, shtetls, and villages had mud (even a city, the second biggest one in the region whose name means mud: Beltz), the Yedinitz mud was well known throughout Bessarabia.

Yedinitz was situated on the slope of a hill. When it rained, the water flowed down from north to south, carrying mud everywhere. Mud used to lie down in autumn after the rain. In winter, the mud froze. The snow covered the mud. When the snow melted then the real mud started. In the month of Adar (March), the spring sun started to shine, and the mud started to dry on the side roads. At first, it became hard and when walking on it, it was like walking on a rubber cushion. Later it transformed into lumps and in the summer months, it was scrubbed into a thin powder dust (porech).

Often, the mud was composed of a thin layer, and often, the depth of the mud was about a meter, especially at the koltzen. In the fair days, when peasants and horses squeezed the mud and it sunk well, we used to hear shouting and voices: carriages and horses got stuck in the mud and Goyim used to gather to help to free the horses and the carriages.

[Page 146]

First, the stuck-in-the-mud horse listened to the shouting via, heide, hop, hop, hop, but then the horse got stuck deeper and deeper, it became tired, and in the end, sprawled indifferently in the mud. Then the road was blocked by the horse, and this became a hazard to the gathering crowd. People brought poles to lift the horse. The animal was dragged by his feet and by his tail. This was called the Kode. Often after such a dragging, the horse was alone and the Kode was alone. There were so many horses that drowned in the mud.

The pavement and the little bridge

There was a stone pavement in Yedinitz in the Patshtave Street (Post Office Street) at the beginning, only below the bridge on the road to Dondoshen. The paving of the road started during World War I, and if my memory does not betray me, Turkish war captives paved the road. The pavement was soon destroyed. Anyway, it was the only paved section in the middle of Patshtave Street. On both sides of the pavement, the mud was still piled up.

Non-Jewish coachmen and Jewish cart owners did not like the pavement and preferred to go around it. It was softer, less shaky, and safer for the cart and the horse.

[Page 147]

Later, during the Romanian era, the municipality fixed the pavement. The budget was agreed upon, but most of the money went into the pockets of the municipality employees and the pavement remained broken and full of holes.

In the early 1930s, bridges were built on a few crossroads (koltzen). There were built from timbers. It was not designed by engineers. They were built by Katzap carpenters, plotnikes. Poles were stuck in the ground, and on top of them, were fastened large wood beams that constituted the bridge. More money went into the pockets of the businessmen than into the bridge-building. The bridges were meant to ease the traffic but going above the mud became a hurdle. Around the bridges gathered a pond of water and a heap of mud. Going through the bridge with a horse and a cart was like crossing the Red Sea. Most of the time people went around the bridge. It was easier to go through the thick ditch than going through the bridge.

|

|

|||

one in Hebrew and one in Yiddish |

||||

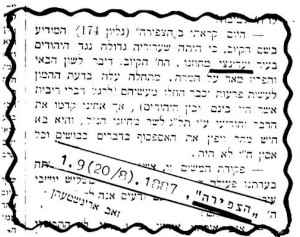

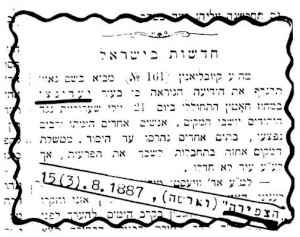

The press from these years, Jewish and non-Jewish related the riots against Jews in Yedinitz during the eighties (1880-1889). The Jews remembered that local Katzapes (the old Russians, “old roots,” an orthodox sect) made or tried to make a pogrom, we found two mentions of these unrests in the newspaper Hatsfira from the year 1887. In the newspaper edition of August 15, 1887, the Hatsefira article copied from the Russian newspaper Kievlianik, stated that in Yedinitz a bloody pogrom occurred on July 21, 1887: a lot of Jews were killed and injured, and a lot of apartments were ransacked. Two weeks later, the newspaper Hatsefira reported that a correspondent from Hotin (signed Zeev Arinshtehen) claimed that the first news reports were exaggerated. His version was: between Jews and non-Jews there was a hassle because of interest rates. The non-Jews started to do things. The Jews sent a telegram to the regional governor. He came to Yedinitz and stopped the mob.

[Page 148]

Story from once upon a time

We, all the people busy with the book, like the majority of our readers, were born around 1910. During World War I, and at the time of the change of governments, we were all children. The generation who remembers about the years 1880, 1890, and the beginning of the twentieth century, who remembers about the Russian-Japanese War in 1905 and about the October Revolution and World War I, is almost gone. Only their stories are left. Some of these stories were lost; the Jews used to live far away from the common news. A characteristic joke was told about a Jewess who shrieked about the Russian-Japanese War: Gentleman fights with the Russian and we came to help.”

Also, we were told about the pogrom of the Katzapes against the Jews around 1880, just after the common pogrom wave in the southern part of Russia which was then called in the literature: “Storms in the Negev.” After the pogrom, the Jews gathered and decided to boycott the Katzapes and not purchased from them anymore.

[Page 149]

The Katzapes were producers of eggs, chickens, potatoes, all kinds of greens, also melons, and watermelons. The Jews did not employ them and did not lend to them or sell them liquor but boycotted them. We were told that the Katzapes came to the Jews weeping and lamenting to stop the boycott. They promised they will not take part in any future pogroms against Jews.

An interesting story from a completely different person was told to me by Yankel the activist in the mid-1920s, when he was the director of the high school, and I was a high school student. He was an activist of the freedom movement Slobode from 1917 and always was a bit of a Bolshevik. I remember his explanations about what the Zionists were up to:

“The rich men are all the same. If they cannot suck anymore the marrow of the workers, then they sent them to Palestine, to exploit them better over there.”

Besides preaching anti-Zionism, Yankel the activist (later he was called storog) gave us, the boys around 12-13 years old, all high school students, lessons and about “he and she and the seven things,” in short, what is called today sex education.

Besides that, he knew a lot of stories from once upon a time. It is understandable that from these stories' point of view, all the young people nowadays are nothing and lazy. The “once upon a time guys” when Yankel was a youngster, were friends and heroes.

Once, for instance, Yankel and five other guys spent a day of a fair in the widow's tavern (I forgot the name) and drank a pot of wine. Youngsters from that time knew what a good wine means. Back then, a fair was not like today's fair: trading area, the horse-trading area, the upper one and the lower one, was full of Goyim.

One of the guys said:

“You know what? Are you ready to beat the whole fair full of Goyim and disperse them?”

Everybody agreed. The six Jewish guys, each of them, were such a fearful one. The heart was reinforced by the good glass of wine. The wine then was not diluted like today. They stood up and went out of the tavern.

Each of them took a stick and went to the lower trading area besides the church. Four guys positioned themselves at the crossroad from where people were coming in and out of the trading area, and two guys went inside between the Goyim. These two guys started to twirl their sticks and drag the Goyim toward the fair exit. There was a panic.

[Page 150]

The Goyim took what they could and ran away. Nobody knew what happened. People trampled one on the other and ran toward the exit to save themselves. But there stood the other four guys with their sticks. People who got through, got a knock in the head, on the shoulders, or wherever the stick knocked.

The fair was dispersed. That is how six Jewish youngsters knocked down a whole fair with thousands of Goyim. Several people from the shtetl testified that this event really happened.

There were no stories about good Jews, scholars, rabbis from the shtetl. People spoke about the large epidemic that cut off hundreds of lives and particularly the large cholera epidemic from the previous century. There were no stories about local revolutionaries, no stories about educated people or Chasidim or mitnagdim (Orthodox Jews against the Chasidic movement)

There were a lot of Chasidic trends: The names of the synagogues can testify: the Sadigerer house of study, the Hosiatiner, the Rashkever, etc. But people used to go to the Shtepaneshter rabbi even when Shtepanetsh was in Moldova (Romania) and Yedinitz was in Russia.

The pioneer of the modern education in the shtetl was Yehuda Shteinberg, the prolific writer and teacher. A lot of his first and famous writings were written in Yedinitz. Educated young people used to come to his apartment, although I was told by Reb Avraham Rosenberg, a Yedinitz native, and a Paris citizen since 1909 coming from the Hersh Ksils family (have lived in Israel for several years), Yehuda Shteinberg's wife was a frivolous person, should my writing not be harsh to her, and this issue was felt strongly in her home.

Synagogues and religious schools

Of course, there were in Yedinitz religious schools, with rabbis and assistant teachers. The most important task of the assistant teacher was to bring the children to school by carrying them above the mud. They oversaw cleaning a pupil if he soiled his pants.

Some modern teachers combined old methods from cheder with modern studies, and they even accepted girls. They learned grammar, but the tanach was translated word by word in Yiddish.

[Page 151]

They learned about modern Hebrew writers, some Russian, and calculus.

I learned from such a teacher for a while. In his school, one of the teachers was my relative, but I don't remember his name.

I remember an interesting event where the rabbi handled a difficult pedagogic issue, related to sex, in a school mixed with girls and boys using today's more modern methods.

We learned in the Shmuel I book about the relations between King Shaul and subsequent King David. We came to the verse that narrated that King Shaul promised his daughter Michal to whoever could bring him as a present of hundred Philistine foreskins.

The rabbi looked around and saw a girl named Ite among his pupils. He could not translate such a dirty word in front of her. So, he said to her: “Ite, Ite, go outside and ask what time it is.” Ite went out and the rabbi rapidly translated the verse: “So you should say: a present, the king does not need a dowry of a hundred non-circumcised stalks from the Philistines.” The slang explanation of the translation of foreskin in Yiddish came as a pedagogic reason.

That is the way to speak to boys. There were among the boys, it is understandable, someone who gave the girl the rabbi's translation, and especially the actual translation of foreskin.

The first teacher who conducted the method Hebrew by Hebrew was the teacher Hillel Dubrow z”l from Lithuania, who was brought in by the parents after he taught for a while in Odessa. Hillel Dubrow's first wife Tzipora z”l was from Yedinitz and also a teacher. She used to sing to us during the first days of school: “On the window, on the window stood a beautiful bird” with a Lithuanian-Ashkenazic accent.

We learned chumash not from a chumash book but from a book published in Odessa written by Bialik and Rabinski: Stories from the scriptures, where all the erotic stories were absent like Loth and his daughters, Yehuda, and Tamar, etc. But we discovered the forbidden chapters in our father's chumash. We relished it in the underground.

[Page 152]

We quickly learned Hebrew from our teacher Dubrow, whom we called Hamoreh,[1] and he did not teach us only Hebrew but also brought and gave us Jewish and Zionist spirit. He educated a lot of youngsters. Thanks to him the Yedinitz youngsters knew Hebrew better than all the other shtetls. Hillel Dubrow left Yedinitz and later came back to a teaching position until his aliyah in 1936.

I am not ashamed to say that when I came across him in Tel Aviv, I was full of embarrassment and respect as when I was his student. When he saw me, he called me Yossele, as he used to when I was a boy.

After Dubrow left, we learned from the poet A. L. Yagolnitzer, then we went to high school, which was established by a Christian called Wilenski as a Hebrew high school. Dubrow also was there as a Hebrew teacher. The high school was very quickly Romanianized, and Hebrew was made an optional subject.

The Romanization of the high school is a subject in itself. It upset everybody. Suddenly in the shtetl everywhere there were small placards in Romanian and Hebrew: “Jews we are, Hebrew we learn.”

Just at that time, a delegation of the United Jewish Appeal arrived at the shtetl: Yaacov Wasserman, Moshe Rebelski, and others. A meeting was scheduled in the synagogue against the Romanianizing of the high school. After fiery speeches, Wasserman asked: “Who is against Romanianizing?” Everybody raised their hand. This, of course, did not help because the parents wanted, in fact, the Romanianization of the high school.

In the shtetl, there were complaints that the above-mentioned small placards were linked to the United Jewish Appeal. Now, how can I say, we can disclose that the placards were made by the children using rubber typographic stamps. The writer of these lines was Israel Kolker (who lives today in Lviv) and Shalom Serebrenik (now called Caspi and lives in Herzliya) and other pupils.

Every teacher at that time previously sinned with his pen[2]. I want to remember other teachers who were also authors: Gandelman who emigrated to America, Greenspan who came from Israel, he was from the second aliyah and passed away in Yedinitz. Yashtshikman, Toporowski who made aliyah and became famous with his philological research.

[Page 153]

All of them have passed away. The last teacher in high school was a former high school student, Zalman Zisselman (in the meantime he finished his pharmacist studies) and I believe he now lives in Beltz, Bessarabia. In the last years before the war, when Zionism was passionate, the quality of the Hebrew teachers declined in Yedinitz.

Translator's footnotes:

Translated from Yiddish by Asher Szmulewicz

| I almost don't remember about the Russian government on the eve of the war. I remember only, and this is blurred, about a dressed-up Sergeant (Uriadnik) and a few guards (strazhnikes). The forthcoming war, in its first years, stays in my mind along with the epidemic, disinfection, and through the hozlech.[1] |

There was a typhus epidemic and separately, a strain typhus epidemic caused by lice. We placed a small bucket of carbol liquid, karbolke zhidkost, into a sprayer made from two small wheels. Then we blew this solution on those who were infected. This was our preventive disinfection method. In addition, the sanitation committee went from home to home t to look for creeping insects inside clothes, inside the shirts, in the men's winter pants, in the women's bras, especially when their husbands were not at home. The sanitation committee members were impudent, and the women members were corpulent.

The deserters and the desertion

All the time men were called for military conscription. The Jews never wanted to serve in the army, especially during wartime. People tried to get out of it by “pretending.” Men who pretended were called “pending.” The conscription commission gave all kinds of colored tickets. Somebody with a red ticket had to serve, a yellow ticket meant a postponement of conscription, and a white ticket was an exemption ticket from military service. It was the ideal ticket.

The conscription committees were in big towns.

[Page 154]

It was possible to pretend if you wished. Some commissions in several cities had a good name. That is to say, the commission doctors took some bribes and gave a yellow or even a white ticket. To get a good ticket, there was a need to have a defect. There were good defects which you could easily get a white ticket, and not so good defects, which you could get a yellow ticket.

A very good defect was, for instance, to have heart disease. A young man with heart disease could really brag. A crooked foot and a hand with a missing finger were also very good and made the draftees and their families happy.

Another good imperfection was to reduce weight: people ate only thin crackers and snacked seeds to get thinner and lose weight. A man under a specific given minimum weight was not drafted.

A light defect that could be of a good use if the doctor was bribed was called (according to the law paragraph) a “sixty-six,” or in common language, a hernia.

In the villages, there were defect-makers, real specialists. They could “make” heart disease, a swollen foot, a twisted hand, cut a finger, and especially make a sixty-six very easily. The guy with the sixty-six had to get used to it and develop the defect. For instance: jump from a high table, lift heavy weights, etc… Those who pretended were satisfied, receiving compliments. People with other types of defects, especially the “sixty-sixer,” loved to exaggerate about their defects.

I remember a conversation between my father and a neighbor. My father pretended he had heart disease and ate salty rolls, so his heart, G-d forbid, would not lose its defect, which was an irregular pulse. The neighbor used to jump all the time, day and night (we could hear it through the wall) from the counter of his shop, in order to inflate and pretend to be a sixty-six. One day he swaggered to my father:

- “Moshke, have a look at my sixty-six, touch wood, it plays well and grows, looking good.”- “No jealous one should ruin it,” answered my father like he was an expert.

And the neighbor's wife was jubilant about her husband's “treasury” and added:

- “I thank you, Master of the Universe, tfu, tfu, tfu[2], for your kindness, should the jealous ones burst from envy.”

[Page 155]

The ones that were deserters

Some people did not pretend to have a disease. They just did not show up for the conscription. They were hiding, and we called them little hare (hozlech). They made themselves as if little hare.

Occasionally, hare catchers came to the shtetl. They were called little coat peltzlech, presumably because of their uncovered short pajama coat peltz-pizhaklech. Why did the secret little hare catchers need to wear short coats to be detected? Who can understand the logic of the Tsarist police?

As soon as the rumor spread out that the little hare catchers are coming, each deserter ran to a second one, telling him that they must hide. They took a sled and ran away to another shtetl. In these times there was a characteristic song which I remember only a few words:

And when somebody got into the military service, these were in the majority, stupid people, who were not looked after, and poor people. We always wished him that he should fall in captivity by the Germans. Because by the Germans it is a good captivity. When a family received a notice that his soldier was taken in captivity, they used to rejoice: on Shabbat, they invited people to a Kiddush in their home, and in the house of study they handed out cakes and liquors.

A lot of soldiers used to teach one another how to fall into captivity, being often of great danger as to be considered as a deserter. Linked to that, we used to tell the story of a new Jewish soldier, who on his first day on the front, asked:

- “Where can I find here how to fall in captivity?”

Once a non-Jew came to visit us, he was a Tsarist soldier and succeeded to escape from German captivity and came back to his unit on the front. Jews burst out laughing from the “Goyim's head,” the idiotic sub-Ivan[3] who escaped from captivity.

A Jewish prisoner of war by the Austrian told a bad but amazing story about the Austrian Jewish soldiers who escaped the Russian captivity like the Goyim.

[Page 156]

- “Kyra[4] tales”

The Austrian Jews were described with the word Kyra because they used to call their Kaiser Franz-Joseph with high esteem: His Emperor Highness. Russian Jews used to mock their foolishness.

In winter 1916-17 Russian garrison came to Yedinitz. The soldiers were accommodated in Jewish houses. These Russian soldiers, sons of peasants, were of good disposition and did all kinds of work: chop wood, lit a fire in the heating stove, brought water, played with the children, produced all kinds of carvings. All day long they brought boiling water (kipiatok) in a small kettle and drank tea. From time to time they got drunk.

On a certain day, whether a Shabbat or Sunday, came, a gang of soldiers and raided the wine cellars and swallowed the wine. Other ones took out the wine barrels and spilled the wine in the culvert. Soldiers bent down to the wine stream and gulped until they lost their senses. Except for this, I don't remember that they made any trouble. Non-Jewish girls used to avoid them.

I remember once that a Cossack section on their way stopped on the Patchova Street. We, the children ran to see them. We also saw that non-Jewish people from the city council avoided the Cossacks. Some gentiles took individual Cossacks to a farmhouse to “lie around” on a bench or the ground with a gentile girl. One Cossack did it in front of everybody on a bench across the Shaarei Tzion synagogue. The nearby Jews shouted at us:

– “Go away, rascals. There is nothing to see, do you know how the Cossacks are? You could trigger murder and bring misfortune on Jews, go away.”

The Cossacks left and between the non-Jewish guys and girls a scuffle started: they could not agree on how to split the money.

Translator's footnotes:

Translated from the Yiddish by Asher Szmulewicz

| When the February revolution broke out, the news came to Yedinitz a few days later. Young people said the Tsar Nicholas was deposed, and the cautious Jews were afraid and asked for silence: |

[Page 157]

| “Hush! We can't know it yet.” |

The town's residents attended meetings where speeches were made about the Tsar. I can still remember people shouting “Hurrah” and “Down with the Tsar.” There was a sense of freedom around us. At the demonstrations there were many people waving flags of Zionists and Socialists. Later, the Bolsheviks also demonstrated. There were protests against pogroms and against Goyims who attacked Jewish landowners. The Jews had bitter experiences of popular wrath. We heard mere gunshots from non-disciplined soldiers. They took their loaded guns to go shopping, hoping they would scare the shop keepers into selling merchandise for a pittance. The former soldiers would test their guns by shooting into the air.

There were cries about the Romanians who wanted to take back Bessarabia. A bizarre young man named Victor came into the shtetl and turned around the community affairs. He was from Romania. We suspected he was a Romanian agent. He wanted to immediately create a self-defense squad, the sumo-oborone.

During that time, the front got nearer to us. The peasants ambushed and looted the landowner's “court” in the “manor.” The Goyim from the villages around us became brazen towards Jews, especially against the prices of the goods sold in their shops.

One Thursday night, we heard shooting. It was a pogrom. We hid what we could. My father had left some goods in the shop on purpose so that they will have something to loot. We extinguished the wick of the lamps and waited. From far away we heard knocking. Shops were broken open and the goods were dragged outside. Close to our home, the shoe shop Obovne, of Nissel Kolker, was broken into. The Goyim took whatever they could: shoes and overshoes, shawls, and overcoats, shouting in Wallachian. I still remember it today: “You will still ask for five rubles for a pair of galoshes?”

We heard knocking on our door. My father went to open it, but a few Goyim broke in using iron bars. They may have been soldiers. My father started to implore that he was poor and had children, but something in our apartment and his shop displeased them. They dragged a few pieces of goods from the emptied shelves. A Goy burst into our apartment and took away the two candlesticks from the dresser, threw them in a bag, and ran away. When the Goyim left our apartment we breathed again; we were lucky. We thanked G-d for his mercy.

[Page 158]

Suddenly there was an uproar, fire! The pogrom participants set fire to the shops on the lower Taravitse Street. We ran to douse the fire. Jews shivered. Jewesses wept into their hands. There was a rumor that we should not put out the fire. We thought the Goyim wanted to set the whole shtetl on fire.

In my childish brain, the fire and the pogrom looked as if the whole Jewish world was burning. I remember I asked my father and said: “Once the land of Israel was burning and we went to exile, today the exile is burning, so we will go to the Land of Israel.” Nobody listened to the children's chatter, rightfully stuffed in our heads by the outstanding teacher Dubrow.

The fire disbanded the pogrom participants. The soldiers left, too. The Goyim loaded the bags on their carts and went back to their neighborhoods in their villages. In the morning we saw the Jewish belongings scattered in the street, how doors and windows from Jewish houses and shops were broken, and that Taravitse Street was burned out.

The Jews asked themselves: “What should we do?” As usual, nothing was done. People went to the military commander. He promised to do something. On Friday evening, another pogrom started. Even more Goyim came from the nearby villages with bags, again gangs of soldiers, and Goyim from our shtetl. They went from house to house and looted. From the lower Yedinitz narrow streets came rumors the Goyim were also beating Jews. There was not a second fire set.

During Shabbat morning, we had the same images as the day before.

“Something has to be done.” Here I remember how Victor arrived. He organized a self-defense squad. In the “Zemski Oprave” (a city council) there were a few guns and additional guns and pistols among some Jews. The guns were shared with former soldiers who were posted at the shtetl entrance. A few young guys took rods. Other young men were asked to make noise banging rods on metal plates as if they were drums. The guns were fired and the rods banging on the metal plates made a noise. Here and there we left the samovars filled the entire night so our fighters could warm up themselves with a glass of tea.

[Page 159]

Victor ran from one position to another, asking them to “drum.” Also, another young man called Berezin was active and knew self-defense.

During the night between Saturday and Sunday, the pogromists could not enter the shtetl. They waited in their carts with their bags close to the entrance road.

The soldiers arrived Sunday morning. I think it was the Cossacks, and the Goyim came in with them. The soldiers came in to catch the “rioters.” Victor disappeared. Again, there was a pogrom, and the Goyim filled up their bags. There was turmoil. Jews came out in the streets and lamented. I don't remember exactly what happened. Jews packed their bedding and carts they rented from Goyim who came looting. Where should we go? Who knows? My father also rented a cart, loaded bundles, my mother took my little sister Sarah in her hands, and my father took me.

I don't know why, but we left the cart and came back home. In the afternoon, the soldiers and the Goyim left the shtetl. In the evening, there was not a pogrom. I believe a delegation went to Brichany, where there was a more important military headquarters. The next day, soldiers came to guard the shtetl against further pogroms.

Somebody ordered to scatter the torn items in the streets to make the Jews look pitiful to the arriving soldiers. The soldiers were greeted by weeping Jews who offered them tea and cigarettes. Boiled water was prepared at several locations for the guards and snuffboxes of tobacco were prepared. Due to the kindness of the new guards, there were a lot of stories floating around. We had to beg them to accept cigarettes and money. Then these guards accepted our gifts.

There were no more pogroms. Jews bought more and more guns, revolvers, holsters, and weapons. People were fed up with the “Freedom.” We heard that in Kishinev the landowners set up a parliament and wanted to remove Bessarabia from Russia and they asked the Romanians to come in. The Romanians were already not far away.

[Page 160]

Translated from the Yiddish by Pamela Russ

| Suddenly, they (the Jews) saw that the Russian soldiers left the city. Some Romanian riders tore through Patchova (Postal) Street and then quickly left. The Jews formed a delegation, set themselves up at the bridge to wait for the Romanians, and greet them with bread and salt. Young boys climbed up trees and hills to see them as they would arrive… |

They arrived … at first, came riders on horseback. They broke up the Jewish delegation and immediately called out: “Stare de asedow” – “Osadne polozhenie” (Russian term “in a position of siege”) and told them to get rid of all the weapons that they had with them.

Rumors spread as to why the Romanians had tied red ribbons to the tails of their horses.

“This is a type of sign showing that they have “freedom in the behind.” This was the Russian Revolution that was called “freedom – liberty in the bottom parts.”

The Romanian soldiers looked pathetic. Their clothes were torn, shredded, many of them were practically barefoot. Their main food was mamaliga (cornmeal porridge). But they instilled a terror into the civilian population, putting out all kinds of underhanded orders. They shot Jews and Christians, but mainly, beat people for every past or not past sin:

“Five beatings on the backside, ten on the backside, 25 on the back, and even more.”

All these horrible stories are written up in the book.

The Romanian powers positioned themselves in Yedinitz and did not leave. The border was five kilometers away from the town. Across this border, in the village of Glinoje (Hlinaia), on the way to Brichany, the “Germans” already ruled. From the town of Brichany, 25 verst [Russian measurement of length, about 0.66 mile] away exceptionally wonderful reports came about the regime of the “Germans,” which in reality was the Austrian military.

By us, the Romanians kept shooting and shooting. Behind the Germans, there was “a life.” People did business and continued working. The Germans respected the civilian population. There, people began a smuggling route, from here to there and there to here.

[Page 161]

The Jews began to long for the Germans. And if one desires something, then, he begins to hear the rumors:

“Here they come! They're coming tomorrow! Someone just saw that the Romanians are packing up.”

One spring day, there was a joyful uproar: “The Germans are coming!”

From Patchova Street, you could see that “behind the willow trees” there stretched a military line, with soldiers dressed fancy in colorful uniforms. In short, “Germans.” Why did the Romanians not leave?

The line came up from the road near the seminary on Patchova. Generally, not looking like victorious troops, they were moving slowly. The Jews stood at a distance to see what was going to happen.

But one Jew with a fire red beard, tore out of the crowd, ran over to the rider who seemed to be the “senior,” began to embrace him, even kissed him, and began shouting and crying in Yiddish that sounded like German:

“Thank God that you came. We can't tolerate the black Romanians, the gypsies, any longer. You are our saviors.” To everyone's surprise, the “senior” shoved away the Jew with the red beard, and the line of soldiers continued riding up Patchova and stopped near the Romanian command headquarters. There, the “senior” dismounted and then reported the sad news to the Romanian commander, the sadly famous Major Dimitriv, that when they arrived in town a Jew with a red beard greeted them as “Germans, redeemers from the Romanian gypsies.”

Who were these military, polished soldiers in colorful uniforms? Today I would say, operetta-like uniforms! We found out these were the leftover soldiers from a Polish unit that suffered a defeat in Ukraine and that saved themselves by crossing the Dniester River, in the territory that was under the Romanians.

The Romanian government sent out guards immediately to grab up the traitor, the “Jew with the red beard.” Who that red-bearded Jew was, remained a mystery to me until today. But the Romanians made this easy for themselves. They placed under arrest all Jews with red beards, and red Jews without beards, and Jews with beards, not even red ones.

The Polish “senior” had to recognize the one they found, the Jew with the red beard. But among all the tens of Jews that were captured, he could not recognize the guilty one.

[Page 162]

However, the Romanian commandant could not allow himself just to leave the captured Jews with nothing, so all of them were taken out to the cowshed, had to pull their pants down, put themselves on all fours face down, and the beatings began. The younger ones got 25 beatings on their behind, the older ones only 10 or 15 lashes.

An elderly Jew, who was living near us, had a fiery yellow-red beard. His name was Shmuel Niamtz because he came from Galicia-Austria and spoke with those jargons. He was about 80 years old and barely dragged his feet. He was also arrested and received four thrashes to his behind. If they would have given him a fifth, it would have done him in. They carried him home. He could not sit for weeks nor sleep on his back.

The end was, that the “Germans” left northern Bessarabia and Bukovina and the Romanians took over the territory. For many years, the Jews of that area spoke of the wonders of the brief German rule with great yearning.

The Romanian rule adjusted itself. Even the Jews were happy because there was a civil war, hunger, and pogroms across the Dniester, and Jewish refugees from Ukraine began to come over from there.

People began to become accustomed to the Romanian regime. The city acquired a status of a community, secured a “premier” status, and Jews were identified or voted as “premiers” (first-class citizens). Premiers changed themselves by changing their party (loyalties) in the government. Yedinitz, as all of Bessarabia, did not experience great development under the Romanian regime.

Jewish Life

Jewish life evolved confidently, independent of general life. All the Zionist parties arose. In the elections of the last three Zionist Congresses, Yedinitz voted with close to 700 members. The list of workers in Israel contained over 400 voices. Leftist elements heard from or sympathized with the underground Communist movements. Young boys and girls joined the “Hachshara” (groups for “preparation” for life in Israel) of the Hechalutz (youth preparing agricultural skills for living in Israel), and then made Aliyah. Hundreds of youths immigrated to South America to earn money.

[Page 163]

Some of the youth went to the larger cities for work. Others went to study, some as teachers in the Hebrew seminaries, and some to the universities. The local gymnasium (secondary school) that started with Hebrew, became Romanticized, and finally lost its status and shut down.

In the 1930s, a crisis broke out. Earning a living became even more difficult and the youth had nothing to do. The intellectual and active energies left town.

The government's persecutions against the “Communists” did not permit any cultural activity.

The local non-Jewish youth, even the sons of the gypsies, who used to mingle with the Jewish youth and was even able to speak Yiddish, joined the Kuzist party (right-wing, national Christian party); later, during Hitler's times, these were the most vicious murderers of the Jews.

The students and teachers of the priests' seminary were agents of anti-Jewish incitement. Towards the end of the 1920s, the seminary members tried to direct a pogrom against the Jews. There were fights between them and the Jewish students in the gymnasium; the priest Zharzheski, director of the seminary, became one of the main Kuzist agitators (he later went over to Codreanu's Iron Guard, and symbolically called himself “Preotul (priest) Zharzhescu – Yedinitz.”

Then the Kuza-Goga regime arose. Romania became an openly fascist country. The air became constricted. Everyone was envious of the person who was able to save himself and leave the city. This was characteristic not only of Yedinitz.

During the years 1929-1938, I stayed in Czernowitz, where I studied in university, worked in the Poalei Tziyon Party (later the United Zionist Socialist Party Poalei Tziyon – Tzeirei Tziyon), in the youth movement Dror in Hechalutz, and edited the party newspapers “Arbeiter Zeitung” (“Workers' Newspaper”), and “Aufbau” (“Building”). For some time, I was also a correspondent for the Kishinev [Chi?inãu] “Unzer Zeit” (“Our Times”), and the Bucharest Romanian Jewish and party organizations.

The Kuza-Goga regime shut down all the newspapers and organizations.

In 1938, I immigrated to Israel. After that, came the year 1939, the war, the Russian occupation of Bessarabia; the Russo-German war in 1941. Romania came back to Bessarabia; Transnistria was destroyed, destroyed. The ones who write, are the ones who bear witness to the destruction and downfall of Yedinitz as a Jewish city.

[Page 164]

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Edineţ, Moldova

Edineţ, Moldova

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 16 Jun 2022 by LA