|

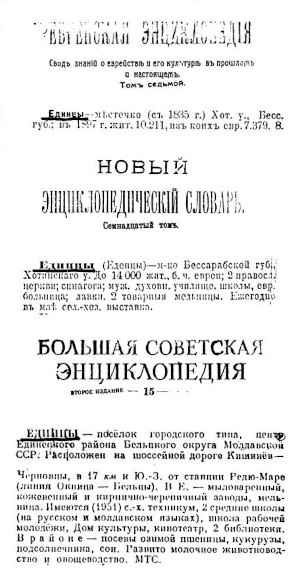

Below: “The Grand Soviet Encyclopedia,” Second Edition from 1951. Volume 15.

[Pages 33-34]

|

by Yosef Magen-Shitz

Translated from the Hebrew by Mary Jane Shubow and Asher Szmulewicz

The editors of this book have struggled considerably with the issue of how to spell the town's name. In Yiddish, should it be written Yadinetz, Yedinetz, Yedintzy, Yedintz, or Yedinetz? And how should it be written in Hebrew? Finally, it was decided to write יעדינעץ Yedinetz in Yiddish and ידיניץ in Hebrew. Both are close to the way the name was pronounced by its Jews. The exact source of the name is unknown. Everything said on the subject is nothing but assumptions and guesses with no real basis. It is assumed the name was taken from the Russian (or Ukrainian) word “yedinetz” (the lonely, the only). From this, we learn that before the settlement received official status there were lone houses or residents in a place that had no name at all. The residents themselves, or their neighbors, called the growing settlement by the name of “Yadintzy” by themselves (houses or residents) so that was what the new Russian authority in Bessarabia called the settlement.

In Russian they wrote the name of the settlement Единцы, but the concept “residents of the town” was pronounced Единицей (in the plural Единчане). The “goyim” who spoke “goyish” or 'Chaclatzky” (as the Jews would say), who called themselves by the name “Rusantzky” (their dialect was like Ukrainian), pronounced the name of the town “Yedinatz”: as did the Moldavians, as well in their language, like the Jews.

When the Romanian people arrived in the town (in 1918) they had no uniform way to transcribe the name. I remember that the Romanians wrote the name like this: Edinita, Ediniti, Edinet, Edint, Edinti, Edineta, Yadinitza, Yadinitzi, Yadinetz, Yadinitzi, Yadintz, Yadintza, etc.

The fact that the Romanians did not have an old name of their own for the town (they did have their own old names for other settlements in Bessarabia), is further proof that the settlement was only founded after Bessarabia was annexed to Russia (1812)

The settlement does not excel much in history after that, not in general and not Jewishly. In “The Jewish Encyclopedia in Russian” published in Petrograd in 1909, it is written that the settlement “Yidintzi” received the status of “Miastechka” (town) only in 1835.

The lands of the town belonged to the paritzim (landowners) who lived far away: the Kozitzkin and Kazimir families. The latter were of Polish and Catholic descent.

[Page 36]

During the heyday of the previous century, and the beginning of the current century, they founded all kinds of institutions in the town: an elementary school, a tea house, and a town hall (the Gymnasium was situated there during the Romanian regime, and recently, a Jewish home for the elderly). They founded the Agricultural Exhibition (which was eliminated under the Romanian regime), planted the municipal garden (the “Boulevard”), and for themselves, they planted a fruit-tree garden that was generously cultivated (called the “Ausiadva” by the residents). Within it, they established a residential “palace.”

At the beginning of the 1930s the writer of these lines visited together with a friend from my youth, Israel Kolkar (currently of Lviv), the old Jewish cemetery. After many searches we found the oldest gravestone and the date of death engraved upon it was the year 1821.

This led me to conclude that the beginning of the settlement was at the beginning of the 19th century. Given that the names of most of the towns and villages in the area are Moldavian, and a few of the place names are of Slavic origin (including Yedinitz), and that Bessarabia fell into the possession of the Russian government only in 1812, we must accept the assumption that “the settlement of those who are by themselves” was only established after the Russian conquest by Russian or Ukrainian speakers. Hence, its Russian name. It seems, that there were Jews among the first settlers who were “by themselves.” The clearest sign of this fact is the Jewish headstone from 1821. However, from the outset, the Jews were few, as we shall see.

Unfortunately, there is no way to search any archives.

[Page 37]

Who knows if any archives were even preserved to describe the history of the town and its Jews?

I found something about the town recorded in three encyclopedias in my possession: “The Russian Jewish Encyclopedia” of 1901, which I mentioned above, “The New Encyclopedia” from the end of the 19th century, and the “Great Soviet Encyclopedia,” Second Edition, that began to appear after 1950.

And here is the entry “Yidinitzi” in “The Russian-Jewish Encyclopedia”: “A municipality (since 1835), Hotin district Bessarabia Gubernia in 1897, the general number of residents 10,211 of whom 7,379 are Jews.” The encyclopedia is based on the census taken in Russia in 1897. In that year, this encyclopedia states in another article that 307,532 people resided in all the Hotin district, amongst them 48,000 Jews (close to 16%!). The city of Hotin had a population of over 18,000, amongst them 9,291 Jews (over 50%!), and here are the census figures of the settlements inhabited by no less than 500 residents.

Name Total Jews Ataki (Otek) 831 123 Balboka 829 84 Briceni 7446 7184 Balashkova 1050 119 Yedinitz 10211 7379 Klishkotz 7707 1000 Lipcani 6865 4410 Neparakova 1631 268 Navoselitz 5891 3898 Rebovnitzi 2140 369 Securan 8982 5042 Tchepleotz 1555 163

What do these numbers teach us? Already by the end of the 19th century, Yedinitz was the second largest town in the district after Hotin, both for the general population as well for the number of Jewish residents. After Yedinitz, came Briceni (the most Jewish town in the district!), Securan, Lipcani, and Novoselitz.

In 1897, the first modern general population census that counted the number of individuals was conducted. Before that only “families” were written down.

A previous census took place in Bessarabia in 1847: It was called “Revision.” The “Jewish Encyclopedia” records the following numbers for “Jewish Communities” which just refers to the Jewish population because there were no organized Jewish communities. A table for the Hotin area, according to the revision of 1847, is below:

In Hotin itself: 1067 families Lipcani 713 families Novoselitz 81 families Briceni 602 families

[Page 38]

|

|

Below: “The Grand Soviet Encyclopedia,” Second Edition from 1951. Volume 15. |

[Page 39]

Yedinitz is not mentioned in this table, nor is Securan. Apparently, there were in Yedinitz at that time less than 81 families, which were listed in Novoselitz and we must not forget that already in 1835 Yedinitz received municipal status.

The general population, and particularly the Jewish population of Yedinitz, sprung up in the 50 years between the first count, the “Revision” of 1847 and the census of 1897.

What is the reason for this growth? It is incomprehensible to me. The shtetl was not situated beside a large highway, had no industry, certainly no rich natural resources, and was generally off the beaten track. Perhaps the growth stems from the large agricultural space of which Yedinitz was at the center.

From whence did the Yedinitz Jews come? According to “names” by which the Jews were called: Terebener, Risener, Zabrichener, etc., many came from the surrounding far and near villages. Some came from Ukraine, from across the Dniester.

In the 18th century most of the Jews lived in the villages. In the 19th century many Jews left the villages and settled mainly in shtetls and villages. This process increased during the Romanian rule, after 1918. After the Shoah, hardly any Jews were to be found in the Bessarabian villages.

And there is another interesting point that concerns the shtetl in the last years of the previous century. In old Romania one person by the name of Zamfir Arbore, a Bessarabian with a “nationalistic-Romanian” consciousness, who, it appears, ran away from czarist rule in Bessarabia, at that time Romania (Regat), had a book published in a geographical lexicon format. In his book, Arbore listed all the settlements in Bessarabia in which he included some historical and geographical facts to the extent of which he was aware. But in this book, there are no details about the founding of Yedinitz. He writes the name of the shtetl in a unique name: EDINTA (Yedintza). Conclusion: This is another proof that there was no Romanian spelling tradition for the name of the shtetl.

The above-mentioned author “knows” to convey the following dates regarding “Yedintza.” Total population 3450 of these 1242 Russians. In the shtetl, there are approximately 670 houses. That's it. Who are the “Russians” and who are the other 2208 residents? This he doesn't tell us. Nor does he say when (year or epoch) these residents lived there. As stated, it apparently deals with the end of the 19th century. We can't be enlightened by the above-mentioned work of Arbore's book of numbers and dates.

And another Romanian source:

The Romanian sociologist Victor Tufesko released a research paper about the “Moldavian Shtetlach and Their Economic Importance.”

The writer wants to show that the Jewish shtetlachs are a “foreign body” in the agrarian-Romanian district. He states that the shtetlach were partially founded at the end of the 18th century, but mostly in the 19th century. He adds historical and demographic particulars about the shtetlach which he mentions. He apparently relied on reliable sources. This is what he tells about Yedinitz:

“Yedinitz (Hotin). A shtetl was founded in 1820. In 1930 it had 5625 residents of whom 5354 were Jews. There was a weekly fair, an oil factory, etc.”

The year it was founded (that is to say, reorganized as a stable settlement), in 1820, is the same date as we have previously encountered. The writer has repeated these many errors, where it appears as though there were two different settlements – the “town” and the “village.” He only gives statistics for Yedinitz “berg” (town).

[Page 40]

|

|

Incidentally, the research appeared in 1942 when the Jewish shtetl of Bessarabia, Bukovina, Transylvania, and Norah-Moldova was destroyed and the Jews had been expelled, and many murdered. The researcher justifies this calculation, though his research was unnecessary.

The Romanians, during their rule in Bessarabia, conducted only one census, but in that period existed an administrative municipal division for both parts of greater Yedinitz – “Yedinitz town” and Yedinitz village.” And this is what that census gives in its official publications.

In the shtetl-Yedinitz (targ) there was a total population of 5910. Of these, according to their ethnic roots:

Jews 5341 Romanians 194 Russians 344

But according to “religious affiliation” the following figures are given:

Mosaic religion 5349, which means that only 5328 people (Jews) declared that their spoken language is Yiddish. That means, that eight Jews declared themselves as such from a religious standpoint and not from an ethnic-national standpoint. Twenty-one Jews declared that Yiddish is not their daily spoken language but rather Russian or Romanian. Factually, a small percentage of assimilated exceptions. Or maybe, we have here a mistake in the registration and here are the results of the non-Jewish part of the settlement in the Yedinitz village. The total number of residents: 5260, amongst them:

[Page 41]

According to the “ethnic roots” 398 According to the Mosaic roots 401 Yiddish speakers 401

The other residents (the majority Christians) are listed according to their nationality:

Romanians 2183

There are the Moldavians. The true Romanians from the Ragat and the gypsies who declared themselves as Romanians.

Russians 2214

(Including the “Katzapes” and part of the “Chachlahzki”speaking. The true “Russians,” whom the Jews called “Christians” in contrast to those who spoke Ukrainian dialects. These, the Jews called “goyim”).

Ukrainians 353

Germans 3

Who are they? Perhaps the remainder of the Ehrlich family, true Germans who lived peacefully amongst Jews? Or maybe the convert Yohan Kaufman's family who became Lutherans, registered as “Germans?”

From the religious standpoint, the Christians from the “village” registered as follows:

Orthodox 3792

Actually all Christians except:

Katzapes (Lipovener, Staro-Vertzi) 1014.

In total, lived there at that time in all Yedinitz, both in the “shtetl” and the “village,” 11,170 people, less than was previously thought. This included 5150 Jews -330 more than non-Jews (5420). That is to say, that in 1930 there were in the whole shtetl only 59 people more than in 1897 (10,211!). The number of Jews in 1930 (5750) was reduced by 1629 from 1897 (7379). The difference between the number of Jews and the number of Christians that was in 1897 (2832), more than Jews in contrast to 1930 (5750) which declined by 1629 from the year 1897 (7379). The difference in numbers was even greater between the number of Jews and Christians which was recorded in 1897 (2832 more Jews) as opposed to 1930 (only 330 more Jews). Percentage wise: In 1897 the Jewish population was over half of the total population, 72%; in 1930, the percentage of Jews fell to 51%.

As far as I remember, there were in Yedinitz at the beginning of the thirties (I worked for a short time in the "Primaria" then), approximately 3000 houses, and in more than half of them, Jews lived. It was believed at that time, that there were around 15,000 in the shtetl of whom more than half were Jews, and roughly a smaller portion of Christians. The 1930 general census has different numbers. As we see, the Jewish population did not grow but rather declined in Yedinitz since 1897 (7379 Jews!) meanwhile the Christian population grew, nearly doubling.

The main reason for the slowed-down growth process of the Jewish population of Yedinitz after 1897 is the emigration to overseas to North and South America, where there are more than 1000 stemming from Yedinitz. Tens of Jews emigrated to Palestine. Only a few hundred moved to other cities in Russia, or later, to Romania. Only after the Shoah hundreds of Jews from Yedinitz emigrated to Eretz Israel.

And now let us make a further leap to the "Bolshoi Sovietski Encyclopedia,” Second Edition. In Volume 15 (published in 1952) we find the following about Yedinitzi:

[Page 42]

|

How many Jews were in Yedinitz? The old-timer Yedinitz Jew, Mr. Shmuel Kormansky (Tel-Aviv), who is above 80 years old (till 120 years), claims that it was not difficult to compute the number of Jews in town. You just had to calculate the “Kwitels” (receipts) for the Kaparot sold on Yom Kippur eve. After all, no Jewish family,” G-d forbid, would be kept without Kaparot. |

“A settlement of the city kind. The center of “Yedinitzi region” Yedinitz region (Beltz district) in the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic is located close to the railway line Kishinev – Czernowitz, 17 kilometers south-west of the train station Radio-Mara (line from Oknitza-Beltz). There are small factories in Yedinitz, of soap, leather, bricks, a mill, schools in 1951, an agricultural technical school, two secondary schools (languages of instruction Russian and Moldavian), a school for the working youth, cultural centers, cinemas, two libraries. Wheat grows in the region, also corn, sunflower, and soybeans. Milk production is also developed. Cattle and sheep are raised.

There are no national composition figures of the population.

Since the Soviet regime returned to Yedinitz we don't have details of the population census. This is of no importance. According to the remaining nowadays Jews in town, only a few hundred Jews are living there. A hundred more or less does not change our conclusions.

The last “shochet” and Rav, Reb Yeshayahu Elkis, who made Aliyah to Israel in 1972, reports that in Yedinitz were gathered in the period of the Soviet rule 300 Jewish families. (See interview with him in this book.)

Where are the Yedinitzer survivors now after the catastrophe?

According to a rough reckoning, that is, in my opinion, close to the reality, there now live:

In Israel, 600 Yedinitzers

In North and South America, 1000 Yedinitzers

In other lands, 200 Yedinitzers

In Russia and Romania, 200 Yedinitzers

In Yedinitz itself 300 families

Approximately 5000 people perished in pogroms during the Romanian-German invasion in 1941 and in their wandering during their deportation to the death camps of Transnistria. May their memory be blessed!

|

|

By Pinchas Man-Meidelman

| Donated by Elizabeth Schindler Johnson and Catherine Schindler and dedicated to the memory of their mother, Roslyn Needelman Schindler, their grandfather, Henry Needelman (b. 1902 in Yedinitz, Bessarabia, as Chanany Nuedelman) and to his brothers and sister, Louis, Herman, and Fannie, who also emigrated to America, and to all of the unknown family members who perished in the Holocaust. |

| Childhood and homeland! There's really no difference It's she that's the seed for wide horizons And she is the center of the universe That's why it's no wonder, let's publicly say. That we all – why should we deny it? Carry deep in the hidden chambers of our heart, Forever and always the city of our childhood. |

| By Shimshon Meltzer |

Memories – What for!

At first glance the words seem right of that shtetl-nostalgia-enemy that argued. What do we have in common with that out-of-the-way shtetl, whose way of life we were so fond of and that we left without longing?

It appears that there is much truth in this argument, that the youth who left the shtetlach in Eastern Europe years ago, led by a strong national feeling, a vision of the future, has no grounds for nostalgia for the past. Their direction in life is a result of uprising and struggle against the past and against what awaited them there.

Furthermore, ever since they planted themselves in the Land of Israel, they managed to have a very full life being witnesses to wonderful and colossal changes to which they themselves contributed.

[Page 44]

Now the citizens are in a free and sovereign State. The majority raised families and their children live far from the disastrous events that their parents lived through in their childhood and youth.

The boys and girls of yesterday, it's true, have in the intervening years grown grey and lost much hair, but biological changes alone aren't sufficient reason to clamor into the past.

We must not forget, however, that only once in the history of mankind was there “Braishit” (The Beginning) and from then on there exists a steady connection in the historical process; also the sharpest changes in the individual's life and of the masses, have their roots deep in the social and spiritual weave of the community in which the changes began. One cannot understand them, therefore, without knowing the faces and the background that existed before those changes took place.

Furthermore, we are living in a generation that is swiftly moving forward, true, there is an interest in Middle Age archeology but to mock the graves that were but yesterday dug, are the later not entitled that we should halt there for a moment to tell them that there was once life here? Maybe the gravestones that we are erecting are not monumental, but small and at times provincial, like the shtetlach from which we sprouted, but they are also intimate and individual so that they enable us to unite with relatives, friends and chaverim from whom we have parted forever. The self-confirming eternity is the thread that connects us.

Aroma of Gardens, The Spirit of the Shtetl, and the Fearful Bells

Translated from the Hebrew by Naomi Gal

The steppes stretched all-around town and behind some houses was the apple orchard of Zhilovky. In the Spring everything bloomed and the plants showed their many colors and wonderful fragrances. There were orchards of apples, pears, cherries, and plums. Birds sang, and the meadows were green in the summer months. In the sea of autumn gold, a wind blew and spread out into the surrounding forests. In winter, there was sleigh riding on a horse-drawn sled with two horses speeding along in an all-white world under the moonlight.

But despite of the wonderful landscape, Yedinitz was one of the most out-of-the-way places in a far-off province that “sits” on the border of two nations.

When it came to traffic and communication, the town was frozen, like living in medieval times. The closest train station was 18 kilometers away and there was not one decent paved road that connected the town to its surroundings. You always knew when you left on your way but never knew when you would arrive especially during the rainy fall months and in Spring, when the snow melted and the roads became a drowning swamp, where the horses sunk in the mud harnessed to the “carriages” reaching to their stomachs. This was a place where the blood arteries through which flew the communication with the world were quite ineffective.

While disconnected and isolated from the world, the town endured an economical and spiritual crisis in the forceps of both world Wars, which determined its final fate.

The pastoral exterior of the town did not always match its inner landscape. The real panorama was, alongside with the eight synagogues standing locked and deserted at the edge of town, down the hill, and in their center where stood the unfinished, two-storied, spacious “Shul” made of red bricks, the all-around darkness and poverty. For sure, here was once upon a time a center of Torah, faith, and man's prayer. Time had passed since the poet sang: “There are still extinct towns in the diaspora, where our old candle smokes in secret.” Here, no one was left, and the place inflamed only children's imagination with spirits and demons and midnight lamentations of the Temple's destruction – and death. On the other hand, at the center of the Jewish town, anxious and frightened Goyim built their own cloister, high, bright, and shining with its steeples and numerous crosses. They brought here their living and their dead and rang the alarming bells into the confused town. On cold, snowy days, flocks of black ravens found a haven on the church's high campaniles and from there descended on the town with deafening screams – they harbinger evil only, only evil.

The Gendarme's Regime

Under the influence of transfer from one regime to another, accompanied by an inner economical and spiritual crisis, I lived the town's life for several years between the two World Wars.

[Page 46]

When Bessarabia fell into Romanians' hands, two factors determined the treatment of the authorities towards Bessarabia's Jews in general and the fate of small towns in particular:

These two factors affected the town's life from the very beginning of the occupation. The persecutions and harassment harmed the town's inhabitant's way of life before antisemitism celebrated its official victory in the country.

The small towns were practically under military regime throughout all the Romanian rule and Yedinitz was maybe more so than any other town; it was the playground for outbursts of dark, sadistic impulses. The town was exclusively under the government of the brute gendarme, the “Chef de Post,” who was sort of an only ruler with all the residents prone to his grace or wrath. He made the law and was the judge and the executor while his mental state and the number of glasses of alcohol he consumed had a crucial impact on the well-being and safety of the town's people. The “Chef de Post” was in charge of the town's morale and its economy. He controlled its social life and culture. He was the one deciding about meetings or canceling them, and also dispersing meetings to which he consented; he was the one determining theater shows and evenings' entertainments, and locked people up and released them. He was everything.

To this day, I see the frightening pictures of Shabbat's nights when most of the young and adults came out strolling leisurely on “Patchova,” the main, long street, and the nicest in town. The “Patchova” was the only place for entertainment (the authorities managed to destroy the boulevard, probably assuming it harms the public's heath). This was the meeting place for young men and women. This is where you saw the latest fashion. Here while strolling, a first love bloomed. And here, ideas were exchanged on politics and about the new book borrowed from the “bibliotheca,” the library. And it so happened that the “Chef de Post” came out drunk and sulking and screamed in a high-pitched murderous voice – “everybody home! (Toata lumea acasa!) and everyone, like frightened sheep, scattered into side streets.

Yes, he was a “Supreme King” who ruled exclusively the town's unprotected, helpless citizens.

Concerns of the Youth About their Future

As outside pressures of a hostile administration on the town became tighter and tighter trying to uproot all joys of life by using an economical straitjacket accompanied by heavy imposing taxes intending to undermine the physical life of the town, the town was caught in a social and spiritual crisis; its signs being the crumbling of the traditional Jewish life at home and outside.

[Page 47]

The known idyll when young men and women get married and build their home next to the family nest dissipated forever when the parent's livelihood was disintegrating and it was no longer possible to incorporate sons and sons-in-law in the parents' upkeep, not in commerce nor in labor.

Inside the homes grew the gap between traditional parents tied to past customs and entrenched in their beliefs, and their sons who felt the earth shake under their feet and wondered about their way of life and their future.

The feeling most of the youngsters shared was that here in this town the way things were happening meant that they had no future. While wondering, there seemed to be three ways for the youth to find a solution for their way of life.

These youngsters lived mainly lives of leisure since there was nothing to do, living on their parents' expenses the war against capitalistic society, expressed by waving secretly a red flag on an electric pole on May 1st, by distributing handwritten “Proclamations” on October's Revolution Day and by preaching in “Political Meetings” to some tailors' apprentices. They read Plekhanov and Bukharin, Marx, Engels, and Lenin. At their parties they sang revolutionary songs and read from I. L. Peretz, who for some reason was considered a cosmopolitan and heretic, or they read “The 13 Pipes” by Ehrenburg. They tried to dismantle the regime's foundations, and what is interesting is that the authorities treated them with all seriousness and harassed them as one would do with real revolutionaries, as if they really posed a risk to the rulers.

[Page 48]

One must admit that there was a lot of charm in their way of thinking, in their actions and their youth's enthusiasm, which they invested in their beliefs. It is a shame that part of this wonderful youth was lost in the Nazi inferno and the part that was granted entrance to their “redemption” gates felt cheated, disappointed, and desperate, people who lost their faith twice.

Zionist Youth

Out of the buds of youth movements which begin with “Hibbat Zion,” that had not yet found their path in clear ideological patterns or paved roads to fulfillment, came together during the second half of the twenties; Zionist youth movements whose essence, education and thinking, were influenced by the reality in Israel and the political and settlements policies that were being established there.

The General Youth movements Histadrut and “Hatehiya” in those years was not able to respond to the ideological demands of the different movements that existed and led to two youth movements: “Gordonia” and “Freiheit.” Later, came “Betar” and the “Mizrahi” youth. The youth movement “Maccabi” became a shelter for the Zionist “Golden Youth” of those days.

The Zionist youth movements attracted a multitude of the town's youngsters:

The strengthening of the youth movements peaked during the thirties and became the core and content of life of all the town.

Many hundreds of young men and women were already organized in youth's unions, dozens of the older ones were now in training, and some of them had made Aliyah. No doubt that if fate would have added around ten more years of activity to the youth movements, we would have witnessed the town void of her youngsters, while most of them would have headed to Israel.

Kibbutz Nir-Am

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Edineţ, Moldova

Edineţ, Moldova

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 16 Jul 2022 by LA