|

The photograph was taken by Gavriel Rayner in 1955

|

|

[Col. 591]

| A voice is heard in Ramah Lamentation and bitter weeping Rahel weeping for her children She refuses to be comforted. |

| Jeremiah XXXI, 15. |

[Col. 595]

Yehezkel Berlzon

During the summer of 1939, the tensions between Poland and Germany increased. Accusations and counter-accusations were heard daily. The threat of a German attack on Poland became ever more serious. But the Jews of Suwalk, a city right near the German border, did not believe, somehow, that Hitler would start another world war. They considered, and thought, and feared - - but still doubted the possibility of a second world war.

The heat was dreadful. In Suwalk, the Jews joked that the war was on vacation. Not a few Suwalk Jews left for their vacations in the country, or even went abroad.

The communal workers were very busy in those fateful days, caring for the Jews of Zbonshin, whom Hitler had suddenly deported from their homes in the winter of 1939 because they did not possess German citizenship. For a long time they were in a “no-man's land”, because Poland did not want to let them in. In the spring of 1939, a few dozen of these Jewish families were brought to Suwalk and the communal workers were busy finding places for them to live, as well as food and clothing. The committee for the Zbonshin refugees formed in mid-winter sent large sums of money to the central committee in Warsaw. Now they were involved in giving direct assistance to the deportees from Germany. The last rabbi of Suwalk, Rabbi David Lifshits, headed the committee. Among the members were: Yaakov Kisnezshitski, president of the community; Lawyer David Mernshteyn (now in Chicago), director of the gymnasium; Engineer Binyamin Efron; Dr.Naftali Staropolski; Hone Sukhovolski; Hayim Raykhman; Shakhna Finkl and others.

The Zbonshin victims in Suwalk were a living warning that Hitler stopped at nothing and that they should prepare for the worst.

[Col. 596]

And yet, life went on fairly normally – and the communal work did not come to a standstill. During the summer months of 1939, work on the new poultry slaughterhouse was completed and some new ritual baths were built in the Jewish communal bathhouse in the Shulhoyf.

All of this was done even though the Jews of Suwalk, living as they did on the border with Germany, actually felt the dangers of war. For example, on the eve of Passover 1939, the following event took place:

Since Suwalk was a border town, it usually had four or five Polish regiments stationed there. Among them, there were some 500-600 Jewish soldiers. The Jewish community and the Rabbi saw to it that the Jewish soldiers get leave during the High Holidays, and they provided them with kosher food on Passover. Immediately after Purim, two committees of men and women would begin preparations for a grand Seder for the soldiers. The purveyors would provide the matzoth, the butchers the meat, the fishers the fish, etc. It was a long established custom that on the night of Passover, after evening prayers, the rabbi and the finest householders in town, would go to the large hall which had been specially prepared for the Jewish solders, and celebrate both Sedarim there with them. The garrison commander would give permission for this event. This permission was always easy to acquire, but the last Passover was very different. The commander absolutely refused to allow the Jewish soldiers away from the barracks for two days and allowed them only a few hours off to pray in the synagogue and to eat in the Jewish kitchen. His reason: “we must be prepared”, encouraged the pessimists in town. However, as days and weeks went by with no sign of trouble, Jewish optimism once more got the upper hand. People walked around in deep depression yet, not without a ray of hope, that somehow there would be some kind of peace settlement in the world.

The month of Elul came when everyone was in this mood between fear and trust. It was cloudy from time to time, and there was wind and rain.

[Col. 597]

People felt haunted and helpless in their hearts. Rosh Hashanah was approaching and the spiritual accounts that one must make, demanded more thoughtfulness and pain than in previous years.

It was in this fateful month of Elul that the great panic broke out. In the middle of the night, between Wednesday and Thursday, on the 9th of Elul, 24th August 1939, the police knocked on the doors of the houses where {escapees from the army?} lived as well as reservists and demanded that they go to the army quarters. In the morning there were posters hung all over the city that there was a general mobilization. This was immediately after the infamous treaty between the Soviet Union and Germany, via their Foreign Ministers, Molotov and Ribbentrop.

The world turned dark for Suwalk's Jews. The women ran around wringing their hands – some ran to the rabbi and asked him to pray that their husbands and children should return safely. Dreadful scenes from the First World War flashed before people's minds. The wealthiest merchants and householders began to leave the city. Every day, the city became emptier. Only those without strength or means remained – old, sick, poor and the plain middle class people. Some of the rich people also remained. They argued that it did not pay to run away. It could only lead to impoverishment, wandering around poor and homeless, dirty and hungry in strange cities. They had learned this lesson during the First World War. Suwalk was not a strategic place – there would be no battles there, and even if they fled, they might not avoid the war anyway.

But in moments like these, logic has no place – only fear and fear urged the masses of Jews to flee from Suwalk into some more central cities of Poland, closer to the Russian border. Since many of the communal leaders were among those who fled, the need of the poor population became greater. A special small committee headed by the rabbi was formed for the emergency period.

Things began happening very quickly. Friday morning 17th of Elul, September 1, 1939, the President of Poland, Ignacy Mashtsitski, received a declaration of war from Germany, and by 1p.m., Nazi warplanes had already bombed Suwalk.

[Col. 598]

The German army crossed the Polish border and were awaited in town momentarily.

On Saturday, the second day of the war, the town was heavily bombarded and there were many victims in the barracks and train station. German bombs fell almost every day, but no German soldiers could be seen. Hitler's army had already penetrated deep in Poland, but Suwalk and other border towns were still free. How could this be explained? None of us had an answer to this question.

Life demands its dues even in the worst moments. When the air raid sirens sounded that bombers were approaching, people ran to their cellars. But the weak, sick and poor had to be cared for. This was the task of the newly formed small committee. One of its worries was what to do with those Jews who were in jail for minor crimes? It was a mitzvah of saving a life to remove them from there, but it was also life-threatening to go there to ask for their freedom. The rabbi decided that the jailed Jews must be rescued, and he, together with Dr.Naftali Starapalsi, took upon themselves the task of going to the head of the jail about this matter. On their way, the sound of approaching bombers was heard. They dashed into a cellar, waited a while, ran into another hiding place, and made their way in this manner, from cellar to cellar, until they arrived. When they were on their way back from the jail, with the promise of the head of the jail to agree to their request – again, going from cellar to cellar – Dr. Staropolski said to the rabbi:

“Rabbi, we have to say goodbye. You, as the leader, must remain with the congregation. I must leave. Perhaps after the fires of war we will meet again in our Suwalk. Be well”, and they both began to weep.

Rosh Hashanah was approaching while people were in this bewildered, undecided and desperate condition. There was order in the town which was still held by the Polish military. There were no more out-of-town Jews in the garrison, but there were still quite a few local Jews. The rabbi went to the Polish commander of the city and asked him to allow the Jewish solders to come to pray. At first, the commander did not even want to hear him out, after all, it was wartime – but the rabbi answered that it was especially important during wartime for the Jewish

[Col. 599]

soldiers to pray to God during their holy days, for this would strengthen their might and courage in the fight against the enemy. The rabbi's argument worked.

It was seldom that the Days of Awe were as full of awe in the synagogue as they were that year. There was a mixture of fear of the Lord and of his mortal creatures, and the entire synagogue was full of fear and trembling. The fear strengthened the belief in our Father in heaven, whom we were asking for a healthy year. There were indescribable scenes of emotion, when the young men who had been mobilized had to say goodbye to their families after the prayers. The cries and weeping reached to the skies. “And their cries went up to the Lord”. The cliché: “May you inscribe for a good year”, had a new meaning. Every time someone shook hands and greeted his neighbour with this phrase, hot tears were spilt.

The question arose whether to open the large synagogues for the High Holidays. Before the holidays, some of the householders came to the rabbi and suggested that they remain closed for the German bombers might seek out these holy places in particular. It was a very difficult problem, but the rabbi and other communal leaders said that keeping the synagogues closed would increase the panic. It was suggested, however, that women and children attend services as little as possible.

On Shabbat Shuvah, which fell that year immediately after Rosh Hashanah, the situation became very critical and desperate. In the morning, the entire Polish garrison suddenly left the city. During the day, the police and mailmen left as well – and this was the clearest sign that the Poles had yielded Suwalk.

All kinds of rumours began coming in from all sides, that the Soviet army had crossed the Polish border, and had already entered Baranovitsh, Volkovisk, Lide, and was approaching Grodne, Augustow and Suwalk. Various accounts on the radio, told of the Soviet Union and Hitler Germany, dividing up Poland between them. Would Suwalk fall into the hands of the Soviet Union?

Meanwhile, Suwalk was without a governing body – a most suitable time for acts of hooliganism and robbery of Jews. There were rumours that along with the Soviet entrance into Polish territory, there were all kinds of ant-semite libels being spread by nefarious elements. There were excesses against

[Col. 600]

Jews in other areas as well. Thus it was urgent to form a Jewish guard in town.

A meeting was called in the rabbi's house for this purpose.

The few remaining youths and middle-aged people immediately responded to this important task. Some of the guards were armed. The leaders were: B.Genya, the printer: Gritshendler: Kalman Seglman: Avraham Ber Tsimerman – secretary of the artisans' society: Khatskl Zilbershteyn the baker: Moshe Kalinski, and others.

The watch was strengthened for Yom Kipur. According to the plan, some of the guards were to watch the section of town around Dolek, near the cemetery – others, the synagogues, and the rest – Jewish dwelling places.

Before Musaf, the rabbi sermonized before the frightened and broken-spirited congregants who packed the synagogue and he encouraged them. At the very moment that the rabbi was talking about the High Priest's prayer in the Temple on Yom Kipur about the men of Sharon: “that their homes become not their graves” and asked the congregation to pray that our homes become not our graves – planes passed overhead. The congregation became dumb as stone. All eyes turned to the windows to see the skies above. But this time no bombs fell.

Some of the leaders of the guards[1] came to the synagogue after Musaf. They gave the rabbi a secret message from the mayor that hooligans from elsewhere were on their way from Augustow to Suwalk to make a pogrom. The rabbi was as pale as chalk. What should he do? Should he tell the congregants? A panic might break out which could wreak havoc. Not to tell? Then he would have to take the responsibility for all these lives in case something did happen. But the rabbi did not lose control of himself. After much thought, he told the representatives of the guards to recruit a larger number of people to guard duty and to send them to the threatened area – the Augustow highway where the hooligans might be expected to come. Secondly, they should make contact with the local rowdies and hooligans, who were probably in touch with their “comrades” and promise them large sums of money and other valuables, if they would prevent the foreign pogromchiks

[Col. 601]

from entering Suwalk. The plan was a good one and it helped, as they learned shortly before Ne'ilah[2]. Nevertheless, they did not want to depend on the word of the local underworld. The rabbi ordered that the Ne'ilah be completed earlier {than usual} and that after prayers, everyone should go home, lock the doors tightly and pray to God that they be saved from all danger in the new year. The great pressure he had been under during the last few hours of Yom Kipur revealed itself in the rabbi's voice as he bade “Gut Yor”[3] to the two sextons, R'Hershl Bakhrakh and R'Mendl Staviskovski, after the large congregation had left for home.

The night was one of sleepless watching. No one closed an eye. Jewish guards were increased and strengthened. Young guards patrolled the Jewish neighbourhoods. They were ready for anything. They gave special attention to the orphanage, the home for the aged and the Jewish hospital. They also guarded the synagogues and the cemetery.

The night lasted as long as the Jewish exile, but it passed, and at dawn there suddenly appeared the first units of the Red Army.

In a few days the Jews who had fled from Suwalk began to return home – exhausted, hungry and broken-spirited. They had all suffered the same misfortune. No matter in which direction they had fled, they had been bombed by the Germans. The areas farther from the border and the large central cities of Poland suffered more from warfare than Suwalk itself. Many of these who fled had lost property because their goods had been stolen from their locked and shuttered homes. The plan of not fleeing proved better.

Shortly after the arrival of the Red Army, conditions became more stable. There were still plenty of torn-apart Jewish families, but the mood was somehow calmer. Rumours began flying about all kinds of territorial border changes between Germany and Soviet Russia. On the Sabbath, the first day of the intermediate days of Sukkot, the Soviet leaders called an open meeting in the city park, where they promised that Suwalk would remain under Soviet rule. A few days later, it was

[Col. 602]

seen that the Soviets were leaving the Suwalk area. The optimists comforted themselves with the idea that the Soviets would give Suwalk to Lithuania, as it had done with Vilne, but not many shared this optimism. The fear of falling into Nazi hands grew. As the days passed, the confusion grew greater. Hundreds of Jews began packing again and left in the direction of Augustow. Most of the Jews remained bewildered in their homes. It was Hoshana Raba. They waited for a good sign from the heavens and their heads were simply splitting from uncertainty – what should they do and how should they decide? Should they run from the town and seek refuge among strangers? But just a few weeks before, this had been shown to be senseless. Those who had fled regretted it later and envied their neighbours who had remained at home.

And how could they all flee? Here in town there were thousands of Jews – many among them old and sick – who could simply not leave their homes (the later horrors of the Nazis were as yet unknown, so many Jews thought that whatever happened to everyone, would happen to each individual[4]).

Hoshana Raba and Shemini Atseret passed with these heart-pounding fears affecting everyone. People gathered in the synagogues more than usual and prayed for salvation from misfortune. During yizkor on Shemini Atseret, there was a sudden tumult in the big synagogue that the Germans were already in town; a panic broke out. There was wailing and weeping, but in a while it was found that the report was groundless. It seemed that a few uniformed German officers had driven up to the staff headquarters of the Soviet, but who could know what they wanted? By the time the prayer for rain was said, the congregants became somewhat calmer and with a mixture of fear and hope, they cried out together with the cantor: For life and not for death.

By the time they were parading with the Torah scrolls, their mood had gotten even better. They heard from secret radio reports that the Suwalk region would be annexed to Lithuania. Joy became so great that Simhat Torah eve was celebrated as in the old days. Full of hope, they waited for better times.

But the hope did not last long. On the morning of Simhat Torah, in the middle of the parade with the Torah scrolls, people came to the Bet Hamidrash Hagadol to inform the congregants that the first German soldiers had actually arrived in town

[Col. 603]

and were taking over rule from the departing Russians. Darkness fell – Jewish hopes were quenched – they finished the prayers and

[Col. 604]

with trembling hearts, they all ran home and locked themselves in.

A few hours later, thousands of German soldiers with tanks and motorized artillery poured in from the direction of Ratzk.

[Col. 603]

Under Hitler's Rule

On the first day the Nazis did not show their true colours. The Jews sat behind locked doors, looked out through their blinds. A few Jews, who were brave and went out on the streets, told that the German soldiers did not touch anyone.

On the following morning, we began to hear different reports. Some Jews were beaten up by German soldiers; here and there Jewish shops were robbed. S.S. men were searching through the Holy Ark in the Bet Hidrash, and so on.

On the third day, on Sunday evening when the rabbi was going to the synagogue for evening prayers, a Polish messenger came to him and informed him that he must go immediately to the Gestapo. The rabbi took along the secretary of the community, Hone Zilbershteyn and the director of the Talmud Torah, R'Yitshak Levein and Leybe Rozntal.

Hatred and poison flashed from the eyes of the Gestapo who received the Jewish representatives. Their “good evening” remained unanswered. They were not asked to sit down. They were immediately given this ultimatum: “By eight o'clock in the morning, they must bring to the Gestapo a list of all the Jews in Suwalk and their addresses”.

The Jewish community leaders began to explain:

“It is not possible to make such a list in one night. Many Jews have fled from the city – and who knew who had remained?”

After long negotiations, the Gestapo agreed to give them until the next evening on condition that the first thing in the morning, they should bring a quantity of leather, coffee and chocolate.

A few days later, the Gestapo began catching Jews for forced labour. They would seize them on the streets – pull them out of their houses and send them away to dig trenches. They took with malice aforethought, old and weak people; the rabbi from the Shoemaker's kloyz – Rabbi Sheynhoyz – eighty years old;

[Col. 604]

The weak, old Leybe Krutsinitski and other old men. When young Jews volunteered to replace the old men, they were driven back with blows.

When the seizures of Jews became unbearable, a secret meeting of the community council decided to require every able-bodied man to volunteer for German work in order to prevent the capture of the old and weak. If someone did not wish to volunteer, he would have to pay a fine of 10 zlotys a day to the community so that able-bodied poor Jews could be sent in their place and paid for their work. In this way, too, they hoped to solve the problem of supporting people who had no means. This also helped get the agreement of the Gestapo that the Jews themselves should provide the quota of workers. The motive was that the Jews would pick out young and able-bodied men for the work and thus avoid panic in the city. This brought some calm into the city.

A strict order went out that all shops must remain open and there would be the death penalty for anyone hiding goods.

Community life was once more re-organized. They had to care for the orphanage, the home for the aged, the Jewish hospital. Many refugees from the surrounding towns were in Suwalk at the time; from Baklerowe, Saini, Ratzk, Filipowe, Yelinewe, who had to be helped. Notwithstanding the abnormal situation, the rabbi and some of the communal workers opened the Talmud Torah for the new semester, under the supervision of the Director Levin, new teachers were hired to replace those that had fled, and were guaranteed their salaries. The girls' school was also re-organized. These activities sweetened the bitterness and despair which had overwhelmed the Jews in town.

This semi-quiet lasted for only a short time. In a few days, the seizure of Jews began again, and it was

[Col. 605]

impossible to go out on the street.

At this time, Kosher slaughtering was forbidden. The next day, the Gestapo ran to the rabbi. On the table in the Bet-Din[5], there was a knife. Thinking that this was a slaughtering knife, the murderers pulled the rabbi into another room, put the knife against his throat and ordered him to give them all of the slaughtering knives, if not, they said laughing sarcastically, “we shall slaughter the rabbi kosher”. When they let him go, they asked for a list of all the rich people among the Jews who had radios. The rabbi answered categorically that there were no rich men left in town and that he did not know who had a radio. Their threats did not help them and they left the rabbi without information.

A day before the same scene had been played at the community council. Hone Zilbershteyn, the secretary, had refused the Nazi demand and was given such a slap that he fell bleeding to the ground.

It became very bitter when the Gestapo called the rabbi and ordered him to close down the big synagogue, all of the houses of study, the smaller synagogues and schools. This broke him down after he had carried the weight on his shoulders of all of the dreadful events of recent past. When he came home, he told the assembled communal leaders: “if they take away our holy places, it is, God forbid, not a good sign”.

While the rabbi was giving the last mentioned report, the sextons, R'Mendl Staviskovski and R'Hershl Bakhrakh came

[Col. 606]

and told him that the Germans had come and had taken the keys of the synagogue and the Bet HaMidrash. Afterwards, the sextons of the other synagogues came and told the same story. The rabbi and the leaders of the congregation had considered, with the coming of the German armies, that the synagogues might be confiscated. Therefore, they had removed most of the Torah scrolls and had hidden them. They had left only a few Torah scrolls behind for ritual purposes and these could not be rescued any longer. The next morning, German trucks drove up to all of the Jewish businesses, took away all of the goods and brought them to the big synagogue, which then became a

[Col. 605]

concentration point. All of the work was done by captured Jews.

|

|

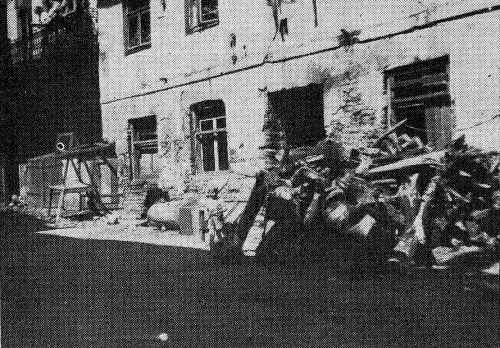

| Zilberblat's kloyz on Turme Street completely destroyed The photograph was taken by Gavriel Rayner in 1955 |

[Col. 606]

|

|

| The big synagogue within the holy ark, torn from its place One can barely see the words “Keter Torah” above. The floor is torn up |

It was dark for the Jews of Suwalk. Their holy places were desecrated, their property pillaged – what would tomorrow bring?

The violence, robbery and beatings became worse from day-to-day. There were also libels against Jews. For example, a Christian wigmaker, who hated his former boss, threw a gun into his courtyard and informed the Gestapo who immediately arrested the Jew. The Jew was saved from hanging by a last minute miracle. When the pit had been dug and he was ordered to undress, he was saved by a young man from Psherosle, Avraham Matulski, who had an entrée to one of the leaders of the Gestapo because his father had done business with him before the war.

[Col. 608]

On many occasions, this young man saved a number of Jews from troubles. Finally, he was himself shot to death.

But the few successful interventions for Jews at the Gestapo could not lessen the great sea of troubles and misfortunes which poured over the Jewish population.

The desperate and bewildered Jews did not even have a place to weep for the synagogues had all been closed down by the German power. Prayers in private homes were also prohibited.

There were problems caring for the sick. The two Jewish drugstores of Leon Abran and Yehoshua Shvartsman were closed. There was not one Jewish doctor in all of Suwalk. Dr. Leon Smolinski, who had been mobilized into the Polish army from the start of the war, came back to Suwalk on a few days before the deportation.

[Col. 607]

The deportation

But all of this was only a prologue to the destruction of the Jews of Suwalk.

On the Sabbath of the Portion Lekh-Lekha, the eight of Heshvan, {5}700, (21 October, 1939), when a secret quorum of Jews had completed their prayers in the Rabbi's house, a former Polish officer came in. The rabbi knew him. He gave them a demand from the Germans that on Monday morning, the rabbi and two representatives of the community must come to the German headquarters to hear an order concerning the Jewish population. In the evening, the same news came from a Jewish tailor on Koskiusko Street, who had been told this as a secret by a German official. This time, the information was very clear. An order was being prepared to expel all Jews from Suwalk.

The impact this news made is indescribable. Sunday, the rabbi called a meeting to consider the possibility of trying to prevent or ameliorate this expulsion order. It was also decided that Shakhna Finkl and Hone Zilbershteyn would go along with the rabbi to the Germans.

The German civilian who received the Jewish representatives on Monday morning, immediately roared out at them without looking them in the face: “All Jews must leave Suwalk within

[Col. 608]

three days”.

The Jewish delegates began to plead, to beg and to cry: How could this be done and where could they go since Suwalk was on the border?

The German answered: “You can go to Mars but you must disappear”. He then added: “If not, it will be worse for you”.

The only thing they were not able to achieve was an agreement that the next day, Tuesday morning, a representative of the Jews would bring to the headquarters a request with a plan on how to ease, in the slightest way, this terrible decree.

Broken and despairing, the Jewish delegates left the headquarters. Many Jews were waiting for them despite the order prohibiting the assembling in groups. Wesola street, where the rabbi lived, was black with Jews. They surrounded the rabbi who told them with a cracked voice: “Jews, we need mercy. A decree of expulsion hangs over our heads. Maybe we will succeed in staving the decree, but meanwhile, everyone must prepare to leave. We leave behind, my brothers, the houses

[Col. 609]

of study and the cemetery. Let us pray to God that we may soon return”.

Wails accompanied these words from the leader of the congregation. Women and old men ran over to the rabbi and cried: “Rabbi, what will happen to us”?

|

|

| The old entrance to the Suwalki Jewish cemetery |

At the community council, a meeting was called to consider the situation. After six hours of conferring, they worked out a 16-point plan. The most important of them was that they should ask the German command for permission to send two Jewish committees to the borders of Lithuania and Russia. Perhaps they would persuade them to allow the expelled Jews to come. They also decided that the wealthy Jews must give the congregation treasury worth 10% in cash for distribution to the poor who would try to get over the border using this money {as bribes?}. Another point of the plan was to mobilize all wagoners with their horses and wagons and all Jews who had acquaintances in nearby villages, would immediately go there and see to it that on the third day (the day of the expulsion) peasants would come with wagons to take them. They also had to ask the Germans for permission for a gradual expulsion, whereby a minimum of 100 Jews would leave every week.

Early the following morning, Dr. Leon Smolinski and Hone Zilbershteyn left to give the plan to the Germans. Six thousand people awaited their return with pounding hearts. The result of their visit was:

[Col. 610]

This brought some calm. Again, little bits of hope began to appear. Perhaps they would somehow be saved from Hitler's paws. They breathed a bit easier. It is, after all, war-time. Who knows – something could happen in two weeks.

On Friday 14 Heshvan, one committee left for the Lithuanian border near Kalvarie. A Jewish chauffeur named Tsviling, still had an old automobile. He was required to drive the committee which consisted of Rabbi David Lifshits, Suvalski (who spoke Lithuanian), Leybe Ariovitsh, and another person.

A whole congregation of Jews escorted the delegation with its profoundest prayers that they should succeed in their mission. The representatives themselves knew that the fate of a community of Jews was now in their hands. Should they succeed, there would be peace and rescue, and if not, it could mean death and destruction. Every one of them prayed the old and tear soaked prayer: “Make our path successful”.

Any journey at that time, especially for Jews, was very hazardous. The automobile was stopped by German police a number of times. But the written permission from the German commander in Suwalk always worked. At the last point, the

[Col. 611]

German did not examine the papers and even escorted the committee a short way towards the Lithuanian border patrol. However, the Lithuanian police did not allow them to approach. With tears in his eyes, Suvalski, the Lithuanian speaker, told the whole story and said that the committee was only going as far as Kovne to talk to the local Jewish leaders. The Lithuanian officer did not allow this and did not even allow the delegates to go to the nearest Jewish village for a few hours. When they asked for permission to telephone to the rabbi in Kalverie, not far from the border, or he could telephone himself, he asked his superiors and was told: “No this is wartime”.

The delegation was on “no-man's land”, between the German and Lithuanian border police. When the Lithuanian officer started walking away, the rabbi and the members of the committee started to follow him to beg for mercy. He warned them harshly: “three more steps and I shoot”.

Exhausted, worried and depressed, the delegates returned to Suwalk.

The committee to the Soviet border was also unsuccessful. The members of this committee were: Dr. Leon Smolinksi, Shakhna Finkl and Avraham Ber Tsimerman – the last named were artisans and workingmen. It was thought that perhaps in this case that would be helpful.

On the Soviet side, they were permitted to cross the border and they were received by some military leaders. They reported the tragic condition of the Jewish population of Suwalk and appealed that the border should be opened for a few hours. The answer was that they had no right to open the border without permission from Moscow. The last request that divided families be reunited was also denied. (Hundreds of families were split apart when some remained in Suwalk and some fled to Augustow).

Only one thing was allowed. They put together a petition to the Soviet government in Moscow to open the border. The delegation received a promise that they would be told the answer.

The reports of both committees put the Jews into the deepest depression. All the borders were closed to them. There was no rescue, and the days ran by. One week went by and from hour-to-hour, the question became more tragic and frightening: “whence cometh my salvation?” The only thing they could do was send secret messages via gentiles to the rabbis of the nearby Lithuanian villages and warn them of the great danger.

On the Sabbath, 15th of Hesvan (28 October), a gentile brought a note to the rabbi from one of the finest Jews in Saini, R'Moshe-Leyb Lev, an eighty year old man. He wrote that all 573 Jews of Saini had been expelled on Thursday. For three days, they have been wandering in the fields, five kilometres from the Lithuanian border. They were suffering from cold and hunger. One woman had died and there were many sick people. They were begging the Jews of Suwalk to help them. The note ended with the words {in Hebrew}: “Put your house (affairs) in order and bury your dead”.

Two wagon loads of food and clothing were immediately sent via some gentiles. The next day, Sunday, the rabbi and his committee left for Saini in Tsviling's car. Their aim was to get in touch with the Jews of Saini and to try to reach the Lithuanian border from that direction.

They saw a sorrowful scene before them as they drove through Saini on Sunday morning. The market was full of peasants who were enjoying themselves quite cheerfully, but the Jewish homes and stores were empty and broken into. There was no sign of Jewish life which had throbbed here for hundreds of years. At the bridge on the outskirts of town, the Jewish delegates were arrested by the German police. “Jews, what are Jews doing here?” they screamed with murderous hatred, but the letter from the Suwalk commander helped here too, and they were allowed to proceed.

By various means, they were able to reach the Jews from Saini who were in the fields. It was a frosty day, bitterly cold, and here and there on the fields and on the sides of the highway, Jews ran to and fro in order to warm their bodies. When the car stopped and the Suwalk delegation got out, there was such a rush on the car that during the first few moments they could not even talk to each other. The poor abandoned ones thought that the Suwalk Jews had come to rescue them and they began to rejoice; the day before, they had received bread from Suwalk and now the rabbi and the householders had come to take them out of there ---

[Col. 613]

How could it be otherwise? When they heard the problems of the Suwalk delegation, they were even more broken and with weeping voices, they told the story of the expulsion from Saini.

Thursday evening, on 26th October, all of the Jews of Saini were driven out of their homes by the Nazis to the Lithuanian border. Since the Lithuanian border patrol did not let them through, all 573 of them stayed in the field all night. Their cries and screams reached to the skies. On Friday morning, the gentiles on the Lithuanian side of the border came to see what was going on. The story reached Kovne and journalists from American newspapers came to see what was happening and took pictures of the unfortunate Jews. It seems that the Germans noticed this and did not want the world to learn of their actions, so they drove the Jews back some kilometres from the border and enclosed them in a wedge between the border and the town. The surrounding villages were warned not to take any Jews into their homes, and if they did not obey, all of their property would be burned up. In this way the Jews wandered around for three days without shelter, suffering from cold and hunger; they looked awful, depressed, broken and bewildered.

In the wind and the cold, the Suwalk delegation met with the Jews of Saini, out on the field and could find no solution to their problems. What should they do? Should they return to Suwalk or should they try to cross the border into Lithuania at night?

They saw a frightful scene when the Saini Jews showed them a young boy, terribly sick, lying in a stall at the edge of a peasant's farm. The rabbi ordered a wagon to bring him to Suwalk and the community council would pay.

From there, the delegation drove to a border point where there was only a watchman. But here too, they could do nothing, and with broken hearts, they returned from the border yet a third time.

They still did not give up hope of breaking through at some point in the Lithuanian border – this time, through the town of Wizshan. Again, Rabbi Lifshits and the above-mentioned communal workers, went in the same car, taking along bread

[Col. 614]

and enough food for the starving Jews.

By then, the Jews of Wizshan were also out on the fields. When they saw the car they thought it was full of Germans and they began to run away. But, when they saw that Jews were getting out of the car, their joy was unrestrained. They told how the Jews had been driven out of Wizshan Friday morning, 14th of Heshvan {27th October} and how they had been wandering around for five days. Some of the Jews had managed to sneak across the border and were in Vilkovishk.

This time too, the Suwalk delegation had no luck. On the way back, they were arrested by Germans who brought them to Wizshan. While they were being held by the police, their automobile was wrecked. They were finally able to get permission to have the automobile repaired so that they could drive back to Suwalk.

The fifth and last attempt to cross the border of Lithuania in order to report to the leaders of the community there on the terrible condition of the Suwalk Jews, was on Monday 24th Heshvan {6th November}. There were rumours that the Jews of Punsk had succeeded in sneaking over the border into Lithuania during the night. On this occasion, the Suwalk delegation moved in the direction of that town. They did not find any Jews in Punsk. In a nearby village, they met a Jewish boy who used to lead Jews across the border. He brought the Suwalk delegation to the right place but they could not negotiate with the Lithuanian border patrol.

An entire Jewish community was at a dead-end. Everyone knew that the only escape was across the border but there was no way to get across. Everyone asked the same question: “What's to be done?” and there is no answer.

And now the end of the two-week extension was nearing. A gentile came to the rabbi and gave him a note from Rabbi Bengis in Kalverie. He wrote that the Jews of Lithuania already knew the tragic story of the Jews of Suwalk. They could not do anything officially, but perhaps they would be able to get the protection of the Lithuanian government for those Jews who had already crossed over the border. Rabbi Bengis suggested therefore,

[Col. 615]

that they should try to cross over by any means and in any way possible.

|

|

| Rabbi Shimon Ze'ev Bengis of Kalverie and Leyb Lipshits when the books came from Suwalk {on photo in script in Hebrew} the books arrive. Suwalk {from Suwalk?} |

Rabbi Lifshits immediately reported to the communal council which immediately notified all the Jews in town. The confusion was unimaginable: where should they flee – Lithuania or Russia? How should they flee – single or in groups? What should they do with their families, with relatives? What about the sick or weak? Should they be taken along or left behind?

But the knife was at their throats – so they began to flee – some towards Russia – some towards Lithuania. A few got through – some came back and others were killed. Moshe Giltshinski and Mrs. Mariampolski-Broyde were drowned in the Augustow canal near the Russian border.

In Suwalk itself the seizure of Jews for forced labour and the beatings of Jews escalated. Khatski Fridman was shot on the spot because he defended his father, R'Hirshe, an eighty year old man who was being dragged away for hard labour.

Wednesday morning, the 26th of Heshvan {November 8th}, many Jews, among them Rabbi Lifshits, received notes from their relatives across the Lithuanian border. The letter to the Suwalk rabbi was written by his relatives, the rabbis of Vishay, Zosle and Vevie, Rabbi Yehezkel Goldshlak, Rabbi Moshe Levin and Rabbi Nehemia Fayn, may God avenge their blood. (Later, in {5}701-1941, they were all killed by the Nazis in Lithuania). They advised Rabbi Lifshits that he and his family should immediately get on the wagon of the peasant who had brought the letter and return with him. The rabbi did not want to leave his congregation in such a dreadful time, and he sent back only his wife and his two small children, one of them five months old, together with a large group of Jews,

[Col. 616]

and also the old Rebbetsin, Yoselevitsh, his wife's mother. As they were crossing the border, the baby began to cry and the Lithuanian border patrol tracked them down and began to shoot and the tiny child was killed in the dark. In the great tumult, the five year old who had been led by a peasant from the village, also went astray. In the confusion many of the Jews ran in all directions. In the dark some of them succeeded in running through the forest on the border and reached the other side. Some were caught by the Lithuanian border patrol which sent them back to the German border. Among those who were arrested was Rebbetsin Lifshits with her dead child. She begged in vain for mercy to allow her to cross the border. Nothing helped. She and her dead child were returned to the German side. The rebbetsin stayed in the village {on the border} for a few days thinking that she might somehow be able to cross over. She did not want to return to Suwalk because she did not want the rabbi to learn of the tragedy. But the border became even more heavily patrolled and sick and broken-hearted, she returned to Suwalk.

On Sunday, the first day of Kislev, the baby was buried in the Suwalk cemetery. In the evening, the old Rebbetsin, barely alive, was brought back. She and some other women had been arrested by the Lithuanian border patrol and sent back to the German side. The women underwent a terrible ordeal during those few days; they were locked in a stall in the open field, cold and hungry and everything was taken from them, even their marriage rings. They were brutally beaten. They barely managed to make it back to Suwalk.

The tragedy of the rabbi's family shook the whole town. Everyone began urging the rabbi to find a way to cross the border so that he could track down his little girl. It was very difficult for the devoted leader to part from his beloved community, now in ruins. He and his wife and another two Jews left Sunday night leaving behind his rabbinic home to travel over the fields. He was escorted by his closest friends who had hired a wagon to take him to the border, and they all wept, broken-hearted and desolate.

[Col. 617]

In the pitch black night, the rabbi's wagon and the other wagon accompanying them, met a wagon coming from the opposite direction. In the dark they heard a voice call out in Polish: “who goes there? Can it be the rabbi of Suwalk?” A shudder went through the rabbi's body. Who knew what this strange question could mean? Perhaps there was some news of his little girl – lost in the field. In doubt, he replied: “Yes”. Once more the voice called out in Polish: “Don't go on the highway, it is full of patrols. Use the side roads”. No one knows to this day who this Polish guide was. Because of his advice, the rabbi was able to avoid great danger. But it did not end there. At midnight, they reached the border. There they had to climb over hills and valleys for several hours to avoid the border patrols. At the slightest sound, they had to fall flat on the ground. On a number of occasions, they saw the light of flashlights – of watchmen on the border, and then they held their breaths and crawled backwards on all fours.

Before daybreak, they were in a thickly wooded area. They were already a few miles into Lithuanian territory and they thought that the danger had passed. The guides decided to hire a wagon in the nearest village to take them to Kalverie. Worn out and exhausted, they sat in a big wagon belonging to a Lithuanian peasant which was pulled by two strong horses. At first everything went smoothly then suddenly they heard a cry in Lithuanian: “Stok!” (Halt). This was a command from a police unit. Knowing full well that his horses and wagon could be taken from him as punishment for transporting Jews, the peasant whipped his horses to run faster. Once again the cry of “Stok!” was heard and then the police started shooting at the wagon. The travellers lay down on the floor of the wagon and the rabbi started saying the viduy prayer[6]. By a miracle, they came upon a little side-road in the forest and the peasant quickly turned in to it and they were saved.

The peasant did not want to keep the illegal “merchandise” on his wagon any longer and he put the Suwalk Jews off his wagon. He showed them a little house on a hill in the distance,

[Col. 618]

where they could rest. Willy-nilly, they made their way to that place. How they rejoiced to meet an old Jewish woman in the house who came from a dairy-farm in the village not far from Kalverie. She received them warmly. She told them that it was not safe for them to stay too long because the farm was often visited by “Shiulists”[7] who were arresting all newly arrived Jews.

What could they do? Where could they hide meanwhile? How could they get to the town as quickly as possible? The major concern was the rabbi because he was much more distinguished looking and was obviously not a local person. Fortunately, a young Jewish man came by to get his milks cans. There was a short consultation and it was decided that he would take the rabbi to Kalverie in his wagon. It was also decided that he would send a wagon from town to get the rest of the Jews.

Approaching the town, they saw young Jewish people who would wait for refugees from Suwalk every morning and find houses form them to hide in. They were very excited when the milkman told them whom he had in his milk wagon.

“Shalom aleykhem, rabbi” they called joyfully. “Your little girl is here in Kalverie. We'll tell you the details later. Meanwhile we have to find a Jewish house to hide you because the “Shiulists” lie around here in wait”.

The rabbi asked them to send a wagon immediately to get the rest of the refugees into town and they promised to do so.

The rebbetsin, very concerned about her daughter, did not want to stay on the milk farm. As soon as the rabbi left, she started walking to town. Not far from the bridge, she was seen by “Shiulists” who arrested her. However, since this was within the borders of the town, she was taken to the Kalverie police station. She told Jewish passers-by who she was and they consoled her and told her that the child was in town and they would worry about her safety.

After much negotiation in the “high windows”[8] she was freed. The rabbi's little girl was brought to her parents and the town was happy with the result.

[Col. 619]

On the morrow, the rabbi of Kovne telephoned to the rabbi of Kalverie and asked about the rabbi from Suwalk for he had heard that the Germans were searching for him up and down the border to take him hostage. This was later confirmed by a letter from the old rebbetsin in Suwalk who wrote that on the day after the rabbi left town, Germans came to take him as a third hostage (along with the previous captives, apothecaries Svartsman and Erdraykh).

With the arrival of the Suwalk rabbi in Kalvarie, the attempts to bring Jews over from the German side increased. Every night more Jews sneaked across the Lithuanian border. A large number of them came to Kalverie and the rest to Vilkovishk and Lazdey. One cannot describe the acts of hospitality performed by the Jews of Kalverie and of the other towns towards their unfortunate brothers. There was not a Jewish home without a room full of Jews from Suwalk. They provided bedclothes, clothing and food.

The community of Kalverie set up a special committee to take care of all matters relating to the refugees. Its active members were: Aba Yakobson (from the electric station); the vice-mayor of town, Aba Blumenzon; lawyer Malakh; Kronzon; Kaganski; Yansburski; Vigderovitsh; and others. This committee concerned itself not only with the Jews already in town, but also did its best to rescue as many Jews as possible from the other side of the border. They had spread the word in the border villages that those who brought Jews into Lithuania would be well paid. For about three or four weeks, young people from Kalverie made trips into border villages to see if there were ways to help Jews cross the border.

About 3000 Jews altogether were able to cross from Suwalk area into Lithuania. The central committee to aid the Suwalk refugees was in Kovne, under the leadership of Rabbi Avraham Duber Shapira – rabbi of Kovne, may the memory of the righteous be a blessing. Rabbi Shemuel Aba Senieg, who was then the Lithuanian army chaplain, did much to help. Also active were the committee members: Reuven Rubinshtein, editor of the Kovne “Idishe Shtime”; Rozovski, director of HIAS; David Itskovitsh; Y.Yedidiah; Dr. Binyamin Berger; R.Khasman and the “Joint-Appeal” for Lithuania.

[Col. 620]

The rabbis and communal workers of all the cities raised large sums of money to help the Jews of Suwalk.

At a later date, the Suwalk relief committee in New York also sent money and clothing for the refugees.

|

|

| Some of the rescued from the Fisherman's kloyz. One man holds a Scroll of the Law |

Escaping to Lithuania did not always go smoothly. There were many tragedies. Some people were sent back, others killed.

Blumberg from the glassware shop was captured near Kalverie. On his way back, he sank in the Torf Swamps. His wife and son crossed over safely.

During his escape, frostbite attacked the feet of Dr. Shtern, a well-known dentist from Suwalk. He was brought to the Kovne hospital in bad shape and died there after much suffering. He was the father of the famous Avraham Shtern who later founded the Lehi group[9] in Erets Yisrael.

Kramarskin, the mason, former sexton of the Hevra Kadisha[10] was left lying at the side of a path by his daughter and son-in-law, for he had suddenly died and they continued on their way across the border to Kalverie. When the rabbi and other refugees heard this, they were appalled.

There lies a corpse on the field, abandoned. He must be buried in a Jewish cemetery. It was difficult to get peasants to cross to the German side to look for the corpse. Specially hired emissaries found him and brought him to Kalverie.

The funeral was set for Sunday, 21 Kislev. A large crowd gathered in the synagogue courtyard and Rabbi Gershon Broyde, son-in-law of Rabbi Binyamin Magentsa, and the last Dayan of Suwalk, eulogized the dead man.

[Col. 621]

With words, he quoted the passage from the Bible: “For indeed I was stolen away from out of the land of the Hebrews; and here also have I done nothing that they should put me into the dungeon”.[11]. He spoke of the tragedy of Suwalk and of all of the victims who fell by the wayside and depicted the dead man saying to those attending: “I am a stranger and a sojourner with you; give me a possession of a burying-place with you….”[12] as he said these words, the Dayan fell to the ground. He was brought into the synagogue and everything was done to arouse him but the doctor said that he had died on the spot.

The tragedy was indescribable: Here was a coffin containing a corpse brought in from the field, and here was another such misfortune. There was great weeping and mourning as well as confusion in the town of Kalverie.

The following day, 21st Kislev, was the funeral of the old Dayan of Suwalk with the participation of the entire community of Kalverie. The Suwalk Rabbi and Rabbi Gershon Gutman, Rabbi of Kovne read heart-rending eulogies. When the weeping Rabbi Lifshits described the frightful condition of the Jews left in Suwalk, he called upon everyone to pray for them – such wailing and weeping broke out in the synagogue that the very walls shivered.

Not all the Jews of Suwalk succeeded in fleeing. About 3000 souls remained there. There were a few quiet weeks. The Germans saw that the Jews were departing on their own so they waited and did not order deportations. The Jewish baker, Fayvl Oyern, was permitted to bake bread. Jews took this as a good sign and rumour went around that since so few Jews remained in town, perhaps the Germans would leave them alone and they would be able to remain where they were.

Poverty increased from day-to-day and there was simply no money. A Suwalk tailor risked his life to bring a letter across the border to the Suwalk rabbi in Kalverie. The letter was written by an important member of the Community council, Hone Sukhavalski, who described the situation and asked for urgent help. The rabbi did not rest until he had raised a large sum of money which he sent back with the same tailor.

The quiet days did not last long. On the Sabbath, 20 Kislev, {5}700 (December 2nd 1939), an order was suddenly promulgated that no Jew would be allowed to leave his house for a period of

[Col. 622]

three days.

On Monday morning the city was invaded by German police and S.S. The streets were blocked off and all the Jews were herded into the big synagogue, the Jewish hospital and in the jailhouse. They were all searched and their valuables taken away. Heartrending scenes were played out at all of the gathering places. All of the Jews were then taken to the train station where they were put into railroad cars which were surrounded by fierce dogs. After two days and nights of traveling, through East Prussia and the Warsaw area, they were unloaded in Lukov, Biale-Podlask, Partshev and other towns in the so-called Lublin Reservation.

On that same fateful morning when the deportation was going on in Suwalk, many families managed somehow to escape via all kinds of side streets and backyards, to neighbouring villages. Since it was now clear that there was nothing to lose, they decided to risk an attempt to cross the border rather than to fall into German hands. Some of them reached Kalverie the next morning. Among them was R'Yisrael Zavoznitski (now in New York) and R'Moshe Raflzon (Raphaelsen?), two important householders, who immediately reported to the Suwalk Rabbi the tragic news from Suwalk.

From their descriptions, it seemed that there were hundreds of Jews hiding in villages waiting for an opportunity to cross the border in Lithuania. Large sums of money were raised immediately to help bring them over. The rabbi called a meeting of all the Jews from Suwalk. They ordained a fast day and everyone donated a day's worth of food in order to start a fund for rescuing their compatriots. The rabbi alerted the central refugee committee in Kovne and in the neighbouring towns of Mariampol, Lazdey and Vilkovishk. He demanded that 10,000 Lit (about $1700) be set aside immediately for the special rescue fund.

The whole of Kalverie refugee committee worked day and night with great devotion. They sent emissaries to the Lithuanian border and to the nearby villages to announce that whoever would hide Jews and bring them to Lithuania would be rewarded. Thanks to their efforts, a few hundred Jews were brought across the border after spending some time in the woods near the border.

[Col. 623]

Among them was the old rebbetsin, Mrs. Sarah-Rivkah Yoselevitsh (she was later killed in the massacre of the town Simelishok, the first day of Sukkot, {5}701 (1940), may God avenge her blood).

Not all the Jews who fled from Suwalk during the liquidation were able to achieve their goal. A few score were captured by the Germans and brought back to Suwalk. A note was received in Kalverie that 60 Jews were imprisoned in the Fishermen's kloyz {“in Yaakov”} together with Gypsies – who were beating and torturing them and even making spectacles of placing boards with nails sticking into the backs of Jews and dancing on them. Among the sixty, was Khatszkl Zilbershteyn? Moshe Kalinski, Nehemia Finkovitsh and their families. The Suwalk refugees in Kalverie came to an agreement with a young Jew from Yezne who had contacts in Suwalk and could take on risky assignments. He disguised himself as a gentile and taking along some peasants, he set out to rescue these Jews.

It was understood that they could not all be taken out at once. The young man from Yezne was told to take out the children, their mothers and old people first.

It was very doubtful if the “rescue operation” would work. But there was nothing to lose by trying. The Jews of Suwalk were

[Col. 624]

in the greatest danger and they had to try everything and anything to save them. How great was the surprise then when a few days later, the young children, women and older men showed up in Kalverie. The children were immediately placed with families known to them. It was a day of great joy in Kalverie. It was a drop of consolation in the sea of sorrow and tribulation.

Encouraged by his first success, the young man from Yezne returned to Suwalk with a few wagons. He succeeded in rescuing all sixty Jews and bringing them safely to Kalverie. Zilbershteyn, Kalinski, Finkovitsh and other younger men, were so dreadfully beaten that they had to lie in bed for a long time.

Jewish holy objects remained in Suwalk. A few hundred Torah Scrolls hidden in the cellars of synagogues and private homes. The rumour spread in Kalverie that parchment from the Scrolls was being sold to cobblers. Some peasants brought whole and ripped-u sheets of parchment to the Kalverie market. People were aroused to save the holy books. The rabbi had been worried about this even before it was difficult to find a way to bring them out. Most of the Torah Scrolls were walled-in, so how could they get to them? But now that the gentiles had found so many hiding places and were desecrating the Scrolls,

[Col. 625]

There was no solution but to send gentile emissaries from Kalverie with instructions on how to find the hiding places. They were also instructed to go to the cobblers and buy up all the fragments of parchment. The Suwalk rabbi persuaded one of the best and most devoted of Kalverie communal workers, Hirsch Kaganski, to lay out $900 for this purpose. Kaganski's house was one of the finest in town; there the refugees from Suwalk would be brought from the woods. Kaganski and his family gave up their beds and their whole house for weeks at a time for the refugees; and may his name be blessed. The remaining Scrolls of Torah were brought to his house from Suwalk. Many were torn and about 60 scrolls were rescued. A separate ark was set up in the Kalverie Bet-Hamidrash for the Suwalk scrolls, and they were carried with great pomp from Kaganski's house to the Bet HaMidrash. The people followed the canopy with a mixture of joy and sorrow in their hearts – everyone wept and everyone thought: These holy Scrolls of Torah have shared the fate of Suwalk's Jews – some rescued but many torn and shamed.

[Cols. 623-624]

|

|

| One side of the big Suwalk synagogue after the Holocaust – entrance to the synagogue courtyard |

[Cols. 625-626]

|

|

| The rabbi of Suwalk, Rabbi David Lifshits, with the rescued Scrolls. On the right is Mr. Hirsch Kaganski of Kalverie |

[Col. 626]

Thanks to the efforts of the central committee in Kovne, the Lithuanian government finally made the refugees from Suwalk legal immigrants.[13] They were allowed to reside in 16 cities and towns around Kalverie such as: Mariampol, Simne, Pilvishok, Vilkovishk, Lazdey, Alite, Naishtat-Kudirka [Kudirkos Naumiestis] (formerly Vladislavovas) and others. At the conference of Lithuanian rabbis in Kovne, Tevet {5}700 (1940), the rabbi of Suwalk, Rabbi Lifshits, told about the deportation from Suwalk and thanked the country of Lithuania and its President, Antanas Smetona, for allowing the Suwalk refugees to remain in Lithuania.

Very few Suwalk refugees succeeded in emigrating from Lithuania. After all the tortures and suffering they had endured, they were once more captured by the Nazi murderers in their place of refuge – this time, without the slightest chance of escape.

The number of Suwalk Jews in Augustow was larger than in Lithuania – about 4500 souls. This is because Augustow was assigned to the Soviet Union when Hitler and Stalin divided up Poland. The Suwalk Jews remained there; other Jewish refugees from the area joined them later. The Jews of Augustow opened a kitchen

[Col. 627]

For the refugees and Rabbi Zelik Kushelevski, Rinkevitsh and others were mainly concerned with their wellbeing.

The Soviets sent the thousands of Suwalk refugees out of Augustow to the area of Baranovitsh and Slonim where they were later killed along with the Jews of those communities. In the infamous gruesome “Slonim Massacre” they were murdered among others: R'Binyamin Mints and his son-in-law, Shemuel Shapira; R'Naftali Fridlender; Shelomoh Fridlender; Gavriel Smalinski; Yosef Grayever and their families. There were a small number of Suwalk Jews in Lide where Dr. Naftali Staropolski was killed. In Maytshet, R'Hershl Leventin, a devoted worker for the Bikur Holim and Linat HaTsedek was martyred. R'Avigdor Fayans, long-time warden of the Bet HaMidrash HaGadol, brother of the Rabbi of Bialystok, R'David, and the last president of the Suwalk community, R' Yaakov Kusnezitski, died in Grodne.

There was a great Jewish community in Suwalk – and it is gone forever.

[Cols. 627-628]

|

|

| Gravestones overturned by the Nazis, may their names be erased, near the entrance to the Suwalk cemetery |

Translator's Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Suwałki, Poland

Suwałki, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 12 Jan 2022 by LA