|

|

|

[Page 50]

Borukh Szimkowicz

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

Very early Friday, the arrival of the holy Shabbos [Sabbath] already was felt in Klobuck.

Women and girls hurried with cakes and challahs to the bakers. Apple cakes or cakes filled with black berries, which were beloved in Klobuck, were prepared in the houses. They also baked egg cookies that served as a snack at the Shabbos morning kiddush [blessing of wine after prayers]. In addition to the egg cookies being tasty, they also had the virtue that we did not have to wash [and say a prayer, as one does when eating bread] and could eat them right away, as soon as we returned from praying.

The fisherman, Yakl Ripsztajn, stood near the sidewalk near Dovid Zigelman's house with a choice of various sorts of fish: carp, giant perch–pike, bream and other small fish. The fisherman was surrounded by almost all of the women in the shtetl, each wanting to be the first to buy. They shouted, made noise, bargained, but no one went home without a fish. In Klobuck, it could not happen that there was a house that did not have fish for Shabbos.

Friday at around one o'clock, the first Jews were seen going with small packages of underwear to the mikvah [ritual bath]. The first mikvah–goers were: Moshe Dombier, (Zigelbaum), Yehiel Kraszkowski, Dovid Zigelman, Harcka Guterman and Emanuel Wilinger. All of the men of the shtetl went to the bathhouse after them.

When they returned from the mikvah, Shlomo Shamas [assistant to rabbi] already was calling them to the synagogue. He had his well–worn path: from Moshe Szmulewicz to Avrahamtshe Blachacz. At Shlomo Shamas' call, Jews made

[Page 51]

their last purchases in the shops. Zelig, the kerosene maker sold out his last quart of wine, which he carried to the houses. Girls hurried to the bakers with the pots of cholent [stew cooked overnight for eating on Shabbos]. It began to get dark and the holy Shabbos arrived in the shtetl.

Candles lit up the windows in all of the Klobuck Jewish houses. Fathers and children went to pray – in shiblekh [one–room prayer houses] and in the synagogue. We boys were drawn to the synagogue where Moshe Shoykhet already was welcoming the Shabbos. After welcoming Shabbos in the synagogue, kiddish, was made over a glass of wine and we children drank from the glass. The Shamas made sure that every boy received his portion of wine. When a boy drank too much, he never again received a taste of the kiddish.

When we left the synagogue, there already were orkhim [guests invited for Shabbos and holiday meals] waiting, poor Jews, from outside the shtetl, who remained in Klobuck over Shabbos. Almost every head of a household took home a guest.

The Jewish streets emptied very early on Shabbos and the strictly observant Hasidim appeared in silk or velvet robes. They went to the mikvah with slow steps. They went right to the synagogue after the mikvah, said the blessings and took a look at a commentary in a religious text. Of these strictly observant Hasidim I remember the names Reb Josef Buchwajc, Reb Yakov Fishl Rizental, Reb Makhel Dudek, Reb Yeshaya Bachinek, Reb Yitzhak Chada and Reb Itshe Meir Sztiler.

They came to the synagogue to pray very early. However, it lasted until 11 o'clock because they waited for the rabbi to arrive in the synagogue for [the prayer,] Shokhen Ad [He Who abides forever]. And they again waited for the rabbi to end the prayers with the Krias Shema [Shema Yisroel – Here O Israel – declaration of faith] and Shimoneh Esrei [the 18 benedictions].

Shabbos, after prayers, the Klobuck Jews did not rush to eat. Mainly, they did not go around with empty stomachs: they said the blessing on the wine and snacked on eyerkikhl [egg cookies] and they could wait a while. They waited for the cholent [Sabbath stew], which were not given out so quickly by the bakers. All of the wives had to gather in each bakery so that each could identify hers. So that, God forbid, there would not be a mistake.

[Page 52]

The children usually went to the bakers. However, although it was Shabbos, the mothers were not idle. Chopping was heard from all of the houses; with a cleaver they chopped the onions that every Klobuck Jew had to have as a second food after the fish.

They went to sleep for two hours after the midday meal – Shabbos repose. During the summer, after sleeping, they ate Shabbos fruits that had been provided by Yakl the fruit seller. Young people went into his orchard, which Yakl [leased] every summer from the Polish doctor, and ate apples, pears and plums that had been obtained for credit there. Yakl was a pious Jew and understandably did not take any money on Shabbos.

At the same time as the young spent time in Yakl's orchard, several Jews left for the shtiblekh [one room synagogues], for the large synagogue, where they devoted themselves to study. In the summer they studied The Ethics of the Fathers with commentary and Midrash Shmuel [commentary on the Book of Samuel]. In the smaller houses of prayer, the respected members of the middle class – Reb Shmuel Szperling, Reb Ahron Meirs, Reb Meir Szperling and others – took a look at books of ethics: Tiferes Shlomo, Khesed l'Avraham, Kedushat Levi and Avodas Yisroel.

When the evening shadows began to spread over the shtetl, they said the evening prayers in the shtiblekh and in the houses of prayer. The young then would stroll along the roads that led to the surrounding villages. Pious Jews had their roads for strolling – the length of the Shul Gas [Synagogue Street] to the river and large “sidewalk” that connected both corners of the pond.

The preparations for Passover in Klobuck began during Shabbos Shirah.[1] After the prayers on Shabbos Shirah, it was announced in the synagogue that, God willing, everyone should come to the rabbi where the holiday flour would be sold. An auction took place in the rabbi's house. Whoever gave more received the supply contract for flour. A month before Passover, the flour was brought to Klobuck. It was hidden in a special room and the rabbi took the key.

[Page 53]

Two Weeks Before Passover

In the shtetl they began to feel that the great holiday of the Exodus of the Jews from Egypt was approaching – they began to bake matzo. The bakers – my father and Chaim Yehoshaya the bagel maker, Yakl Ribsztajn and Yehezkiel Mejtes, Moshe Mendl and Kopl the baker – were busy making matzo. They heated the ovens at night on Shabbos. After eating on Sunday morning, the rabbi went to look over the ovens to see if they had been properly koshered for Passover.

The rabbi had a system with which to test if the ovens were kosher. He rubbed on the bricks with a long piece of iron and, if sparks spurted, the oven was kosher. However, the rabbi was a sickly man and the iron would fall out of his hands and no sparks were seen. Then the oven would have to be heated again – until the weak hands of the rabbi scraped sparks from the bricks. The rabbi received three or four rubles for his efforts.

The supervisor of the bakeries was Reb Yudl Ahron Gad, a pious, strictly observant Jews and an Aleksander Hasid. He came to examine the utensils that had a connection to the baking of matzo several times a day such as the kneading basins, the water pails, the tables covered in tin, rolling pins and the perforators for the rolled matzos. Pious and healthy “gentile girls” were mostly employed for the rolling. As soon as Reb Yudl entered, the gentile girls immediately moved from the tables. They knew that as long as they stood there, Reb Yudl would not approach the tables. After scraping the rolling pins with glass, Reb Yudl Ahron indicated to the “gentile girls” that they could approach the table.

Water for the matzo bakeries was taken from the river. It was called mayim shelonu waser [water that has remained in a vessel overnight]. Every night in the pre–Passover weeks, they went with water cans and pails to draw water that was carried to the bakeries. There the water was filtered into barrels, covered so that it would cool off until morning so that it was worthy for baking matzos. Every Klobuck Jew felt it was a mitzvah [commandment or religious obligation] to take part in the gathering and carrying water to the matzo bakeries.

[Page 54]

Shmura matzo [matzo made under close religious supervision] was sold by several Jewish Hasidim; Berl Baruch, the supervisor Reb Yudl Ahron and others. There were two kinds of matzo shmura: that which was baked right before Passover and only used on the Seder nights and matzo shmura that the Hasidim ate all through Passover. The Hasidim baked the truly watched matzo shmura on the eve of Passover. The baking itself was a bit of a holiday. Those taking part in the holy service came in holiday clothes. They sang Hallel [songs of praise taken from Psalms] and Hasidic melodies when the matzo was placed in the oven.

Once a case occurred with Reb Berl Baruch that incited the entire shtetl. Reb Berl Baruch hid the shmura flour in the attic so that no one would touch it. Before Passover, when he took down the flour, it was completely wet. It was said cats had searched for a resting place on the flour… The flour was banned and the price of shmura matzo rose terribly in Klobuck.

In the houses of the Klobuck Jews, they began to prepare for Passover at Purim. In addition to scouring, washing, rubbing and scrapping every corner of the house, every woman of the house was busy preparing beet borsht. They purchased herring casks, small and large, several weeks before Passover. They were scrubbed well at the river and then they were left to soak in the water for two weeks. Close to Passover the holiday knife was taken out. The beets were cut and they were stuffed into the casks. The full casks were covered with clean linen and were placed in a corner of the house. The children were told to be sure not to touch the casks and threatened with great punishment from heaven.

Three days before Passover the cask was opened and the borsht was tested; if it poured thickly it was a sign that the borsht was successful.

The “first born sons” ran to the synagogue and houses of prayer on the morning of the eve of Passover to celebrate the completion of the collective reading of the Talmud [commentaries]. The young men of the houses of prayer already were there with copies of the Gemara [Talmudic commentaries] and showed the “first born sons” where to complete the last lines of

[Page 55]

the Tractate [section of the Talmud]. They drank a toast and the young man was redeemed.

After the burning of the hometz [foods not kosher for Passover], they waited impatiently for the sun to set somewhere in the unknown distance and the joyful holiday night would envelope the shtetl.

&nbdp;

Days of Awe, Succos, Hashanah Rabah and Simkhas TorahThe arrival of the Days of Awe already was felt during Rosh Khodesh Elul [the first day of the month of Elul – August or September]. The blowing of the shofar [ram's horn] at the close of prayer reminded the Jews that the Day of Judgment was arriving. Almost every Jew in the houses of prayer studied a page of Gemara because if an illness occurred, a woman had a difficult labor, the shofar could be used to drive away the illness…

Kasriel the bookseller appeared in Klobuck as soon as the first sound of the shofar was heard in the shtetl. He emptied his sack of books near the door of the house of prayer and then arranged them on a long table. He had an assortment: makhzorim [holiday prayer books], sidurim [prayer books], musar–seforim [books of ethics] and storybooks. There were new almanacs with calendars, in which were “prophesies” of when there would be snow, frost, rain and sunshine. The sale of esrogim [citrons used during the Sukkos services B,– Feast of Tabernacles], which were brought to show the rabbi for his appraisal, also began during Rosh Khodesh Elul.

During the days of slikhos [penitential prayers said during the days preceding Rosh Hashanah] the preparations for the “Day of Judgment” increased. A fear descended over the shtetl. Everyone, including women with their small children, came to the first slikhos in the synagogues and houses of prayer at four in the morning. Pious Jews went to the ritual bath before slikhos.

The fruit sellers, who took the fruits to Czenstochow, came to slikhos. Jews from all of the surrounding villages in the Dzialoszyn area came. They filled the prayer houses at the grey dawn and heartrendingly prayed in words not understood by every worshipper.

Everyone entered the synagogue very early on Rosh Hashanah to hear Reb Nota, the shoykhet, recite the verses of the songs of praise; the Jew who prayed at the reader's desk during the morning prayer always was Reb Yeshaya Buchinik,

[Page 56]

until the arrival of Reb Moshe, the shoykhet in Klobuck, who became the usual khazan [cantor].

They went to the river for tashlikh [“casting off” – one's past sins are symbolically “cast off” into a flowing body of water] after the afternoon prayers. Every strata of Jews had its spot at the river: middleclass Jews stood to recite tashlikh across from the synagogue courtyard; Hasidim went farther, where the water was deeper and the currents would carry away the sins more quickly… Radomsker Hasidim had a claim at the river close to the lake. Thus, each Klobuck Jew had his spot at the river in Klobuck and was sure that the river actually removed all of the sins and carried them away to the sea.

Right after Rosh Hashanah, the trade in kapores [chicken used in a ceremony in atonement of one's sins] began. The peasants from the surrounding villages knew what kind of kaporens [fowls] they needed to bring to each house: for a pregnant woman – a chicken and a rooster, for a Hasidic family – white chickens.

At two o'clock in the afternoon Erev [on the eve of] Yom Kippur, the entire shtetl felt itself in a Yom Kippur mood. They went to the afternoon prayers and brought candles with them to the synagogue that were placed in sand boxes. After eating the last meal before the holiday, a cry was heard from each house when the mothers blessed the candles. The children were blessed; best wishes were given to neighbors and the best wishes were accompanied by loud laments.

Everyone went to Kol Nidre [prayer recited on the eve of Yom Kippur]; the large neshome–likht [candle lit in memory of the dead] was left burning and was watched over by an older child. They went to the synagogue, the houses of prayer and the Hasidic shtiblekh wearing kitlen [long white linen robes worn by men on holidays and also used as a shroud] and talisim [prayer shawls], in socks or in slippers, with dread and fear of the Day of Judgment. Here they really cried at the tfile–zake [prayer said on the eve of Yom Kippur]. Then there was a restrained silence.

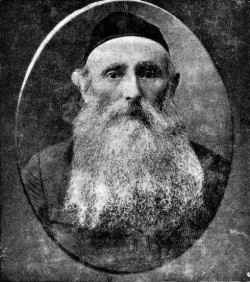

The rabbi and Reb Nota the shoykhet took out the Sefer Torah [Torah scrolls], hugged them to their hearts and, during a procession around the Torah reader's desk, sang in weak, heartfelt God–fearing voices: “Light is sown for the righteous; and for the upright of heart, gladness [Psalm 97:11].” Then came the singing of Kol Nidre by Reb Dovid Hersh[2] the Shoykhet, which infused each worshipper with great respect and a God–fearing shiver.

The day of Yom Kippur passed in Klobuck as in all Jewish shtetlekh at that time. The Jewish streets and alleys were as if everyone

[Page 57]

|

|

| Reb Dovid Hirsh the shoykhet and khazan |

had died. No non–Jews appeared there. The yellow flame of the neshome–likht disturbingly poured out of the windows of every house into the daylight. The heartrending voices of the worshippers, who pleaded with God Almighty for a good year, health and income, drifted from the prayer houses.

After sunset, when the prayers ended, after an entire day of fasting, the pious Jews did not hurry to go home. They remained to recite the blessing for the new moon and again wished each other a good year.

The Jews in Klobuck were already busy preparing for the Sukkos holiday the morning after Yom Kippur. All became master construction craftsmen. They sawed boards, nailed together walls and at almost every Jewish house

[Page 58]

a sukkah [temporary structure in which one has meals and may sleep during the holiday of Sukkos] grew. At the same the trade in esrogim and lulavim [unopened frond of date palm tree – used during prayers on Sukkos], which were brought from Czenstochow, took place.

The eight days of Sukkos passed joyfully with songs of praise that ended with the great joy of the Torah – Simkhas Torah [holiday celebrating the conclusion of the annual cycle of Torah reading and the start of a new one] – the true people's holiday for small and big, for women and men, a people's demonstration with adorned flags, burning candles [in] children's hands in honor of the Torah. These holidays, the Days of Awe and the joyful decorative sukkahs, glowed and lightened the heavy, grey fall and winter that long and painfully spread over Klobuck.

Klobuck Wedding Customs

Every shtetl in Poland had its wedding customs. And the weddings often were transformed into a folk entertainment in which almost half of the shtetl took part. Not everyone was an invited guest, but the majority of Jews in the shtetl celebrated with the families whose children married.

If the groom was from Klobuck, the celebration began with him being called up to the Torah. Relatives and friends of the family were invited to the synagogue early on Shabbos for prayers. The groom was called up to daven maftir [read the last part of the Torah portion and the haftarah – related portion from the books of Prophets]. Reb Dovid Hersh sang a joyful march after the blessings and sugar candies, nuts and raisins were thrown on the groom from the women's section.

When the groom was from another city, they went up to halfway on the road to meet him. For example: the Klobuck in–laws had to meet a groom from Czenstochow halfway on the road in Grabowka. Both families met there; they drank a toast of l'khaim [to life] and everyone joyfully entered Klobuck together. If the groom and his family did not come on time, the in–laws on the bride's side were very insulted and the shame of the insult hovered over the entire wedding. The mothers–in–law particularly felt the hurt.

Klobuck did not have its own klezmorim [traditional east European Jewish musicians]. There were two bands – the Dzialoszyner and Wloyner. The Wloyner were thought

[Page 59]

to be better. Their band consisted of five people. Therefore, they were paid two rubles more. The Dzialoszyner only had four musicians. They were called “di grimplers” [tuneless strummers] in the shtetl. Klobuck also did not have its own badkhen [wedding entertainer or master of ceremonies, who often recited improvised rhymes]. Therefore, they would bring Arye Marszalek or the lame Kopl from Czenstochow.

[They were led] to the khupah [wedding canopy under which the marriage took place], which was placed in the synagogue courtyard, during the dark hours. Candles were placed in the windows on the streets through which the wedding procession passed with music. The entire shtetl almost always stood at the khupah. There was joy and gladness, delight and rejoicing, as is said in the wedding blessing.

Translator's Footnotes:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Klobuck, Poland

Klobuck, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 08 Jul 2014 by JH