|

|

|

[Page 35]

Translated by Sheli Fain

The beginning of the development of the Kishinev Jewish community started around 5510 (1750). This has been a period of flourishing and growth of the Hasidism among the Jewish communities in Eastern Europe. Kishinev was linked to the Jassy (Iaṣi) Rabbinate, which was at the time the centre of Wallachia and Moldavia and was influenced by the Hasidism movement. Hasidism did not encounter any opposition from the Rabbis of the Jewish communities of Southern Russia, Wallachia and Moldavia, including Kishinev.

The Southern Russia Hasidism, as opposed to the North[1] had a strong connection to the Tzadik. The people trusted the Hasidic leaders because they did not force them to study the Torah or the Talmud. At the beginning it found a fertile ground among the young community of Kishinev.

The Kishinev community wished to become spiritually independent from the Jassy (Iaṣi) Rabbinate. In the second half of the eighteen century (about 5640–5690) there were famous Hasidic rabbis at the head of the Kishinev Rabbinate, and thus Kishinev became a centre for the Hasidism followers.

The Kishinev Rabbis

The first Rabbi of Kishinev was Rabbi Zalman, son of Mordechai Shargorodski, a pupil of Baal Shem Tov. He spread the Torah of his teacher and advocated Hasidism to the people of Kishinev, but he did not reach the level of the rabbis who will come after him. After his death (in 5642, 1782), Rabbi Felik, the brother in law of Shmerel Varkhivker, became first Rabbi and after him, Rabbi Issachar, the brother in law of Rabbi Zalman, the first rabbi of Kishinev and chief Rabbi at the Rabbinate.

The fourth rabbi, Rabbi Hayyim Czhernowitzer (Rabbi Hayyim b. Solomon of Czernowitz), was a great Torah scholar and Hasid of his generation and came to Kishinev after he was rabbi in numerous communities in Wallachia and Moldavia. His appointment brought

[Page 36]

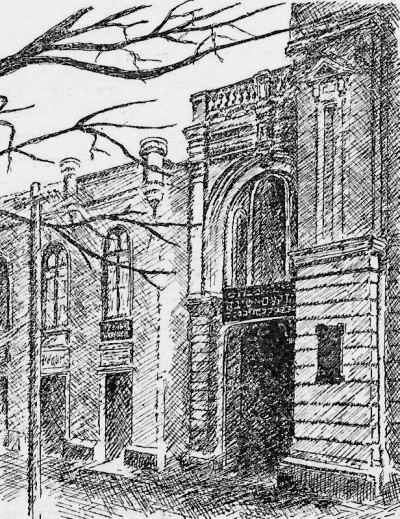

an important change of direction in the life of the Kishinev community. Rabbi Hayyim of Czernowitz did not limit himself to be the preacher and the spiritual leader of the community, but strived to improve and to enlighten the lives of the faithful. He was the first (around 1812, the year of the annexation of Bessarabia to Russia) rabbi to establish community institutions. In 1816 the Great Synagogue foundation stone of was put in place on the banks of the river Byk. This synagogue had 500 seats and was the spiritual centre of the community during tens of years. Other numerous institutions were established around this synagogue in the coming years.

At the initiative of Rabbi Hayyim of Czernowitz, a hospital for the poor was built in the city[2]. Another project was to establish an institution to help the needy. Rabbi Hayyim of Czernowitz was very loved by his Hasidim and he wanted to ensure that they follow the Jewish tradition. He did not like to mix with the rest of the population.[3] During his office, no Jew dared to go against his instructions. He authored many important books on Hasidism and Jewish thought: The Source of the Water of Life (Be'er Mayim Hayyim), A Prayer Book for Shabbat (Siddur shel Shabbat), The Gate of Prayer (Sha'ar Ha'Tefillah). He tried to establish an independent system of Hasidism, and was one of its most faithful teachers. He went to Erez Israel in 1817 (5577) and died in Safed (Tsfat). Long after his death, the elders of Kishinev were still telling stories about his wisdom and his greatness.

After his death they did not choose a new Rabbi immediately. At the intervention of the Rabbi Yehoshuah Heschel from Apta, the Rabbi of Jassy (Iaṣi) and the son in law of Rabbi Hayyim of Czernowitz, Rabbi Aryeh Leibush Melentzhut[4] was named as Rabbi. He was a great Kabbalist and wrote two books “The Wall of Ariel” (Homat Ariel) and “The Bravery of Arieh” (Gvurat Arieh). After his death,

[Page 37]

Rabbi Moshe (Moses Zevi) of Savran was elected. He was considered a great Rabbi of his time and was leader of four communities: Berdichev, Kishinev, Uman and Balta. He visited these communities every month or every other month in order to adjudicate the matters that could not be agreed upon by the locals. He was Rabbi of Kishinev until 1838 (5598). Even though his influence was great in the Jewish community of Kishinev, it could not stop the first signs of Enlightenment (Haskalah).

From the beginning the Enlightenment encountered many obstacles among the Jews of Kishinev, because this young community of the South was a stronghold of the Hasidim. The first signs of Enlightenment appeared as early as the 1830s (5590). The Enlightenment was embraced by the Jews of the South even though they were isolated from the main European ideas developed by Moses (Moshe) Mendelssohn from Berlin.[5]

Many other communities in the South, especially the most developed among them, were not satisfied with the Hasidism and the Jewish community of Kishinev was no exception. The Hasidim ruled the Jewish street, they did not request any intellectual or scholarly efforts and they only asked for a blind trust in the Hasidic rabbi who ruled in the community. It was not difficult to raise the awareness of those who wanted more than blind faith and were searching for more practical knowledge. In the 1830s, when the Russian regime looked for ways to prevent the Jewish “negative influence” over the education of the masses, the Enlightenment found a fertile ground despite the discrimination and the adversity of the Tsarist regime against the Jews. General schools were established in Kishinev, Odessa and Riga to open the window to the big world for the new generation.

Zevi Hirsch Masliansky, the known Zionist advocate and preacher, visited Kishinev in 1891 (5651) and he wrote about this visit:

[Page 38]

“My first sermon I preached in the Great Synagogue was on Shabbat Shuvah and I want to tell the story of this interesting event: the worshipers of this synagogue did not allow anyone to sermonize from the Bimah, a holly place because they said that Rabbi Hayyim of Czernowitz the author of the “Source of the Water of Life” prayed and preached there. They made an exception with me. In the middle of my sermon, there was a great racket in the crowded women section. The noise became bigger and louder. All the efforts to quiet it down did not help. It carried to the men section and I had to step down from the bimah. There were many Hasidim at this event…” (From the writings of Masliansky, vol. 3 chapter 3, New York, 1929 (5689)

Dr. Josef Meisel, the historian of the Enlightenment, mentions that a lot of help was given to the schools of Kishinev by Abraham Stern from Odessa. He hired the first teachers to run the school; among them the poet and mathematician J. Eichenbaum, Dr. Gurvitz and J. Goldenthal (who later became professor at the Vienna University).

The first circle of Kishinev Maskilim (intellectuals) operated next to the school. It was not limited at only teaching the young generation, but tried to influence the entire spiritual aspect of the community of Kishinev. Starting with the 1850s there were many serious confrontations between the Hasidim and the Maskilim (intellectuals). The Kishinev Maskilim (intellectuals) understood that in order to be successful they have to terminate the permanent tenure of the Tzadik, which was a very courageous and revolutionary idea at that time. During this period, Rabbi Israel of Radzyn had great power and influence and many Jews from the towns and villages of Ukraine and Bessarabia revered him. The Russian authorities were afraid of his influence as “King of the Jews” and arrested him. He spent many years in jails in Kremenetz and Kiev. When he was released from jail he decided to settle in Kishinev[6]. He was not allowed here for long and he was forced to flee to Jassy (Iaṣi) and then to Austria, where the Russian authorities did not follow him. After all these wanderings, he settled in Sadigora, where he widened his influence on the Hasidim. After his death, one of his sons wanted to come to Kishinev (1852, 5612). His request was met with great opposition from the Kishinev Maskilim (intellectuals) who considered

[Page 39]

him a threat to the Jewish education[7]. The request of the Rabbi from Sadigora was denied with the help of the authorities. This incident further deepened the conflict between the Hasidim and the Maskilim (intellectuals) and was not forgiven for tens of years after. The ties with the tzadiks of Sadigora became stronger, even though for many years other tzadiks replaced the Sadigora dynasty.

|

|

The conflict between the Meskilim and the Hasidim caused serious problems to the Hasidim of Kishinev. The Hasidim wanted to ensure that the new generation study seriously the Torah and have a strong religious education instead of worshiping the local tzadik. The need to establish Yeshivas in Kishinev, where new generations of scholars will be educated became a new reality. The Yeshiva in Kishinev served the Jews of Kishinev and Bessarabia and also served as the spiritual centre for the Jews of Moldavia, Podolia and the Ukraine. It served as a barrier to the Maskilim ideas that started developing at the time.

The establishment of the Yeshiva in Kishinev in 1860 (5620) marked for the first time in Southern Russia the creation of a spiritual and scholarly centre for the young generation. Hundreds of youngsters (ages 12–19) started seriously studying the Talmud and received a religious Hasidic education. The leaders of the Kishinev Hasidim, Israel David Scheinberg, Moshe Hirsch Halperin, Eliezer Kaushansky, Nakhum Ferfer and others did not hide their worries that the young generation will be lost without a strong religious education. Because it was not easy to find religious educators in Kishinev, the leaders of the Kishinev community search for teachers elsewhere. Rabbi Shabbetai Moshe, a Chabad Hasid was the head of the Yeshiva, after him came Rabbi Abraham Barr, the Hasid from Karlin, a great scholar of the Talmud, who impressed the community with his knowledge. He educated hundreds of youngsters for more than 40 years. The Yeshiva served only as a Torah learning centre in Kishinev and did not grant any diplomas or ordained rabbis and other community leaders, until 1908 (5668) when it moved to the new building.

[Page 41]

The Yeshiva moved in 1900 (5660) to a new location, in the building donated by one of the rich people of the city, Rabbi Shalom Perlmuter, Hassid from Chortkiv, a very active community leader at the time. After the move, a new era opened for the Yeshiva. Shalom Perlmuter wanted to educate suitable candidates for rabbis for the cities and towns of Bessarabia and beyond. Therefore the Yeshiva, named after his death, the Perlmuter Yeshiva, started to ordain rabbis. The scope of the studies became broader and included the Jewish Law. The head of the Yeshiva during this time was Motel Frenkel, the Rabbi of Soroca. He was a great leader and established the Yeshiva reputation as a learning institution.

Later, the head of the Yeshiva was Rabbi Gamliel, the Hasid from Chortkiv, who was famous for his sharpness and accuracy of his judgements. He was well–known for reciting by heart entire chapters from Yoreh De'ah (part of the Shulhan Aruch). Some of his disciples also told stories about his interesting private life.[8]

Although the young generation did not strongly embrace the religious studies, this educational institution helped to preserve the Hasidism and was a special phenomenon in Southern Russia. It played an important role in the religious education of the Jewish youth in Kishinev and gave them an opportunity to broaden their knowledge of Jewish culture and to become leaders in other communities.

Sadly, the historians of the Hassidic movement in Europe did not give a lot of significance to the Kishinev Yeshiva.

We can gather insights on the Jewish society of Kishinev and the beginning of the Haskalah from a number of writings of the time. Abraham Baer Gottlober (ABAG) visited many times Kishinev during 1831–1863 (5591–5623) and wrote a series of articles in the monthly Ha'Magid.[9] About his first visit

[Page 42]

in 1831 he wrote:

“I came here during the month of Shevat, after Passover. I was 20 year old. I heard that Kishinev was a big city with many Jews from all over the country. I found here, like many others, money and gold and my tummy got full of food and I drank a lot of wine. But in this land of flowing wines, to my regret, I did not find what I was looking for. It was not a place of knowledge and brainpower. I found that the local Hasidim were not like the Hasidim in other countries. They were not educated in the Talmud and general topics and did not know “right from left”. They had a blind faith in their Tzadik and did not stray from his teachings…”

In 1840 a general school was founded with the help of Stern from Odessa, but Gotllober considered that some of the teachers were not suitable enough for the task.

“Then, B. Stern, the director of the Odessa school, decided to establish a school for the Jewish children in Kishinev, an important Jewish centre in all Bessarabia. Stern gave Rabbi Moshe Landa the task to supervise the school in Kishinev. Rabbi Moshe Landa, Z”L, lived in Odessa and was a great scholar and a splendid wise man of that time. He was the great grandson and grandson of important rabbis. When I came back to Kishinev after nine years in the month of Shevat 5600 (1840) I hoped to see a school with a scholar and wise man as director and with knowledgeable teachers, but I found that not all glitter is gold. From far it looked like a good school, but when I came close I found a bunch of teachers from all over the country, from Galicia and from Poland, from the North and from the South and they were arguing and quarrelling with one other and they were pulling and pushing in every direction this broken cart, and were disregarding the authority of the director, the wise Rabbi Moshe Landa, making his life bitter and miserable. Landa left his post at the end of 5600 (1840) and he was replaced by Dr. Menakhem Horowitz.”

In 1841, Gottlober came back to Kishinev, this time as an applicant for a teaching position, but he was not hired. He came to Kishinev again in 1863 (5623)

[Page 43]

and he wrote about the school and the Haskalah movement that started to take roots among the Jewish population of Kishinev.

“I am in Kishinev for the last 14 days and I can praise G–D for the changes that took place, that there is a new force that made the smoke of the old chimneys disappear and we can see the stars sparkling in the sky and there is hope that a new dawn will come and bring in a bright sun. It is true that our brothers here are still in the dark and they haven't seen the light of wisdom and do not understand even the learning of the Hasidim. Despite that, I found here wise Maskilim and enlightened people. And I found there a learned man, Rabbi Assaf Horowitz, who came to Kishinev and who was appointed by the government to be the supervisor of the school (first and second class). And I also met there the two sons of my friend, Rabbi Tzwi Rabinovich, Rabbi Aharon and Rabbi Lipa. Both are very nice and ready to educate and improve the level of learning. They know the language and the Hebrew books and Rabbi Lipa is a Hebrew writer and possesses a very fine style and a rich language. All I can wish that there would be more people like them in the community. I also met two professors from the new generation, Dr. Levinsohn and Dr. Kanner, very smart individuals who are concerned with the people's well being. The first is also a teacher of the Ashkenaz language (Yiddish) at the main school. These great people are trying to instruct their brothers and to bring honour to the community. I also met another teacher, Dr. Yosef Blumenfeld, a fine man and a scholar of many languages. He was appointed by the authorities as rabbi of Kishinev and is very involved with the community. Another intelligent and fine man is Rabbi Leon (the son in law of the great late Rabbi Eickenbaum), who served as teacher under the supervision of his late father in law. He had a book store with books in many languages and his home was a meeting place for many Maskilim. Together with Dr. Levinsohn, I have to mention two more teachers the dear Dr. Feivel Khubin and the scholar Muthermeilech and also the Christian supervisor.In this school I also met a first class teacher, Rabbi Meir Kanelsky. He possessed a high knowledge of Hebrew and translated from Russian into Hebrew the book of Osip Rabinovich entitled “Shtrafnoy” Bein Ha'Onashim (In between punishments). This book was also translated into Ashkenaz (Yiddish) by the late Dr. Yast and was published by the printer of the Institute run by Dr. Filipon. He also translated The Legacy of light (Ha'Menorah Ha'Moreshet). He showed me the book “Nathan the Wise” by Lessing, but I did not like the translation, it was probably translated from the French to Ashkenaz and a lot of the poetry and content was lost and became watery.”

[Page 44]

Gottlober praises the government decision to appoint Jewish supervisors for the school:

“The government implemented the decision to appoint Jewish supervisors to all the Jewish schools, supervisors who are familiar with the souls and know how to fight the darkness at the gate, darkness that endangers the people and who know how to deal and remedy the problems that are arising in the community. The schools will become a bright place and the spirit of the community will be healthy.”

He is paying special attention to the question of the education of the girls in Kishinev:

“Our brothers have to remedy now the big gap that exists in the girls' education in a way that is right for the girls and that is equivalent with the rest of the world. In the big cities and even in small towns, the girls are taught Ashkenaz (Yiddish) and French. The Maskilim in Kishinev paid attention to the need to educate the girls and established schools for them under the direction of Rabbi Yacov Shenfeld. The girls are leaning Hebrew and how to pray in Ashkenaz. They also teach the Russian, Ashkenaz and French languages, arithmetic, geography and all the other subjects like in the general schools. The girls learn to sing and dance and other homemaker topics. Three times a week they dance under the instruction of Rabbi Cohen, a Hungarian Jew. These girls are very talented and I hope that the teacher is well rewarded for his efforts. I have to admit that I am a bit disappointed that he chose Shabat for the dance lessons. It would have been better to use the Shabat to read to the girls from the Torah in Ashkenaz translation and to teach them the morals of the Torah stories. I heard that there is another girls' school in Kishinev and I did not meet with the director, but I am sure that he also has the best intentions for the Jewish girls' education.”

Gottlober did not stop with general descriptions of the times, he was also very critical about the fact that the Makilim wanted to look good to the external world, but did not strive to distribute one book written in the spirit of the Haskalah.

“I sold here only 50 copies of my book “Mi–Miẓrayim” (Out of Egypt) and only because my good friend Dr. Joseph Horowitz helped distribute them to his friends, otherwise I would not have sold any. I also visited a very important Kishinev personality and he received me very nicely, but when I offered to sell the book, he said that in his old age he does not have the time to read Hebrew books. I am thinking that he didn't like the price.

I also met in Kishinev one wise and learned Maskil,

[Page 45]

Dr. Azriel Frenkel, may he be blessed and successful in his Torah activities and writings. I was happy to read with him his translation into Askenaz of the Megilat Eichah (The Book of Lamentations). The translation was exquisite and inspired strength and beauty. I can only bless people like Dr. Frenkel”

The conflict between the Hasidim and the Maskilim grew even bigger and stronger in the 1860s. After the government opened two more Jewish schools in 1852, the two camps competed for the control of the education of the young generation. Shlomo Rabinowitz wrote in the journal Ha'Melitz[10] (The Advocate) about the didactic methods of the Hasidim.

“The education system of our brothers lacks the four fundamentals of education: knowledge, respect, rightfulness and productivity. Each youngster from age of three to fourteen is educated by what the teachers know and some are very fine teachers with knowledge and respect; but from age of fourteen when they attend the Beit Ha'Midrash, we see these results – they do not read Hebrew properly and do not understand the meaning of the words, they say the prayers rapidly, go to the mikvah (ritual bath) every morning, wear silk clothes on Shabat and visit their Rabbi once a year. They speak before the elder person does and interrupt their friends, do not ask pertaining questions and do not answer adequately. When they do not hear, they say “I heard” and when they do not know, they say “I know.” They love laziness and do not respect others. They will have lots of sons and daughters – and what will these lazy people do? If they are rich they will be happy, but if poor, they will curse their days. If they are crooked they will cheat, and if they do not have money, they will perhaps become teachers. Why wouldn't their parents send them to the government schools to learn knowledge and respect and not to be like savages in the desert? They might learn ways of how not to live in poverty and to be contributing members in the community”.

The editor of the Ha'Melitz wrote some notes on this article: “you have let your feelings run amok, this will not help them became efficient and knowledgeable”

[Page 46]

Even if the “feelings of the author of the article ran amok” we cannot disregard the fact that the religious schools were neglected and they lacked appropriate teaching methods. Gottlober also wrote in the Ha'Melitz[11] about this situation.

The Kishinev Hasidim did not receive well the criticism, although in their hearts they started to worry about the fate of the young generation. In 1864 a new event added fuel to the conflict between the two groups. A boycott was pronounced against the school opened by I. Zucker in 1861. It was so serious that the government representative, minister Artzimovich had to visit Zucker's school to see how it is run. He found that the school was well run. The Ha'Melitz and the Odesskiy Vestnik (The Odessa Courier) published a series of articles about this event. The editor of Ha'Melitz, Mr. Tzaderboim[12], wrote articles about the danger of a school boycott in Kishinev and the negative effect it will have and he asked the Rabbis of Odessa to arbitrate in this matter. As a result of this publicity, the great rabbis, lead by the famous Rabbi Yechiel Halperin from Odessa announced in the Ha'Melitz 1864, no. 22, that no one, even the great Rabbis, have the authority to declare a boycott without giving serious reasons why, especially when there were no indications of any wrong doing[13].

After a meticulous investigation it was concluded that the boycott was not at all tied to any important leaders of the community and that it was possible that some competitors of I. Zucker started the boycott call[14]. The Jews of Kishinev continued to send their children to Zucker's school which was considered an excellent private school at the time.

We can find satirical descriptions of the different types of Kishinev Jews in the Jewish literature and press of the years 1860–1870 (5620–5630). The Maskilim did not stop at providing new education for the young generation, they also strived to eliminate the negative aspects in the life of the community and to uproot the malicious “two faced concerned” people. Since the teachers of Kishinev did not have the means to publish by themselves, they asked one of the great scholars of the time, Rabbi Yitshak Baer Levinzon (Isaac Baer Levinshon, RIBAL), to write on their behalf and to expose the crooks who tried to take over the Kishinev community. The pamphlet “The Tractate of Him and His Son” (Masekhet oto u'beno) by I.B. Levinzon (RIBAL) made a great impact on the Kishinev community and it was remembered for a long time. The main aim of Rabbi Levinzon's satire was the anonymous liar Kazvi (liar). He wrote in the introduction to the pamphlet:[15]

“Shalom my dear and beloved editor, writers and maskilim, teachers of the respected school in Kishinev, I completed your request in this attached pamphlet in a satirical and spoofy manner…”

In seven paragraphs he describes the character of the liar and phony Kazvi (Liar) who did everything to appear learned and scholarly, when he was a boor and lacked education.

[Page 48]

“He does have some second degree knowledge, and I can tell that he misses Torah and intelligence, because at the beginning of his life he run away from school and did not learn much. He does not know even one single Torah paragraph, does not know grammar and the meaning of the words are a mystery to him. He does not know any foreign language… when he wants to speak these languages even the children make fun of him… this is Him, but he is not ashamed to spread lies all over the country and speak about his phony intelligence and knowledge.”

RIBAL gives us a portrait of Kazvi (Liar) who wanted to be a leader in the community even though he achieved his status and riches by being a crook in business and eliminating anybody in his way.

100 years ago when the Hasidim wanted to be the leaders of the community and until the beginning of the Haskalah movement with its deep moral base – this Anonymous Kazvi appears as a blemish among the young Kishinev community and thus the discontent and the anger against this villain. The Maskilim also wanted to send a signal that not everybody can join their camp unless they posses certain standards such as education and enlightenment and have roots in the community. RIBAL mentions that the community did not like Kazvi's proposal to stop giving alms to the poor on Purim, according to the ancient tradition. Instead Kazvi wanted to buy the hearts of the housewives and for that they denounced and punished him.

RIBAL writes: “the needy were told to continue on the tradition according to the Book of Esther, but they did not go to the house of Kazvi and one of the righteous young people composed on that Purim a nice satire, known as the Purimshpiel in the language of Ashkenaz and all were rejoicing:

|

The good times have ended now I used to hustle and shove the folks While they were eating with a spoon I was gulping with a big scoop

When people used to buy from me |

[Page 49]

|

Now the crowds have dwindled My business is in shambles I am wiped out and broke With a face full of disgrace!

Oy, Purim is already here! |

In this folk song we can see the revolt of the community and the shame of the wicked men who exploit the poor and the helpless.

With the help of the Maskilim actions the revolt that started hundred years ago with the young people of Kishinev succeeded to strengthen the social net of the community. The first Maskilim built the base for a strong and enlightened Jewish community in Kishinev.

The years 1890–1880 are full of important events in the life of the Jewish community of Russia and especially of the one in Kishinev. The Haskalah movement that started in the 1849s in Kishinev and was supported by the Society for Promotion of Jewish Culture (Hevrat Marbei Haskalah beYisrael) founded in St. Petersburg in 1863, diminished its activities. After the Odessa Pogrom, the Maskilim, who thought that through education they will improve the life of the Jews of Russia and get equal rights became disillusioned and started to retreat. In 1871 (5631) after the Odessa Pogrom, the schools of the Maskilim started to weaken[17]. The Jews of Kishinev did not accept well the movement towards assimilation among the Maskilim in Russia. The majority of the Jewish public was spiritually led by the Hasidim and the visits of the Tzadiks. A visit from the Tzadik Rabbi David (Tversky) from Talnoe (Talne, Talna) or another Rabbi was an important event for thousands of Hasidim and strengthened the religiosity of the Kishinev Jews.

[Page 50]

|

|

Kishinev, a city of 40–45 thousand Jews did not have a famous resident Tzadik, but it was a great stop for the Tzadiks, and their visits made a great impression on the locals. The Jews of Kishinev venerated many Tzadik dynasties and were especially under the influence of the Sadigora dynasty, the Tzadiks from Talnoe, Bucha and Skvyra (Skevere). A small group of Chabad rabbis were also active in Kishinev.

[Page 51]

The famous cantor Pini (Pinechas) Minkowsky describes in his memoirs entitled Writings (Reshumot[18]) the status of the Hasidim in Kishinev in the 1880:

“Each Hasidic group had its own leader and “commander in chief.” The Hasidim from Talnoe were led by Rabbi Elisha Halperin. The families of the Tzadik and all the representatives of the Yeshivas who came to Kishinev congregated in his house, where they had many events, festivities and receptions such as the Jewish ritual of Ushpizin, David Meshiah on the eve of Hoshana Rabbah holiday. The Hasidim from Bucha and the ones from Sadigora were led by Rabbi Abramele Grinberg (he was many years the leader of the Society of Hovevei Zion in Odessa). He was a “leader” although he was not a Hassid. He was the son in law of Rabbi Yakov Yosef Artenberg, the pillar of the Hasidim from Bucha and Sadigora. Rabbi Yakov Yosef was a great man and very knowledgeable in Torah and Hasidism and he advanced among the Hasidim with the help of his brother, Rabbi David Artenberg from Berdichev, who was the “Chancellor” of the Sadigora Hasidic court. It also helped that R. Abramele was a very hard working, rich man and owned many large businesses. Rabbi Yakov Yosef was surrounded by Hasidim and Torah and wealth and he was behaving like a king. His Mynian on the “Golden Street” (Harlamphinski Street) was always full with the “who is who” of Hasidim of Bucha. His pockets were full and he was generous because his son in law, Rabbi Abramele, gave him the possibility to be dressed in silk even during the weekdays. He was wearing clean collars every day, his shoes were polished, he had a beautiful face and a trimmed white beard that made him look very noble and gracious. He wasn't very learned, but he always studied the Zohar and Tikunim and he knew how to defend his opinions.”

Minkowsky who was the cantor of Kishinev 1878–1882, describes the spiritual life of his time. He notes that the Hasidim in Kishinev had a very stronghold on the community life. MInkowsky had a lot of opposition from the Hasidim in his youth. Here is what he experienced when he wanted to establish himself as a Cantor at the Choral Synagogue in Kishinev[19].

“The relationship between the Hasidim and I were warm, but in Kishinev, which was the centre of many types of Hasidim, the Hasidim from Talnoe, from Bucha, when I was loved by one group, the other ones hated and persecuted me. And Rabbi Hayyim Velvel, the treasurer, tried his best to starve me.

[Page 52]

In the same period the Maskilim opened a new Talmud Torah that had a big hall where they prayed on the High Holidays and on Shabath. This small congregation was guided by Dr. Levinthal (the son in law of Maximilian Horowitz from Odessa), Abraham Dinin, Shabad, Dr. Bloomenfeld, Josef Rabinowich, who later founded the Mission Synagogue, Rabbi Harik and others. These people asked me to come to sing at their synagogue and offered me a large annual salary of thousands of rubles as opposed to the measly 800 rubles that Hayyim Velvel was so generously paying me. As a business deal, this offer was incredibly good and I would have jumped on the idea and thank G–D that I can get rid of Hayyim Velvel, but on the other hand I loved the Tzadik from Talnoe and my strong ties to the Kishinev Hasidim with whom I celebrated the Ushpizin of Hoshana Rabbah. I also did not want to shame my old father, Rabbi Mordechai Gody, the head of Hashuv'in in Zhytomyr and I feared that hatred will flare up if I change jobs. But when Hayyim Velvel found a better place in the “next world” and I was not under his control anymore, I took the offer of the Maskilim angels. I became their first chief Cantor. After the good news spread over the city, the hate toward me became enormous, especially from the Hasidim of Talnoe who could not bear the shame that I brought upon them, I, who was one of the “jewels” of the city and sang at the table of the great Tzadik.

My sacrifice influenced many in the new generation. Many young people shortened their coats, their beards and sidelocks in order to look like “youngsters” and find a place in the new “city” and their young wives uncovered their heads and bare their hair and came to visit this new “palace” like young ladies going to the theatre. Every Shabath they were flocking to the synagogue to see Pini, the Hassid from Talnoe, dressed in a priest robe, making a spectacle of himself. They also suggested that as Cantor at the Choral Synagogue (Chor Shul) I should not dress like a beggar and I had to shorten my coat and my sidelocks. I was ashamed to cross the town or meet acquaintances on the streets of Kishinev – from all the stores and homes people were coming out to stare and to ridicule me.

In the middle of this crisis, my new dear friend Dr. Levinthal[20] passes away and the leaders of my new

[Page 53]

congregation want me to perform together with other singers at his public funeral in the tradition of Odessa. The entire city screamed at me and shamed me on how do I dare to desecrate the Jewish religion and to conduct his funeral like the “goim” do. “You will not do this mockery in our town” and they threatened me that if I will dare do this funeral, blood will flow from my head. The leaders of my new congregation assured me that nothing bad will happen, because even the Governor will come to this great man funeral. And that's how it was!”

The influence of the Hasidim diminishes in Kishinev the closer we get to the middle of the 1880s. The Haskalah movement is growing and new ideas take root in the life of the community. The “Negev Storm” from Russia in the 1880 causes the Hovevei Zion movement to grow and develop. We also see in Kishinev, as in the rest of Russia the phenomenon of assimilation and a mass departure to America and to Argentina. Many Jews of Kishinev were so disillusioned that they formed a new sect of Jews and Christians, like the group of Joseph Rabinovich “The Children of Israel of the New Testament.”

The 1900s (5660) mark the beginning of the fall of the Hasidism influence in Kishinev which will completely vanish in the next 20 years. The remnants of the Hasidism will be absorbed after the World War I into the organization Agudat Israel, under the guidance of Rabbi I. L. Zirelson (Tsirelson), and a minority of Hasidim will form later the organization “Ha'Mizrahi.”

The 1890s bring a crisis in the Haskalah movement in Russia and a great number of Maskilim started to distance themselves from the Jewish values through assimilation and denial. The majority of Kishinev Maskilim opposed this situation; they wanted education, but they did not want to abandon the Jewish values. This turmoil among the Kishinev Maskilim, like in other large Jewish communities in Russia, caused the creation of the organization The Lovers of Hebrew Language (Hovevei Sefat Ever) . One of the main activists in this social war was the writer Shlomo Dubinsky. He published in the Hebrew press a series of articles and editorials against the sympathizers of assimilation and the Kishinev Maskilim embraced his ideas. Here is a fragment from one of the articles he wrote in the Ha'Melitz:[21]

“There was a time, not so long ago, when we deserted the tradition of Israel. The light that came into the dark homes of Israel in the 1850s and 1860s enlightened us and also confused us. Just like naive children, we believed that by abandoning all that is sacred, all that we cherish and that belongs to Israel, we will be loved by the goim, and that the hate will disappear and we will be “one people dressed the same” … and here came the events of the last years to remind us that we are “the sons of Abraham, Ytzkhak and Yakov”

Dubinsky continues his campaign against assimilation:

“Let's return! To another education! Jewish! History of Israel! Hebrew language! These are[Page 54]

the young voices we hear today from the broken aching souls in this land; although there are still many young people who are deaf to these cries… This is the prophetic dream of our brothers – from the six days of the creation the people of Israel were destined to be like a column of fire and a beacon of light for all humanity…Thinkers, prophets! What does this dream mean to you? The students reject their teachers and do not respect them; for thousands of years we teach the people noble principles, and what is the reward these students get? Blows and tragedy, spiritual wounds and shame! From this day on we should stop being people without answers, but be great and learned”

Dubinsky and the other Maskilim in Kishinev are asking the people not to be stubborn and to reject these old ways. He adds:

“Our bitter enemies want to turn us into savages, without personalities and we should stand strong against these dreadful wishes. Even if they can harm us physically, they can't harm our spirit, because no one can control the spirit. Even if they close the doors of the schools to us, I know that this will not be an obstacle. There were always schools for the people of Israel even when Europe was still a barbaric place. Even now we can establish, with the help of the government, schools where the young ones will drink from the fountain of knowledge and Torah.”

The expectation was that the Jewish people should return to the Jewish sources of knowledge, the wisdom of Israel and give an important role to the study of the Hebrew language. In Kishinev, like in the rest of Russia, the Maskilim started to disseminate the Hebrew language by establishing the “Society of Lovers of Hebrew Language (Hovevei Sefat Ever).”

Shlomo Dubinsky was elated to receive the news. He writes:

“We will teach our sons the Hebrew language and the history of Israel, we will preserve the spirit of Judaism in its purity, our nation will be strong and our language will grow and develop. We should be proud that we are Hebrews! We will be the founders of a new social order!”

The Society of Lovers of Hebrew Language (Hovevei Sefat Ever) played an important role and paved the way to the Zionist movement that started to become a reality among the Jews. It also helped develop the literature in the following years.

The two movements Hasidism and Enlightenment played a major role in the Kishinev Jewish community. Each one in its own way helped to cement the Jewish national character of the community. Both movements left their marks on the life of the community of Kishinev.

Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Chişinău, Moldova

Chişinău, Moldova

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 19 Dec 2016 by LA