[Pages 339-344]

“If There's No Water It's Because The Jews Drank It”

Translated by Judy Grossman

My sister Rivka and I attended a Lithuanian school, and in our home we all knew Lithuanian. I was an able student, and very much wanted to continue with my studies, but the economic situation in our home did not permit me to go and study outside the shtetl.

In Dusiat I was very active in the Hashomer Hatzair branch. At the age of thirteen or fourteen, I was already a counselor. I was in the Tzofim group and was a counselor of the Habirim.

There were three age groups in the “ken” [branch]: the younger ones - “Habirim”; the older ones - “Tzofim”; and the oldest group - “Shomrim”.

I was a very dedicated counselor. I was a bookworm and read whatever came to hand. The teacher Kuzmickas[1], who ran the library in the Lithuanian school, was a member of the Lithuanian Shaulists [Sauliu Sajunga[2]], and I used to receive books in Lithuanian from him; stories with a moral that I used to translate and tell the children in the group.

|

|

| |

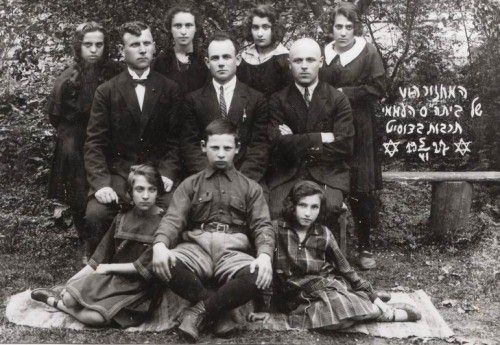

“Tarbut School”, Dusiat, 5 June 1927

Kuzmickas the Lithuanian teacher (left) among the Jewish teachers

Hillel Schwartz (center) and Yehuda Slep, and the pupils

Right to left, standing: Slovka Yoffe, Lana Visakolsky, Breine Shapira, Reinke Levin

Seated: Bunka Chaitowitz, Motale Slep, Nechama Yudelowitz

|

From childhood I loved to hang around the older movement members and listen to their conversations on literature, and I recall the arguments and the literary sentences then, and also afterwards when I grew up. I recall that as a girl I used to join the older members, who used to stand beside the dairy – a two-story brick building – and listen to the music coming from the Lithuanian Gentile's radio. At the time of the processes in Russia, there was already a radio receiver in Ziv's inn, and the thundering voices booming from it reached the street.

In 1935 I went to a movement conference that took place in Kovno [Kaunas] beside the Neiman River [Nemunas], in a pretty place. The conference was interesting, and all in all I felt very good there. From that conference I can recall Wolfke Wilensky, who was an active member of Hashomer Hatzair in Kovno. Wilensky was a commander in the 16th Lithuanian Division during the war, and was worthy the medal Hero of the Soviet Union

When I returned to the shtetl from the conference, I could no longer find a place for myself. The emigration from the shtetl was at its height, with many people moving to Brazil and South Africa, and the shtetl actually began to empty out. The conference opened my eyes, and I became really crazy! The lights of Kovno remained in my mind, and I felt that I could no longer remain in the shtetl.

I should mention that economically we had no future in the shtetl. The Lithuanians didn't prevent us from living the movement life, but all roads were closed to Jewish youth, and it was impossible to obtain positions. The Gentiles also began to take over trade, and it was felt that the Jewish future was fading away. In a home like ours the parents were embarrassed to have their children be simple “tradesmen”. In rebellion against this approach I purposely went to learn to be a seamstress!

Puritans in the Collective in Kovno

I arrived in Kovno with the eight Lit that my sister Chava had given me and joined the Hashomer Hatzair collective. On a regular hachshara [training farm], they worked at ordinary labor, and I worked as a tutor. I was just fifteen years old, and taught a six year-old girl from a rich family. I used to go to their dacha with this family, where they had a summer home and a Lithuanian maid. I also had a student who attended the Hebrew gymnasium [high school], but her parents insisted on speaking Russian with her.

My salary was eighty Lit in addition to room and board and clothes, etc. My salary went to the collective. When we received fifty cents (half a Lit) pocket money from home, a considerable sum, we even went to the opera, sat in the fourth balcony, then returned to the collective and continued singing the arias at the top of our lungs.

The city enchanted us with its sparkling life. When I left Dusiat, it didn't yet have electricity and a radio, whereas in the city the developed technology was a wonder to us. The young people of today take everything for granted, and nothing excites them, whereas we used to be impressed by every innovation. That was a very interesting period.

In the shtetl we absorbed Zionism, which for us was a gateway of hope to get out of the darkness, whereas in Kovno we found other streams, different branches, fashionable clothes, dancing, and we earned money – a different world was revealed to us.

There were rich families there, and we were poor. We were really puritans: no adornments, no salon dancing, only the hora and the hora!

From those days I remember Benyamin Chaitowsky. He was a handsome fellow, and sang like a real singer, and he frequently sang to us. His father, who was a cantor, immigrated to America, and I think that Benyamin didn't join him because of the movement. After the war he became famous as an excellent singer.

Yitzchak Shteinman, who later became my sister Rivka's husband, was also in Kovno at that time. He was a member of the Hashomer Hatzair main leadership council, and I remember his letters to Rivka, which were filled with ideals.

Tamar Teitz was also with us then, the cook in the collective. At that time she was having a romance with Shlomo Goldstein, a member of Hechalutz. They now live in America, and are active in the UJA in Chicago. I met Tamar last year in Kibbutz Afikim, and memories of that time immediately came to mind.

The desire to continue studying didn't leave me, but my main goal was to make aliya to Eretz Yisrael. That was in my blood! However, aliya was a distant dream. They were no longer giving out certificates[3].

We Received a Different Message

In 1939, when the Germans invaded Poland, Polish refugees arrived in Lithuania. Our collective in Kovno was joined by members of Hashomer Hatzair from Warsaw. We were living under the illusion that the Red Army would stop the Germans and that they wouldn't invade Lithuania.

I recall that an escape to Eretz Yisrael was organized then. The gates of Eretz Yisrael were already locked, and the hope of making aliya came to naught. The Jewish youth suffocated from hopelessness and inactivity, especially in the shtetls – where there was no economic future – and even in Kovno you needed influence to get a job.

In 1940, when Lithuania was annexed to the Soviet Union and the communists received legitimacy, it first seemed to us – or at least that's what we, the members of Hashomer Hatzair thought – that things would be good for us, because we had the same ideals. But it didn't take much time for things to change. No more Zionism! We received a different message. Our collective disbanded.

I lived in Kovno with my sister Batya, in a room in the house of a family from Dusiat, across from the Jewish Hospital. Batya worked in Slobodka, and was still a member of collective of “Kibbutz Gesher” [Bridge].

I worked as a cashier – a good job – in the Philips Radio shop, which was a modern shop. I became active in the trade union of the service workers. Like many other young people, I also changed my mind about communism. We thought that it would bring us the new future. We gave up the dream of Eretz Yisrael, and with the characteristic enthusiasm of young people we transferred to communism, but only in the framework of the trade union. We didn't know what was going on in Russia! All doors were opened to us in Kovno. We enjoyed complete autonomy and economic prosperity, but not for long.

| On October 31, 1940, the directorate of the Supreme Council of the Lithuanian Soviet Commonwealth issued an edict on the nationalization of houses. Fourteen thousand residential buildings were nationalized, most of them belonging to Jews[4]. |

I was occupied with the trade union, and because of this activity I didn't find the time to travel to the shtetl. I hadn't seen my father for two years. I remember that at that time I was pursued by this dream, night after night: I came to the shtetl, and my father didn't welcome me warmly, but the opposite, he received me really coldly. I asked him: “Why are you receiving me this way?” I wrote my father about the dream, and poured out my heart to him. He answered me: “Our sages said that a dream is vanity.”

That was the last letter from my father.

| The encounter with the thousands of refugees who fled from the horrors of war was a unique experience for the Jews of Lithuania. The direct encounter between the members of the pioneering movements from Poland and Lithuania was important for both sides.

On the outbreak of war, the Jewish youth in the shtetls of Lithuania were without hope and direction. With the cessation of aliya, many pioneers returned to their shtetls, after a long stay in the hachshara, bringing with them moods of despair and even bitterness and anger against the movement, which had as though led them astray and wasted the beautiful years of their youth.

… The thousands of refugees and the many purchases made by the Soviet army did bring a certain economic wellbeing to Lithuania and caused a rise in business. Nevertheless, it was clear to all that this prosperity was a temporary phenomenon. Many of the members of the wealthy classes lived for the moment. Not a few of the young people began to weave hopes that the Soviet regime in Lithuania would solve their problems. These hopes were also nourished by the fear of Lithuania being occupied by the Germans.

… The refugee pioneers in Lithuania, who were better acquainted with reality, made an effort to stir the young people out of their apathy, and infused their friends and the youngsters in Lithuania with the spirit of the Polish movement: we will be the last ones on the wall [i.e. the last to man the barricades].[5] |

War!

Everything was so sudden! Early in the morning on Sunday, June 22, 1941, Kovno was bombed and the turmoil began. We immediately got in touch with my cousin Noah Poritz, who was in the Netzach collective in Kovno at that time. We felt the need for all of us to be together and we came to his room.

Noah told us that his girlfriend Chaya-Sarah had gone to a rest home in Kolotova (a resort town on the Neiman River) and that he wanted to get to her. He left, and Batya and I returned to our room. In the city, the commotion was at its height. No one knew what was happening. The first bombing was beside the airport, and they were already talking about the first victims. To this day I remember this tragedy with emotion. Until that morning we had lived so tranquilly! On the way back from Noah's room we met Zeldka Charit, and she said that Molotov had spoken on the radio and that everyone was supposed to go back to work.

I don't remember everything that happened on the first day, but we apparently spent the night in our room. In the morning Batya decided to go to work and I remember that I stood on the stairway and shouted to her: “Don't go! Let's go home!” But she went, and we didn't even say goodbye! I never saw her again.

I had made a firm decision: I wasn't going to work. I packed a few of my belongings and went to the train station, which was quite far from there. On the way I went into the room of Chanale Pores, who lived in the new buildings (which the Russians invaded, and left one room for her). I didn't find her and ran to the station. At the gate stood a Lithuanian shouting: “Run, the last car is leaving!” There was no need to ask anything. It was clear that the road led to the east. I got on the train in a panic, with the intention of getting off in Abel [Obeliai], which is about twenty kilometers from Dusiat.

Masses of people were squashed in the cattle train. It was extremely crowded, and everyone pushed each other. I was wearing pretty, light summer clothes, white summer shoes, and the car was filled with tar! A group of underground communist fighters was organizing in the car, and I was taken into this group. We reached Abel and I wanted to get off. There were two girls from Shavli [Siauliai] and a guy from Kovno there, and they stopped me and forced me to remain in the car, because unlike me, they understood what was actually going to happen. Today I think that if Batya had been with me, perhaps things might have happened differently and we would have gotten off. But then I didn't have the time to think. There was no time for soul searching. Everything was so sudden!

We reached the town of Zilupa in Latvia. There they took us off the train and we joined a large group of refugees from Lithuania. There was a railway junction there, and they suddenly began to bomb the train. They evicted us and we moved to another place. We intended to spend the night there, but there was bombing again, with dead and injured, and there I met the couple Reuven Shmit from Ponivezh [Panevesys] and Tzipora Peer from Zarasai, who were already married. They were young, like me, but already looked so worn down! Together we fled to the forest to hide from the bombing. That was the worst bombing I ever experienced!

We were also evicted from there and evacuated on foot to a nearby village, where we stayed for several days. I remember that I was very afraid of the bombing, and kept looking up to the sky. There were Russian villagers there, who suspected that I was a German spy or a Lithuanian fascist, who was signaling the planes. Someone gave me a hint, and I had to leave.

Many people fled towards the Russian border, but the Russians didn't allow us to cross it, because they were suspicious of the people from the Baltic countries and had doubts about their loyalty. In this way we gathered there in groups with no roof over our heads, and with no one organizing anything. But I remember that people helped each other and behaved like human beings. I was dragging a suitcase with me that was a burden, and I kept throwing something out of it. Once I encountered a peasant woman on the way, pointed at the things and indicated that she should take them.

At the end we crossed the border and continued our wanderings. We were a long convoy of refugees and we reached Opochka, a large village in Russia [not far from the Latvian border]. There was a moment when I was overcome by such tiredness that I said: “Darn it, I'm not going on!” Someone passed by me on a motorcycle and pointed at the empty seat, and I rode with him.

Benyamin Chaitowsky was also among the refugees, and he gave a concert and sang for us. If we thought that that town was far from the gunfire, sirens suddenly began to go off during the performance. We were put on the train and continued our travels.

We reached Ivanovo, which is north of Moscow. The journey was filled with tribulations; we were constantly bombed. We kept getting on and off the train.

A month went by until we reached some village and we began working in a kolkhoz [Soviet collective farm]. We worked at harvesting grain and other hard work. It was very hot, and there was no food.

In that place someone told me that he had seen my sister Batya[6], and I requested permission to search for her. There was a center for the registration of refugees in Buguruslan [in the Orenburg Oblast, in the southern Ural Mountains of west-central Russia]. I wrote there to find out about the fate of my loved ones, but they knew nothing about them.

“If There's No Water It's Because the Jews Drank It”

We got onto a large ferry that sailed along the Volga. Whoever could do so got on it. There was no food. All I possessed were a few rubles, my coat and my bag. We reached Stalingrad. I found a beautiful city! I was wearing my summer coat, with a watch on my wrist; I looked like a tourist and people looked at me. You need to know that poverty was already felt there. And we had thought of Russia as the epitome of perfection, that communism had already solved the problem of hunger there! And suddenly, the reality was something else. I didn't know Russian yet, didn't listen to a radio or read a newspaper. Here and there we encountered Jews who spoke Yiddish. I wanted to remain in Stalingrad, which I liked very much, but they didn't allow us to. And we again began wandering.

We sailed along the Volga until Astrakhan, where the river flows into the Caspian Sea. From there, via the main artery of the delta, a distance of a hundred kilometers, we reached Olla, a fishing village. I remained in Olla for about a year. Two others from Lithuania lived there with me, and we met other Jews.

I should mention that at the beginning they related to the Jews with pity, but when the lot of the locals also deteriorated, they began to denigrate the Jews, singing: ”If there's no water in the faucet, it's because the Jews drank it.” As always, when the economic situation is bad, it is the refugees' fault, and especially when they're Jewish.

I was with an acquaintance who was a tailor. He worked and we had bread to eat. There I learned Russian on my own, until I almost forgot Yiddish and Hebrew.

Don't Let Your Spirits Fail!

The well-known Jewish announcer, Yuri Levitan, used to announce the situation at the front on the radio every day. His special and soothing voice accompanied us throughout the war. Later on the Germans contended that they lost the war in Russia because of two Jews: the announcer Levitan, and the writer and military reporter Ilya Ehrenburg. Levitan used to read with pathos, and aroused the listeners to revenge, courage and heroism: “Don't let your spirits fail!” he read, again and again. The information he gave instilled hope, and Ilya Ehrenburg's articles were the same, arousing the soldiers to defeat the fascist enemy.

When the Germans advanced towards Stalingrad, we were afraid that the front was nearing us too, and we decided to leave Olla. We sailed on the Caspian Sea in herring boats. After all, Astrakhan is famous for its excellent fish.

We reached Gureyev, which is in the estuary of the Urals, and there I became ill. I was hospitalized with typhus patients; my body ached and I felt terrible! And what did they give me? Compresses … Later on I learned that it was malaria and I only survived by a miracle. I remember that one time I got out of bed and rushed to leave the room. When they asked me where I was going, I said “to work”. They chuckled. It was ten o'clock at night, and I, who was hallucinating, thought that it was already morning.

We continued on to Karaganda [in Kazakhstan]. This is a region of coalmines, and people of different nationalities were exiled there for forced labor; people who were suspected of treason, among them many of the people of the Caucasus, and also Germans. The supply of coal was essential for the civilian economy and for the war, and after the Germans had already conquered the region of the Donbas coalmines [in the Ukraine], the importance of Karaganda increased greatly.

Most of the male population had been drafted to the front, and many old men worked in the mines under harsh conditions, far away from their homes, and the portion of food they received was minimal. I must state that the situation on the home front was chaotic. In general they didn't worry about civilians, only about the military, but in order to encourage the people to remain in the region of the mines and to prevent depletion of the work force, they saw to a “regular” supply of food. The portion allotted to civilians was four hundred grams, and the coal miners received a “large” portion of eight hundred grams. However, under the difficult work conditions, twelve hours under ground, this portion of food was also not sufficient. Many people broke down from the hard work, and many died of hunger and disease – mainly typhus.

Thanks to influence, I got a job as a waitress in the miners' dining room. I filled a tray in accordance with the vouchers that one of the miners gave me, but famished miners jumped on the tray and gobbled up everything. I didn't know what to do, burst into tears and returned to the kitchen. They put me to work at cleaning.

I was in Karaganda until 1945, and I remember the day the war ended. When we received the news about the victory, everyone was overcome with excitement. Masses of people went out to the streets and began dancing, but the expressions of real joy were still absent, especially as there was no vodka… To this day there are assemblies in Russia on May 9, to celebrate the day the war ended: “the Day of Victory” [День Победы - Den Pabedy].

Return to Lithuania

When Lithuania was liberated, we began to receive the terrible news about what had happened there. I sent a letter to Dusiat, to the Gentile Stalameikis, who had lived there all the years and had been appointed mayor. I asked him about the fate of my loved ones, and he replied that they had all perished, and added that our house was still intact and I could have it.

This was a terrible shock for me. For many days I screamed and cried. One day I asked to go and take revenge! They generally drafted many Jewish boys from Lithuania, but it was hard to get a release from Karaganda, because the place was considered a second front. I was working in the coal miners' restaurant, and they didn't allow me to leave.

Despite the rumors of the annihilation, I still cherished the hope that someone in my family had survived. I wanted to return home. Then I learned that Reuven and Tzipora Shmit were alive. Reuven was working as a senior employee in the Komsomol [Communist Youth Movement]. Zissele, my brother-in law Yitzhak Shteinman's sister, who was in Vilna [Vilnius] then and had already corresponded with my sister Rivka in Kibbutz Ramat Hashofet, managed to locate me and she is the one who arranged for Reuven to request that I go to Lithuania.

Many of the survivors gathered in Vilna, and when I also made my way there, I recall that I felt extremely uneasy. In my memory Vilna was connected to funerals and deep mourning. My uncle Yeshayahu Zilber (whose title was Doctor-Professor) had passed away there in 1940, not long after he managed to leave Berlin. He worked in a teachers' seminar in Vilna, and suddenly came down with some kind of poisoning and passed away. I attended his funeral and his death was a severe shock for us. This was already during the Soviet period. At that time contact was made between the central committees of the Hashomer Hatzair movement in Kovno and Vilna. Our member Yehezkel Levin went to Vilna as a movement emissary, and suddenly passed away there. And again I went to Vilna for the funeral.

I joined the Holocaust survivors. I stayed for a while in the home of Raya and Baruch Krut, and also in the home of my cousin Reizele Shmit. She had spent the war years in Russia. Her father Velvel had also succeeded in escaping from Ponivezh to Russia, whereas her mother Sara had remained in Ponivezh and was murdered by the Nazis in 1941. Reizele passed away in Vilna.

Rachel Rabinowitz (Slovo): Reizele, the granddaughter of the melamed [teacher], Avraham-Moshe Schmidt, was an active communist. At the age of thirteen she had already avidly read “The Communist Manifesto”. When she came on vacation, she used to organize activities with children in the shtetl and put on plays with them. She was arrested by the Lithuanians for the crime of her worldview, and was sentenced to eight years in prison in Ponivezh. Friends freed her from prison and she found a hiding place in the city, but lived in fear of being re-arrested. When Lithuania was annexed to Russia (1940), she received an important position and was the contact person in five languages: Russian, Lithuanian, German, English and French.

Hava Shmit: I remember my aunt Reizel as a very intelligent, kind and extremely generous person, but very sick. It was after the war when she stayed at our house in Vilnius, and my mother [Tzipora-Tzila nee Peer] being a nurse, took care of her. Reizel died in the summer of 1957 and was buried in the Military Cemetery of Vilnius.

I remember my first visit to my shtetl Dusiat after the war. Shmuelke Levitt, Chanale Pores and I together took the train to Abel, from there we reached Dusiat on a sleigh, via the frozen lake, and we stayed at the home of a Lithuanian. At that time, when the Jews began arriving in the shtetls, the Gentiles ambushed them on the roads and shot at them. And truly, I don't understand how we weren't afraid. During this visit we learned the terrible details about the annihilation.

I went into what was once our house. I didn't recognize anything in it. I went inside, and my eyes were filled with tears, and my throat choked up. My tears fell and everything was dark. Every corner reminded me of something. The voices of my beloved family seemed to resound from all sides. I remember that I left the house in retreat.

Time passed, and I decided to again go to the shtetl, after I had heard that you could get money for the property. I came, and the memories again suffocated me. I felt as though I was closed up in a tomb, and I was afraid that I wouldn't be able to get out. They told us that Jewish property was hidden in the Tatars' houses. And in fact, in one of the houses I found our sewing machine, a hand Singer machine. I brought that machine to Israel with me, a memento from home.

Many years had gone by since I went to hachshara. I had left a Jewish shtetl whose language was Hebrew, and every shop in it belonged to Jews. But now nothing remained. The houses – some were destroyed, and the rest had strangers living in them. I didn't see the synagogue, and they told me that it had been turned into a stable.

I looked at the lake, and it no longer seemed so big to me. After all, during my wandering in Russia I had traveled long distances! I had crossed huge rivers and lakes in ferries and boats! We traveled eight thousand kilometers by train from Karaganda, weeks and weeks, so that distances received a new dimension for me.

I stood and recalled our school, the Tarbut School. I recalled the lessons, and remembered the source…

|

|

| |

With People from my Shtetl beside the Monument

[Commemorating 3 Elul 5701 – 26 August 1941]

On the right, standing: Zamke Glezer and Zelig Yoffe; seated in front Ida Yoffe

On the left, standing: Baruch Krut; seated (R-L): Tzila Shub, Luba Napoleon, (-)

|

Footnotes

- During the Soviet period (1940-1941), the teacher Kuzmickas was exiled to Russia [see “In the Lithuanian School”]. Return

- Lithuanian National Sharpshooters Association. At first they comprised paramilitary (civilian fighters) who fought for Lithuanian independence. Over time they become anti-Semitic extremists, and during the Nazi occupation they played an instrumental role in the annihilation of Lithuanian Jewry. Return

- British permit for immigration to Palestine. Return

- Gar, Yosef. Under the Yoke of Soviet Occupation, Yahadut Lita Vol 2, p. 372 Return

- [25] Neshamit-Shner, Sara. Hayu Chalutzim B'Lita, Beit Lohamei Haghetaot and Hakibbutz Hameuhad, 1983. [There were Pioneers in Lithuania. Story of the Movement 1916-1941.] pp. 242-243 Return

- About the bitter fate of Batya Shub see “In the Kovno (Kaunas) Ghetto” and “About Tzirale Kagan and Batya Shub” Return

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Dusetos, Lithuania

Dusetos, Lithuania

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Lance Ackerfeld

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 15 Aug 2009 by LA