|

|

|

[Page 78]

by Y.E.

Translated by Esther Mann Snyder

In the small street of Helping the Old and Alone (Linat Hatzedek) – it was called by this name due to the synagogue that was on that street – the only public educational institution in Brichany stood for more than 100 years. It was established in 1826 and inaugurated by one of the righteous rabbis of that generation, the Admor (Chief Rabbi) R' Yitzhak–Meir. This is known to us from the notebook (pinkas) that was started with the founding of the T”T; by the way this was the only entry in the notebook, noting else was ever recorded. During the following years there occurred changes in the life of the city, but the T”T was not touched, and it remained the same in its content and form just as it was when established.

In the early years of the 20th century about 25 children from poor families studied there and were taught by Yisrael Chak, mainly simple reading and prayer. Just a few reached the level of studying the Bible (Humash). Its existence was based partially on small subsidies from the tax on meat and from The Society for Support of the Poor, and sometimes from occasional donations from a wealthy donor or a small inheritance. The operation of the T”T was given by the Society to Haim Shwartz who devoted himself to the school and was responsible for any shortages; among other things he was able to obtain shoes and clothes for the most needy children.

|

|

[Page 79]

|

|

[Page 80]

I don't know whether it was his own idea or those above him, Haim Shwartz came to the conclusion that it would be worthwhile to introduce some reforms in the school. These included: expanding the curriculum and teaching the children the simple basics of arithmetic and Hebrew language, reading and writing. He asked me, right after Succot 1882, to teach two hours a week in the afternoon, and when I consented he was very happy.

The children were even happier, these forlorn souls, who sat all day for 10 – 11 hours, in both summer and winter, in a small room without light or air, and who learned and knew their whole life just one thing, reading a Hebrew page. They were used to listening to their teacher but never received a smile or a laugh, not a soft caress nor an encouraging word – they accepted everything with indifference, with a sort of doubt and even fear. But, slowly slowly I found a way into their hearts and I was able to talk with them a bit. Then they began to awaken as if a new soul came alive each day and they would wait impatiently for hours and their will to learn strengthened. After a few months we even held a private party on the 15th (”Tu”) of Shvat; the children prepared a program about the holiday with readings and singing, ate the fruits of Eretz Yisrael and their joy was great. Haim Shwartz was very pleased and satisfied and even Yisrael Chak the teacher added his part with the sad news that classes would continue immediately after the party.

The problem of the children bothered me all winter, many of my thoughts were about them – about their bitter destiny and their bleak future and an idea started to grow in my mind. At first, I rejected it because it seemed very daring and not possible to execute. However as much as I deliberated I found it simple and logical – to turn the Talmud Torah into a modern school where the children would be able to receive a full Hebrew education.

I brought up the idea with Haim Shwartz. I was sure he would be enthusiastic however I was startled to hear that my idea shocked him, he looked at me with suspicion as if someone were coming to attack his school and take it out of his hands, and said curtly, “no, the T”T will remain as it is!” He gave no reasons. I later tried several times to persuade him to change his position to no avail. I realized that Shwartz was not the man who was capable of seeing education as a national or human value, and that the institution was more precious to him than the children; he viewed the place as a philanthropic enterprise and I spoke to him no more about it.

Therefore, I brought the suggestion to the two Zionist societies in Brichany, Tzeirei Tzion and the General Zionists. As I expected the proposal was accepted by the Tzeirei Zion; however they opposed the name Talmud Torah as they were worried that the school would be a religious one and they preferred a secular school. The General Zionists also did not reject the plan but hesitated at first because they feared the future financial difficulties that would be revealed when the school was formed and even more by who would own the school. Only after several long meetings and tiring discussions

[Page 81]

|

|

[Page 82]

my proposal was finally accepted in general terms. The General Zionists had a sum of money and a plot of land that were allocated for building the Shaarei Zion synagogue. They agreed to reassign them for a school building on condition that one of the rooms would be designated for their use for the needs of the synagogue. Immediately thereafter a public committee was constituted that included wide ranges of the populace; the committee began to work with much energy and effort.

The cornerstone for the New T”T was laid that summer, on 15th Av. The event was celebrated with much splendor and a great number of residents participated. During the event a large amount of donations was received, amounting to about 130,000 lirot, which strengthened the managers and encouraged them to continue their important work. The Committee sent letters to the Society of Brichany natives in America, and asked for help in constructing the building, naming the sum of five thousand dollars. A response was quickly received from the Society in America saying they welcomed this project and promised to give the sum requested. Just a few days later however, another letter arrived apologizing that they were not able to fulfill the promise at this time because the matter needed to be discussed and clarified. It later became clear that some people in Brichany from the “left” and the committee of the Society for Support of the Poor, and also just miserly mean Jews – opposed the establishment of the New T”T. They wrote letters to the Society in America and to their relatives there that the “Zionisten” (a scornful word) were just interested in themselves and that the new school was just a “bluff” to get money from America to build a Zionist synagogue for themselves, etc. These letters achieved the desired result and the activity in America for the New T”T was ceased before it had even begun.

In order to stop the gossip and to enable the continuation of the construction, which had already begun, a lively exchange of letters was carried on between the Committee in Brichany and the Society in America. It became clear that even in the Society there were people who did not support the idea of a Hebrew Zionistic school, and only after much work and exertion did the Committee in Brichany receive the sum of about $1,800. This sum wasn't adequate to complete the building that was stopped at half of the second floor, whose rooms could be used for the T”T. One room that the synagogue later used was only completed about five years later. The remainder of the rooms was left unfinished for many years.

Even before the completion of part of the building, tiring negotiations began with the committee of the Society for Support of the Poor about moving the old T”T and merging it with the new one. It was suggested that a joint Committee be formed to deal with the school. We were willing to make some compromises both in the administration and also – if there was demand for it – in the curriculum, but they didn't come to hear us, and were totally unwilling to give up the old Talmud Torah. Therefore, after the New T”T was opened

[Page 83]

|

|

[Page 84]

the number of pupils in the old Talmud Torah diminished and continued its miserable existence. It should be noted that after a year the Yiddish school was opened in Brichany, and the Society quickly granted it quite a large sum, although the members of the Society were far removed from Yiddishism or any ideology.

When the time came to open the New Talmud Torah about 150 boys and girls registered among them, about one half were from the weaker families who did not have the wherewithal to pay any tuition. A women's committee was formed headed by Sonia Lerner and Kaila Kilimnik that took on themselves the responsibility to help the poor children. They succeeded in collecting from the residents a commitment for regular annual contributions, and thus the existence of the New T”T was ensured.

Due to their desire that the school be accepted by all levels of society and also because they hadn't given up their hope that the old T”T would finally merge with the new, the school took on a national–traditional character although not really religious. A broad curriculum was designed to include Jewish studies, Hebrew language and literature, Jewish history, etc. The secular studies were arranged according to the curriculum of the state schools. The first teachers were Yaakov Steinhaus (Amitzur), Baruch Yakir, Yosef Hantzis and Michael Cherkis (Amitz). The members of the Supervisory Committee were Izak Ber”g, Arye Bari, Moshe Givalder, Hanina Veiner, Moshe Vizaltir, Josef Feldsher, Yehiel Cherkis, Shalom Kilimnik, Aharon Steinhaus and Yosef–Leib Shiler.

Over the years several attempts were made to merge the two Talmud Torah without success. Both institutions continued to exist until the harsh rule of the Russians.

by M. Amitz

Translated by Esther Mann Snyder

I was one of the first students and a graduate of the first class of the gymnasia that was founded in our town by Roza Solomonovna Diker in 1920.

The opening of the gymnasia was a great stimulus for the broadening of education among the older youth, and was of help to the studious youth who were able to continue their studies without having to travel to other cities. Until then many had to make do with the education they received in the state school managed by Philip Vasilevitz. However it was only an elementary school – five grades with two classes each and only a few places were allocated for Jewish children. Many did not send their children there for fear of desecrating the Sabbath. These parents sent their sons to the private schools of Zusia Lerner and Josef Hanzis, where the curriculum

[Page 85]

was of a lower level. Also the pupils who learned in the Hebrew school, Progymnasia, where the Hebrew studies were an important part of the curriculum, later were not able to continue their studies. Only a very few, the financially well off, went to other cities to study in the gymnasia.

The others needed private teachers however didn't learn much. It was, therefore, a happy event when it was heard that the director of the gymnasia in Hutin was planning to settle in our town and open a general high school.

Accompanied by my father, of blessed memory, my brother and I went to register at the gymnasia, and after a short conversation with Roza Solomonovna we were accepted to the fifth level, which was the highest and would open only if there were sufficient students. After a few days, studies began in a spacious home with a large yard, opposite the home of Abela Broida. Twelve boys and one girl assembled and we inaugurated the new school without any ceremony. Within a short time more students were added and the studies had a routine schedule. After half a year the school was like a regular gymnasia including uniforms – a hat with a wide visor and a coat with shiny buttons – and we were very proud. Since we didn't know Romanian well enough, at first we studied some subjects in Russian, but later on we would study everything in Romanian.

Although the gymnasia was privately run, it still was required to be under the supervision of the Ministry of Education and twice a year the inspectors, who were chosen from among the teachers in the state run gymnasia in Babletzki and Tchernovitz, arrived in Brichany. This aroused in us much excitement, doubts and fears however we felt confident that our gymnasia was on a high level and its diploma would be as acceptable as a state diploma!

As in any school there were dropouts yet despite this the school developed and grew and our class consisted of thirty students. The principal was justly proud of the school she founded and of her students who learned a small amount of Jewish studies and much secular knowledge.

Although the school was Jewish in that its owner and the students were Jewish, there was really almost nothing Jewish about it. As we wrote, a few classes in Hebrew were given that were compulsory, however the Hebrew teacher was not successful in getting the students interested in the subject. The students were indifferent and didn't learn much; in contrast, anyone in the schoolyard during recess could hear all the students speaking Bessarabian Yiddish. Some attempts were made by the teachers to persuade the students to speak Romanian but no pressure was put on them and thus the attempts failed.

Roza Solomonovna Diker (Pinchas) managed the school with authority and built it on a solid base. She was very strict about behavior, order and cleanliness and the studies and routine were properly run. The teachers were also knowledgeable and experienced. We especially liked the teacher Nachum Diker, the principal's cousin, who taught us math and Latin. He knew how to gain the hearts of his students both by his devoted work

[Page 86]

|

|

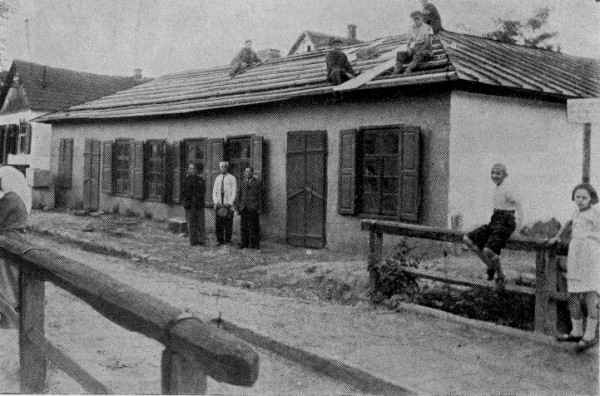

Row 3: Horowitz, Brandes, Zaktzer, Shor, Veiner, Rabinowitz, Gutman, Bukshpon Row 4: (standing) The teacher Grishtzenko, Trachtenbroit, Trachtenberg, Kazhdan, the teacher Diker, Sochotin, Chak, Lerner |

and by his integrity and friendly manner to each of his students. His early demise caused us all much grief. The rules and regulations of the principal were very burdensome and sometimes we rebelled against them.

She was a woman with stubborn goals; she ruled with a heavy hand and strict discipline even though there were students among us who were in their twenties. Once we even declared a strike that lasted three weeks and didn't end until we were promised a change in her attitude towards us. Another time we walked out of our classes and some spoke of leaving the school, which could have endangered the continued existence of our level and perhaps the status of the entire institution. Roza invested much effort to return us to the gymnasia and thanks to her energetic work managed to unite us.

Not only the students rebelled but also the teachers who always feared what would happen when they heard the sound of her footsteps. She exercised her authority also over them and ruled

[Page 87]

without limits and often without restraint… The parents themselves also feared her and stood before her as a slave before his master. Her appearance and tone of voice exuded superiority and arrogance. Her strong character and her ability to impose her will in everything and on everyone certainly were the basis of the gymnasia and its development. There is no doubt that the official supervisors and inspectors were influenced by her personality and that gave us confidence and helped our spirit during the exams. Therefore, the reputation of the school was well known and soon students from other cities began to join the school although a few had high schools in their own towns.

Many of the graduates continued and completed their studies in higher schools in Romania or other places in Europe and returned to Brichany when they had academic degrees such as engineering or medicine, law or agronomy. Many found their place in our town and others found employment in other places.

The onslaught of the war and the Holocaust swept everything away and nothing remains of that institution nor of the many students who learned Torah and secular knowledge there. Roza Solomonovna Diker perished with other holy and pure ones, and she is remembered by the few students who survived the horrors.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Briceni, Moldova

Briceni, Moldova

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 01 Apr 2015 by JH